Part 21: The Victorious Sultan

Chapter 21 – The Victorious Sultan – 1305 to 1320Ayyub had been Sultan of al-Andalus for just five years, but five years was all he needed to make a lasting impression in the kingdom, leading the Mubazirun into victory after victory as Christian powers across the Mediterranean were humiliated.

As far as we know, however, Ayyub didn’t do it for the glory or prestige. We know him as a man of war, but his reasons for actually going to battle are murky and dubious, and many have speculated that he may have killed for the sake of killing.

Those are questions best left to philosophers, however. Whatever his reasons, whatever his ambitions were, Sultan Ayyub was determined to see them realised through force of arms.

Early in 1306, after a short period of respite, Ayyub finished what he started by declaring war on the Count of Arborea for the second time. He sent a small force to quickly quash any opposition and take Cagliari, bringing the war to an end within a month.

However, in an unusual occurrence, Ayyub didn’t personally involve himself in the war. He had far loftier goals in mind, goals that demanded time and attention, and goals that would reap far greater rewards.

Half a year after the conquest of Cagliari, Ayyub’s efforts were revealed when he convened an emergency session of the Majlis al-Shura, solely to request the authority to initiate another large-scale holy war. After paying off a few nobles and intimidating the rest, Ayyub got what he wanted, and messengers were on the road to Castille within hours.

Toledo was one of the richest and most important cities in the Iberian peninsula, with its central positioning placing it at the crossroads of a dozen trade routes, as well as making it a strategically-vital fort. It had been conquered by the Christian powers almost two centuries past, during the first wave of Reconquista wars, and has since been massively expanded and fortified by different kings. All of this fuelled the population growth so that, by 1307, it was by far the largest city in Christian Iberia.

Sultan Ayyub had obviously been planning an offensive to capture Toledo for quite some time, because two enormous Andalusi armies catapulted towards the city within days of declaring war, intent on seizing it before the Christians could raise an allied force.

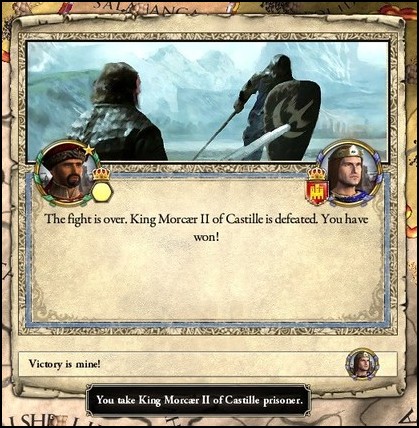

King Morcaer proved to be an adaptable man, however, and he managed to throw together an army before Ayyub reached Toledo. The two armies clashed just beyond the city’s walls, and in one of the bloodiest battles to date, the Andalusi managed to rout the opposing army.

The fighting had been costly, with almost 20,000 corpses littering the field by the end of the day. To Ayyub, however, every life sacrificed had been worth it, because King Morcaer himself had been cornered and disarmed in the heat of the battle.

In another surprising twist, however, Ayyub decided to spare Morcaer’s life. Perhaps the Sultan knew that a prisoner was more valuable than a dead body, or maybe he saw it as a way of ending the war sooner; whatever the reason, Morcaer was treated with the utmost respect by Ayyub, as befit his rank and name.

The Andalusi army then spread out and began capturing cities and besieging fortresses. With the capture of Morcaer, however, the war had essentially come to an end, it was just a matter of ironing out the terms for peace.

In return for his freedom, the Castilian king was forced to cede a vast stretch of land, including Toledo itself. Some contemporaries say that the king also offered his daughter in marriage to Ayyub - to cement a permanent peace between their two kingdoms - and insist that the Sultan accepted and took her into his bed, only to abandon her upon the treaty's conclusion. The nights they spent together would have consequences, however, and the young princess later birthed a bastard son - Ayyub's bastard, according to the tales.

Nonetheless, the victory once again pushed the frontiers of the sultanate outward, and al-Andalus was gradually nearing its greatest historical extent, as it was under the Umayyad Caliphate.

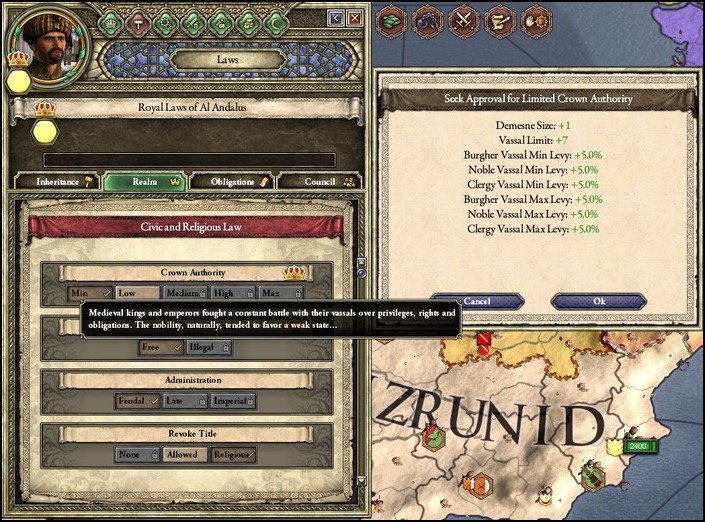

More importantly, however, the victory also gave Ayyub an incredible amount of influence. He divided to govern Toledo as part of the royal demense, but their were still rich pickings and fertile lands to be in the environs of the city, and everyone wanted a slice of the riches, with viziers and nobles began clamouring to earn the Sultan’s favour.

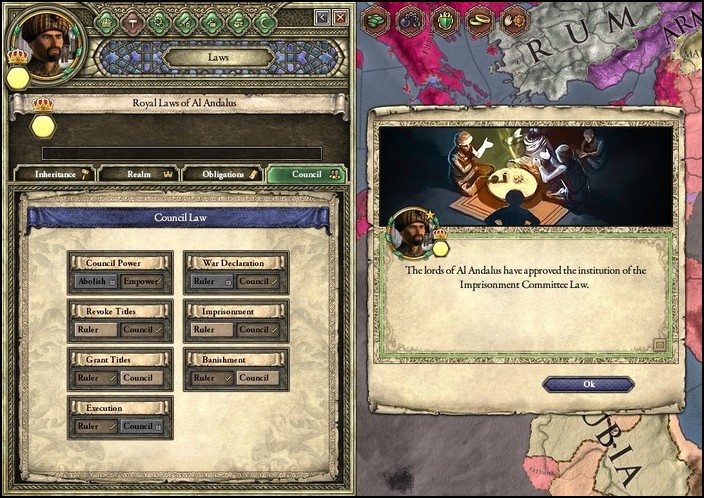

Ayyub used this newfound power to further centralise al-Andalus, passing reforms for the first time since the days of Sultan Hakam.

At the behest of the Majlis, Sultan Ayyub also agreed to mint a new currency of gold dinars, bearing his name and likeness, to commemorate his great victory over the Christian principalities.

Whilst Ayyub busied himself in Qadis, however, a war was raging further south. The ancient alliance between the Jizrunids and Almoravids had slowly eroded with time, with the Moroccan sultans gradually shifting their attention to from Iberia to West Africa, where lucrative riches dwelt. After a disastrous raid into Ghanan territory, however, war erupted between the African kingdom and the Moroccan sultanate, and it did not end as one might have expected.

After decisively defeating Almoravid forces on the battlefield, Mansa Samsou-Béri marched into Marrakesh with his army and declared himself the new sultan, uniting the two realms under his rule.

Dozens of Almoravid princes fled across the straits and into Qadis, where Sultan Ayyub granted them safe haven, refusing to clap them in chains when Mansa Samsou demanded their return. So the king of Ghana immediately took an aggressive stance against the Jizrunid kingdom, whom he saw as natural enemies anyways, and expelled Andalusi diplomats and advisors from Marrakesh. Many viziers and lords on the Majlis began calling for war against the Mansa, chiefly to restore the Almoravids, but Sultan Ayyub refused to do anything of the sort, too focused on his own plans.

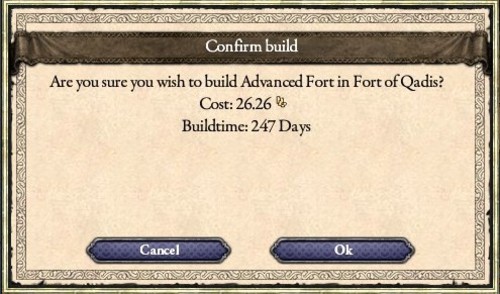

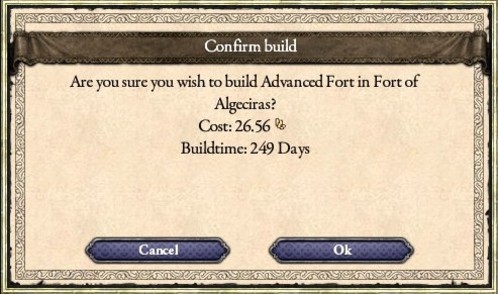

To try and ease the fear of an invasion, however, Ayyub did agree to finance the construction of new forts along the southern coast of Qadis and Algeziras.

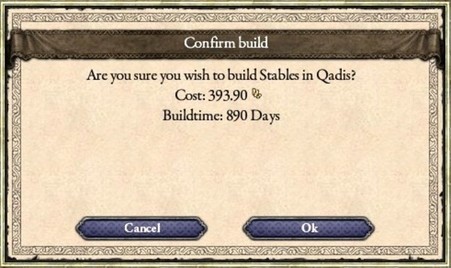

Whilst these fortifications were impressive, Ayyub only invested as much as he needed to. He preferred to sink his gold into his retinue instead, significantly expanding the Mubazirun and constructing several new barracks and stables to support its growing ranks.

Fortunately, the next few years crept past in relative peace. Ayyub finally managed to dedicate some time to his wives, fathering a string of sons and daughters - this time legitimate. Their upbringing was left to their mothers and servants, however, the Sultan was far too busy developing his retinue, ensuring that it remained a highly-disciplined force, obedient only to the crown. According to contemporary chroniclers, he would often train alongside his soldiers, developing strong bonds between himself and his guards.

In the summer of 1312, however, the drums of war began beating once more as rumours of another conflict spread.

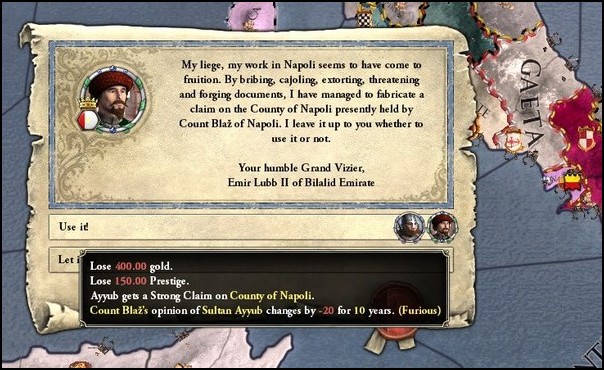

And indeed, Ayyub began rousing his vassals and summoning his banners once again, this time denouncing the free city of Naples. According to the Sultan, the Count of Napoli had conducted severals raids into Andalusi-controlled Cagliari, and such an insult could only be repaid in blood.

Sultan Ayyub managed to put together another huge army, this time numbering 30,000 levies, and led it towards Naples by sea. The Andalusi quickly seized control of Neapolitan beaches and, after overcoming the pitiful resistance, stormed Napoli itself.

Once Naples was firmly under his control, Ayyub adopted defensive tactics and began fortifying the city, preparing for retaliation. He expected German and East Roman expeditionary forces to arrive within weeks, but to his great surprise, the weeks turned into months and nothing turned up.

It didn’t take long for Ayyub to figure out why the Christian world wasn’t pouncing on him, however. Apparently, just as Naples succumbed to the Andalusi, the enmity between the Holy Roman Emperor and the East Roman Basileus had flared up into outright war.

The war was just another front in the constant German-Greek conflict for influence in Italy, but with the world’s two greatest powers suddenly at each other’s throats, one might’ve taken a step back and maintain neutrality. Not the sultan of al-Andalus, however, Ayyub saw only opportunity, and with the Basileus bogged down in a war, this was undoubtedly the opportunity of a lifetime.

Sultan Ayyub rushed back to Qadis to request permission for another holy war. The Majlis was made up of some of the most ruthless and ambitious men in all of al-Andalus, however, and they refused to grant Ayyub their blessing without receiving something in return.

Ayyub conceded, desperate to do whatever it took, and agreed to sign a law giving the Majlis further powers. In return, the estate-holders granted the Sultan permission to go to war again, this time against the full might of the East Roman Empire. Furthermore, the landed nobility vowed to contribute a greater percentage of their levies to the war effort, swelling Andalusi numbers.

Thus, just as 1315 began to dawn, the largest Andalusi army ever assembled made their landing at Napoli. Amounting to more than fifty thousand men, Sultan Ayyub immediately took command of the army and rushed headfirst into battle, eager to land the first blow.

The Battle of Siponto, a historic meeting, was the first engagement between al-Andalus and the East Roman Empire. Ayyub utilised his elite Mubazirun to deal tremendous damage to the enemy flanks, and after thick fighting raged for a couple hours, Greek commanders were forced to fall back and retreat.

Buoyed by their first victory, the Andalusi army began assaulting nearby forts, hoping to capture them before the Basileus could recover. The Romans were not known for their meekness, however, and another Greek army rushed forwards to engage the Andalusi just a month after their loss.

And this time, when the sun set on another battle, the celebrations were raging in Roman camps.

With the broken Andalusi army in full retreat, Sultan Ayyub led his army to engage the Roman force whilst it was still recovering. Outnumbered and tired, the Orthodox Christians failed to repel or adapt to Ayyub’s battlefield tactics, and they folded to the Sultan for the second time.

The Andalusi chased down the retreating enemy army and, in another short battle, utterly crushed what was left of it. With the rest of the Empire’s forces tied down in Northern Italy, the Andalusi levies spread out and began sieging down fortresses, capturing several over the next few weeks.

Before long, almost all of Lukania was under Andalusi occupation, but Basileus Andreas still refused to treat with the Sultan. The war in Italy was turning against Constantinople, but another large army was shifted from the northern front and sent to destroy the Andalusi army.

After landing at a Sicilian harbor, the Christian army rushed to engage Sultan Ayyub’s army, hoping to catch him by surprise.

And, to their benefit, the Andalusi were indeed caught unawares. Ayyub scrambled to throw together a defense, and when his chaotic lines quickly began crumbling to the Romans, he led a dangerous foray directly into enemy ranks. Inspired by their Sultan's sheer madness, his men followed him into the suicidal charge, and thousands of frenzied Andalusi piled into Roman lines.

Against all odds, the mad charge was enough to stun the enemy commanders into indecision, and the tide of the battle turned in favour of Sultan Ayyub. After a series of rapid counter-attacks, Roman lines began to falter and break, and it wasn't much longer until they were in full retreat.

Ayyub was recognised for his monumental victory when, immediately after the battle, his men began chanting 'al-Mansur', or 'the Victorious.'

With that, the war in southern Italy turned decisively in favour of the Andalusi, who quickly solidified their hold on Lukania and Sicily. The Basileus sent several more armies, each one smaller than the last, only to have them crushed time and time again by the Andalusi.

By the dying days of 1319, East Roman forces were on the retreat in northern Italy as well, and Basileus Andreas was forced to peace out of one front or lose on both. He sent envoys to meet with the Andalusi Sultan, and after a half-a-dozen meetings, a peace treaty was eventually agreed upon.

According to the treaty, Sultan Ayyub would pull back his forces from Sicily, but would be allowed to keep Lukania and Naples, along with a few other small cities. Neither side was satisfied with the terms, but the war had been raging for five years, and both needed time and peace needed to recover.

So Sultan Ayyub attached his signature to the treaty and surrendered Sicily, but he knew that this would not be the end of the Andalusi-Roman Wars, not by a long shot.

Ayyub returns to Qadis nothing less than a living legend, and all across al-Andalus, celebrations and festivities are held in his honour. The imams thank Allah for their courageous sultan, the nobility shower him with gifts and congratulations, inspired poets scramble to pen down their latest masterpiece... To many contemporaries, it must’ve seemed as though Ayyub’s victories would know no end, that he would go on to become greater than his own heroes, greater than everyone's heroes...

Little do they know, however, that the tale of Sultan Ayyub is not a happy one.