Part 16: The Grand Shura

Chapter 16 – The Grand Shura – 1256 to 1270Late in the 1250s, war cries were taken up all across the Muslim world as news of the fall of Jerusalem spread, from Persia to Morocco. After suffering a string of humiliating defeats, the Fatimid Caliph was forced to submit to the Pope’s demands, surrendering the Holy City of Prophet Isa to Christendom and giving rise to the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem - with a vicious Icelandic crowned as king.

Word of this stinging blow spread even to the rocky shores of Iberia, but the Sultanate of al-Andalus had more immediate problems to deal with. After years of internal unrest, yet another Sultan had been cut down before his time, further damaging the legitimacy of the Jizrunid rulers.

Because the young Sultan Abdul-Hasan died without heirs, however, the throne passed to a rather unlikely candidate: a certain ‘Hakam’. Grand Vizier Musa immediately swore his undying loyalty to the new sultan, but he was widely blamed for the outbreak of the rebellion, so he retreated back to his stronghold of Safra just before Hakam reached Qadis.

Crowned just days after his nephew’s death, Hakam had an interesting background. He had born been a bastard to Sultan Fath, and upon his father’s death, he inherited a few small castles in Marbal-la, a poor and desolate region just north of Algeziras.. Despite the scandalous circumstances surrounding his birth, however, Hakam quickly gained a reputation for being a shrewd and effective administrator, and the panicked Regency Council invited him to take the throne after the death of Abdul-Hasan.

There was still some opposition to his coronation, but there were far more pressing problems to deal with just then, and most of the nobility were simply glad that an adult had inherited the Sultanate this time. Hakam was crowned in a rushed ceremony at Ishbiliya, where he received the ceremonial sword and robes along with vassals’ pledges of loyalty, before leaving just days later to lead the loyalist effort.

Hakam was a clever man, clever enough to know that he was no tactical genius. Instead, he left the details to his generals and hung back during battles, which proved to be the right decision. Under the command of more able officers, the veteran Andalusi loyalists began winning battles once more, handily crushing two rebel armies in quick succession.

After forcing the rebel leader Ismail to retreat, the loyalists stormed several forts and captured them, landing another blow on the rebel effort as the tide shifted against them.

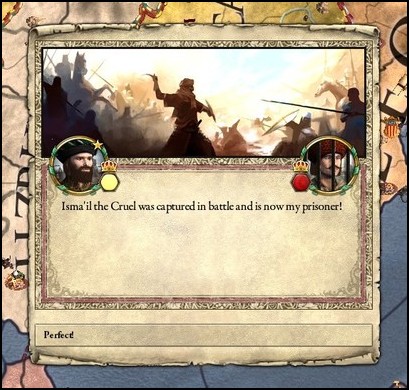

Still, Emir Ismail was a resilient man, and he refused to surrender. The loyalists chased him halfway across al-Andalus before pinning him down at Granada, where they proceeded to annihilate what was left of his army.

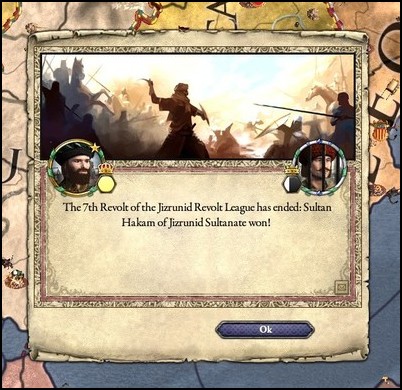

Even better, Ismail himself was captured whilst trying to flee after his loss, and was promptly clapped in chains. With the capture and imprisonment of their leader, the rest of the rebels finally surrendered, bringing an end to the bloodshed.

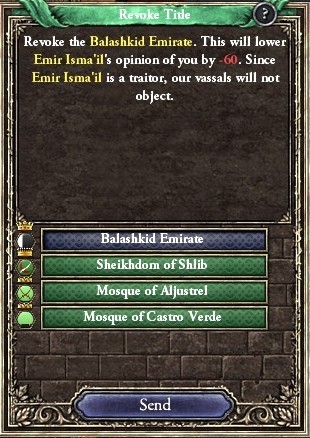

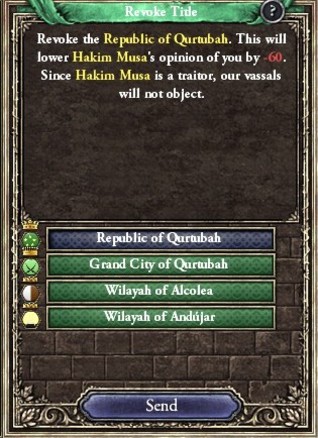

Sultan Hakam didn’t have the rebels tortured or executed - he wanted to mend old wounds, not make more enemies - so instead he just threw them all behind bars, though he did revoke most of their titles and possessions, redistributing them to his own allies.

With that done, Sultan Hakam could finally return to Qadis and move into his royal apartments, though many were still suspicious about his motives. Even Hakam’s closest allies were surprised when he didn’t order the execution of the rebel leaders, when all previous Sultans were all too happy to mutilate and torture their enemies without end.

This surprise was exactly what Hakam was hoping for. Al Andalus had already endured two centuries of hard, brutal rulers, so it was past time she had someone different. Hakam had grand plans, but they wouldn’t be achieved if he was constantly fighting his own vassals, so he was determined to avoid that by being a more just ruler. Why waste men and money in fighting rebellions, after all, when he could get whatever he wanted through diplomacy?

Hakam, in another break with tradition, decided to prioritise internal development over war with the northern Christians. Before he could begin doing so, however, even more problems cropped up.

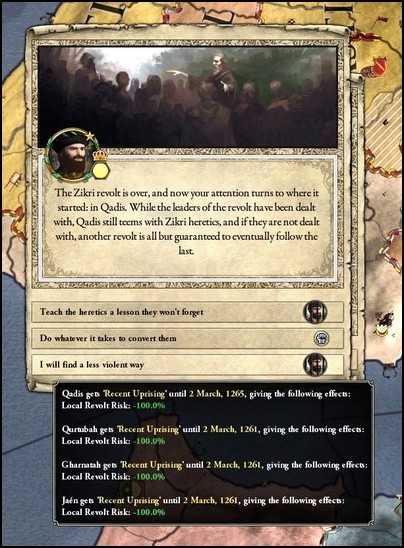

The recent tumultuous years had allowed heresy to take root within al-Andalus, with preachers, peasants and nobles all openly declaring their profession to the Zikri heresy. The Utmani Edict in particular had fanned religious tensions, and though Hakam refused to repeal the decree, he was determined to mend the rift between heresies.

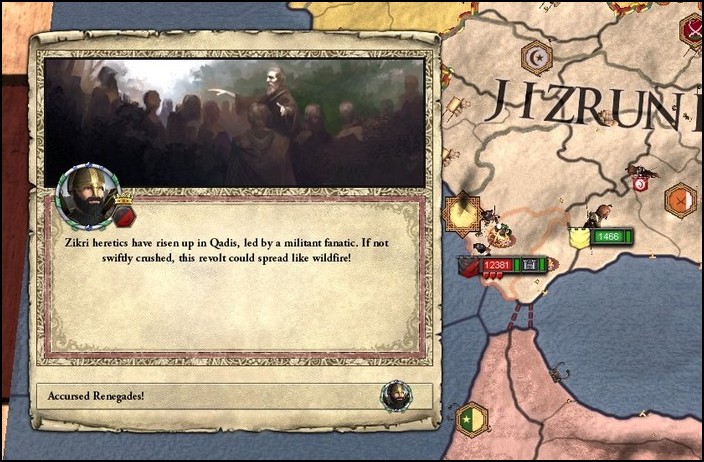

Recent sultans had been too occupied with wars and rebellions to deal with the heresy, so the Zikri were able to spread without opposition. Now that peace had returned to al-Andalus, the more fanatic heretics had begun demanding independence, claiming that the Jizrunid Sultans was trying to stamp them out.

A large riot broke out in the very streets of Qadis, to Hakam’s surprise. He believed in tolerance over aggression, but he would not let his kingdom fracture because of a few unruly peasants, so he raised a large army and brutally suppressed them to a man.

However, again surprising many of his vassals and courtiers, Hakam didn’t go to extremes. He didn’t begin torching random villages or executing innocent men, as some of his predecessors had, he instead opted for a less violent method of dealing with the Zikri fanatics.

Mercy.

Sultan Hakam was no fool, however, and it was impossible to forget the assassinations of his father and brother. Hoping to avoid the same fate, Hakam began investing into his own protection. Not only did he expand his spy network and begin infiltrating various courts, but he also created a new order of royal guards, whose sole duty was to defend his person day and night.

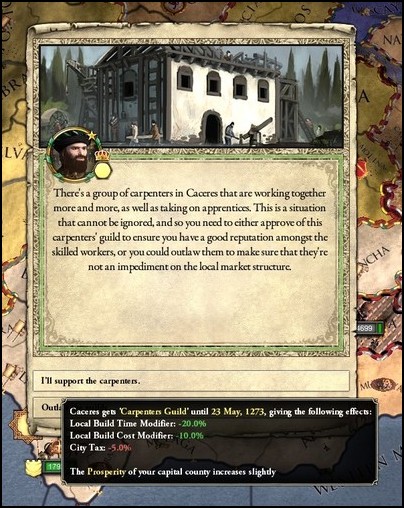

With the fires of rebellion finally beginning to die down, Sultan Hakam turned his attention to his kingdom. The Jizrunid treasury was not in good shape, but Hakam took loans and donations to initiate new public projects, ranging from messenger systems to trading posts.

He also expanded the markets of Qadis, investing hundreds of dinars to attract more merchants to the budding city, and founded several builder and carpenter’s guilds to speed the construction up. One of his most famous constructions would be the Jizrunid Mausoleum, the crypts of the royal dynasty, where he transferred the bodies of his nephew, brother and father, along with the bones of his grandfathers and great grandfathers - all except for one, the infamous Sheikh Az'ar, whose tomb was revealed to be empty when dug up.

Sultan Hakam was not simply content with developing al-Andalus, however, he wanted more.

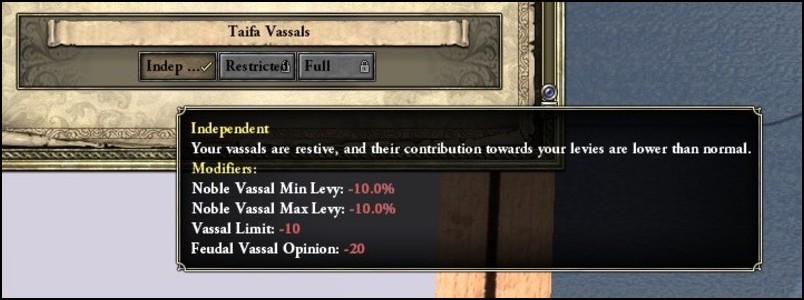

His ancestors had managed to revive the legacy of al-Andalus and bring an end to warring states period, but the different Taifas of Iberia still lived on, with Emirs ruling their domains with almost-complete autonomy. Hakam wanted to bring an end to the Taifa system altogether, and create a stronger and more united al-Andalus from it, all under the authority of the Sultan in Qadis.

Such a thing is easier said than done, however. The Emirs were very powerful, and they wouldn’t surrender that power to anyone, not even a Sultan. Hakam had to unite them behind him before even broaching the matter, and there was no better way to unite a bunch of nobles than through a common enemy.

And luckily for Sultan Hakam, the perfect opportunity to declare war on said enemy arrived soon afterwards.

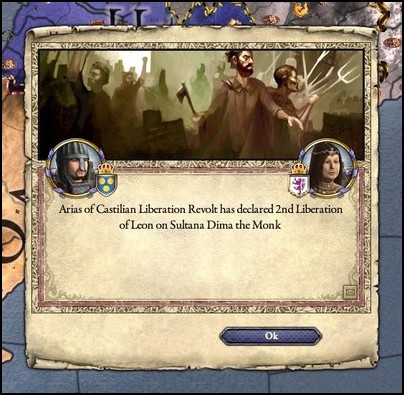

A large revolt broke out in León in the summer of 1261, and with Queen Dima’s attention focused on that, Sultan Hakam decided to strike. Near the end of the year, he delivered a sermon in which he declared war on the Kingdom of León, which even surprised his own subjects, because nobody had really expected Hakam to be of the warring sort.

And in fairness, Hakam certainly didn’t enjoy war, not unless there was some benefit to it. His prepared armies marched into León unopposed not long after his sermon, whilst the different emirs of al-Andalus scrambled to do the same, hoping to carve a slice of the riches for themselves. Hakam picked his commanders carefully, however, avoiding the famous names and powerful lords - including Musa, who was still holed up in his stronghold.

Sultan Hakam didn’t expect the war to last too long, he didn’t want much out of it. Still, the Christians were not known to surrender without bleeding first, and Queen Dima sent a large army to engage the Andalusi whilst they were sieging down a well-fortified castle at Valencia.

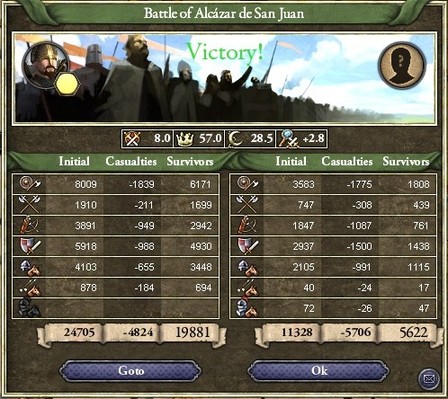

Hakam hung back whilst the battle raged, as per usual. The fighting was thick and bloody, and neither side managed to gain the advantage until the Muslim reinforcements arrived, doubling their number. Outnumbered and surrounded, the Leónese were quickly routed soon after, leaving thousands of dead littering the battlefield as they fled northward.

With the first Christian attack thrown back, the Muslims spread out and began sieging down a few castles and fortresses, capturing a number of them over the next few months.

Mursiya and a good chunk of Catalonia quickly came under Muslim occupation, but the longer the war dragged on, the more dangerous it became. Just a year into the conflict, Castille and France both pledged troops to help defend Queen Dima, and Sultan Hakam realised that he would have to either score a decisive victory very soon, or back out altogether.

Hakam was far more ambitious than he was cautious, and opted for the former. He directed his generals to position an army near Toledo to act as bait, and once it was engaged, to pour a second reinforcing army onto the battlefield.

The Christians chanced upon the 10,000-strong army when it was still near Calatrava, and engaged it with a slightly superior force, hoping for a quick victory. After another close battle in which reinforcements made all the difference, however, the Leónese were forced to fall back in disarray once again, defeated and broken.

Despite these losses, the Castilians and French wanted to keep the war effort going, hoping to counter-attack with fresh armies. Unfortunately for them, disaster struck in León when Queen Dima fell ill and died, leaving her kingdom to a mere child. That was the final blow, and the Leónese were forced to sue for peace, caving to Hakam’s demands.

Sultan Hakam didn’t take much, settling for a rich stretch of land and yearly tribute, as was usual. He gained far more in prestige and influence than he did in riches, however, and that was exactly what he needed to set his plans in motion.

Armed with this, Hakam invited his most powerful Emirs and Sheikhs to a 'Grand Shura', as he called it. Hosted at Qadis, Hakam began a series of negotiations in which he tried to convince his vassals into ending the Taifa system altogether, promising everything from land to gold in compensation. The histories write of countless arguments flaming up between rivals, a myriad of insults slung against different factions, suggestions and promises brought up and shot down like rabid dogs. Sultan Hakam was adamant that there had to be reform, and the nobility were unwavering in their refusal to surrender their power.

In the end, a settlement was reached, but it didn’t satisfy either side. The powerful lords of al-Andalus agreed to curb in their autonomy by a small degree, pledging more troops and taxes to the crown, but only because they were granted permanent life positions on the enlarged Advisory Council.

Sultan Hakam was pleased, but he still was not satisfied, and was determined to bring an end to his vassals’ autonomy altogether.

That would have to wait a little longer, however. Mere days after the Grand Shura came to an end, envoys and messengers arrived from the Kingdom of Castille, carrying words of war with them.