Part 24: Dynastic Squabbles

Chapter 24 – Dynastic Squabbles – 1348 to 1375As months become years, years become decades, and decades become centuries, memories fade and old wounds are forgotten. Such is the case with Sultan Ali, the Mad King, whose life would be spun into a thousand conflicting legends in the years following his death. The one legacy he truly left, however, was chaos.

Sultan Ali's reign had been short and bloody, he’d somehow managed to alienate his closest allies and anger his most powerful enemies in less than a decade, slaughtering thousands and devastating Al Andalus as he did so. His bastard half-brother and killer would crown himself King of Aragon, seizing Zaragoza as his seat and marrying into surrounding kingdoms, thus placing another formidable rival on Andalusi borders. And as if that weren't enough, the angered clergy were already up in arms, starving peasants were rioting, and the powerful nobility were openly preparing for rebellion.

This is Sultan Ayyub II comes into play. Despite the widespread hate of the royal dynasty, some of the most powerful titles and richest lands were still ruled by Jizrunids. Ayyub himself had ruled vast estates around Tulaytullah for many years before becoming sultan, but it was only as Al Andalus was beginning to collapse that he was invited to Qadis to succeed Sultan Ali.

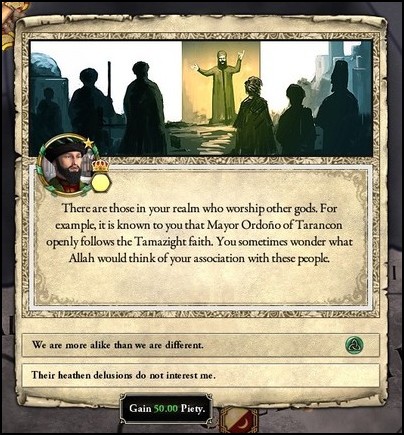

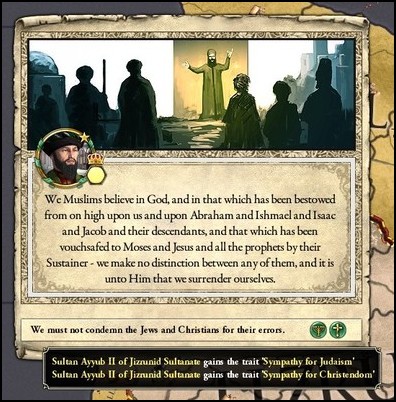

Of course, the first thing Ayyub did was denounce the pagan ways of his father, claiming that Ali was nothing more than a diseased lunatic with a crown.

That wasn’t enough to satisfy most of the entrenched nobility, however. Many detested Ayyub for nothing more than the fact that he was Ali’s son, and openly demanded an end to the Jizrunid line altogether, claiming that the entire family was ‘tainted by Shaitan’.

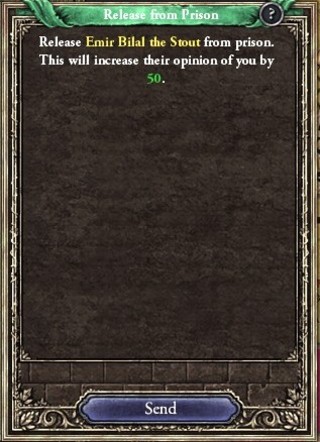

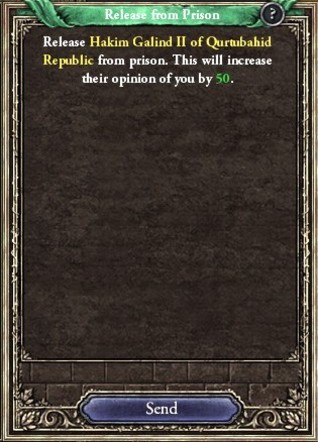

The anger of the ulema, the ongoing peasant riots and the rebellious Taifas all meant that Al Andalus was on the verge of imploding. In an effort to repair relations with his vassals, Ayyub released dozens of prisoners who’d been chained by the Mad Sultan, without ransom.

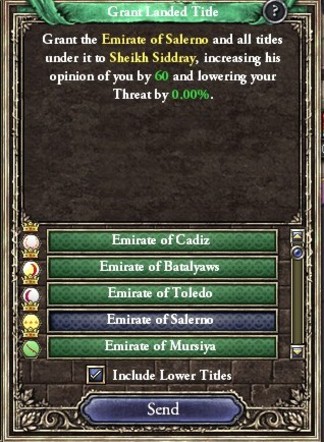

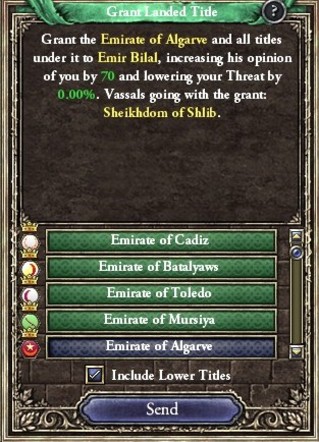

He even bestowed titles and land grants to the nobility, hoping to placate his furious vassals.

Nothing proved to be enough, however. Sultan Ali’s reign of terror had seen countless nobles imprisoned and executed, it had seen the traditional Sunni elite humiliated and persecuted, it had seen the poor and the weak extorted without mercy. These wounds would take years to heal, years that Sultan Ayyub II did not have.

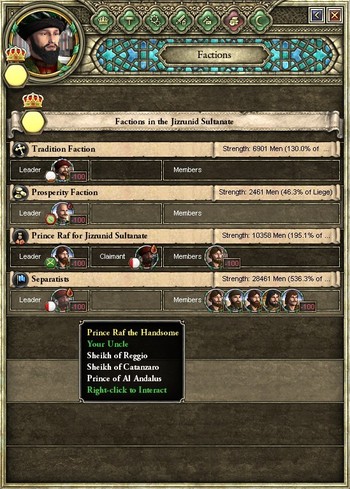

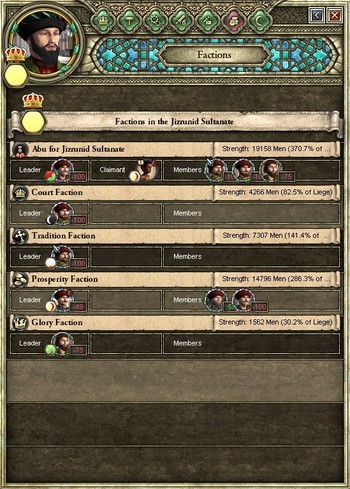

Ayyub did manage to keep a firm hold on his personal demesne, which included the Emirates of Qadis and Tulaytullah (or Toledo, as the Christians call it), so he wasn’t without influence. The nobility would not be denied, however, and a powerful separatist league eventually emerged - led by Ayyub’s own uncle, Raf .

Raf ruled vast lands in southern Italy, from where he watched his brother descend into madness and civil war from afar. Upon the death of the Mad Sultan, the Majlis invited him to take the throne, but he refused the poisoned offer without hesitation. His place was in Italy, where he had carved out a kingdom of his own.

And now, it was time to seize his crown. Refusing to be ruled by his nephew from Qadis, Raf declared independence from Al Andalus, along with a smattering of emirs and sheikhs in Iberia.

As usual, the war played across the width of the peninsula, centering around Qadis and Qurtubah. Even the emirs and sheikhs who hadn't rebelled refused to help the Sultan, formally adopting a neutral stance, so Ayyub could only scrounge together 8000 levies. His enemies, on the other hand, managed to raise a host that stood 30,000 strong, massively outnumbering the meagre loyalist forces.

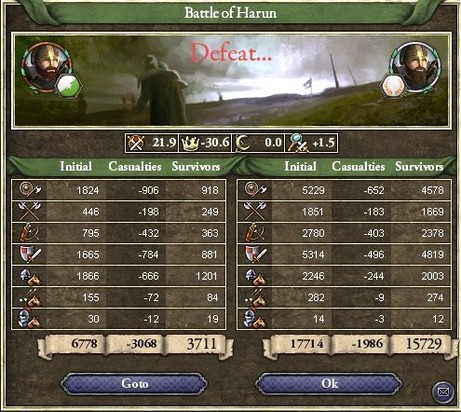

One of the many rebel armies, numbering about 12,000 troops, pinned down Ayyub’s small army near the fortress of Ishbiliya. The rebels lost hundreds whilst crossing a flooded river, but they still greatly outnumbered Ayyub’s forces, which were quickly surrounded and routed in a short battle.

The loyalists fled westward, towards Shlib, for respite. Another rebel force pursued them, however, and the two armies clashed again near Mérola.

Sultan Ayyub’s army initially had the upper hand, throwing the 6000-strong rebel force back, but the enemy were quickly reinforced with another 10,000 seasoned, well-rested soldiers. Facing hopeless odds, the demoralised loyalists melted without putting up much more opposition, and the rebels scored another decisive victory.

With his army demolished, the civil war took a sharp turn for the worst, forcing Sultan Ayyub to flee back to Qadis. Already saddled with heavy losses and unable to raise another army, Ayyub was forced to watch from his balconies as the powerful fortresses at Qurtubah, Granada and Tulaytullah all fell over the next few months.

Once the rebels had a firm hold on central Iberia, they began the march to Qadis, by far the best-fortified city on the peninsula. It would have been able to withstand a siege for at least a year, but Sultan Ayyub knew that there was little hope of somehow winning the war, so he instead agreed to meet with the rebels, who were demanding nothing less than full independence from Al Andalus.

Ayyub could only submit.

And the results were not pretty.

The Aftasids had managed to carve out a sizeable kingdom, ruled from their seat in Batalyaws, but it was nothing compared to the sultanates of their forefathers. The newly-independent domains of the Bilalid dynasty, meanwhile, were scattered across Iberia. A small stretch of land in Shlib was also granted independence, ruled by some minor lord. And lastly, across the Mediterranean, Raf Jizrunid crowned himself Emir of Lukania.

That said, the peace treaty had left most of the Jizrunid kingdom largely intact, but after years of civil conflict and war, it was by far the weakest of the Iberian powers. Ayyub didn't care much, however, he was simply glad to have the war at an end, so that the reconstruction his kingdom sorely needed could finally begin.

Unfortunately for him, however, opportunists were standing ready to pounce on the bloody carcass of Al Andalus.

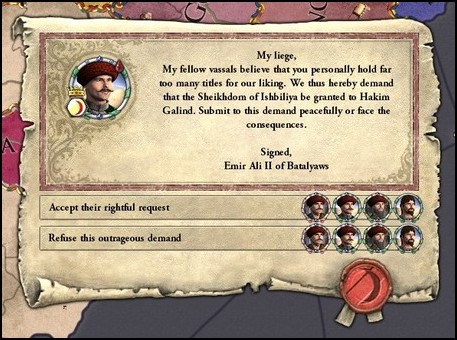

Mere weeks after the civil war had come to an end, a small faction within the Majlis approached Ayyub and demanded that he surrender Ishbiliya over to them, led by one Ali banu Musa (the direct descendent of the famous Grand Vizier Musa).

One of the richest and most populous cities in Iberia, Ayyub giving Ishbiliya up would mean surrendering a good chunk of his power, riches and influence to the Majlis. This would’ve left him with almost no leverage over his own vassals, so he obviously refused, plunging Al Andalus into yet another civil war.

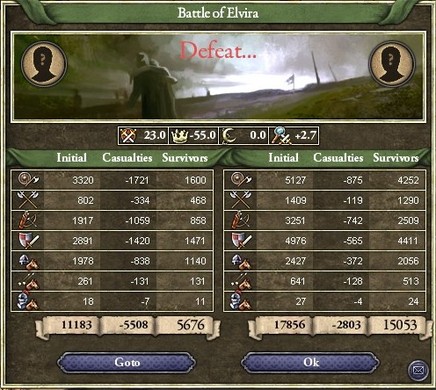

As usual, the rebels greatly outnumbered the loyalist forces, this time about two to one. An 18,000-strong army marched on Granada, where Ayyub’s levies were gathering, and annihilated the unprepared loyalists in an utter massacre.

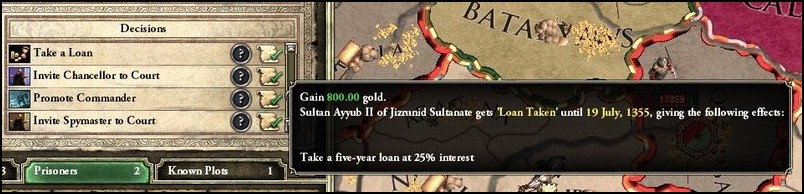

Ayyub retreated with what was left with his forces, but he couldn’t simply surrender, not again. Facing utter ruin, he turned to the Jewish community in Qadis, who agreed to loan him a small fortune in return for future favours.

The Sultan wasn't quick to spend the money, however. Instead, he hung back near Shlib and simply waited for any chance to counter attack. His opportunity arrived about a year later, when the rebels took massive losses trying to assault Tulaytullah, suffering almost 10,000 casualties. Sultan Ayyub chose this moment to strike back, raising a 5000-strong mercenary army and sweeping northward, towards Qurtubah.

This was enough to attract the attention of the rebels, who redirected their forces to extinguish the loyalist threat, marching on Ayyub's army with about 15,000 men.

This time, however, he was ready. Ayyub was no strategic mastermind, but a few tactical gambles proved enough to overcome the rebel's numerical superiority, after which they were quickly routed and chased off the field.

Ayyub was quick to capitalise on this much-needed victory, chasing down and crushing a smaller rebel force in a short skirmish.

With that, the loyalists could begin occupying enemy territory, sieging down and capturing several large fortresses in quick succession.

Once the enemy capital of Plasencia had fallen, the rebels finally agreed to put down their arms and surrender, bringing the civil war to an end.

The victory, though relatively minor, was enough for Ayyub to finally solidify his position as sultan. He spared the life of Ali banu Musa, but he also used his rebellion as an excuse to strip the lords of the Majlis of their autonomy, forcing them to submit to him, giving him more levies and more taxes.

Sultan Ayyub also began to chip away at the authority of the Majlis, forcing them to revoke an act that forbade the Sultan from dismissing anyone who had a seat.

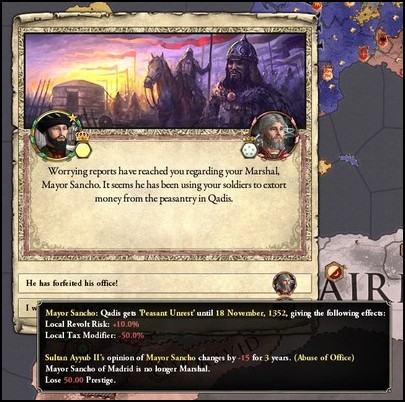

Ayyub didn’t simply empower himself for no good reason, however, he saw it as the only way of stitching a divided Al Andalus into a single entity once more. He used his newfound powers to dismiss the weak-willed and talentless, as well as crack down on corruption and nepotism, and instead began appointing councillors and viziers based on merit.

He also set up a court of law that had the authority to try nobles, allowing Ayyub to imprison and execute any naysayers for ‘treason’, as it were.

Very quickly, Ayyub began to gain a reputation as an honest and just man, a far cry from his father. He distrusted his own advisers (especially court physicians), but as the months turned into years, the relations between the Sultan and his vassals began to ease once more.

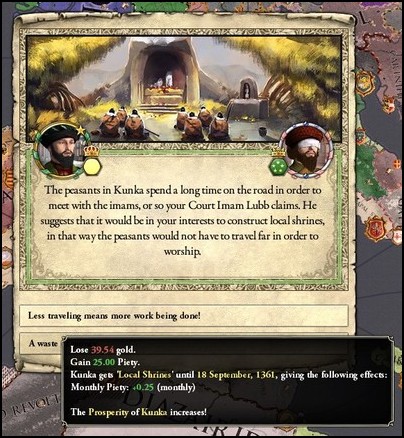

Ayyub even made concessions to the clergy, granting the ulema more authority in return for their loyalty. In return, a host of imams agreed to give sermons to the peasantry to try and rebuild support for the crown, thus legitimising his rule.

Whilst Ayyub dealt with the consequences of the Mad Sultan’s reign, however, the other powers of the Iberian peninsula were busy taking advantage of Andalusi disunity. Aragon - which was ruled by his bastard uncle, Cyneric - had conquered Barcelona and Tarrakhona, transforming it into a power to be reckoned with. And further west, Castille had expanded just as aggressively, waging successful holy wars against two taifas and reconquering a large chunk of Portugal for Christendom.

As far as Ayyub was concerned, the Castilians had conquered and occupied rightful Andalusi territory. He still wasn’t powerful enough to challenge the Christian powers, however, so the best he could do was wage war on the independent Taifas, starting with the Aftasids of Batalyaws.

Sultan Ayyub stayed in Qadis whilst his appointed commanders led the war effort, but he received daily reports as Andalusi levies marched to engage the rebels, clashing near the Christian-held city of Lisboa.

With about 20,000 experienced soldeirs, the Andalusi were easily able to overcome the Aftasid forces, routing and demolishing them in a single engagement.

With nothing to oppose them, Ayyub's forces were then free to capture large stretches of land from the independent taifa, seizing countless towns and cities.

As his army finally besieged Batalyaws, Sultan Ayyub sent envoys to treat with the Aftasid emir, offering him a very favourable deal. In return for swearing loyalty to Al Andalus and the Jizrunids once more, he would let the Emir continue to rule his domains, albeit as a mere vassal.

Facing no hope of actually winning the war, the Aftasid emir was quick to agree, thus bringing Batalyaws back into Al Andalus.

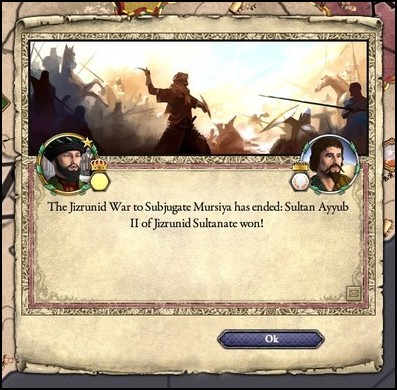

Sultan Ayyub didn’t dismiss his levies upon the conclusion of peace, however, instead directing the army towards Mursiya. Messengers were sent ahead, of course, carrying another declaration of war.

The Taifa of Mursiya was unable to put up even as much resistance as Batalyaws, weak as it was. Ayyub’s forces engaged and destroyed the emirate’s small army in a short battle, before turning towards the capital itself.

Mursiya surrendered just weeks later, after Ayyub offered Emir Hasan Bilalid the same deal as he had to the Aftasids of Batalyaws - forfeit your independence, or be crushed.

There was only one answer to that.

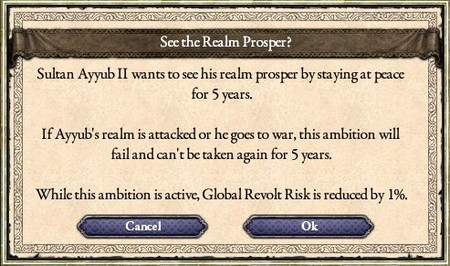

With that, most of Al Andalus was united under the Jizrunids once more, and Sultan Ayyub could begin focusing on internal matters. The Christians still held Portugal and Cyneric the Bastard ruled in Aragon, but Ayyub was more interested in recovery than more war, and instead vowed to see Al Andalus prosper in peace.

The next few years passed by slowly, but fruitfully. Once his loans were repaid, Ayyub began investing his personal income into the kingdom, repairing damaged roads and bridges, erecting shrines and stalls, constructing statues and monuments.

He also financed the development of towns well-placed to become centres of trade, building countless merchant ports, caravan hubs, and qasbah towns in an effort to spur prosperity.

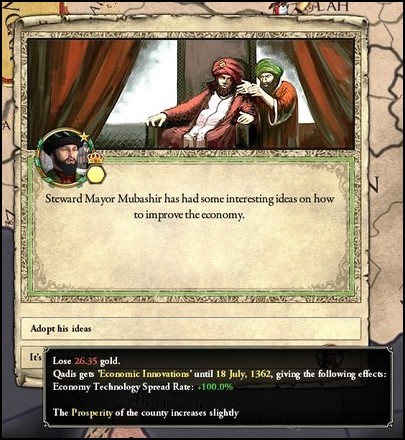

Ayyub was also one of the few Andalusi sultans who took a personal interest in the economy of his realm, educating himself on how best to increase his income without putting too much of a burden on his subjects.

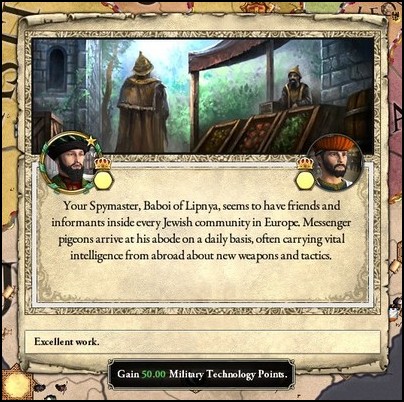

And to repay the Jewish communities for their support during the civil wars, Sultan Ayyub decided to revoke specific clauses of Utmani's Edict - namely, those that discriminated against Jewish language, customs and traditions. With full religious rights and freedoms granted to them, Ayyub personally employed and befriended countless Jews, using their widespread diaspora to fuel development within Al Andalus.

Ayyub even began rebuilding relations with the old allies of the Jizrunids: the Almoravids. He regularly sent diplomats and envoys laden with gifts to Marrakesh, and received the same, with a gradual friendship developing between Sultan Ayyub and Sultan Mazigh. Eventually, Ayyub offered to marry one of his daughters to Mazigh's son, an offer that was readily accepted, with the ceremony attended by both kings. Mazigh's son would eventually settle in an estuary along the Wadiana river, rich and fertile lands granted to him by Sultan Ayyub.

And with that, needless to say, a powerful alliance was forged between the two kingdoms.

Speaking of the marriage of his daughter, Ayyub certainly had children to spare. There is little doubt that the Sultan enjoyed the… finer things in life. In addition to developing a taste for expensive wines, Ayyub gained a bit of a reputation for his love affairs, dalliances and scandalous flings. Very odd, for a Jizrunid.

Eventually, all of those dalliances do add up, and each has its consequences.

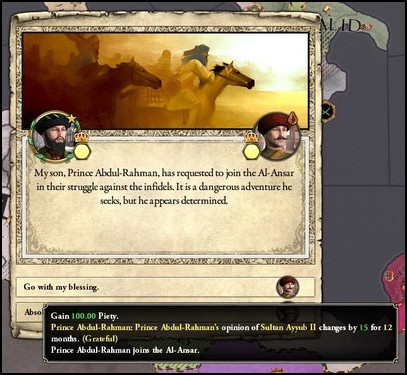

In another break with tradition, however, Ayyub also took great joy in raising his children, both the trueborn and the illegitimate. He encouraged his daughters to take up learning at the House of Knowledge, he approved of his firstborn’s fine eye for numbers and accounts, and even allowed a few of his sons to adventure abroad.

In fact, one of his sons even rose to become the Emir-ul-Mujahdeen of Al Ansar, a prominent order of Ghazis dedicated to fighting the Egyptian Crusaders. A particularly famous figure, both in history and the arts, Ma’n would dramatically alter the political landscape of the Near East and Iberia over the next few years.

Everything comes to an end, however, and peace is no exception. Whilst Sultan Ayyub was busy focusing on internal development, the Christians in the north had been clashing in short, sporadic succession wars. And as the end of another century gradually approached, León and Castille were united under a single king, Bérard.

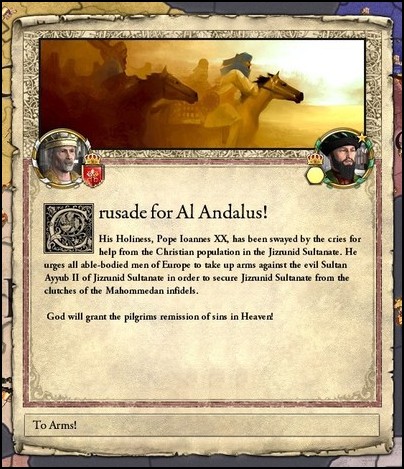

This dramatically altered the power balance of Iberia, but even before Sultan Ayyub could react, he received word that tens of thousands of crusaders were already marching towards Qadis, jostling one another under the hot sun, weighed down by steel and chain mail, eager to whet their blades in holy war.

The Third Crusade for Iberia has begun.

edit: It’s been another hundred years, so have another map. Don't rely on it too much though, things change quite a bit over the next couple years.

Also, a bit of extra information, as per request. It’s not everything, so if you want something in particular, let me know and I’ll try and get to it.

Jizrunid family tree in 1375:

Largest religions:

Largest realms:

Largest army: