Part 22: The Miserable Demise of Ayyub Jizrunid

Chapter 21 – The Miserable Demise of Ayyub Jizrunid – 1320 to 1333With the end of the First Andalusi-Roman War, which earned Sultan Ayyub his undying fame as a king-warrior, the power balance across the Mediterranean gradually began to shift against the Eastern Roman Empire. Basileus Andreas suddenly found himself facing enemies on every front, and after losing successive wars against the Uqaylids and the Armenian Sultanate, realised that he had as many foes within the Empire as he did outside.

Meanwhile, a continent away, the Occitan Empire was facing internal troubles of its own. After a lengthy period of Occitan dominance, the predominantly-French northerners rose up in revolt, vowing to overthrow the emperor and restore the Kingdom of France.

Back in Iberia, on the other hand, the different Muslim and Christian principalities were experiencing peace for the first time in decades. The conflict with the East Roman Empire had come at a high cost, leaving Jizrunid coffers straining, and the autonomous Taifas were all but demanding an end to the constant war.

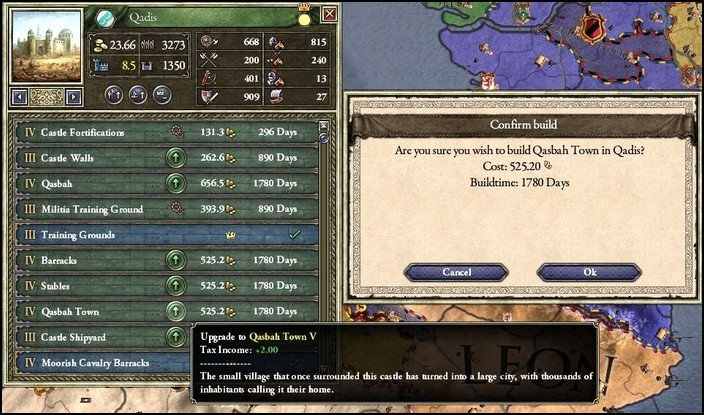

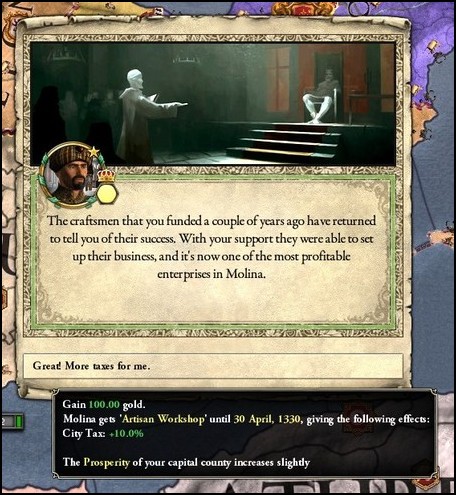

So Sultan Ayyub returned to Qadis – a place he detested – and started to actually rule for the first time in his life. He dispensed justice and amended the law, he appeased his vassals and hosted ceremonies, he financed businesses and expanded medinas.

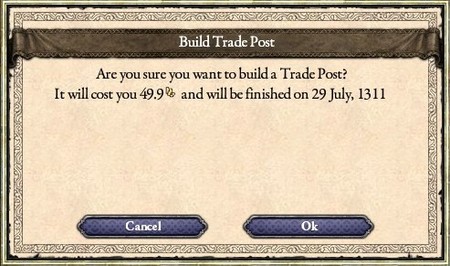

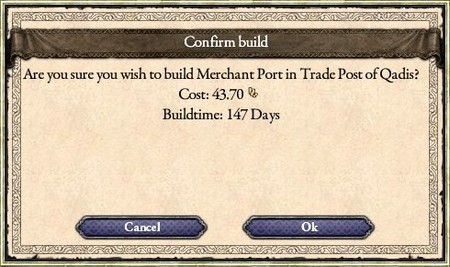

As the Andalusi Sultanate slowly recovered, taxes began to flow more freely and the income stabilised, and before long the gold began to pile. Even better, the coins he had minted - the gold dinar - had become the dominant currency in Iberia and parts of north Africa. Eager to encourage this, Ayyub dedicated large sums of money to construct trade posts and merchant hubs in Qadis, hoping to attract businesses and enterprises to the gradually-growing city.

The sultan also backed a number of newly-formed organisations, including a craftswork firm and a builders’ society, and used them to construct a plethora of mosques, libraries, baths, hospitals, gardens and other public works. Their most impressive endeavour would be the Marble Palace - one of the many Jizrunid palaces dotting Qadis, but this one was renowned for its crystalline walls and floors, for its streaked halls and chambers, for its polished busts and sculptures, all carved from the smooth mottled-white marble.

As the months stretched into years, Sultan Ayyub even began to take an interest in foreign shores. He had greedily read up on every book about Alexander the Great and other famed generals when he was just a boy, but as he re-read old classics, Ayyub realised that he had never truly considered just how far the Alexandrian Conquests had taken him.

Caught up in these dreams, Ayyub financed the travels of a certain Ibn Battuta, hailing from Tangier. Though the Sultan would not live to see Ibn Battuta return, the famed scholar would journey all across the Muslim world, documenting the many peoples and cultures from Al Andalus to Kilwa.

It wasn’t long before Qadis had once again been transformed into a vibrant hub of trade networks, Islamic culture and intellectual thought. Ayyub himself even learnt a few things during these calm years, not least of which included the importance of peace itself to the prosperity of any kingdom.

Nevertheless, Ayyub was still Ayyub, and he had always been a man of war. As he edged on almost a decade without swinging a blade or leading a charge, the sultan suddenly realised that he was fast becoming an old man, and declared his intent to go to war before the year was out.

And of course, for a man with Ayyub’s ambition, there could only be one target.

The Majlis did not oppose Ayyub’s decision, and once he announced it to his vassals and courtiers, emirs and sheikhs from all across Al Andalus flocked to join him on the holy war. Everyone still remembered the glories of the First Andalusi-Roman War, the poets still sung of al-Mansur’s dazzling battlefield victories, so they all wanted a share of the second.

Thus, when Sultan Ayyub landed at Amalfi about two years later, he did so with the largest Andalusi host every gathered. In a sweeping manoeuvre, a mind-boggling 70,000 men swarming across the border and into southern Italy, assaulting forts and sacking cities. The first Roman army sent to confront them was easily routed, and once the battle came to an end, almost every man had either been killed or captured.

The East Roman Empire was obviously in a state in decline, with Basileus Andreas struggling to throw together an army that could match even half of what Sultan Ayyub had, and his rebellious vassals were not helping. Even as he begged his various duces to contribute some of their own forces to the Empire's defense, the Andalusi were scaling and capturing dozens of castles and fortresses, quickly bringing Calabria under their occupation.

The second army sent from Constantinople fared little better than the first, routed after only an hour of fighting, only to be massacred in their thousands as they fled the blood-drenched field of battle.

At this point, as the end of another decade approached, it was looking as though Sultan Ayyub and his gigantic army were unstoppable. And with good reason – he had already crushed East Rome in two separate engagements, and looked poised to roll over the rest of her Italian possessions with ease.

The world works in the strangest of ways, however. Threads interconnect every single being on this planet, and as the Almighty pulls on one string, he tugs at another. Such is the case with Sultan Ayyub – and the outbreak of the Italian Revolt.

The revolt itself wasn’t a problem, numbering a measly four thousand peasants and farmers. Ayyub skimmed off a few men from his vast host and, leading the force himself, sailed from Napoli to suppress it within a month. It took two more months to track down the guerilla force and, in a bloody skirmish, destroy it.

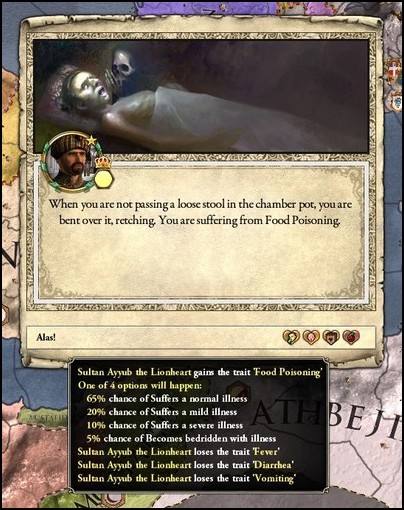

Shortly after executing the rebel leaders and putting their heads up for display, Ayyub fell back to Cagliari and prepared for his return to Italy, giving his men two days of respite. During these two days, however, the Sultan was accidentally served spoiled food, and he began feeling uneasy within hours.

The symptoms were not terrible, but his childhood stories of Alexander were still fresh in his mind, especially that of the warrior's grisly end. Alarmed and unnerved, Ayyub immediately summoned local physicians, if only to ensure that his illness would soon pass.

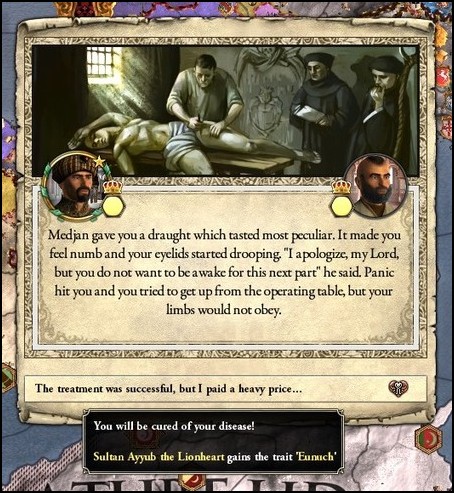

That was not to be. The physicians declared the Sultan’s affliction to be nothing other than dysentery, and unless treated immediately, it would be fatal. Panicked, Ayyub agreed – but the operation did not go as expected...

Castrated. He was castrated. To cure food poisoning.

Historians have theorised that the physicians were Sardinian partisans themselves, and took the opportunity to fatally wound the Sultan. Whatever the reason, after waking from the operation and realising what had happened, a shell-shocked Ayyub abandoned his campaign and rushed back to Qadis.

Confused and unsure, Ayyub's secondborn son - Raf - took control of the Andalusi levies in Italy, but he quickly began suffering costly defeats without his father's expertise and leadership.

Unfortunately, this was not the best time to return to Al Andalus. In north Africa, a devastating war had once again erupted between Morocco and Ghana, with an Almoravid claimant named Tacfin leading the rebellion against the West Africans. After a violent civil war, Mansa Samsou and his armies were pushed back to Ghana proper, and the Almoravids emerged independent once more.

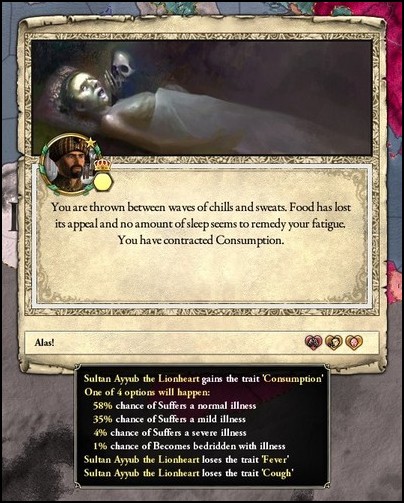

The war, as large-scale conflict tends to do, also facilitated the spread of disease. Consumption thrived as armies clashed up and down Morocco, and after infecting Andalusi merchants, it made its way up to Qadis and thus Iberia.

A traumatised Sultan Ayyub arrived at at the capital just as the disease broke, infecting thousands within weeks, catching both peasant and noble unawares. The Sultan holed himself up inside the Marble Palace, but even that would not save him, with Ayyub coughing up mucus and blood just days later.

Stripped of his manhood, suffering through racking coughs and unable to leave his sickbed, the all-powerful Sultan of Al Andalus was utterly broken, sealing off his palaces and refusing to see anyone. His own family was denied entry by his loyal guards – the Mubazirun – only fuelling the spread of rumours throughout the Qadisian court.

High-ranking members of the Majlis managed to force their way into his rooms days later, far too late, to find Ayyub cold and unbreathing.

And thus ends the tale of Sultan Ayyub al-Mansur. Undeniably one of the greatest Jizrunid Sultans, Ayyub will live on in history as he who stood at the apex of the world and smote down any whom he named enemy, only to be brought low by a scalpel.

Sultan Ayyub’s firstborn son and heir, Ali, is crowned as his successor in an extravagant ceremony a month later. There are high hopes for the talented youngster, but while there are very few who will ever match the feats of Ayyub, the Mad King is certainly not amongst them.