Part 118: Final Epilogue

Epilogue — A Cold War — 1948 to ???Iberia.

Russia.

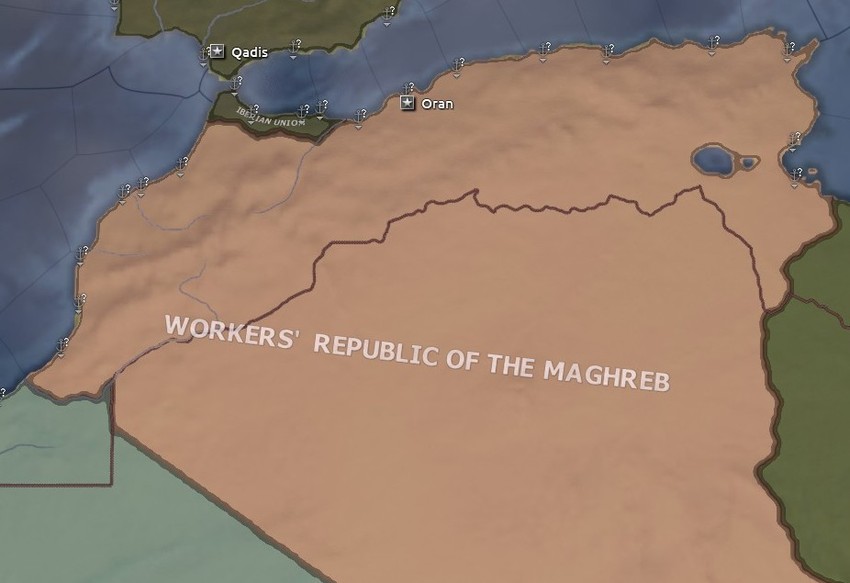

Berber Union.

There is little controversy is saying that, when the bells tolled on the stroke of midnight on the first day of 1948, these three powers emerged as the victors of the World War. An armistice came into force and the guns finally fell silent, but even before the cheering had died and the mourning begun, a new species of war was already underway. A war for information and intelligence, a war with anonymous soldiers and nameless casualties, a war that would be fought and decided on foreign soil all across the world.

A cold war.

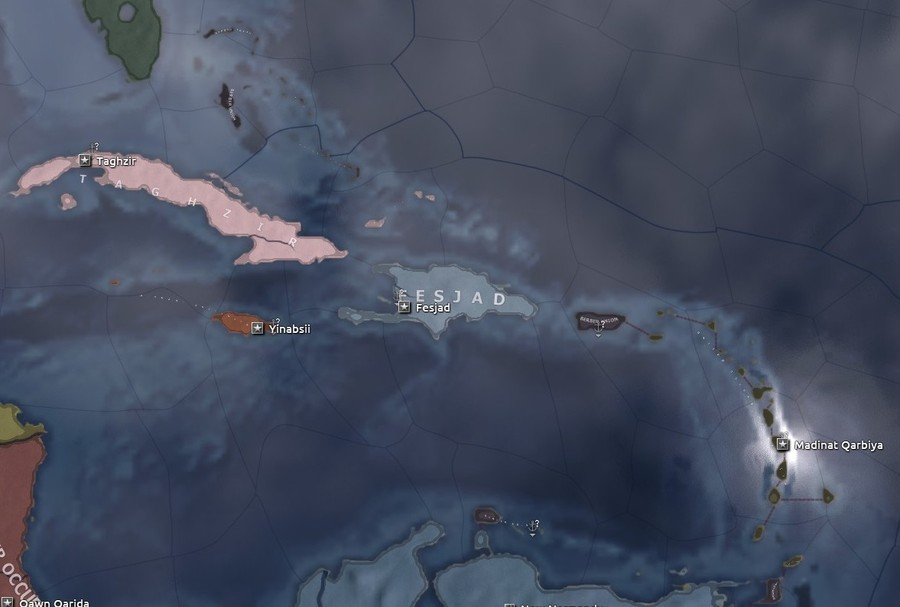

Gharbia

Starting with the last of the victors, the Three Viziers of the Berber Union formally announced an end to hostilities in March of 1948, promising that the fighting in North Gharbia would end in the coming weeks.

That would quickly prove to be an empty promise, however, as Berber troops continued campaigning against Albionoria until year’s end. The fascist administration was eventually toppled, but republican rule in Albionoria began with a succession of weak governments that heavily relied on Berber support just to stay afloat.

South from there, the Kingdom of New England was dismantled in favour of a republic, severely castrated as their conquests over the past century were stripped from them.

Nonetheless, New England’s considerable industry largely survived the war, allowing them to quickly recover and, within a decade, become a leading economy in Gharbia once more. Disgruntled by the concessions they were forced to make, Richmond gradually began seeking an atomic bomb of their own, reaching out to superpowers across the ocean for support.

Around the Mississippi, the long-fallen state of Neimni Sund was revived as a bulwark between Ibriz and New England, benefitting from a close military and economic alliance with the Berber Union.

To their west, a war-torn Ibriz was reorganised under a new republican government, but the inaugural elections were widely boycotted by a distrusting populace. And indeed, the first president of the Republic of Ibriz promptly signed contracts that funnelled oil, aluminium, tungsten and steel southward, beginning a gradual process that would eventually see the Republic of Ibriz become heavily-dependent on Imariz.

Berber domination in Gharbia didn’t go unchallenged, however. The Islamic Republic of Ibriz continued to frustrate the Berbers, with a low-intensity conflict simmering throughout the 1950s until, in October of 1957, a settlement was finally reached to end the fighting between the Islamists and Imariz.

Nestled among the chaos, Waono’s attempts to maintain their strict isolation crumbled in the face of Berber domination, as a military expedition in 1956 forced the neo-feudal state to open their markets to Imariz.

Liberated from Morocco and New England, the minor powers of the Caribbean gradually realigned themselves into the new world order, with their agricultural economies becoming intertwined with Imariz over the next few years.

Closer to home, the Panama Canal was annexed to the Berber Union while its environs were transferred to a military regime, though sedition and agitation continued to bubble across the region.

Similar states were established along Berber borders in South Gharbia, puppet democracies that were wholly subservient to Imariz.

By dismantling enemy governments and redrawing borders in their favour, the Berber Union had certainly won supremacy in Gharbia. But the next few decades would be dominated by their attempts to retain that supremacy, a constant drain on Imariz as ideas of revanchism sprung up in New England, as unrest and crime mounted in Ibriz, as Islamists waged terror campaigns across the continent.

Nevertheless, the immense population, vast industry and nuclear weaponry of the Berber Union paved their way to becoming a superpower, and Gharbia would become their fortress.

Asia

The Almoravids had undoubtedly lost the war, with their world empire and global alliance crumbling after the fall of Marrakesh. The surviving members of that ancient dynasty fled to Usturaliya, where Sultan Ajjedig, despite several failed attempts to retake his homeland, would rule until his death.

Upon the succession of his cousin to the throne in 1955, the new Sultan finally signed a peace treaty with Iberia, followed by a set of liberalising reforms that jump-started the Usturaliyi economy and stabilised the region, allowing the Almoravids to carve out a new place in the world.

And over the years they would become a power to be reckoned with, testing their first atomic bomb in 1958 and launching a massive ship-building program in 1962. As they began expanding their horizons, their budding relationship with the Cedi Empire flourished, with the two monarchies forming the bedrock of an alliance that would soon dominate Asia.

The first problem faced by this alliance was the war in India, where the Bengal Raj was determined to finally unite the subcontinent under a single flag. Once the Almoravids announced their successful nuclear tests, however, this strategy was quickly abandoned, and an armistice was declared a few weeks later.

The resulting Republic of Hindustan was ostensibly a neutral compromise, but the rump state quickly became aligned with the Almoravids, one of the many battlegrounds to emerge between Bengal and Usturaliya.

Looking for allies against Usturaliya, the Bengali withdrew from China in 1959, with their many casualties compensated by new trade agreements and defensive pacts. That wouldn’t do much good for the Mongol Empire, however, as a string of rebellions culminated in the declaration of the Chinese Republic of Hainan in 1963.

This declaration spurred similar rebellions in Eastern China, but the authoritarian democracy in the Federal Republic of East Asia brutally crushed any attempts at separatism, and with military support from the Bengal Raj and technological assistance from the Iberian Union, they would challenge the Almoravids for dominance in Asia over the next few decades.

As the only notable ally of the Berber Union in the east, Japan became the last toehold of true democracy in Asia, boasting freedom of press, speech and movement. Their arms-dominated economy would flourish as tensions spiked between the two power blocs of Asia, but it wouldn’t be very long before Japan also became a belligerent force, turning their eyes on Korea and Otokun.

This wasn’t good news for Otokun, especially when the expensive colony was granted independence in 1965, as their overlords in Benin already had their hands full with the growing troubles in Africa.

Africa

The Kingdom of Benin flourished in the aftermath of the World War, toeing a fine line in the simmering conflict between Iberia and Russia, but they soon became entangled in a string of conflicts stretching across the length of the continent, from Western Sahara to Cape Peninsula.

The principal issue was that of the Congo, where they negotiated the establishment of a condominium with Iberia. This rare attempt at a peaceful transition of power collapsed in the mid-1950s, however, when vicious battles for the country’s mines and minerals (especially those in Shinkolobwe) erupted between regional groups backed by both Benin and Iberia.

Benin would gradually gain the upper hand in this bloody quagmire, bolstered by their geographic proximity and thriving economy. Their fighters were recruited and trained in the South African Union, a dominion erected by Benin in territories captured from the Almoravids, where power was kept from natives and Berbers alike via a policy of divide-and-rule.

Just beyond their borders was the Apanoub Kingdom, where the remnants of the Crusader Egypt government holed up after ceding Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia. Their rule wouldn’t last much longer, however, as a popular revolution finally ousted the dynasty in 1968.

Moving north, we finally reach the spheres of influence of the last two superpowers — Iberia and Russia.

The Middle East

The Armistice of 1948 was followed by several months of negotiation, starting with a strained partition of the horn of Africa into pro-Iberian states in Zanzibar and Ethiopia and pro-Russian states in Somalia and Rift Republic.

Iberian influence in the region would gradually wither and wane, but the mantle would then be taken up by the Socialist Federation of the Mashriq. Cairo and Qadis continued cooperating up until 1970, when Iberia began calling for greater centralisation amongst communist states, immediately triggering a coup d’état that deposed the pro-Iberian regime in Cairo.

This split would have profound consequences in the Middle East, as an increasingly-nationalist government began calling for unity of Arabs, Sahidics and Kurds under the banners of new socialism.

This call was met with a wave of protests and rioting in the Vali Emirate, where Cilicia and Cyprus couldn’t compensate for their losses in the Levant and Hejaz. The social unrest culminated in large parts of Syria, eastern Arabia and Oman breaking away from Baghdad in the early 1970s, quickly dragging the rest of the Middle East into a state of anarchy.

The Socialist Federation of the Mashriq officially intervened in favour of the separatists, and as this crisis finally erupted into blows between Cairo and Baghdad, relations between Qadis and Smolensk plunged to new depths.

To the immediate east, the Turkish rulers of Khwarezm found it impossible to maintain their neutrality as tensions continued to escalate, finally throwing their lot in with Vali and Russia upon the outbreak of war in the Middle East.

The war would stretch across a decade and end with the collapse of monarchy in the Middle East, and one of the key reasons for this defeat was the relationship between the Caucasian Emirate and Anatolian Republic.

Both powers remained closely-aligned with Russia, but a long history of fierce conflict and ethnic hatred made any attempts at cooperation pointless, as outright war between the two powers was only prevented by the looming shadow of Russia.

And that shadow was vast, very vast indeed.

Europe

Russia emerged from the World War with its armies controlling everything east of the River Weser. Having suffered colossal losses in population and industry, however, the ornate facade that was the Russian Republic quickly began to crack and splinter once the fighting had ended.

It started with the President of Russia crushing any attempts to restore the monarchy, instead issuing a warrant for the arrest of any Rurikids in 1949. This was followed by his refusal to surrender war powers, lift the general curfew or reinstate constitutional rights over the next few months… All under the pretence that another war with Iberia was imminent.

And that proved enough to keep the populace in tow up until his death in 1950, when his heart finally gave out. His successor seized power just days later, and immediately began the installation of friendly regimes in Finland, Scandinavia, Denmark, Poland and North Germany, more-so for the tactical advantage than anything else, as he was determined to prevent the Iberians from steamrolling into Russian territory or launching nuclear attacks on Russian cities.

A sound strategy, until it was nullified by the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles in Iberia, briefly shifting the advantage back to the communist alliance.

Similarly, the Balkan Republic was formed in lieu of the Balkan Federation, but the firmly-entrenched socialism in Serbia and Bulgaria contrasted with monarchist traditions in Greece and Romania. Rising tensions, rampant corruption and a stagnating economy placed the Balkan Republic squarely on the road to a bloody collapse in 1977, when the assassination of the president plunged the peninsula into civil war.

Hungary had been rewarded with Dalmatia and Croatia for their sacrifices in the World War, and the kingdom would remain firmly within the Russian sphere of influence throughout the various conflicts of the cold war.

Economic pressure eventually forced the Latin Empire to treat with Smolensk, but the Republic of Slovenia managed to maintain its neutrality in the following decades, becoming a valuable intermediary in disputes between the Russian east and Iberian west.

The Russians and Iberians failed to reach an agreement regarding Central Europe, so as the bloodiest battleground of the World War, Germany was partitioned into a communist south and republican north, but maintaining stability in the region wouldn’t be easy. Sixteen bombs were dropped in four years, and though Germany would slowly recover from this nuclear devastation, the memory of entire cities wreathed in atomic fire would never be forgiven, north or south.

So, from the earliest days of the cold war, politicians in both North Germany and South Germany began efforts to reunify their country, but these efforts were always foiled by Russian and Iberian troops, up until the cold war came to an end at the turn of the century…

East and west also clashed in Bohemia and Vienna, which the Iberians and Russians had similarly partitioned along lines of occupation, right through Prague and Vienna.

These cities became the focus of an intense string of assassinations and coups and counter-coups that climaxed in 1985, when a socialist revolution in Russian-Vienna subverted a democratic election before the results could be made public. Iberia immediately dispatched troops to secure the entirety of Vienna, and with the Russians retaliating by threatening a full-on invasion, the two superpowers were thrust onto the verge of another nuclear war…

Before hydrogen bombs could be exchanged, however, Russia mercifully stood down, allowing Iberian troops to sweep into the city a few days later.

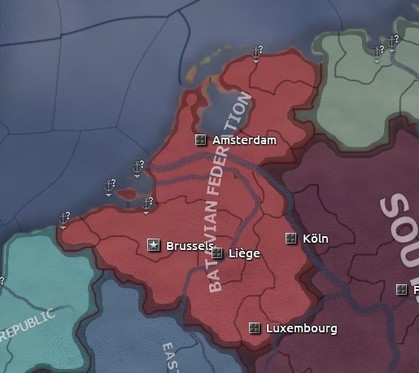

Further west lies the core territory of the Ad Hoc Alliance — Britain, Holland, France, Provence, Italy, the Maghreb.

In Britain, disputes between Dublin and York were a frequent danger to stability on the island. These disputes eventually led to the USCR withdrawing from the Ad Hoc Alliance in 1969, an act that was countered by a brief invasion that toppled the old government and realigned Dublin with Qadis.

France remained heavily-policed by Iberian troops, and though Brittany was absorbed into the Western Workers’ Republic in 1986 and Normandy into the Eastern Workers’ Republic in 1987, any further attempts at integration were strictly denied by Qadis, which maintained an especially-large force in the Paris Commune for fear of rebellion.

Territorial disputes and frequent political interference also strained relations between Qadis and Toulon, with the People’s Republic of Provence only pacified after an army was dispatched to “restore order”, occupying the industrial Languedoc region and threatening their capital.

Being more distant from Qadis, Batavia and Italy were accorded a degree of freedom not extended to other satellite states in the Ad Hoc Alliance, such as limited elections and press rights.

This may have placated Batavia and Italy, but the same wasn’t true for a Palermo that was stripped of their capital, as a string of toothless governments eventually triggered a nationwide revolution in 1990, attracting recognition and support from Russia and Benin.

Worsening relations with Benin would also contribute to a spiralling situation in the south, where insurgency continued to simmer and spit throughout the Maghreb. And despite stationing hundreds of thousands of troops and regularly cycling governors in the region, the widespread unrest eventually exploded into several large-scale uprisings in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Finally, we reach the Socialist Union of Iberia, guided from a regional power that barely survived the Great War to a continental behemoth that emerged victorious from the World War. Mizanur Ridwan continued to lead the Iberians into the early years of the cold war, with the Supreme Leader crushing any dissent in the Ad Hoc Alliance, countering Russian influence on every front, intensifying the nuclear arms race and escalating crises across the width of the globe.

This aggressive policy wouldn’t survive his death in 1966, however, when Mizanur’s successor began championing a new strategy — the Communist Federation, a political and economic union that sought to integrate the various socialist republics of Europe and North Africa into a single superstate. These ideas would be embraced in some parts of France and Italy, but they were largely opposed in Britain and Batavia and violently denounced in Germany, Morocco and Egypt, inviting unwelcome attention from foreign powers across the world.

To many, however, it seemed like the only path forward. And with Russian armies encroaching on Iberian puppets, with the Berber economy expanding at an alarming rate, with Almoravid diplomacy frustrating any attempts to win eastern allies, it was clear that it would take an iron will to realise this ambition.

An iron will and a red army.

———

Final casualties:

Faction map:

World map:

———

Outskirts of New Prague, winter of 1998

She was almost bouncing as she ran, laughing as she chased the dragonfly down the street and around a corner, forcing Alaric to take longer strides just to keep up.

“Eve!” he called after her, and the child staggered to a halt. Sparing the colourful insect one last glance, she turned back to her parents.

“Come on, love,” her mother said, fixing the ribbon in her hair. “We’re gonna be late for the movie.”

The small family took their time as they strolled through the streets, with Edessa filling her husband in on their daughter’s antics that day. He was only half-listening, his mind harking back to a tense conversation with his superior officer at the military base — a stocky, thickset Iberian with a black beard and knack for cruelty.

“Al? Al, are you listening to a word I’m saying?”

“Hmm? Yeah, yeah, she’s a right nuisance. Look, we’re here,” he said as they turned onto a narrow alleyway, carefully stepping around a mound of rubble and debris. “Let’s get inside, it’s freezing.”

The party of three hurried down the alley and into the theatre, where they were shuffled down the halls until they reached a relatively vacant room. Alaric followed his wife and daughter down the aisles, shrugging his overcoat off to reveal a battered-gold uniform before collapsing into one of the chairs.

As people dropped into seats around them, the lights slowly dimmed and words flashed on the massive screen at the end of the room — The Chronicles of Al Andalus.

Alaric rolled his eyes. They could keep churning them out in the old city, but he would never like these propaganda films. They only ever made him angry, and they were always the same — Russians smothering nascent revolutions across Europe, Russians cracking down on worker movements, Russians calling for nuclear war…

Always the same. Alaric clenched his jaw as the scenes slipped past, this time Maz Mazin preaching revolution, this time the Commandant being garrotted by his countrymen, this time Iberian soldiers liberating German cities, this time Russians bombi—then the doors at the end of the room suddenly crashed open with a bang.

“OUT!” A man screamed. “EVERYBODY OUT!”

Alaric’s first thought was work. They found out. Somehow, somewhere, someone must have spoken. And if they knew he was with the Resistance, he would never see the light of day again.

As he sprung to his feet, however, sirens fixed to the ceiling suddenly boomed to life.

It’s an air raid, a terrifying wave of relief washing over him. Then, Fuck me, it’s an air raid.

Spinning on his feet, he swept his daughter into his arms and grabbed his wife by the hand, before turning again and barrelling straight towards the doors. And as the crowd stamped and shoved and shouldered each other, behind them all, a mushroom cloud slowly rose above the city of Prague.

History is just one damn thing after another. — Arnold Toynbee.