Part 103: The Great War, Part 3

Happy new year everyone! Sorry about the erratic upload schedule, it should pick up in a couple weeks after exams are over, but I'll try and keep updating in the meantime.Chapter 23 - The Great War, Part 3 - 1922 to 1923

The Great War has raged for almost five years with no end in sight. Every victory is immediately tempered with another defeat, every breakthrough is quickly undone by another reversal, every advance is inevitably brought to another halt.

Despite the stalemate of trench warfare, by the summer of 1922 it became clear that one side had seized the upper hand — the Constitutional Coalition, led by Russia, Morocco and the Dual Monarchy. Together with their allies and spherelings, the coalition powers had managed to knock Armenia, Arabia, Kongo and Ibriz out of the conflict, appropriating their considerable resources to fuel their own war effort.

But that didn’t mean they’d won the war, not when Beninese tanks were pushing closer to Marrakesh with every passing day…

Not when German troops had managed to parry every Russian and French attack thus far, repelling countless invasions and standing strong throughout the five years of war…

Not when the Iberians had thrown the Berbers and French from their peninsula, retaking lost territories and preparing to launch offensives of their own…

And that’s precisely what they did in the waning days of June, with Maz Mazin — Supreme Leader of the Iberian Union — ordering his generals and marshals to march the Red Army into Occitania, where they managed to decisively defeat a string of French armies in vicious battles below the Pyrenees.

The French quickly cracked under the pressure, and were forced to make a complete withdrawal as thousands began fleeing or deserting in the dead of night, allowing the Iberians to make their first gains of the war — and considerable gains they were, with the Red Army occupying half of Provence within a month, meeting German units just outside the capital of Toulon.

The retreating forces of the Dual Monarchy, meanwhile, withdrew to their core territories in France, fortifying and entrenching themselves along a new frontline just 200 miles from Paris.

Supreme Leader Maz Mazin, coordinating the strategic effort from afar, gave the enemy respite for a few weeks as the Iberians consolidated their captured territories. Both sides massed hundreds of thousands of troops along the frontline, and in October of 1922, the order to advance was finally given.

Vicious battles exploded across the length of France, but the biggest and deadliest would rage around Orléans, as the Iberians and French exchanged bullets and shells and grenades in costly efforts to seize the city. The Red Army held the upper hand from the first days of battle, but the fighting would rage for another month before they managed to seize the city, forcing the French to retreat with heavy casualties.

Almost 50,000 French and Englishmen littered the trenches outside Orléans, and with news of their crushing defeat quickly spreading down the frontlines, the morale and spirit of the French army was shattered. The Iberians pounced on this remarkable collapse of order and discipline, scoring a number of decisive victories and pushing northwards on another dogged offensive.

The Iberian breakthrough and consequent collapse of French ranks also allowed the Germans to seize the upper hand in their battles, with their newly-constructed tanks leading the charge as they made their first advances into French territory, after five years of bloody fighting.

And within weeks, German artillery was bombarding the city of Paris, with the capital of the Dual Monarchy falling on new year’s day of 1923.

This victory didn’t come without cost, however, with the German high command throwing the last of their resources and manpower into the offensive towards Paris. And that, in turn, allowed the Russians to shatter the stalemate in the east and launch a vicious drive towards Hanover.

All of the sudden, the German situation was desperate and unsustainable. A phone call was quickly made to Qadis, with the Chancellor of Germany warning the Supreme Leader that they wouldn’t hold out beyond the winter — not without reinforcements.

Maz Mazin was prompt in his reply, dispatching almost 70,000 soldiers to bolster the German defense at Vienna.

At the same time, however, word reached the Supreme Leader of a distressing upset to the south. The Beninese advance had reached the outskirts of Marrakesh, but they wouldn’t get much further than that, with the Berbers rallying and driving the Beninese back from their capital.

Unless something was done, then the Berbers would counter-attack and reverse all the gains made by the Beninese, making all of their casualties and sacrifices for naught.

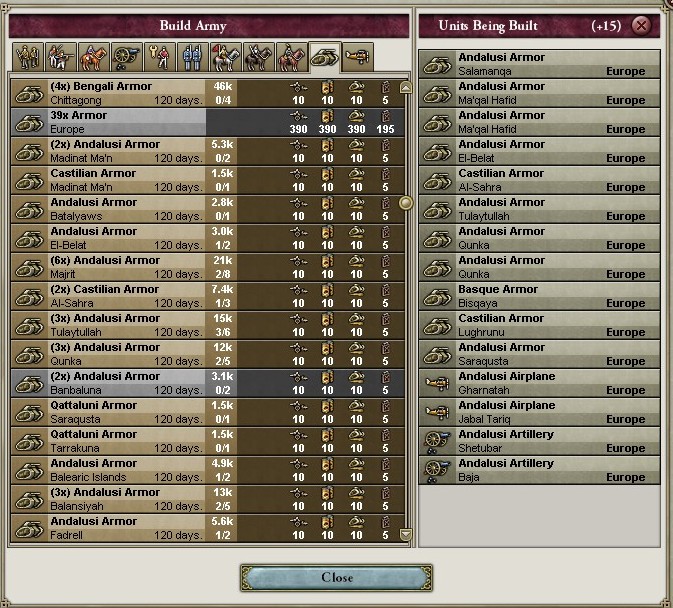

Fortunately, Supreme Leader Mazin had been supervising the recruitment and training of another army over recent months, comprising mostly of conscripted infantry, but with a strong core of artillery and Beninese-style armour.

This army was meant to reinforce the front against Russia, but with the fortunes of war turning against Benin, Maz Mazin decided to dispatch it southwards instead — across the Straits and into Africa.

Back in Europe, meanwhile, the Red Army had reached the eastern front, where the Russians had just launched a concentrated offensive through the Vienna Corridor. The Iberians quickly reinforced the fighting, exchanging bullets with the Russian Army for the first time…

And it was only then that they realised how utterly outclassed they were. The Russian Army was large, mobile, disciplined, well-trained and expertly-led, all of which became abundantly clear when 45,000 Russians clashed with 160,000 Germans and Iberians just outside Bratislava, and somehow emerged triumphant in a landslide victory.

The allied army retreated desperately, withdrawing to the fortified city of Vienna a few miles eastward, where they made another stand against the Russians.

Within days, however, it became clear that they could not be stopped. After suffering a disproportionate number of casualties, the Red Army retreated from the battle, leaving the Germans to be surrounded and crushed in the thick, desperate battles for the streets of Vienna.

And it wouldn’t get much better from there. As the Iberians retreated to friendly territory, the Russians drove into the industrial heartland of Germany, quickly followed by a joint French-Liege counter-attack from the west, and a Provencal-Moroccan invasion from the south.

By spring of 1923, Germany was on her knees.

With their counter-invasion, however, the French had finally exhausted their resources and critically over-extended themselves. Occitania and France were under brutal occupation, famine was rampant throughout the country, and the people were becoming more desperate with every passing day. And still, their leaders were focused entirely on their destructive world-spanning war.

So the people took matters into their own hands.

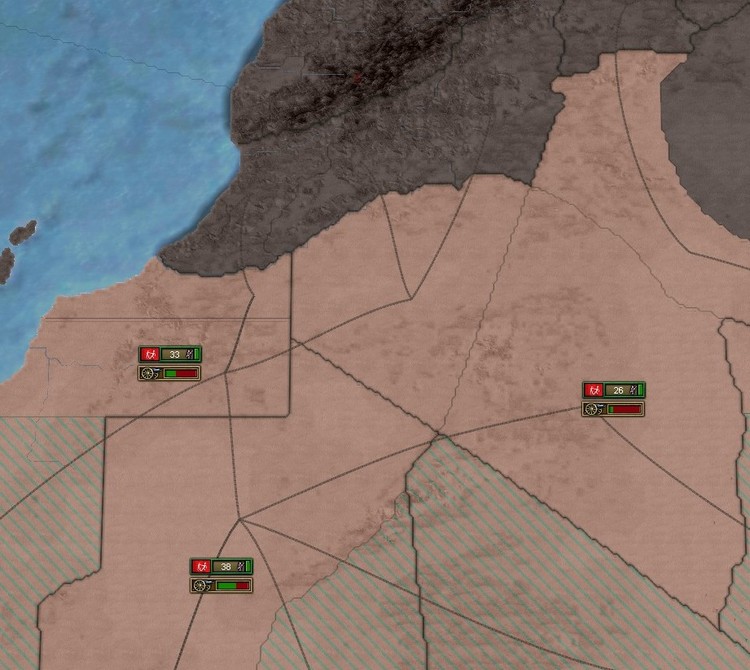

In the south, meanwhile, the Iberian expeditionary force met with early successes in the capture of Tangiers and Ceuta. The revolutionary leadership were determined to relieve their allies in Benin, so this was immediately followed by an offensive towards Fes, but the Berbers brought their advance to a halt long before they reached the city.

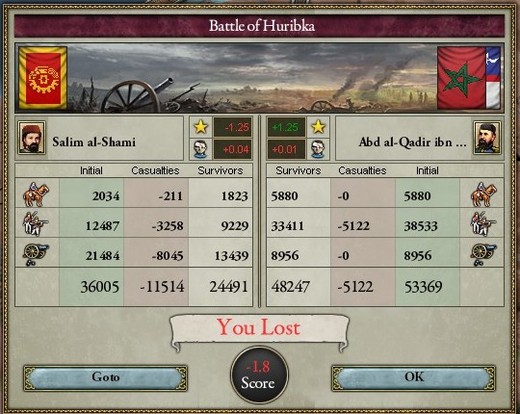

Not far from the town of Huribka, a joint Berber-New English force managed to overwhelm the Iberians in protracted battle, with the fighting stretching on for almost a month before the Iberians finally broke.

The expeditionary force withdrew to Tangiers, and with that, any hopes of aiding their allies were lost. Over the next few months, the Moroccans and Egyptians gradually pushed into the Kingdom of Benin, plundering and pillaging and ravaging as they seized vast tracts of land, a campaign of devastation and destruction that culminated in the brutal capture of Benin City.

Just as the fierce summer of 1923 began, Benin was forced out of the war.

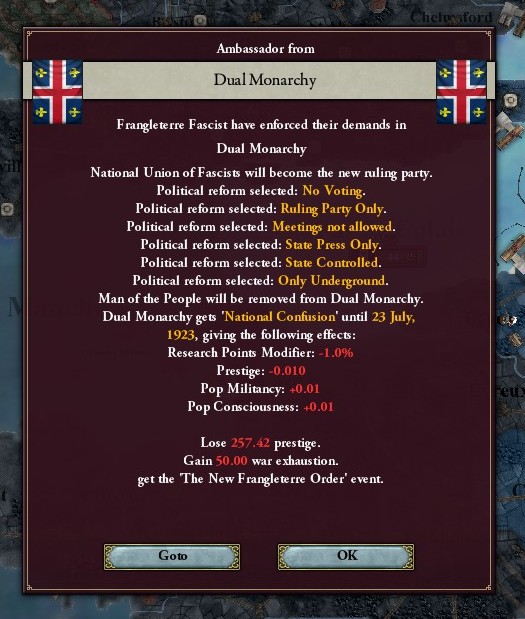

To the north, the chaos and desolation was just as widespread, with millions of commoners rising up throughout France and marching on government offices, lynching state officials and seizing control of their cities. And within mere weeks, hundreds of thousands of workers, labourers, deserters, farmers and soldiers were marching on Paris, determined to set their leaders afire.

Julianna Roman, the elderly Queen of France and England, fled the capital long before they arrived, of course. And as their leadership escaped eastwards and into Russia, the rebels proclaimed the end of the Dual Monarchy, and the dawn of a new order…

The new government immediately shifted their attention to the war, raising and dispatching hundreds of thousands of troops to the frontlines, where they were thrown into battle against the Germans and Iberians.

And in a stunning parallel to the French collapse a few months before, the Iberian ranks cracked, then fractured, then disintegrated in face of the vicious French assaults. A marked collapse in general morale quickly followed, forcing Iberian generals to retreat to the well-fortified line along the Pyrnees, where they urged the Supreme Leader to sue for peace.

At long last, Iberia’s war was over.

The fascists, however, were not so eager for peace. They had seized control of the government on the promise of ending the Great War, but that promise was immediately followed by a string of crushing victories against Germany and Iberia, prompting them to spurn Supreme Leader Mazin’s calls for peace.

Instead, they launched a massive assault on the Pyrenaic Wall, with almost 150,000 soldiers storming the fortresses and citadels that stretched along the mountain range.

The assaults on Wasqa and Bisqaya were repelled easily enough, but the fighting was thickest and bloodiest at Banbaluna, where 80,000 Frenchmen clashed with 10,000 Iberians in one of the war’s costliest battles — for the former, at least. When the first misty morning of August rose above the Pyrenees, they were still manned and defended by the victorious Iberians.

The fascist government sent 150,000 soldiers to march on the Pyrenees, and with 150,000 bodies now littering the mountainslopes, they finally agreed to a ceasefire.

And with that, after exactly six years of war, the guns fall silent.

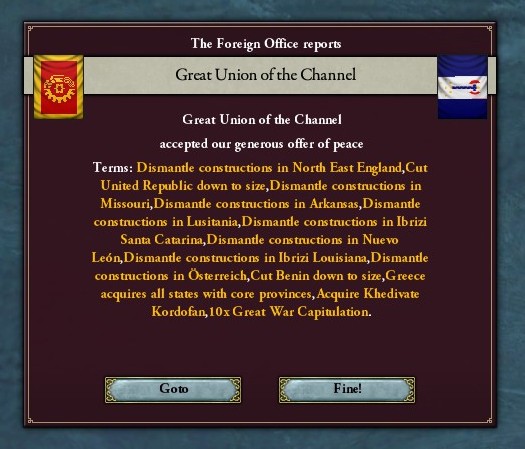

Maz Mazin threw himself into the discussions, and though he managed to negotiate a peace whereby the Iberian Union remained whole, the terms were nonetheless very harsh — the military disarmament of all defeated nations, the payment of immense economic reparations, the dismantling of constructions along the Vienna Corridor and Mississippi River, and the demilitarisation of the Pyrenees.

And that wouldn’t be end of it. The Great War had raged without rest for almost seven years, exhausting the resources and supplies of its combatants, devastating vast stretches of land and destroying nationwide infrastructure, spurring social unrest and political upheaval across the world — and now, the victors would be compensated for their losses.

With the ceasefire in effect and the general terms for peace decided, the victorious powers met in the neutral city of Prague to divide the spoils of war, with the conference opened by Emperor Alexandrovich of Russia. With tensions already rising between the coalition powers, both France and Russia made harsh territorial demands, both seeking to establish themselves as the dominant power in Europe.

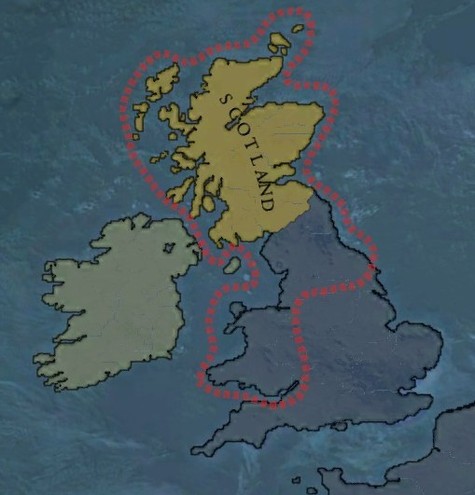

The fascist government in France had agreed to a territorial status quo with Iberia, but they made no such agreement with the United Republic, which was forced to cede Wales and Northern England, and release Scotland as an independent entity.

The Russian Empire, meanwhile, cemented their dominance in Central Europe by annexing the entirety of Poland, releasing Vienna as a free city-state, and forcing Germany to relinquish their Mediterranean ports and Alpine territories.

The Almoravid Sultanate of Morocco, meanwhile, made slightly modester demands. Wary of internal turmoil and the already-tenuous balance of power, they decided to simply seize Timbuktu and Mali from the Kingdom of Benin, finally making their West African territories contiguous with their North African heartland.

As for their colonial demands, the Berbers were much more ruthless, demanding nothing less than the complete cession of Iberia’s colonial empire, whilst the Egyptians were rewarded with control over Kordofan, Darfur and Fashoda.

The maps of the Near East were also redrawn, with the Russians seizing the rest of Yemen and Egypt finally regaining Jerusalem, along with Palestine and Lebanon. The Vali Emirate, which had suffered millions of casualties during the war, were compensated with the emirates of Jordan and Syria.

And finally, in the distant west, New England made no further territorial demands. That didn’t mean Ibriz was left as is, however, they were far too large and threatening, and would always pose a danger to the New English heartland and French colonies in North Gharbia.

So the Revolutionary Republic of Ibriz was castrated, with their entire northern half carved into a puppet state by New England, which dominated every aspect of their new “liberal” government.

Those were the terms for peace. Crippling war reparations, futile disarmament treaties, blatant seizures of land and newly-carved states, the victorious powers have shown little regard for the balance of power or peace in the long term, refusing to find solutions to the questions that precipitated the war in the first place.

There will be a reckoning, of that there is little doubt. The Great War may have ended, but to the horror and dismay of soldiers and politicians across the globe, it would not be the war to end all wars.

Not by a long shot.