Part 102: The Great War, Part 2

Chapter 22 - The Great War, Part 2 - 1917 to 1922Qadis, the capital of Iberia and the Gem of the World, falls to the forces of Almoravid Morocco in the height of the summer of 1917. Berber soldiers stream through the city, fighting for every inch of ground as they secured the outlying bridges, then railway stations, then squares and assemblies and palaces, before finally capturing the citadel and ending the siege.

Qadis isn’t the only city left smouldering in wake of the Great War, however, not by a long shot. Fortresses and cities and towns and villages were burning all across Europe, with millions of conscripts clashing in the hills and mountains of Iberia, forests and swamps of Britain, marsh and rivers of France, plains and lakes of Russia.

Nowhere were the battles bloodier than on the western front, where the promising offensives of 1917 had been ground to a halt, with the fighting devolving into static trench warfare.

Germany’s early victories in France and Occitania were largely reversed by the dying days of September, and after a series of campaigns ended in frustration and catastrophe, the German high command finally turned their attention away from their border with the Dual Monarchy. Instead, they focused their resources on new offensives into Liege and Provence, hoping to bypass the unyielding fortifications in France altogether.

Hundreds of thousands were already dead or dying in the trenches, however, so the bodies for these new offensives had to be rerouted from the eastern front — where the Russian Empire was looming larger than ever.

The battle for dominance in the Vienna Corridor had been inconclusive so far, serving only to exhaust the manpower and resources of both the German and Russian war machines.

Something had to be done about it, so in the summer of 1917, the Russians retreated from the Vienna Corridor and redeployed their armies further north — against Poland. War was declared against the revolutionary government in Poland, and before the year was out, the Russians surging into Germany again.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the Supreme Leader was desperately recruiting another army, defiantly refusing to surrender or concede defeat. And despite the disastrous loss in the battle of Qadis, he was convinced that he had not yet lost this war, not whilst he had vast monetary reserves and thousands of jingoistic revolutionaries to draw from.

And every last coin in the monetary reserve, which had been seized from the monarchist government after the end of the civil war, was concentrated into the heavy industries of Iberia — artillery, mortars, machine guns, airplanes, anything and everything that could bring the Berber advance to a halt.

Supreme Leader Maz Mazin took to the radio near every week, calling on the people of Iberia to take a stand, to rise up against their invaders, to fight for their revolution, and his call was answered in the form of tens of thousands of belligerent youngsters, Andalusi and Portuguese and Castilian and Qattaluni.

By the early days of 1918, Mazin had managed to raise and outfit another army, numbering almost 70,000 soldiers. Still green and inexperienced, they needed to be whetted before facing the French or Berbers, so the Supreme Leader threw them at an expeditionary force that had just landed along the coast of Barshaluna.

The expeditionary force wasn’t large, comprising of 21,000 Scandinavians who were meant to join up with nearby French armies, so the volunteer army was able to take them by surprise and score an impressive victory — 20,000 enemy casualties, at the sacrifice of 6000 revolutionaries.

They would have no time to rest on their laurels, however, with the Supreme Leader immediately ordering a follow-up offensive towards Narbuna, where another 18,000 Scandinavians had besieged the city of Garundah. And again, they were crushed in a bloody battle just outside the city, suffering thousands of casualties to Iberian guns and airplanes.

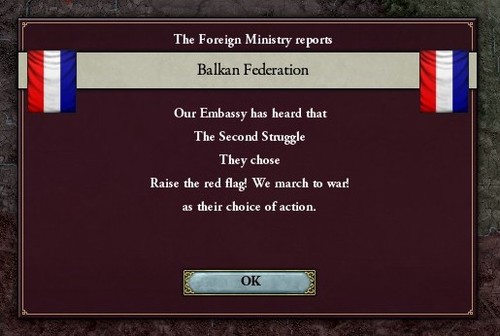

An impressive start to the new year, but the Iberian Union wasn’t the only communist nation embroiled in war, as the Balkan Federation declared the dawn of the “Second Struggle” in spring of 1918.

With the Great Powers entangled in the largest and bloodiest conflict in the history of man, the communist party of Belgrade knew that they would never get a better opportunity to spread their revolution.

And so war was declared on the surrounding countries of Romania, Hungary and the Peloponnese, with the communists vowing to be in Bucharest, Budapest and Patras before the year was out.

The prime ministers and grand viziers of the Congressional Coalition decried this act of aggression, but their response was otherwise tepid, with nobody willing to start yet another war when the world was already aflame.

In Iberia, Maz Mazin didn’t even comment on it, with the Supreme Leader devoting his complete attention to the training and campaigns of his rapidly-growing army, which managed to notch another series of victories throughout 1918, principally against the forces of Provence.

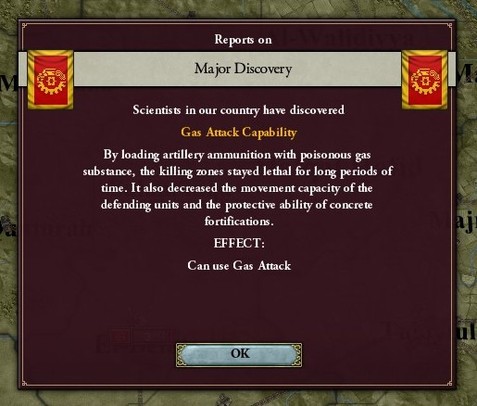

Mazin knew that numbers alone wouldn’t be enough, however. He had marched into the battle of Qadis with superior numbers, only to be utterly annihilated by the superior weapons of war deployed by the enemy.

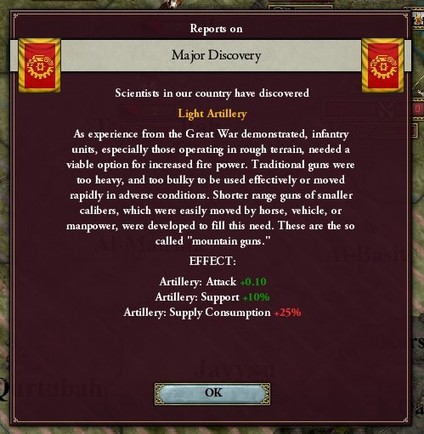

So throughout the summer and winter of 1918, the Supreme Leader supervised the gradual introduction of new technologies and tactics into the Red Army, including poison gas, armoured cars, fighter planes and improved artillery.

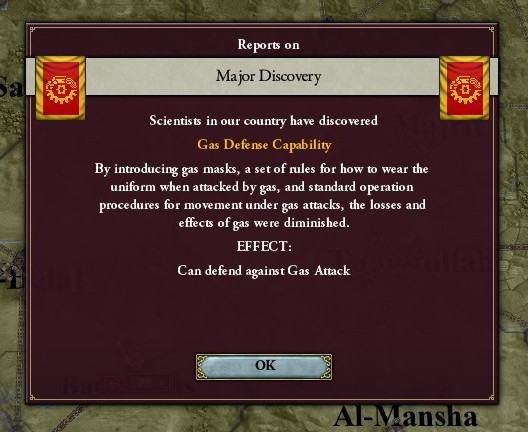

The most important innovation, however, came when German spies smuggled several gas helmets into Iberia, full-face masks that would neutralise the chlorine and phosphene poison attacks that the Berbers favoured so much.

And by December of 1918, the Red Army was finally ready to brawl with the Berbers and French. The two-year build-up peaked with an impressive 85,000 soldiers, mostly consisting of infantry divisions equipped with rifles and gas masks, supported by ever-increasing amounts of heavy artillery and fighter aircraft.

As the Iberians prepare to go on the offensive, however, their descendents across the ocean were firmly forced onto the defensive, driven back by the immense numbers, first-rate weaponry and superior organisation of the New English and French armies.

In the east, things weren’t going much better. Early victories in Tsargrad and Sinai had been quickly reversed by the small but well-trained Egyptian army, and once the Berbers and Russians were able to dispatch their own expeditionary forces, the Armenians and Arabs were quickly driven back into their peninsulas.

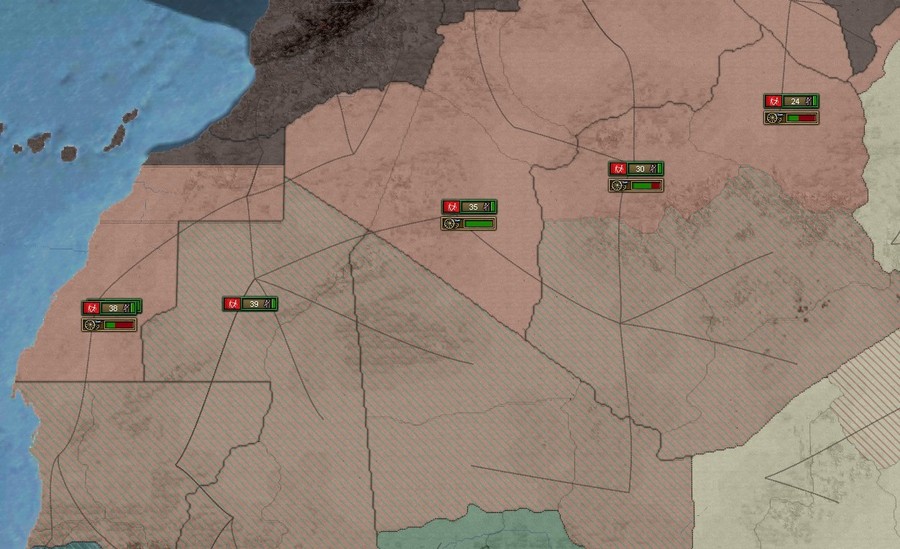

The only glimmer of hope lay in West Africa, where the modernised, professional forces of the Kingdom of Benin had launched a series of sweeping offensives, each more successful than the last. After almost two years of thick fighting in the jungles and deserts of West Africa, the Beninese had managed to occupy Ivory Coast, Ghana, Mali and Jolof, and had even begun pushing into Morocco-proper.

Apparently, the key to these stunning victories lay in Beninese “landships”, armoured machines of immense size and firepower, sheathed in steel and armed with howitzers. These experimental tanks quickly became ineffectual in trench warfare, but they were perfect for the vast, flat deserts that dominated Northwest Africa, allowing the Beninese to overwhelm enemy lines and push northwards in strength.

By April of 1919, the Beninese had captured Ifni and Gouezzem, outlying towns of great strategic value, paving the way to the Isolated City itself — Marrakesh.

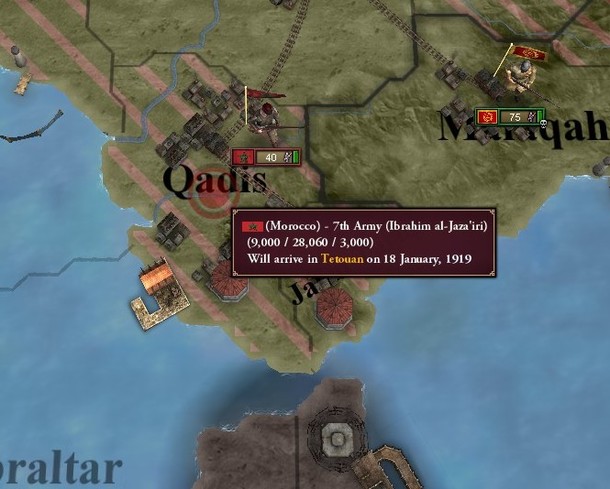

Unsurprisingly, Sultan Ajeddig Almoravid immediately ordered the redeployment of tens of thousands of troops to counter the advance of Benin, withdrawing 20,000… then 55,000… then 60,000… and finally 100,000 soldiers from Iberia.

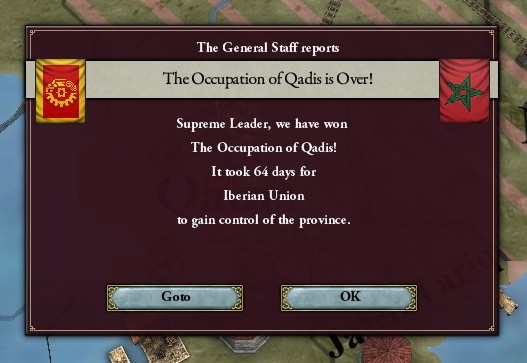

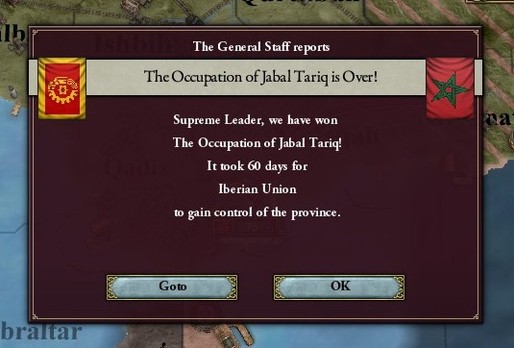

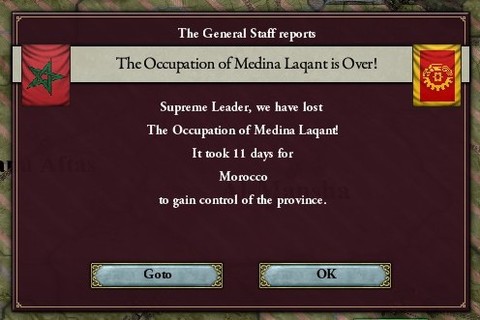

This was the miracle that Maz Mazin had been waiting for — an act of Allah, if he had believed in a god. Without hesitation, the Supreme Leader immediately ordered an advance on Qadis, overwhelming the sparse resistance put up by the smaller Berber garrison.

Qadis was promptly refortified, with Maz Mazin ordering the construction of new trenches, bastions, obstacles and weapons installations around the capital, determined to retain the city at any costs. Let the Berbers come calling again, and they would be left limping and bloodied.

From there, the Supreme Leader ordered his generals to begin a campaign to recapture the rest of Iberia, advancing northwards from Qadis. Algeziras and Wallah were quickly retaken, but there were 35,000 Berbers entrenched around Baja, refusing to retreat or surrender.

This would be the first test for the newly-rebuilt Red Army, with Maz Mazin authorising the attack on the 9th of August. The battle erupted a few days later, and though the fighting would rage for the rest of the year, the Iberians would emerge victorious in decisive fashion.

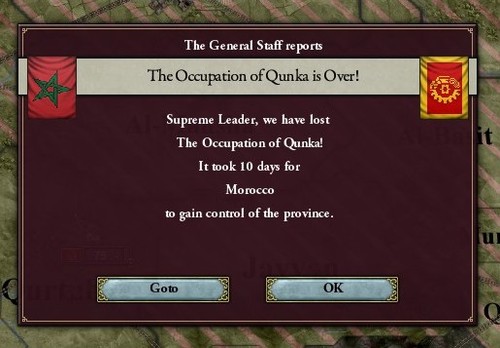

Buoyed by their morale-raising victory, the Red Army immediately pushed towards Qunka on another offensive. Covered by fighter planes and concentrated gunfire, the revolutionaries seized another decisive victory over the Berber garrison, allowing them to retake the city and its environs within the month.

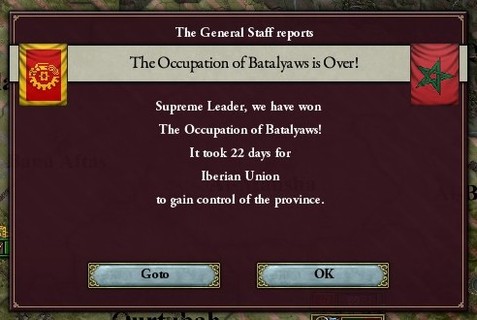

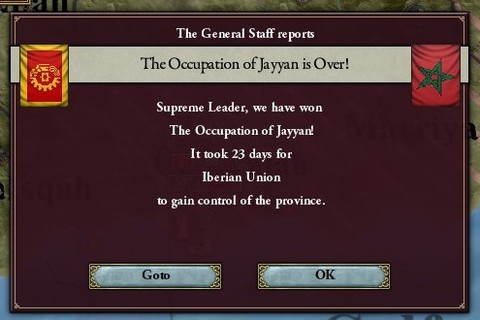

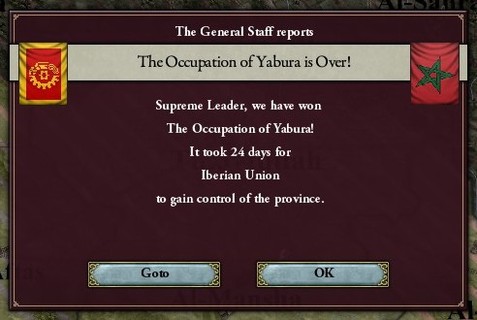

The next year would be spent in furious battle, with Iberian industries churning out aircraft and artillery at an impressive rate, allowing the Red Army to seize the initiative, storm northwards and rapidly push back the Berber lines, liberating Andalusia and Portugal and León-Castille and Qattalun city by city, village by village, town by town.

By the early days of winter, deep into 1920, large parts of southern Iberia had been recaptured by the Red Army — Al Gharb, Qurtubah, Gharnatah, Balansiyyah, Tulaytullah, all densely-populated cities and important industrial centres that were recaptured by the communists by November of that year.

This aggressive drive northwards culminated in the battle of Tirwal, with some 35,000 Berber infantry having retreated into the city after surrendering their hastily-constructed trenches further south.

By the dying days of 1920, the Red Army had swelled to almost 150,000 soldiers, still pitiful in comparison to the French or Russian armies, but certainly enough to squash the last remnants of the Berber invasion of Iberia.

In fact, this was just the latest in a long series of defeats for Almoravid Morocco, who were desperately flailing as a massive offensive was launched in March of 1921, with almost 200,000 Beninese soldiers flooding towards Marrakesh, with the Almoravid capital coming under heavy fire later that year.

To the north, meanwhile, the war in Britain had completely reversed over the past four years. The high command in Paris had deployed another 80,000 French troops to reverse the Celtic offensive of 1917, and by the spring of 1921, they were marching into Scotland and crossing into Ireland.

In central Europe, on the other hand, the static and gruelling trench warfare had seen the Germans, French and Russians throw hundreds of thousands of lives into pointless incursions and futile offensives across the border, all for a few miles of soil and grass that would be lost again a few weeks later.

When the blistering summer heat of 1922 washed across the continent, however, its dry winds brought changing fortunes with them — a joint Moroccan-French-Russian-Provencal invasion from the south, the most ambitious offensive yet, and one that might just break the stalemate in Europe…

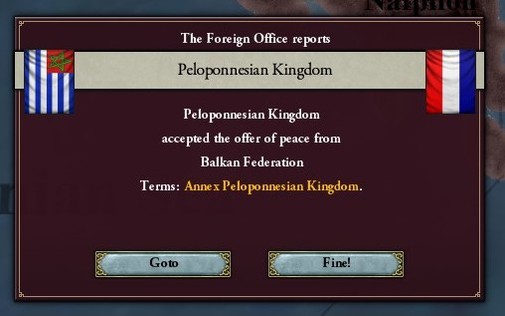

Further south, the Balkan Federation had been conducting a slow but successful invasion into Romania and Greece over the past few years. Their promises of a summer campaign notwithstanding, they did manage to seize Bucharest and Patras by Christmas of 1922.

Once the monarchist governments were overthrown and communist regimes were installed, the Serbians staged plebiscites in both countries with a simple proposal — that they join the Federation of Balkan Socialist Republics, or maintain their independence.

And in what was scarcely a surprise, the electorate in both countries voted overwhelmingly to join the federation, almost suspiciously so.

With that, the Balkan Federation stretched from the beaches of Achaia in the south to the crowded streets of Belgrade in the north, but the Federation was still at war — and this war would prove to be far bloodier. The Romanians and Greeks had been crushed in surprise invasions, but the Hungarians were already fully-mobilised when the Balkans had declared war, making any foray towards Budapest a costly, hellish affair.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, another vicious battle had erupted on the outskirts of Qattalun. This was the domain of Idris Tirruni, the man who had single-handedly sparked the Great War, and Maz Mazin was determined to land a symbolic blow on the enemy war effort by seizing his personal kingdom for the Iberian Union.

Of course, Tirruni wouldn’t surrender without a fight, and convinced the high command in Paris to dispatch 150,000 Frenchmen to secure Qattalun…

The battle of Qattalun would rage for six months, half a year of uninterrupted gunfire, constant shelling, relentless bombardment, futile charges and vicious dogfights and merciless bombing, until at last the French began to give ground and retreat northwards.

A series of ferocious attacks and counter-attacks followed this withdrawal, with the French eventually abandoning almost 100,000 compatriots to litter the trenches and ditches around Qattalun, along with any hope of seizing the peninsula.

From his hidden base of operations, Supreme Leader Maz Mazin ordered his generals to pursue the French, driving them across the mountains and securing the Pyrenaic Wall — those fortifications were essential to the defense of Iberia, and the enemy could not be allowed to keep them.

Whilst the Red Army was retaking the scattered fortresses and citadels and vaults that made up the Pyrenaic Wall, however, another 75,000 Frenchmen crossed the mountains in a ferocious counter-attack.

As the Supreme Leader predicted, however, the impressive fortifications were enough to repel the French assault until reinforcements could pour into the battle, dealing a devastating defeat to the enemy army.

The French were nothing if not tenacious, however, and the next few months would see them launch a flurry of similar attacks all along the Pyrenees — Wasqa, Banbaluna, Narbuna, Garundah — only to repelled with heavy casualties each time.

Whilst the Red Army had been conducting offensives against Berber and French forces, however, malcontents and dissidents across the peninsula were agitating against the communist regime, rising up in rebellions and uprisings for a thousand different reasons — in protest of the war, in defiance of the invaders, in vain attempts to overthrow the government, to name but a few.

So it was deep into 1923, with these constant rebellions and revolts on his mind, that Supreme Leader Maz Mazin reached out to Paris. Both sides had suffered for five long years, and he offered an end to the war, an end to the carnage, an end to the devastation and a return to the status quo.

The French were less amenable, however. Why should they have to accept Iberian terms, when they had already knocked Arabia and Armenia out the war?

Why should they stoop to Iberia’s level, when the immense riches and resources of Central Africa was theirs?

Why should they entertain Iberian diplomats for a moment longer, when they had defeated and occupied the entirety of Ibriz, seizing its prodigious military and industrial arsenals?

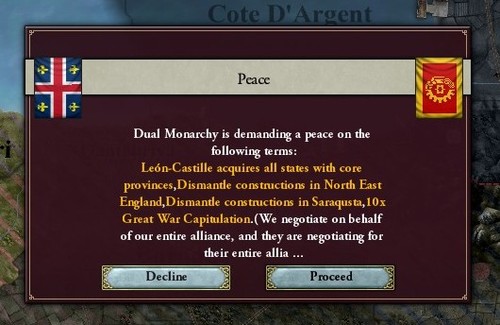

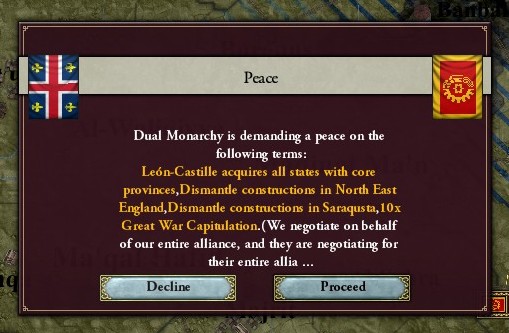

So rather than negotiate, the Dual Monarchy countered with their own unyielding peace terms — the independence of León-Castille and Qattalun, the dismantling of the Pyrenaic Wall, harsh army and navy restrictions, heavy war reparations and complete economic capitulation.

And with that, it became clear that there would be no negotiation or reconciliation. The Great War would be a war of attrition, and it would rage unfettered and undecided until one side had exhausted its resources, collapsed to its aggressors and capitulated to their demands.