Part 13: Crusader Kings: Chapter 13 - When the Pope came to Mainz: 1160 - 1169

1160 - 1169: When the Pope came to Mainz

In December of 1159, Duke Aingeru gets a rather unusual new neighbour, as the holy father passes away over christmas, and the Bishop of Mainz is elected pope, bringing the german bishopric into the Papal State.

Though Aingeru's new bride can often be heard complaining about the cold in Germany and making unfavorable comparisons between Wurttemberg and Constantinople, she does what is expected of her, and is soon with child.

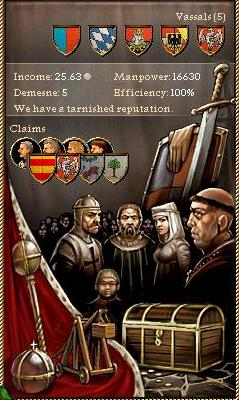

State of the Hohenzollern realm in 1160. Swabia-Baden-Bavaria is among the most propserous realms in Germany, and Aingeru's main concern is where to spend all the money his brilliant steward raises.

1160 is a mostly quiet year, save for the birth of a Hohenzollern daughter in September.

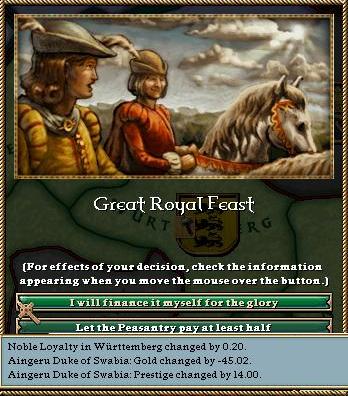

Aingeru holds a grand feast to celebrate the birth of his firstborn.

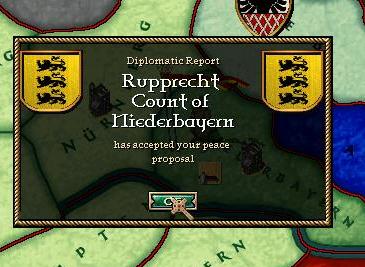

In June the following year, news reach Wurttemberg that the ruler of the only part of Bavaria not under Hohenzollern rule, the Count of Niederbayern, has managed to sevrely offend the new pope and has been excommunicated as a result. The pope has laid interdiction over Niederbayern, and is offering full sanction and forgiveness to any ruler that liberates the land from its heathen count.

Swabia is not slow to respond.

The small army of Niederbayern doesn't even put up a fight, routing simply at the sight of the ten thousand Swabian troops heading their way and soon enough, Niederbayern is added to the Hohenzollern demesne.

To placate his vassals and limit the amount of land that he has to directly supervise, Aingeru entitles a courtier as count of the least prosperous land in his demesne - Baden.

Helene gives Aingeru a son and heir in July of 1162. Perhaps it was the obviously mediterrean tone to the boy's skin, or his large, dark eyes, or the way the infant seemed to shy away from his own father, but those in the room noticed that Aingeru seemed distant and cold towards his eldest-born from the very beginning. He leaves the matter of the boy's name in his wife's hands, and she names him after the Byzantine emperors of past days.

Later the same month, the Count of Alexandria, ruling the ancient city as Aingeru's vassal, begins to crack under the pressure of serving such a distant lord, surrounded on all sides by enemies. Reports from Alexandria become erratic and those that do arrive are filled with endless lists of minor occurances and details, such as the weather on each particular day in the last month, or the amount of mats that were sold in Alexandria's markets on a sunday.

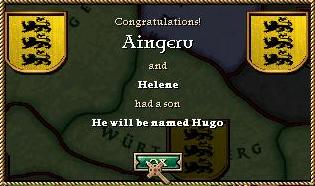

A second son is born in 1164, a blonde little boy which Aingeru seems to take to much easier than with Konstantinos. He names the boy Hugo.

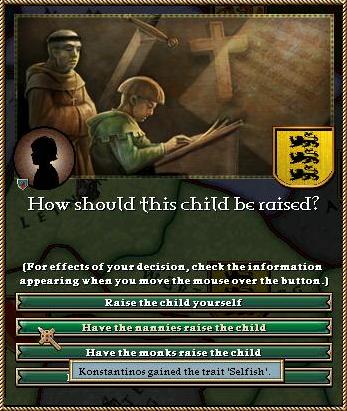

Shortly thereafter, Konstantinos turns two. Instead of taking his heir under his wing and tutoring him personally, as is the Hohenzollern tradition, Aingeru hands him off to the nannies and spends his time doting on infant Hugo.

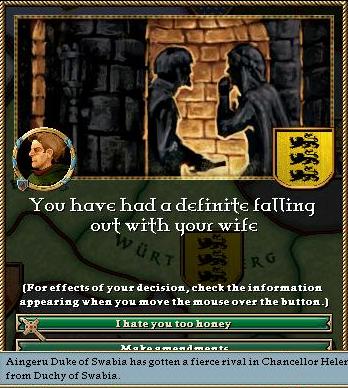

Helena decides to confront him about both the breach of tradition and his general neglect for his eldest-born. The confrontation turns into a ferocious argument, and the ferocious argument results in a bitter falling out.

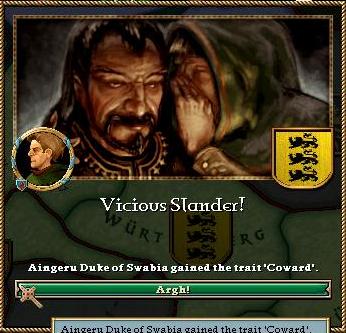

Duchess Helena begins speaking ill of her husband openly, deriding him as a coward who is too content to rest on Swabia's laurels to expand his realm or deal with the problems in Alexandria.

Aingeru, meanwhile, continues to insist on his marital rights, and soon thereafter, Helena is pregnant again.

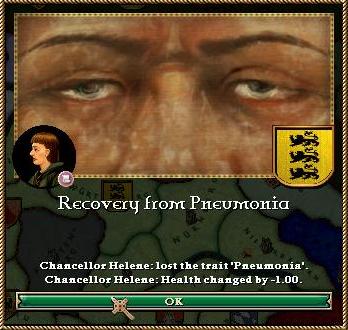

This pregnancy, however, comes with compilacations. Helena falls ill, and despite the best efforts of the healers and their leeches, the sickness worsens into pneumonia, and Helena becomes bed-ridden.

In November of 1165, the pneuomnia claims the unborn Hohenzollern child.

Shortly thereafter, another tragedy strikes as young Hugo is infected by his mother's illness and dies. Aingeru is mad with grief, accusing his wife of intentionally infecting the child to hurt him.

Helena finally recovers from her illness in the spring of the next year, but by now the rift between her and her husband has grown too great to be mended.

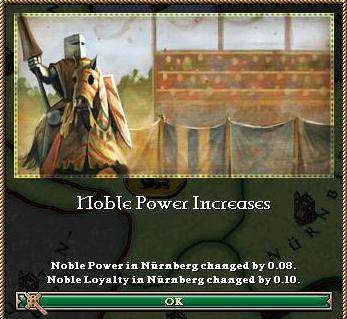

Aingeru spends his days holed up in his chamber and his evenings deep in drink, neglecting his duties as ruler, and his vassals begin to consolidate their power at his expense.

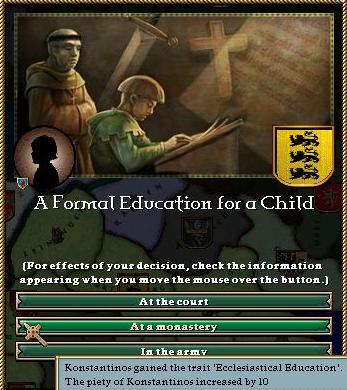

When Konstantinos in 1167 becomes old enough to begin his formal education, he is sent packing to a monastery in Mainz. Helena is forbidden to visit him.

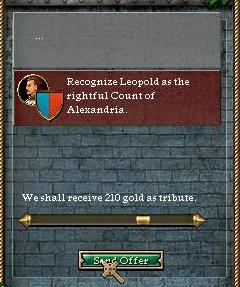

In 1169, the mad count of Alexandria rises against Aingeru.

His advisors insist that he should raise an army and put down the rebellion, lest Swabia lose its foothold in the far east, but Aingeru will have none of it. He brokers peace instead, recognizing Alexandria's independence in exchange for symbolic reparations, a move that greatly damages Hohenzollern prestige.

A few weeks later, Swabia's brilliant and irreplacable steward resigns in disgust over the Alexandrian incident.

Faced with a bitter enemy in his wife, disdain and criticism from his advisors, and hostile neighbours, Aingeru becomes ever more introvert and distraught, even snapping as his beloved daughter.

In April of 1169, believing herself to be acting in the best interests of Swabia and the Hohenzollerns, Spymaster Agaete has her liege killed, and Aingeru joins the long row of Hohenzollern rulers to die before the age of thirty.