Part 104: An Armistice for Ten Years

Chapter 24 - An Armistice for Ten Years - 1923 to 1936In the waning days of the summer of 1923, six years of unrelenting warfare finally came to an end, with the victorious powers of France, Russia and Morocco declaring the immediate cessation of hostilities in the neutral city of Prague. There would be no negotiations or discussions regarding the terms of peace, however. This was a hard-won victory, and the defeated nations would have no voice in the treaty.

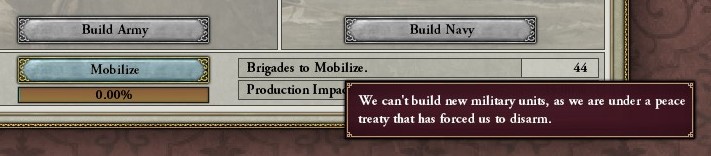

Amongst the many clauses and provisions nestled into the Peace of Prague was the economic capitulation and disarmament of all the defeated nations — Germany, Celtica, Ibriz, Benin, Armenia, Arabia and Iberia. After all the devastation wrought by the Great War, the victors were determined to permanently cripple their longtime enemies.

From the very beginning, however, the Iberians began flouting the terms forced upon them. Supreme Leader Maz Mazin knew that the government in Paris would be itching for another war before long, one that would finally settle the rivalry between France and Iberia, especially now that fascists had seized power.

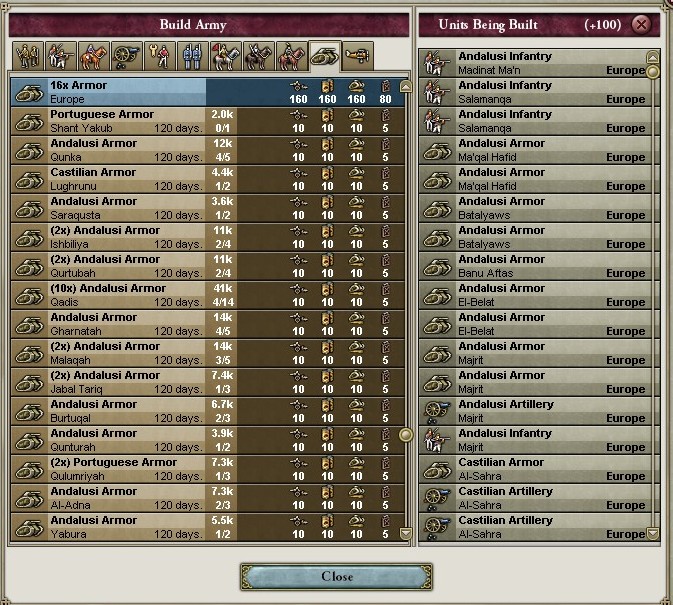

So under the pretext of quashing the ongoing rebellions and riots, Maz Mazin retained the services of some 50,000 veteran soldiers, the well-trained and highly-experienced core of the Red Army.

This defiance was tolerated for the time being, but the same couldn’t be said elsewhere in Europe, even amongst the victorious powers.

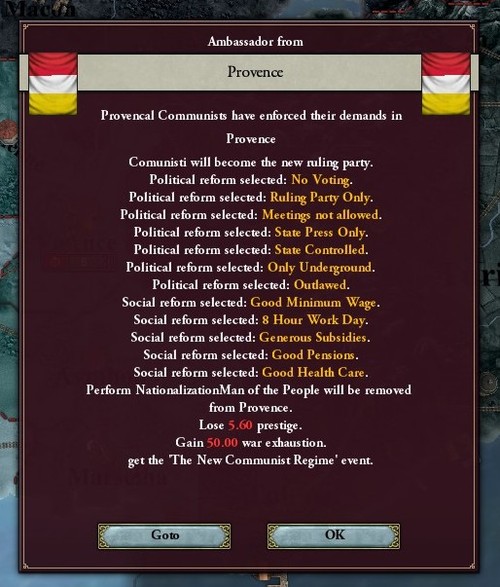

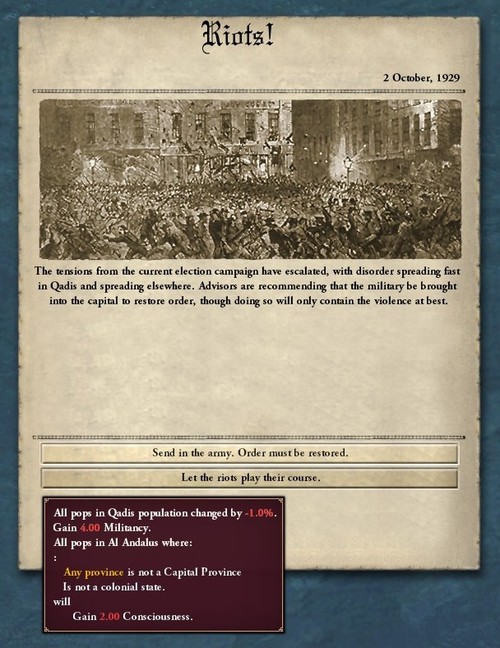

Both Morocco and Russia were tackling nationwide riots and demonstrations, but it was the Republic of Provence who suffered the most. Despite being on the winning side of the war, Provence left to fracture and disintegrate after five years of foreign occupation, with Occitan patriots seizing independence in the west and Italian separatists rising up in the east.

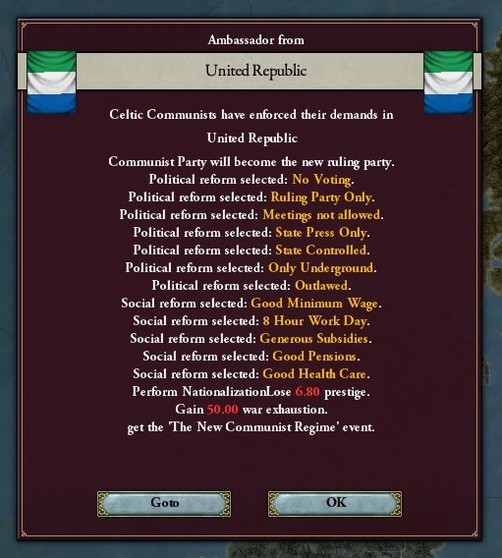

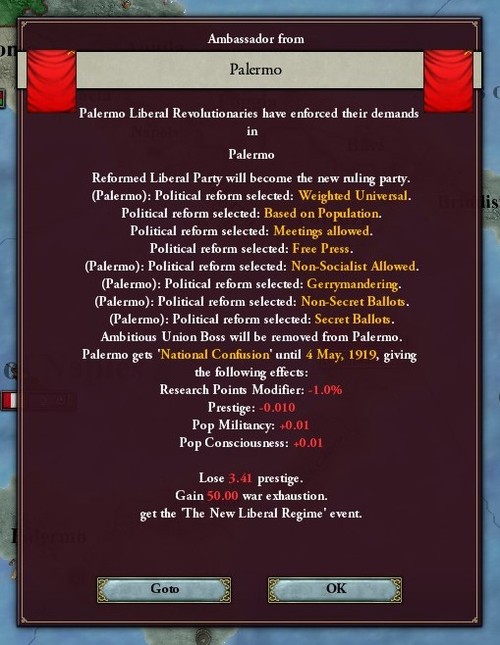

And that wouldn’t be the end of their troubles, because a string of uprisings and revolutions would rock the country over the next few years, mimicking the wave of socialist and liberal discontent that swept across the width of the world in the mid-1920s, especially amongst the defeated and humiliated nations of the Great War, left seething after the harsh terms of Prague.

These newly-revolutionary states were looking towards the two communist behemoths of the continent — the Iberia Union and the Balkan Federation — for support and leadership. Iberia had gained prestige and standing on the world stage after their hard-fought stalemate in the Great War, but the Balkan Federation boasted a much larger and more modern military, one that was even beginning to worry their Russian neighbours to the north.

Thus, determined to become the leading beacon of socialism, Supreme Leader Maz Mazin secretly ordered a military buildup in the dying days of the 1920s, with production focused on the design and manufacture of armour and airplanes.

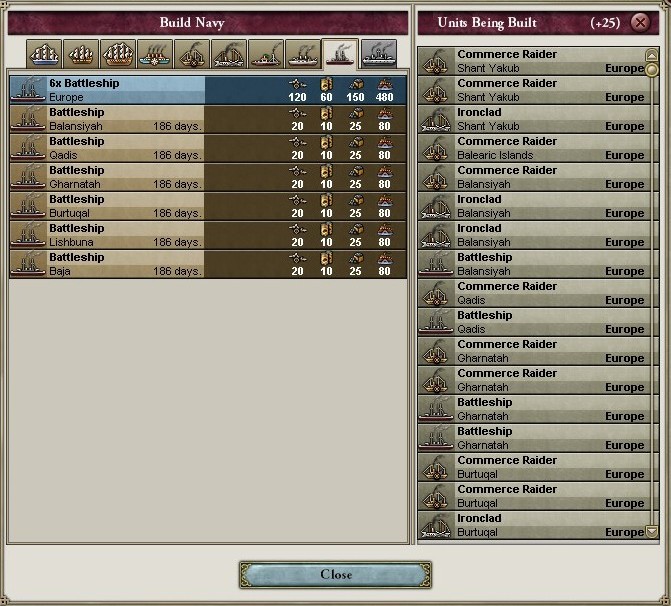

In addition to that, the Supreme Leader began planning for the rearmament and expansion of the Red Navy, which had suffered a string of devastating losses during the war. There would be some investment into battleships, but the high command would prioritise the rapid construction of commerce raiders and submarines in years to come — another covert violation of the Peace of Prague.

Of course, there was another reason for this ambitious rearmament of the military — the persistent threat that lingered to the north, France. Even before the ink had dried on the peace treaties, some 80,000 Frenchmen were stationed on the border along the Pyrenees, to ensure that they remained demilitarised and vulnerable.

And with their rival to the south neutralised for the moment, the French could turn their attentions further afield, towards greater ambitions…

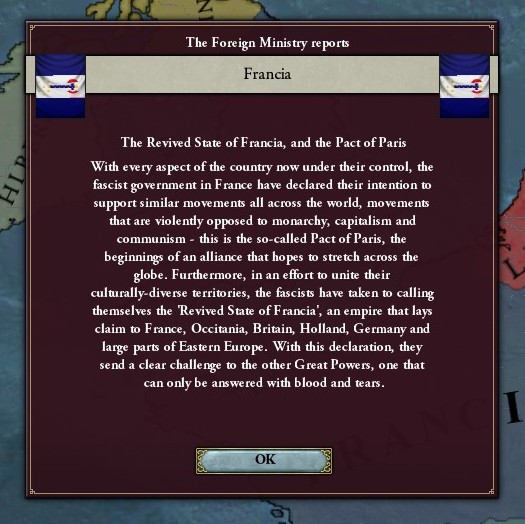

The fascists were led by one Jacques Vernier, a commander in the French Army who was radicalised during the bitter fighting, quickly rose through the ranks of the fascist party, spearheaded their seizure of power, cracked down on civil liberties, executed political enemies, and ultimately declared himself the dictator of the new regime — he was l'Commandant, and his word became law.

And on new year’s day of 1930, almost seven years after marching on Paris, Jacques Vernier made a momentous announcement, with the dictator formally declaring the revival of the “Frankish Realm” — thus severing any remaining ties to the monarchy of France, and harking back to the days when the Franks had reigned supreme over all Europe.

This was a promise to the French people and a challenge to everyone else, so it isn’t surprising that this declaration was met with immediate uproar from many neighbouring countries, but the outpouring of furore only spurred Vernier into further action, with the dictator delivering a series of speeches in which he vowed to support the advance of the fascist movement at any cost.

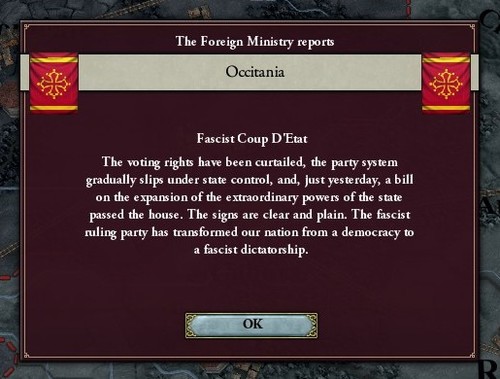

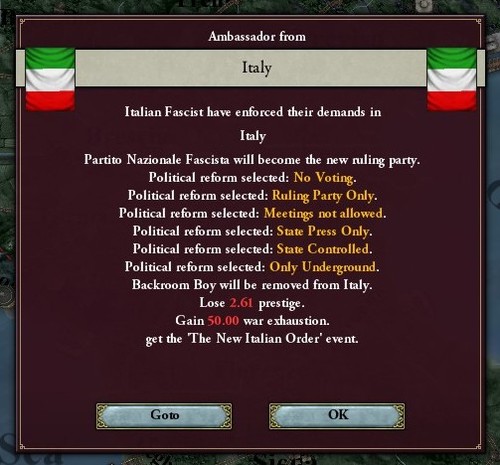

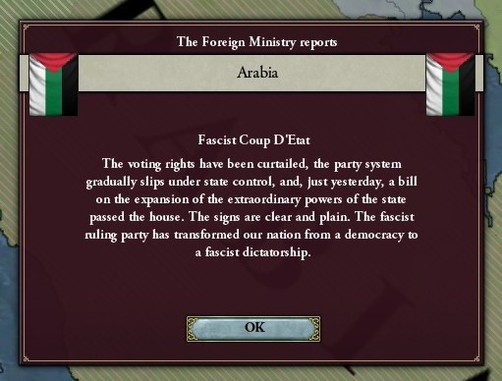

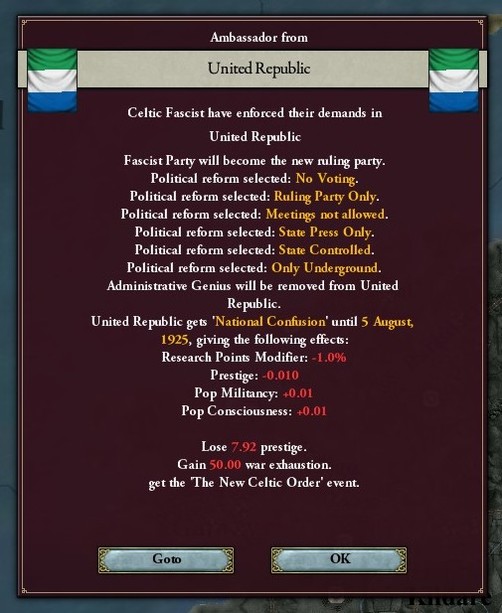

And this “Pact of Paris” would become the foundation of his foreign policy, with a series of coups and takeovers erupting across the continent over the next few years.

Inevitably, however, it wasn’t much longer before the French — or Franks, as they insisted on being called — were butting heads with the other Great Powers.

The Almoravid Sultanate of Morocco had emerged as a victor of the Great War, but paralleling their pyrrhic victory in the Tirruni Wars a century earlier, it had come at the cost of bankruptcy, widespread devastation and rising populism. Nonetheless, Sultan Ajjedig was forced to confront the upstart Franks when they began meddling in Arabia, precipitating a diplomatic crisis between the two allies.

The fascists of Francia, however, were only too willing to sever their relations with Morocco — an empire that was firmly on the decline.

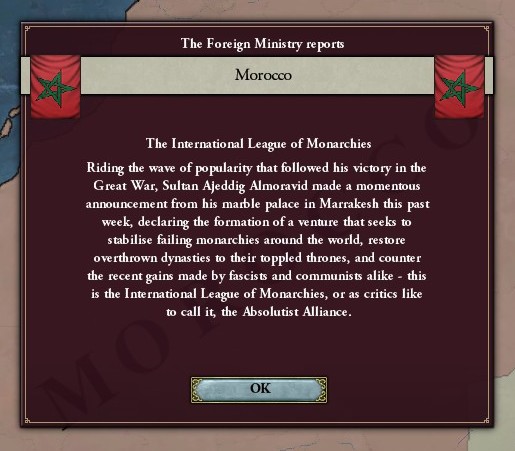

With the Franks refusing to even meet with Moroccan diplomats, tensions began escalating and bubbling into angry outbursts, seething retorts and vengeful promises. As a war scare swept across Europe and North Africa, Sultan Ajjedig declared his intention to counter the radical movement by any means possible, stabilising failing monarchies and restoring toppled dynasties to their thrones — this was the League of Monarchies.

As far as the other Great Powers were concerned, however, this league was simply a futile attempt to stay relevant on the world stage. And with the victors and defeated nations still recovering from the Great War, Morocco’s initiative was met with little enthusiasm, for the moment at least.

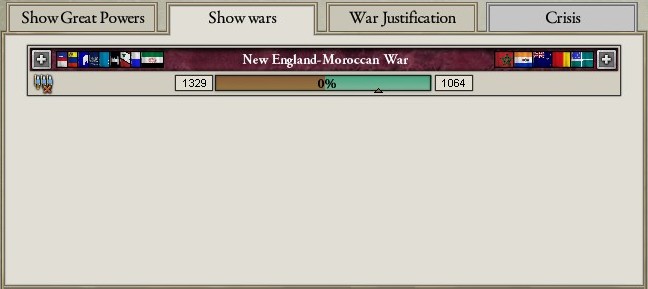

In the new world, on the other hand, New England was enjoying a golden age of economic prosperity and cultural advancements, one of the few nations to prosper after their victory in the Great War. And with Morocco’s prestige and military prowess on the decline, the Richmond parliament began eyeing their possessions in the Caribbean, eventually declaring war on their former allies.

And they wouldn’t be fighting alone, with the Berber Union finally ending their century-long policy of isolation and dispatching a fleet of battleships to secure the waters of the Caribbean, allying with New England in return for territorial promises.

Suddenly faced with the overbearing might of the Gharbian powerhouses, the Almoravid Sultan turned to the only ally left to him — Russia.

Emperor Alexandrovich immediately refused his call to arms, however. The Russians were determined to oppose the advance of Fascist Francia in Europe, and had no interest in being dragged into a globe-spanning conflict over Morocco’s scattered colonies.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the years that followed the Peace of Prague finally allowed the communists to secure their revolution, with Maz Mazin gradually rooting out and crushing the last of the liberal, monarchist and fascist resistance to his rule.

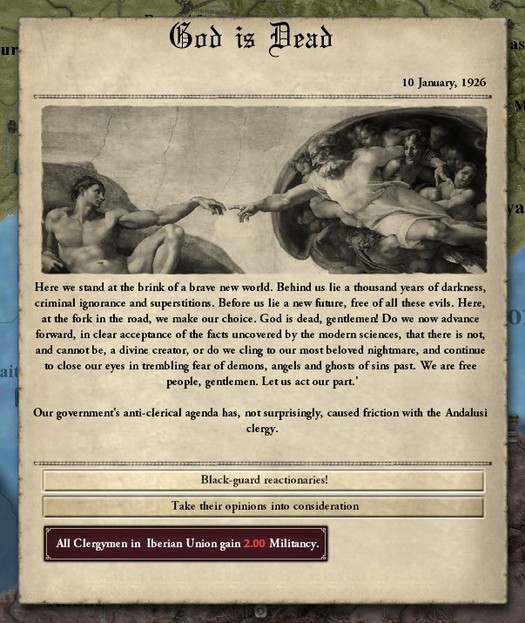

And with that, he could begin implementing the policies he’d been forced to put off for so long, starting with state-sanctioned atheism and educational overhauls, and quickly progressing from there to social reforms, centralised economic planning and the pursuit of autarky.

With the crises of the past two decades finally coming to an end, however, revolutionary leaders and politicians began criticising Mazin’s autocratic rule, calling for the realisation of socialist ideals through worker’s councils and democratic elections.

The Supreme Leader refused to surrender his hard-won powers, but he did grant the Communist Faction — now formally styled as the Socialist Shura of the Union — greater powers, charging the executive committee with the drafting of laws and policy, with the caveat that they had to be ultimately ratified by him.

The Shura immediately began the implementation of their first ten-year plan, a nationwide drive to revive the industries and infrastructure of Iberia, largely left devastated by the Civil War and Great War that had been raging across the peninsula since the 1910s.

At the same time, the Shura began a series of long-promised social reforms, investing heavily into education reform and healthcare packages in particular, quickly followed by the establishment of minimum wage and limits on daily workhours. Maz Mazin immediately shot down any attempts at political reform, of course, with the Supreme Leader gradually cementing his ironclad hold on power.

On the world stage, meanwhile, international sports tournaments and athletics competitions were becoming another theatre in the ideological wars raging between monarchism and liberalism, communism and fascism.

Eager to promote the illusion of internal unity and ideological superiority, Maz Mazin approved the entry of the Iberian Union into the 8th Olympic Games and 1924 World Cup, staged in Paris and Medina al-Gharb respectively.

And the olympic team dispatched to Paris performed admirably, bringing back the third-highest haul in gold medals after Francia and Berber Union, only for the football team to suffer a series of miserable losses at the world cup.

With their impressive performance in the Olympics still fresh, the Iberian bid to host the 10th Olympic Games stormed to victory, with the capital of Qadis chosen as the host city.

These were all mere distractions, however, whilst Maz Mazin directed his undivided attentions and resources to his rapidly-growing military. By the dying days of 1934, the Red Army had rapidly expanded to number almost 150,000 standing soldiers, with a strong core of armour and air support, whilst the Red Navy was transformed into an armada of commerce raiders and submarines, reinforced by a few battleships and ironclads.

Impressive, for just ten years, and the rearmament policy wouldn’t be slowing down anytime soon.

This ambitious build-up couldn’t be concealed forever, however, and Iberian rearmament quickly became an open secret amongst the Great Powers. Jacques Vernier didn’t make any public statements, but he did order the deployment of an additional 130,000 troops to the border, sparking another war scare in the streets of the capital and assemblies of the Shura.

Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, the war in the Caribbean was quickly coming to an end. The fleets of New England and Berber Union had decisively crushed the Almoravid Navy in the early months of the war, allowing the allied nations to occupy New France and Taghzir within the year.

And just like that, after less than a year of fighting, Almoravid Morocco was forced to sue for peace. The triumvirate of viziers ruling the Berber Union were keen to prolong the war, but the prime minister of New England immediately agreed to a separate peace with Morocco, demanding the cessation of Taghzir as a puppet republic to Richmond.

This backhanded diplomacy and blatant powergrab enraged the politicians and public alike in the Berber Union, but they weren’t willing to continue the struggle against Morocco alone, forcing them to ratify the peace treaty and end the war with nothing.

Needless to say, formal relations between Berber Union and New England were immediately severed, but Richmond had already shifted their attentions elsewhere — towards the west, where an Islamic revolution had overthrown their puppet government in North Ibriz, quickly followed by a communist coup d’état in South Ibriz, with both governments adopting a hostile stance against one another and New England.

War was on the horizon in Gharbia, it would seem, and the same could be said for the other defeated powers of the Great War. Across the width of the world, a military dictatorship was established in Armenia whilst fascists seized power in Arabia, with both focusing their hatred and ambitions on the neighbouring Vali Emirate.

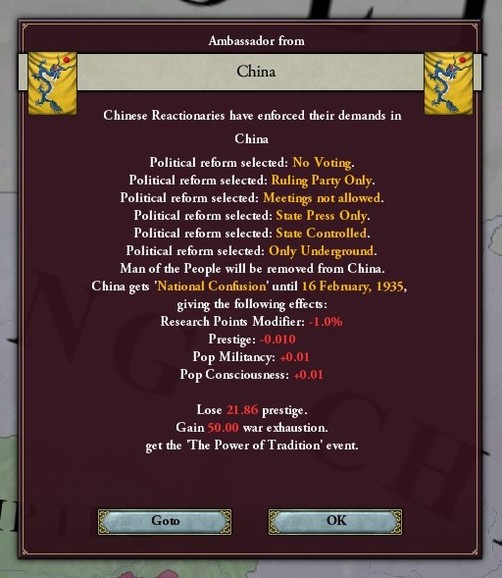

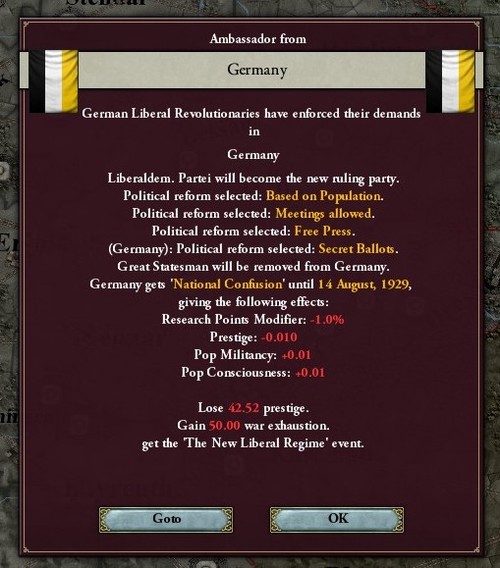

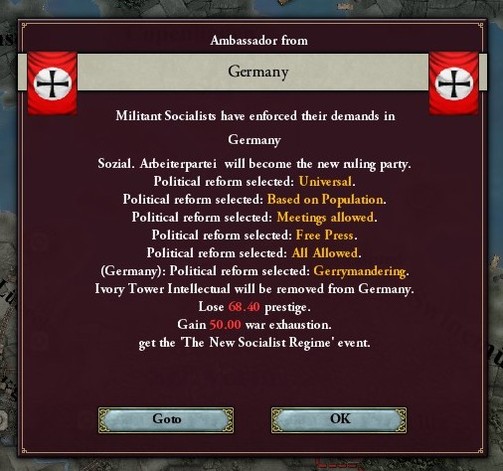

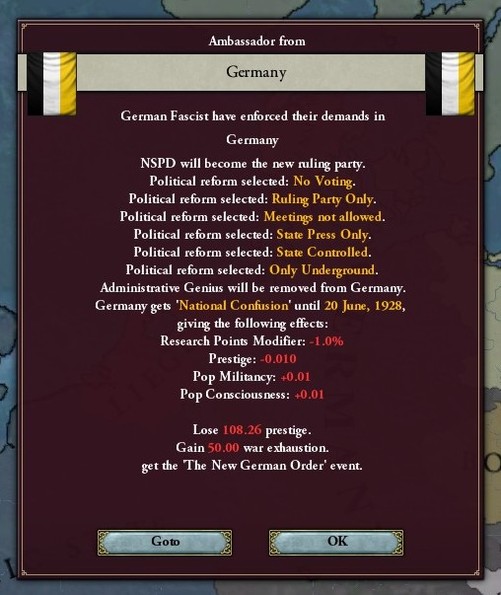

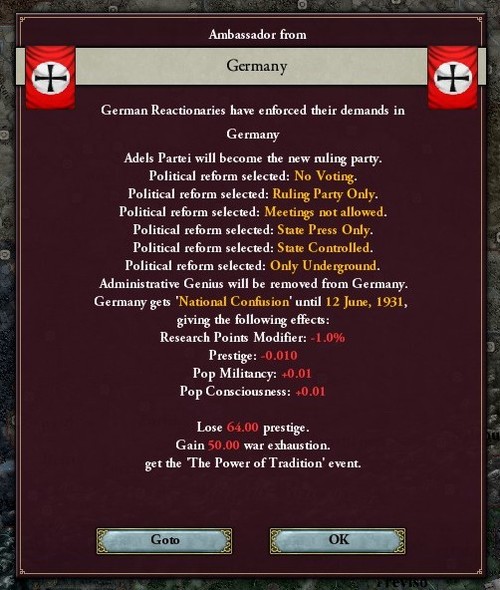

And between the two ends of the earth, the last of the vanquished nations of the Great War had not exactly enjoyed an era of peace and tranquility in the decade that followed the Peace of Prague. In fact, Germany had become a ravaged wasteland of general strikes, popular uprisings, military rebellions, radical revolutions and political coups.

This was a decade-long game of musical chairs, one that saw power seized by fascists, wrenched by republicans, snatched by socialists and plucked by reactionaries. By the first mornings of 1936, it had become clear that this turmoil and unrest could only be decided through violence. It would be mere months before Germany erupted into a three-way civil war, a desperate struggle for power between liberals, communists and fascists.

And the rest of the Great Powers wouldn’t sit idly by, not when the fate of the world was on the line.

The Peace of Prague was never meant to end hostilities, and it would prove to be little more than a respite for the warring empires, a lull in the devastating hostilities, a brief interlude in the Great War. It was an armistice for ten years, and soon enough, the world would be engulfed by war once more.

World map: