Part 17: End of the Old Taifas

Chapter 17 – The End of the Old Taifas – 1270 to 1276In the years since he was crowned Sultan of Al Andalus, Hakam has gradually grown to become a well-respected ruler, by both allies and enemies alike. He prized internal development above all else, striving to reform his kingdom into a more united, structured entity. Like all good Sultans, however, he had also proven his courage on the battlefield, scoring a number of victories against León.

It is only as 1270 dawns, however, that Hakam is presented with his first true test. The Kingdom of Castille-Portugal was a powerful foe, and King Morcaer was determined to resume the Reconquista and see Sultan Hakam humbled.

Ordinarily, Castille and Al Andalus would be fairly evenly matched, both were large and wealthy kingdoms. Al Andalus had spent the past few years in a war against León, however, and both its manpower and treasury were exhausted.

Nevertheless, Hakam couldn’t just give up without a struggle, so he threw together as many men as he could and began the march northward. If Hakam was to have any hope of victory, then he would have to strike first, hard and decisive.

The early months of the war consisted of a string of Andalusian victories, though they were against much smaller, weaker armies. Sultan Hakam accompanied his 12,000-strong army throughout the entire campaign, delivering countless speeches to inspire his soldiers whilst his generals agonised over tactics and strategy.

Eventually, King Morcaer's forces managed to rally in the north, merging into a single substantial army. He pushed south and prepared to invade Al Andalus, only to find his route blocked by Hakam’s army, which had a slight numerical disadvantage.

Morcaer had the advantage of friendly territory and numbers, so he decided to press forwards and engage the Andalusi anyways. The ensuing battle of Portalegre raged for hours, a heated frenzy of steel and blood, before a Muslim counterattack finally routed the Castilian flanks. The Christians retreated hastily, taking heavy casualties as they did so, handing the first significant victory of the war to Sultan Hakam.

The Andalusi didn’t just let the enemy slip away, however. At Hakam’s insistence, the Muslim generals pushed the army into a forced march, chasing down the broken Castilian army and engaging them again a few weeks later.

Their morale already shattered, the Christians had neither the time nor the will to put up a solid defence, and were massacred in their thousands in another battle. Yet again, the battle ended with an Andalusi victory, and the sun set with cheers and celebration in Jizrunid camps.

With two decisive victories on the battlefield, and the enemy army all but destroyed, the war began turning in favour of the Muslims. Still, the Sultanate was beginning to strain under the war effort, and Hakam was eager to end the conflict. So the Andalusi pressed northeast, and just a month later, they were scaling the walls of Burgos.

The Castilian capital was famed for its soaring churches and fabulous palaces, but not so much for its defenses, and the Muslims were in Burgos within mere weeks. The city was sacked without mercy, and over the next few days, large caravans stocked with immeasurable wealth began trickling towards down the stone roads towards Qadis.

It was only now that Sultan Hakam agreed to end the war, for the time being. Al Andalus needed to recover, but this would not be the end of war with Castille, not by a long shot. This had been the second time that King Morcaer had declared war on Hakam, so it was obvious that the fool would do anything he could to destroy Al Andalus, the light of Islam in the west.

The fact remained that any combined Castille-León attack would be very dangerous, one that Al Andalus would struggle to win. The only way to end that threat was to destroy the northern kingdoms once and for all, bringing all of Iberia under Andalusi control.

The next few months flew past in a flurry. The royal budget recovered and the treasury began growing again, but Sultan Hakam focused on his relations with his vassals above all else, sending messengers laden with gifts and conducting dozens of state visits. The Sultan scarcely spent any time in his capital, but he did manage to father two sons on his concubines, with the babes sent to Qadis to be raised and tutored.

And all the while, he kept an eye on the north, waiting for an opportunity to uncloak itself. As the months turned into years, he began preparing for another great war with the Christians, ready to spring into an offensive at a moment’s notice.

His long-awaited opportunity arrived in the summer of 1274, when civil war broke out in France.

France had become increasingly interventionist over the past decades, and they certainly would have involved themselves in another Iberian war. Only now that they were distracted did Sultan Hakam feel confident enough to strike, and in a damning sermon, he declared holy war on Castille.

The Andalusi levies had been raised and ready for months now, and they swept into Castilian territory even before the envoys reached Burgos. A panicked King Morcaer quickly raised a large army and threw it at one of the Andalusi armies, hoping to defeat it before reinforcements could arrive.

Andalusi commanders were prepared for the rash decision, however. No reinforcements were needed, all it took were a few organised retreats and well-timed counterattacks before the Castilians collapsed, leaving a mountain of dead Christians as they pulled back into friendly territory.

The Castilians retreated in disarray, and over the next few months, large chunks of Beja fell to Andalusi occupation. King Morcaer, however, was a resilient man. He managed to scrounge together another army and, in an unexpected move, decided to throw it all at a numerically-superior Muslim army.

The Castilians put up a surprisingly good fight and very nearly came out on top, before the Andalusi managed dismantle one of the enemy flanks and send them scattering.

Sultan Hakam, now sure of his victory, reached out to King Morcaer to begin peace negotiations. Morcaer refused to treat with him, however, only infuriating the Sultan. his reasoning became clear a few days later.

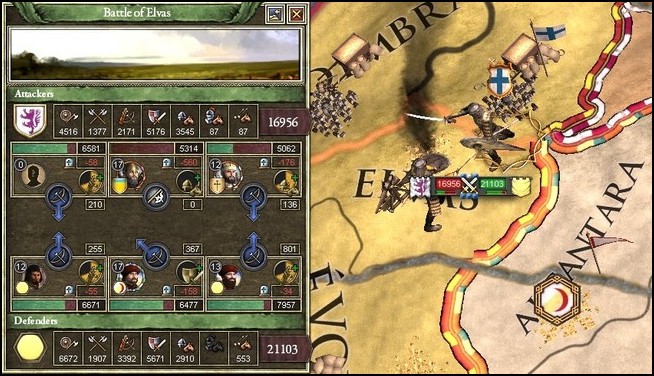

Morcaer's reasoning became clear a few weeks later, however, when the Andalusi marched northwards to besiege Porto, only to be brought to a sudden halt by another massive army, flying Leónese colours.

Andalusi generals had to scramble to bring order to their ranks as the battlefield erupted into a storm of swords. Sultan Hakam sent reinforcements pouring into the field within hours, but the Castilians were doing the same from the north, each side hoping to overwhelm the other through numbers alone.

The chroniclers write that the field of Elvas was forever destroyed that day, that trodden grass drowned in seas of blood, that thousands of men suffocated under mounds of lifeless flesh, that the most animalistic of sins reigned for hours without end.

Like all things, however, this battle eventually came to a close. It ended in another Muslim victory, but cost had been very high, and the battle of Elvas ranked amongst the deadliest of the many Iberian battles.

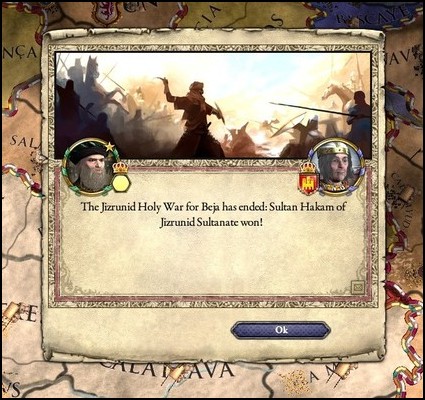

With both Christian powers defeated, and with no hope of another ally swooping in to rescue him, King Morcaer was forced to admit defeat.

Morcaer lost much more than his pride in the ensuing peace negotiations, forced to cede all of Beja to Sultan Hakam, as well as large sums of gold. Al Andalus now swept over half of all Iberia, turning it into the undisputed power of the region, a far cry from the humble Jizrunid beginnings.

Sultan Hakam didn’t care much for all the land he had just gained, however, he saw only opportunities. The following summer, he called a second Grand Shura, summoning all of his powerful vassals and influential landlords to another council.

This time, now that he personally ruled over most of Al Andalus, he found his emirs and sheikhs far more receptive than they’d previously been. Long weeks of negotiation followed, with Sultan Hakam making countless promises and granting endless favours to his vassals, and extracting the same. In the end, Hakam finally accomplished his life's ambition, with his vassals agreeing to abolish the Taifa system once and for all, finally uniting Al Andalus under the authority of Qadis, and thus the Jizrunids.

With that, Sultan Hakam returns to his palaces, finally satisfied. His life’s ambitions have finally been realised, but little does he know of the pandora’s box he has just opened.

During the negotiations, Hakam agreed to replace the Advisory Council with the Majlis al-Shura, or more simply the Majlis. The Majlis was intended to be a great council permanently seating all of the significant estate-holders in Al Andalus, giving them a voice and a say in the ruling of the kingdom. Hakam saw it as a better alternative to the Taifas, and while it is true that the Majlis currently holds nothing more than advisory powers, it is a platform on which the estates can expand their influence and curtail that of the Sultan.

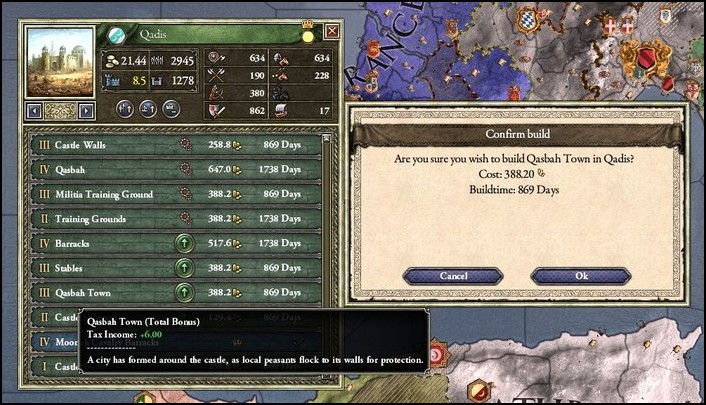

But that is a problem for another time, and another sultan. Hakam spent the next few months in Qadis, using Castilian gold to establish new libraries, fund countless mosques, and expand marketplaces. He finally indulged in some pleasures, growing soft and portly on rich foods, spending long hours with his nose buried in books, and finally spending time with his growing sons.

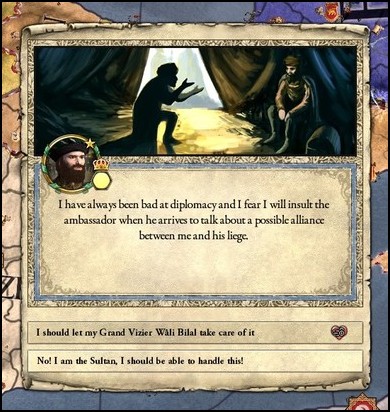

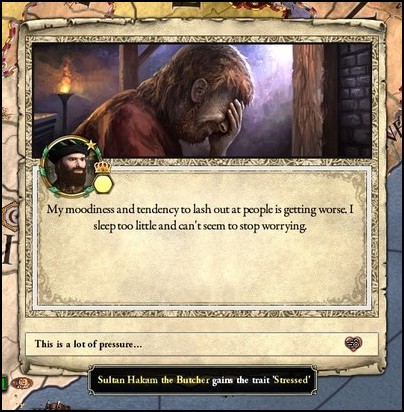

By 1275, however, Hakam was an old man. Not only was his back bent and his hair graying, but his mind was growing increasingly frail, making it difficult for him to rule with the same authority as he had previously. Still, nobody dared suggest that the Sultan surrender his power, and he suffered for it.

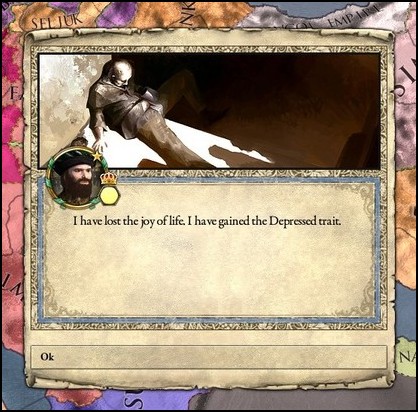

Sultan Hakam became more and more distraught as time progressed, forced to watch his own body failing him, and yet powerless to do anything about it. It's enough to drive any man to madness, and despite all his achievements, Hakam was still just a man.

Sultan Hakam spent his last days reading old tomes, roaming the gardens of his palaces, and playing with his grandchildren. He was found dead in his rooms early in January of 1276, aged 50, passing away due to 'natural causes', or so his successor insisted.

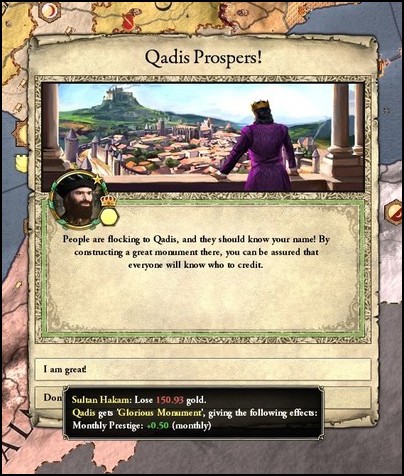

Sorrow poured into Qadis from all across Al Andalus as the news spread, and tapestries, portraits, poems and books were commissioned in honour of the Sultan, a man far ahead of his time. By far the most expensive of these monuments was the gigantic statue raised in front of the royal palaces of Qadis, capturing Sultan Hakam at his greatest: a powerful young man full of hopes and ambitions, and more than enough determination to see them through.

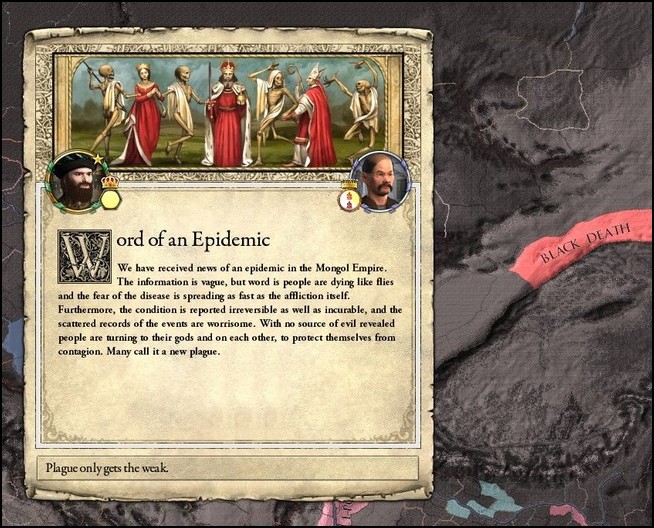

A period of mourning occupies the next few weeks, but unbeknownst to them, the people of Al Andalus will soon be mourning much more than a dead king. Inauspicious rumours have been travelling the paths of the Far East, with word of a Great Leveller slowly trickling down the Silk Road, carrying infestation and depravity with it, reeking of death and perversion, the very substance of the devil.

The Black Death is coming.

edit:

So this is where the Majlis comes in, a national assembly in which the influential nobles, clergy and merchants (you guys) of Al Andalus vote on the future of the kingdom. There probably won’t be any big votes until EU4, but this seemed like a good time to bring the Majlis in, narrative-wise. For now, like I’ve already said, the Majlis is limited to advisory roles. Still, if we get a weak-willed Sultan and an interesting scenario comes up in CK2, I’ll probably hold a vote.