Part 18: Black Death

Chapter 18 – The Black Death – 1276 to 1288With the passing of Sultan Hakam, an era has come to an end. Modern historians unanimously rank Hakam amongst the greatest of Andalusi, not least because he managed to both expand and centralise his kingdom, laying down the foundation on which his successors would build an empire.

Not just yet, however, and certainly not with the new Sultan Fath II.

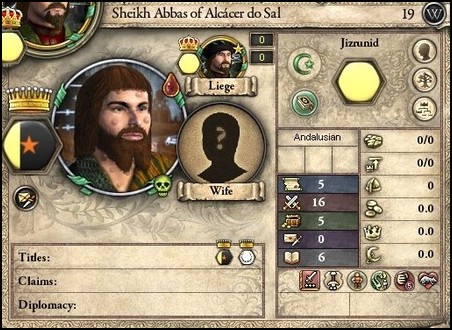

Fath was the eldest of Hakam's sons, and he succeeded to the throne with little opposition. He had only one brother - named Hakam, for his father - but he would quickly retreat from the public eye, taking charge of his father's poorer estates in Marbal-la, where he had built his foundation all those years ago. There, Hakam would establish a cadet dynasty of the Jizrunids, founding a line that would stretch through the centuries and into the modern era.

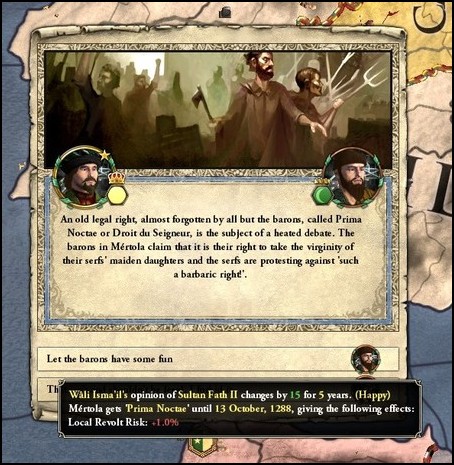

Our story continues with Hakam's firstborn, however. Fath was an ambitious man, with his eyes set on expanding northwards, so many of his vassals were initially hopeful that he would make a good ruler. The young sultan was dragged down by his decadent and downright cruel tendencies, however, which ranged from alcoholism to far more sickening habits...

Fath was coronated in an elaborate ceremony, in which he proudly donned the ceremonial robes and raised the scissored-blade to the heavens, accepting oaths of allegiance from his vassals. Even as they swore their eternal loyalty, however, courtiers and servants and maids whispered of Fath's dark youth, trading stories and tales - some said Fath had raped the wives of his serfs, fathering a string of ill-born bastards; others others claimed he staged mock duels, where he ordered servants to fight to the death; others still insisted that he and his demented cousin played gruesome games in the woods, in which they would hunt and kill humans for sport.

With these rumours swirling around the royal court, it wasn't surprising to find that many of Fath's more powerful vassals were rather... distrusting of him, to say the least.

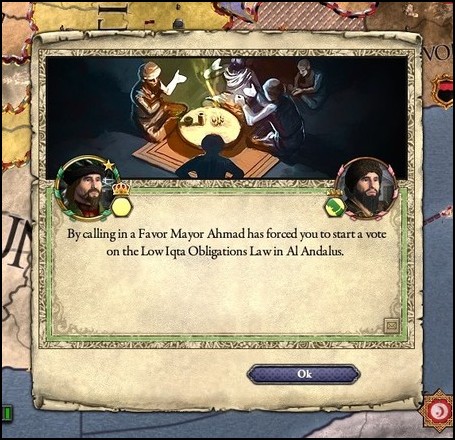

Just weeks after being crowned, Sultan Fath was thrown into the first of many crisis, in which the Majlis demanded that the tax burden placed on them be eased. Before Fath knew what had happened, the Majlis voted on the issue and, predictably, decided to ease their obligations to the crown.

This was a clear violation of their preset advisory boundaries, and as this was explained to him, Sultan Fath became angrier by the second. He knew that he would need alliances with the dominating voices in the Majlis if he was to control it, alliances that he simply did not have, so Fath decided to take a more covert route.

Namely, murder.

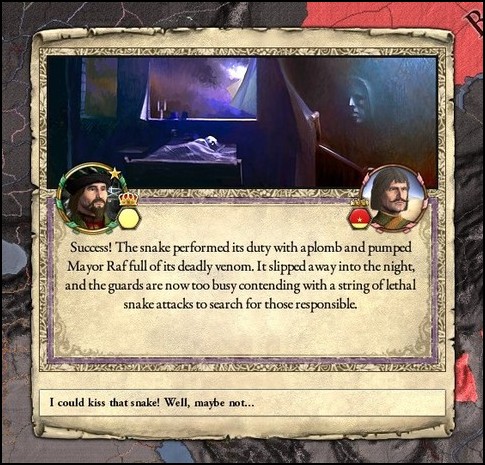

Fath decided to start with Raf Abbadid, the influential and absurdly-rich wazir of Malaqa, who had led the effort to ease the crown taxes.The next few months flew past as Fath gradually built up a spy network, his agents infiltrating Raf's courts and his informers worming their way into his councils, buying off local courtiers and bribing guardsmen. Once he had every route in and out of Malaqa mapped, with his moles situated along the parapets and in the castle, Fath finally gave the go-ahead.

In the dark of the night, an assassin had slipped into the royal palaces through an open side-gate, drifting through empty halls and past vacant chambers, until he reached the apartments of the wazir. The doors were unguarded, and the assailant crept inside, rolling a piece of silk between his fingers. Five minutes later and the deed was done, with the wazir suffocated and unbreathing on his soft cushions.

The assassin stole away, leaving behind a dozen snakes to take the blame, and disappeared into the countryside with a heavy purse weighing him down.

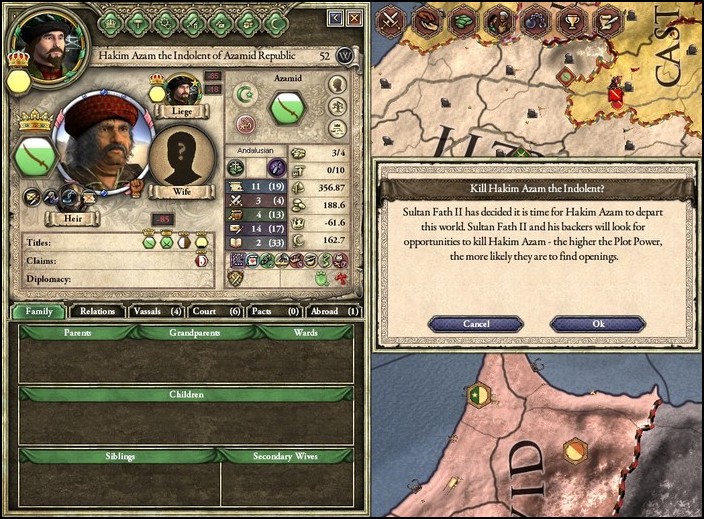

With that done, Sultan Fath could turn to his next rival - Hakim Azam, the leader of an anti-Jizrunid faction in the Majlis al-Shura. Azam was a blue-blooded aristocrat, so he would be harder to gain access to, but Fath managed to formulate a plan within weeks.

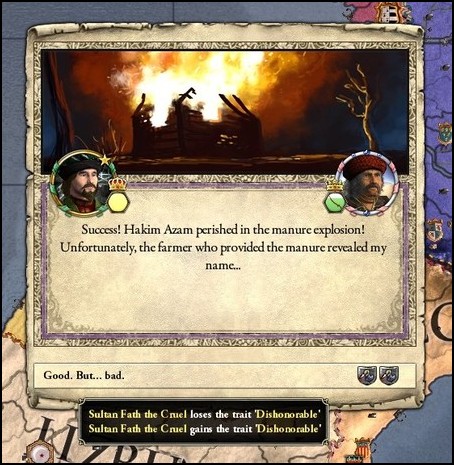

An explosive substance - very expensive and exceedingly rare - was packed in one of Hakim's coining works, and when the sheikh arrived for his routine inspection, the spark was lit and the powder was ignited. Half the building collapsed on top of Hakim, burying the noble under tons of wood, thatch and heavy metal, from where he would never rise again.

Unfortunately, the assassin was unable to escape the scene this time, pinned to the floor by a fallen beam. He was quickly taken to custody and questioned, and within hours, he had given up everything he knew.

As word of Fath's spy network quickly spread through Iberia, the emirs and sheikhs of Al Andalus erupted into a frenzy, denouncing the sultan for his transgressions. Led by sons of Hakim Azam, factions quickly began forming against Sultan Fath, determined to overthrown and replace him. Within mere weeks, half of Al Andalus had united against him, with Fath desperately retreating to Qadis with his loyalist forces.

Just before this unrest erupted into large-scale revolt, however, a far more dangerous threat arrived.

For the past few years, news about a devastating plague in the East slowly spread through Europe. Marked by gruesome pustules that spewed pus and blood, this plague was said to be unlike anything ever witnessed before, killing royalty and peasantry without discrimination, striking down hundreds of thousands within the space of mere months, laying waste to vast stretches of rich and fertile land…

For a few months, this devastating plague was contained to Asia, but Venetian traders unwittingly carried it back to Europe with them. The Black Death, as it would come to be called, spread at terrifying speeds through the Balkans before storming into Central Europe.

For about a year, the plague wreaked havoc across the continent, utterly demolishing any semblance of society and hierarchy all across Italy, Germany and France. It was unable to penetrate the Pyrenees, but late in 1276, a foolish Sicilian merchant docked at Almeria, bringing death and sorrow with him.

The plague cut through Iberia like a scythe through wheat, snaking its way into every town and store, every city and house, every fortress and citadel. Within weeks, the population was plummeting and people were dropping like flies, unable to halt the advance of death.

Understandably, with mountains of dead bodies piling up all across al-Andalus, nobody had much time to overthrow Sultan Fath.

Fath didn’t have enough time to even breathe a sigh of relief before the plague hit Qadis, however, and it hit the capital very hard indeed.

Three of Fath’s wives died in quick succession as the plague swept through the capital, shortly followed by Abbas, his cousin and childhood friend. The distraught sultan reacted to this with pure rage, executing any physician who failed to cure Khadija, his servant and long-time lover.

Unfortunately, the Black Death would not be denied, and she too died amidst violent coughing fits.

Fath stayed by Abbas and Khadija’s side until they each breathed their last, holding their hands and comforting them. Whilst this undoubtedly helped their passing, it wasn’t exactly the best way to avoid the plague, and Fath soon began showing the symptoms himself.

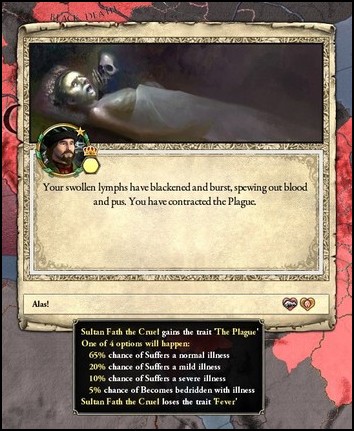

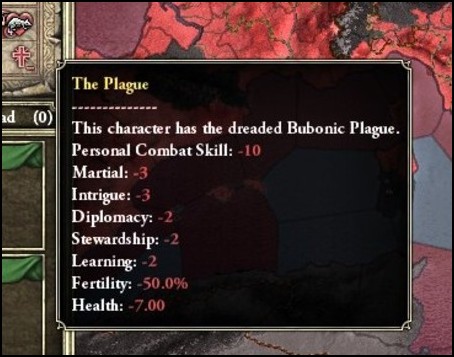

And indeed, just weeks after it arrived in Qadis, Fath was diagnosed with the bubonic plague. The Sultan collapsed whilst he was drowning his sorrows and, after a short consultation, was given mere days to live. He was as good as dead.

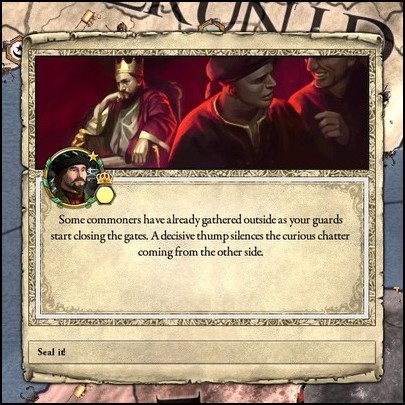

Fath was resigned to his beds, struggling through unbearable pain as gigantic lumps grew all over his body, hard and knobbly to the touch. With the Sultan unconscious more often than not, two high-ranking viziers of the Majlis took control of Qadis as regents, quickly shutting the gates of the Royal Palace and beginning the process of quarantine.

The next few days flew past in a blur, and in a miraculous turn of events, the Sultan somehow managed to survive the most dangerous period of the illness. Nobody really knows how he did it, when tens of millions of people were dying all across Europe, but the royal physicians were immediately congratulated for the impressive feat - they were certain to be rewarded for saving the sultan's life.

That, however, was not the case. Fath himself claimed that he had survived the plague by vanquishing the Malak al-Maut - the Angel of Death. He feverishly insisted that he had stood face-to-face with Archangel Azrail, shadow blades grasped in their closed palms, whilst the souls of the damned and the unworthy were dragged into the underworld all around them. Fath had refused to move, and when Azrail reached for him, his shadowblade jerked upwards and cut towards him, only to cut through empty air. The Angel of Death was gone, and Fath was in his bed again.

A fantastic tale, but Fath had been surrounded by his physicians day and night, bedridden and barely conscious for weeks without end, so many simply attributed these crazed claims to be the rantings of a madman.

The quarantines instituted by the viziers began paying off, but outside Qadis, the Black Death reigned supreme. It reached its height late in 1280, when it stretched from Iberia to Russia, having already killed almost seventy million people.

That wasn’t enough to stop the peasants from rising up, however. Catholic minorities across al-Andalus blamed the carnage on Sultan Fath, convinced that God was punishing them all because of the tyrant king, and so they rose up in a large revolt in an attempt to overthrow him.

Ordinarily, such a revolt would be crushed with impunity, but the kingdom was still suffering under the yoke of the Black Death. Farms and cities all across the peninsula lay barren, so there was simply no hope of raising an army from the peasantry.

So Sultan Fath was forced to use his personal wealth to hire a Berber mercenary company, hailing from Morocco and numbering about 5000 veteran soldiers. He marched the mercenary army west and defeated the rebels in a short, decisive battle, before chasing down its remnants and crushing it altogether.

Unfortunately, mere days after one revolt ended another flared up, with heretic rebels vowing to execute Sultan Fath and install a Zikri Caliph in Qadis.

So Sultan Fath then marched his weakened mercenary force in the opposite direction to crush the Zikri as well, and after a short skirmish, the heretic rebels were also subdued.

With that, the next few months passed in relative peace, with no major revolts or rebellions breaking out. Slowly but surely, the Black Death retreated from the peninsula, only surrendering its hold on a town or city when there was nobody left to kill.

What it left was nothing less than chaos, however. All across al-Andalus, unfortunate children were made orphans in a harsh world, entire families were simply wiped off the face of the earth, and disease-ridden corpses were piled into mass graves.

This would not be easy to deal with, especially with the Majlis being as uncooperative as it was. The powerful Andalusi emirs blamed Sultan Fath for the catastrophe, claiming that it was his idiocy in assassinating viziers that left al-Andalus so unprepared for the plague.

Sultan Fath knew that he needed to gain the favour of the Majlis, they were powerful and they were angry, and they would undoubtedly oust him if they so desired.

Another year trudged past slowly, this time consisting of recovery and reconstruction, as rulers all across Europe tried to stabilise their realms. At the turn of 1286, however, Sultan Fath was finally presented with an opportunity to unite the Andalusi behind him.

The Kingdom of León-Aragon erupted into a civil war late in December, and what was the best way to unite the nobility than through a common enemy? It had worked for Sultan Hakam, and Fath was sure that it would work for him too, or at the very least give him some breathing space.

So, in a short sermon, Sultan Fath declared war on the Leónese and raised a surprisingly large army. Fath was more of a commander than he was an administrator, however, so it wasn’t long before his budget was in the red once more.

For all his faults, Fath was an undeniably gifted warrior, and he led the Andalusi army as they captured several large fortresses lining the Mediterranean coast.

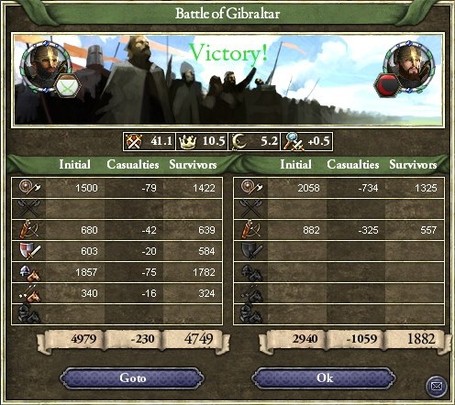

A small Christian army encroached on Andalusi-occupied territory in the summer of 1287, providing Fath with the perfect opportunity to pounce and wipe it out, which is exactly what he did…

… almost. He almost did it.

The small army proved to be nothing more than bait, and it was on the verge of collapsing before a massive second army stormed onto the battlefield, reinforcing the fight with another 12,000 Christians.

The numbers were fairly even, and for the next few hours the battle raged without end, neither side able to gain an advantage without losing it minutes later.

Eventually, however, the large numbers of fresh reinforcements proved too much for the tired, worn-down Andalusi lines. After a particularly vicious counter-attack, the Muslim army finally collapsed as soldiers broke rank and began fleeing, turning the battle into a rout.

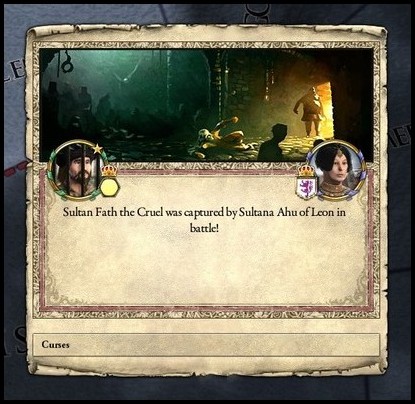

Even worse, the Leónese cavalry stormed the Andalusi pavilion to find Sultan Fath himself, disguised as a page in an attempt to escape unnoticed. Alas, it was not be, and the prestigious and all-powerful Sultan of al-Andalus was carted back to León in iron chains.

Imprisoned by his bitter enemies, Sultan Fath had no room to negotiate whatsoever, and he was forced to surrender and pay large amounts of tribute to Queen Ahu.

Fath returned to Qadis a broken man. He was the first Sultan to ever be captured in battle, so there were no words that could accurately describe the humiliation he felt as he entered the city gates, surrounded by his guardsmen and retainers, who held back the jeering crowds.

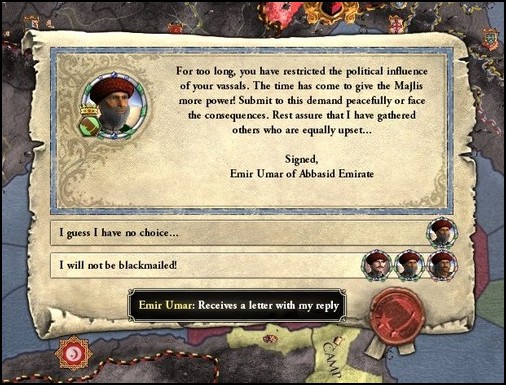

And it would not end there. The Majlis were furious, claiming that all of al-Andalus suffered because of Fath’s foolishness. A faction within the Majlis - this time led by Umar of the Abaddid Emirate - demanded that compensation be paid, in the form of drastic laws that would further limit the Sultan’s powers.

The Majlis were not authorised to have anything greater than advisory roles, an enraged Sultan Fath declared, before refusing their attempts to restrict his authority.

This, of course, was not the answer the'd been hoping for.

Almost every emir who had a seat on the Majlis rose up in revolt, coming together in a powerful league, united by their common hatred of Fath. Only the Aftasids and the Banu Musa (descendents of Grand Vizier Musa) remained loyal, pledging their levies and coin to the loyalist cause.

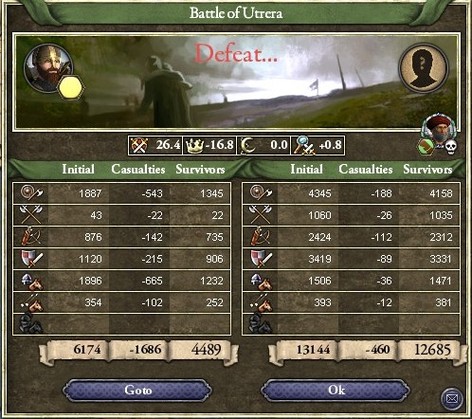

With the Leónese defeat closely following the devastating Black Death, however, Sultan Fath was only able to raise 6000 men - less than a third the size of his enemies’ armies.

Fath attempted to lead his small army westward, where he could plan out a strategy, but he was pinned down at Ishbiliya by a 12,000-strong rebel army. Predictably, with such superior numbers, the battle ended in crushing defeat for Fath’s forces.

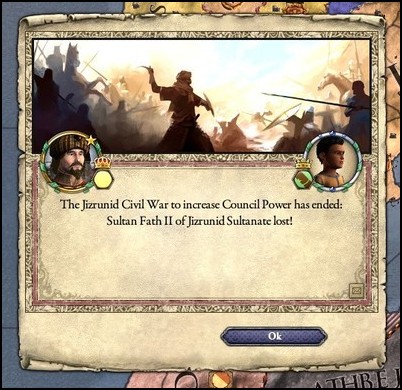

The rebels chased down the loyalist army and defeated it in another engagement near Al-Gharb, which is where Sultan Fath surrendered yet again, utterly dejected.

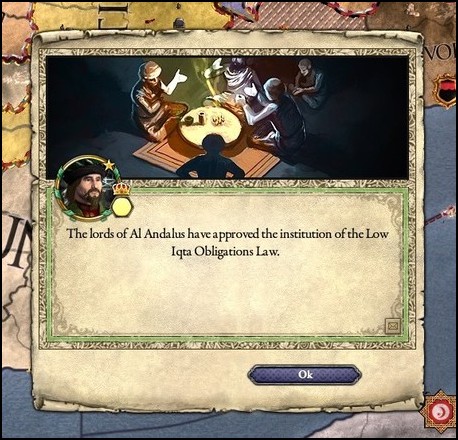

In addition to eased taxes and levy obligations, the rebels instituted a law that made it mandatory for any Sultan to consult the Majlis before declaring war. It was not too harsh, perhaps because the lords of the Majlis understood just how unstable al-Andalus was, time was needed for the broken kingdom to recover.

Sultan Fath II returned to Qadis in humiliation yet again, but his woes were not yet at an end. Apparently, there were several sheikhs who wanted to depose Fath altogether, bent on installing one his numerous cousins - Ali ibn Hakam - to the throne in his place. This faction was led by Yahaff, the Emir of Balansiyyah, a powerful aristocrat in his own right...

And Fath, well, Fath reacted in the only way he knew how:

Whilst his spies ironed out plans to assassinate Emir Yahaff, Fath began enjoying life again, indulging in the pleasures of alcohol and women.

He had vastly underestimated the Majlis yet again, however, and for the last time.

No doubt masterminded by yet another faction within the Majlis, Sultan Fath II was assassinated late in 1288, poisoned by his precious wine.

His reign amounted to nothing but misery for everyone involved, with the Black Death and his disastrous war forever besmirching his already-tattered legacy, so the news of Sultan Fath’s death is met with a sigh of relief across all Iberia. The Sultanate of al-Andalus thus passes to his only living son, Ayyub, who is left to be raised by the Majlis.

edit; Bonus black death: