Part 107: The Powderkeg of Europe

Chapter 2 — The Powder-keg of Europe — May 1936 to January 1937The year had begun on a quiet note, with a lull in the recent tensions lending weight to the hope that the decade-long peace would yet endure, a hope that would ultimately prove futile.

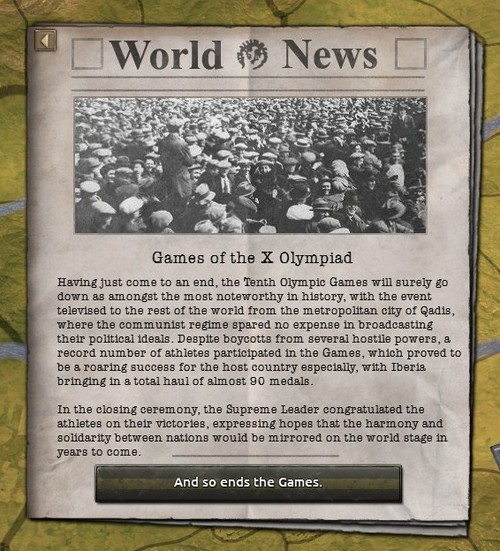

The strained relations between nations had already manifested in several boycotting the Tenth Olympic Games, in protest of the host city being Qadis, a boycott that eventually included the Frankish Realm, German Reich and Almoravid Sultanate. Nonetheless, the Games would prove to be a roaring success for Iberia, which emerged with the largest haul of gold and silver medals, closely followed by the Berber Union and Russian Empire.

The Supreme Leader of Iberia, Maz Mazin, used this global event as a pretext to nurture better relations with several hostile powers, negotiating mutually-beneficial trade agreements with the Balkan Federation, Berber Union and Russian Empire.

And before long, oil, rubber and steel began flowing towards Qadis, much-needed strategic resources that were quickly put to good use.

Speaking of Russia, it would be a momentous year for the Empire, with the 1936 elections becoming the most contentious in recent memory. After months of aggressive posturing and appalling conduct, the pro-isolationist socialist party edged the pro-interventionist liberal party in a narrow victory, with Yuri Antonov using his inaugural address to promise immediate changes in foreign policy.

Across the width of the world, meanwhile, the western hemisphere was weathering turbulent times of their own.

The stock markets in Imariz and Richmond had become notoriously unstable in recent years, with the fragile political situation between Berber Union and New England only aggravating the issue, culminating in the Market Crash of 1936.

And though Gharbian economies would be hit hardest, the crash would reverberate across the globe in months to come, dragging the rest of the Western world into depression with it.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, Maz Mazin was preoccupied with bringing his industry up to snuff, determined to challenge his major rivals in industrial capacity by the end of the decade.

Within a scant few months, the equipment deficit was halved and rapidly closing, so the Supreme Leader shifted some factories to the production of armour and airplanes, with a particular focus on light tanks and fighter planes.

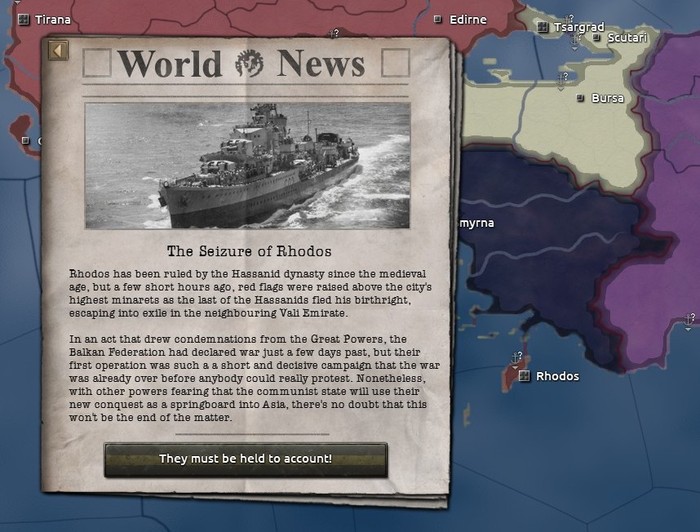

It wasn’t much longer before his attention was drawn east, however. In September of 1936, the General Secretary of the Balkan Federation issued an order for the seizure of Rhodos, with the newly-constructed battleship BBF Jovan firing on coastal fortifications in an act of unsanctioned aggression.

Scarcely a week later, however, and red flags were being hoisted above the island’s highest minarets, with the last emir of Rhodos fleeing to exile in Baghdad.

This blatant aggression was met with immediate denunciations from Russia, Egypt and the Vali Emirate, but little more would be done in the months that followed, with the attentions of the Great Powers quickly sliding southwards.

Despite a number of stunningly-successful operations, Benin had scarcely survived the Great War intact, forced to relinquish vast stretches of population-dense, resource-rich land to Almoravid Morocco. Unsurprisingly, discontent with these peace terms led to the rise of fascism in the post-war years, becoming a political force to be reckoned with in Benin — until now.

Allegedly in retaliation for an attempted coup, royalist forces had launched a sudden and brutal crackdown on rightwing organisations in Benin City, relentlessly imprisoning dozens of fascist agitators whilst the masses strung up thousands more in the streets and alleyways of the capital. By the end of the Battle of Benin City, fascism was effectively eradicated as a threat to the rule of King Akenzu, with the few survivors escaping into Morocco.

With the Great Powers distracted by this sudden flurry of excitement, there was some leeway for the powers of East Asia to advance their own agendas, with the President of Yereven taking the opportunity to declare the revival of Manchuria.

More notably, the Shushõ of Japan fixed his ambitions on a small, strategically-placed island floating in the Yellow Sea.

The operation was meant to be brief and decisive, not unlike the seizure the Rhodos, but poor planning and underestimating the enemy would lead to a drawn-out, fiercely-fought battle that stretched across weeks.

The president of ‘Free Korea’ appealed to Russia and Manchuria for aid, and though the latter agreed to supply arms and money, it wouldn’t be enough. After a bloody assault was launched on the 18th of December, the coastal defenses were finally penetrated and Jeju was subjugated, bringing the island’s two decades of independence to a definitive end.

The war was celebrated as a great victory in Japan, but halfway across the world, the metropolitan city of Qadis was thrust into mourning, quickly followed by the rest of the peninsula.

Maz Mazin was dead.

The Supreme Leader hadn’t been very old, so his death came as an unwelcome surprise to many, and the Socialist Shura immediately descended into scenes of primitive mudslinging, baseless allegations and fallacious condemnations. And with good reason, Maz Mazin had been healthier than ever just a day ago, full of vigour and passion, so how could he have succumbed to death so feebly?

Despite countless accusations of poison and assassination being slung across the assembly, however, the Shura failed to unearth any evidence of foul-play. So the body was cleansed and embalmed, before being put on public display for the masses to pay their respects. All through the display and funeral and parade, however, only a single matter was on anyone’s mind…

Who would succeed him as the Supreme Leader?

In the aftermath of the tragic death, three candidates had emerged to challenge for the esteemed position, all of whom were close allies and advisors of the late Maz Mazin. Known by the revolutionary names they’d been designated at the outset of the Iberian Revolution — Ghiyath, Mizanur, Ikrimah — the former friends immediately turned on each other as they scrambled to secure support for their claim, igniting fears of renewed bloodshed and infighting.

This death marks the end of an era in Iberia, but for the rest of the world, it would be an occasion for celebration and festivities, with the news of the death of Maz Mazin met with revelry in Paris, Marrakesh, Smolensk and even Belgrade.

These debaucheries wouldn’t last for very long, however.

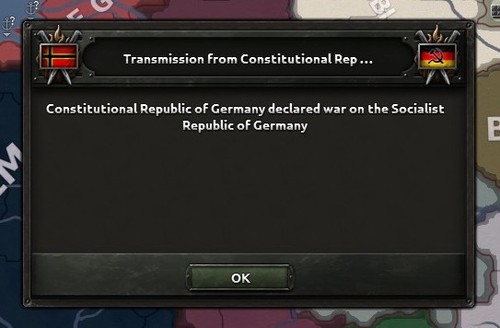

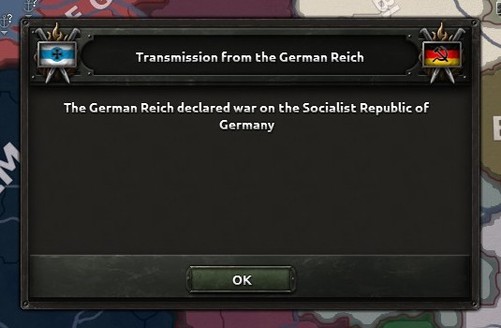

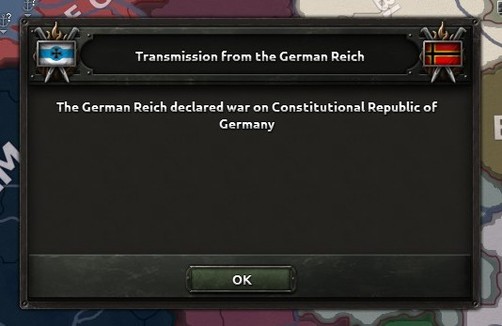

Germany was a land fractured by years of civil unrest and political extremism, hovering on the precipice of civil war for far too long, delayed by brief periods of détente, or desperate appeals for sense from party leaders, or last-minute peaces brokered between rival factions. There would be no such reasoning this time.

It began with the attempted assassination of Manfred Dreyer, a botched operation that was promptly followed with a march on government offices in Hanover, where soldiers were joined by tens of thousands of commoners. The fascist dictator managed to escape the city and flee south, where his supporters began flocking towards München by the thousand, determined to crush the democratic uprising and reinforce fascist rule. And further complicating matters was the declaration of the Socialist Republic of Germany in Frankfurt a few days later, backed by promises of support from Qadis and Belgrade.

Will this be the powder-keg that sets the rest of the continent aflame?