Part 35: Pyrrhic Victory

Chapter 3 – Pyrrhic Victory – 1460 to 1474The new decade opened with the outbreak of a large rebellion in what was once Portugal, renamed al-Adna upon its conquest.

The rebels consisted mostly of untrained peasants and farmboys, so it took all of one day to quash it, with thousands of dead littering the streets after their defeat.

More importantly, back in Qadis, the nobility were quickly growing more corrupt. Emirs and sheikhs were given grants allowing them to tax their land more harshly, angering the merchants in the Majlis, who were hoping to use the money to expand their shipping.

This inevitably led to old family rivalries resurfacing, with the Aftasids and Abbadids arguing over every square inch of land, with the Yahaffids and Ghizvanni launching raids into Christian territories, with the Hakami and Hammudids feuding over the rights to this village or that town. Rather than risk the outbreak of rebellion, however, the incumbent Grand Vizier personally settled any arguments between the great houses of the Majlis.

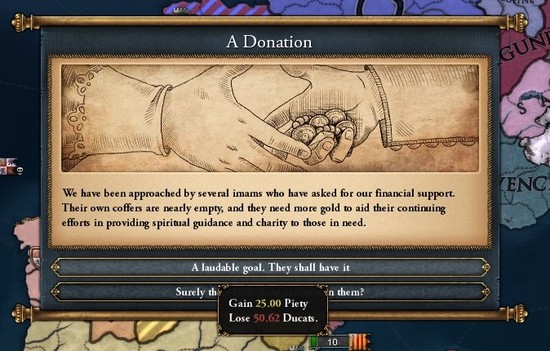

A rivalry was also brewing between the League of Merchants and the Ulema, unsurprisingly, over the matter of hiring foreign traders. The New Taifas eventually sided with the Merchants, always eager to rake in more money.

The Ulema were a powerful force in their own right, however, so a fair few donations soon made their way into the mosques, appeasing the imams for now.

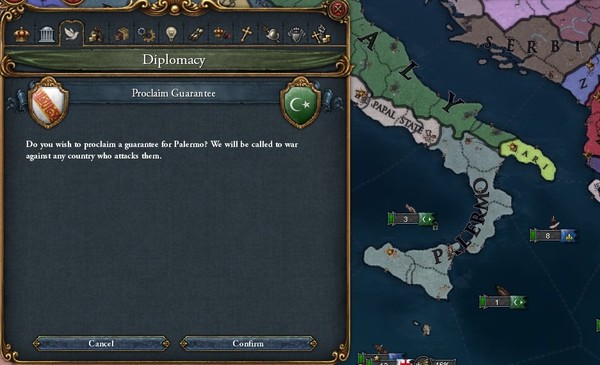

In fact, the Grand Vizier, who hailed from the old Hammudid family, was a particularly zealous man. He and the religious elite had not failed to notice the retreat of Islam all across the world, from the Levant to Italy, and he was determined to bring a halt to it.

To that end, he issued a guarantee of the Emirate of Palermo, which was under considerable threat from the Kingdom of Italy.

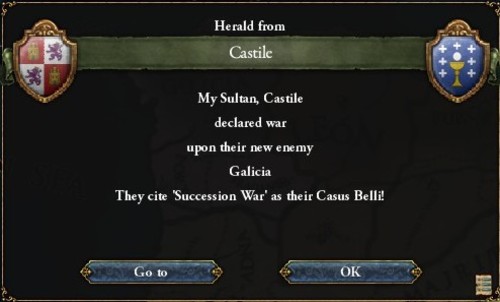

The attention of the Majlis soon turned back to the Iberian peninsula, however, with the outbreak of a succession crisis late in 1464. The King of Galicia had inherited the throne of León from a distant cousin, but the Castilian King Gundemaro refused to recognise it, instead claiming the throne himself.

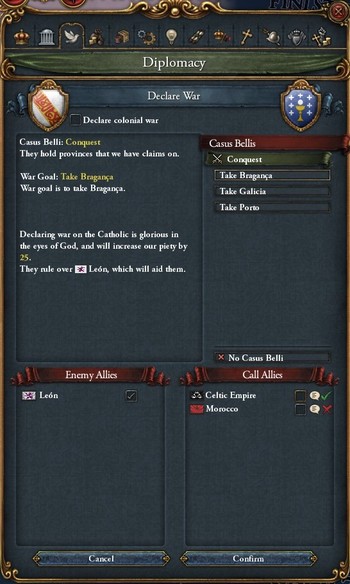

As always, the Taifas were eager to take advantage of the chaos, and began readying the army. As new recruits were armed and trained, the war in the north quickly turned against Castille, whose army had been destroyed in a single battle.

Castille was also allied to France, however, so the hawkish nobles turned to the far weaker Galicia instead. The army was finally ready by the end of 1466, when envoys were dispatched to Galicia, carrying a declaration of war.

The Andalusi flooded into Galicia and León unopposed, quickly bringing regional capitals to siege. A few weeks later, Castille managed to defeat Galicia in another engagement, sending the shattered army westward, where the Andalusi waited.

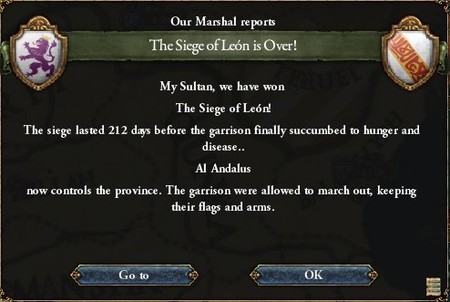

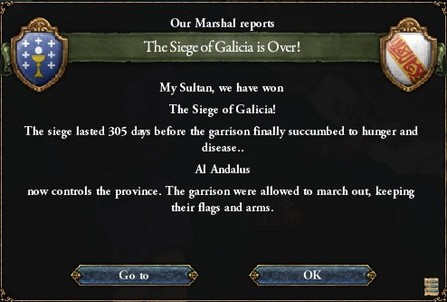

With the Galician army wiped out, the Muslims began spreading out, putting castles to siege and towns to the torch.

By the end of the year, the starving Galician masses capitulated, with the garrisons of both León and Galicia surrendering unconditionally.

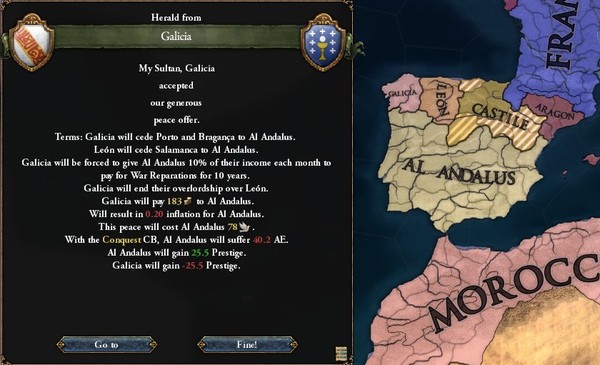

The Christians, eager for peace, agreed to the demands of the Majlis without negotiation, and the war ended with the surrender of Porto, Bragança and Salamanca, as well as large amounts of tribute.

Upon hearing news of the Andalusi peace, King Alfonso of Castille furiously denounced the Andalusi as belligerent warmongers, to pick just one from a long list of unsavoury insults.

And he wasn’t the only one enraged with the rapid expansion of Al Andalus, with most neighbouring countries now considering defensive pacts, if only to stave off the inevitably Andalusi invasion.

And it isn’t surprising to see why, the past twenty years have seen the loss of some the richest, most populous cities to the Muslims, a significant blow to all of Christian Iberia.

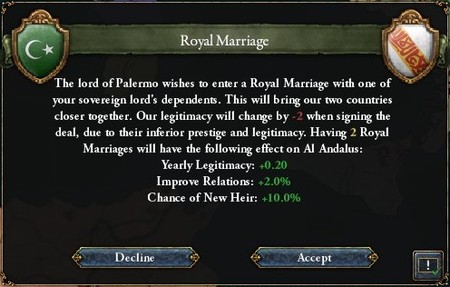

The Majlis simply discarded any warnings or insults, however, convinced of their own invincibility. The focus turned inward once more when officials arrived from the Emirate of Palermo, hoping to arrange a marriage between the Sultan's brother and a Sicilian princess.

A good match, the proposal was agreed to, binding the two branches of the Jizrunid dynasty closer together.

Speaking of distant shores, North Africa spent the past few years embroiled down in war, with Algiers falling to the Izri Emirate, the Izri falling to Tunis, and Tunis falling to Morocco and Egypt.

The Balkans have been similarly drenched in blood, with the resurgent Latin Empire cut down to the size by an alliance of Greek minors.

In the Near East, meanwhile, Armenia has been steadily pushed back by Nicaea and the Fatimid Caliphate, whilst the Azeri-Nurradin alliance was decisively defeated in a war with Persia.

Back in Qadis, the League of Merchants loudly decried the aggression of the Taifas in an assembly of the Majlis al-Shura, warning that it could well lead to another crusade against Al Andalus.

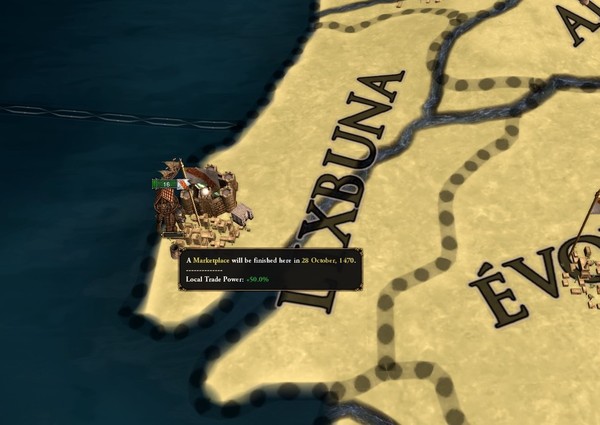

Instead, the Merchants have been focusing on the construction of a sprawling marketplace in Lishbuna, hoping to attract the alienated Christian merchants into reviving trade with them.

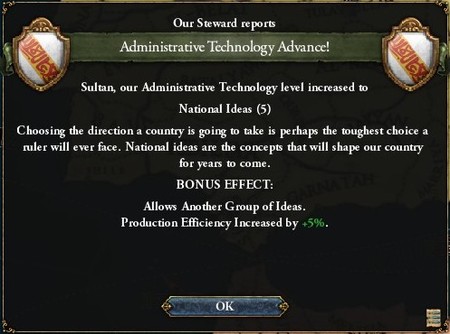

The Ulama, meanwhile, have been busy reorganising the administration in Qadis. Before long, a good deal of high-ranking officials consisted of the clergy, all educated and trained in the House of Knowledge.

This quickly proved to be very beneficial to Qadis, which saw a sudden explosion in population through the 1470s, which in turn led to a rise in production and taxation.

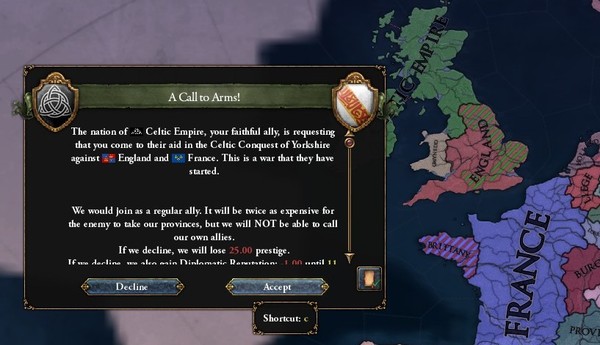

The New Taifas, however, weren't as interested in trade or development. Their attention was fixed in the north, where border raids triggered the outbreak of another war between the Celtic Empire and England.

The Celts quickly overwhelmed the sparse English defenses and were well on their way to London before long, but then the French King Adrien decided to intervene, worried at the prospect of a unified British Isles.

France invaded and captured large parts of Brittany - the junior personal union partner of the Celtic Empire - and with that, the odds quickly turned against the Celts. Outclassed on both sea and land, the High King in Dublin reached out to Al Andalus, hoping to open a second front against the French.

The nobles in the Majlis, eager to test their mettle against the French, were all too happy to join another war. The army is quickly resupplied and border fortresses are garrisoned, but action broke out on the sea first, with a large French fleet engaging an Andalusi-Breton navy along the coast of Brittany.

The battle ended in resounding success, with twelve French ships torched and sunk, including three large capital ships.

After being forced from the seas, the French shifted their focus to land warfare, invading Al Andalus with a 33,000-strong army. The French were renowned for their reliable and disciplined army, but the Andalusi were buoyed by news of their naval victory, so they rushed to confront the French at Balansiyyah anyways.

This battle would not go nearly as well, however. The wide, open terrain favoured neither side, and with the numbers roughly equal, the battle would come down to tactics and strategy.

And the Andalusi, who’ve been bullying significantly smaller and weaker states over the past two decades, simply couldn’t match the trained and tried French troops.

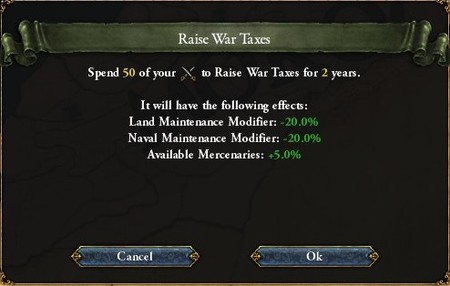

The Andalusi took heavy losses, leaving almost 13,000 dead and wounded behind them as they fled to safer territory, and news of this defeat hit Qadis hard. The Taifas hadn’t prepared for a long, expensive conflict, forcing them to impose a new war tax just to keep the treasury afloat.

But even this extra tax wasn’t enough to rebuild the army. Fortunately, the Almoravid Sultan was happy to lend a hand to his old allies, and sent several large caravans laden with steel and cloth and food to aid the war effort in the north.

More bad news followed, however. Around mid-1471, the Pope called for a crusade against Palermo, no doubt urged on by the neighbouring King of Italy.

The Italians didn’t hesitate to launch an invasion, with King Pericles personally leading an army as it stormed across the border, vowing to expel the last Muslim state from the peninsula.

(I didn’t dishonour the guarantee, because I never got called in. Italy actually declared war on Bari, which was guaranteed by Palermo.)

The Majlis had neither the men nor the money to intervene, however, not when the French were on the verge of pouring into Al Andalus. Instead, resources were devoted to bringing in fresh-faced recruits, equipping them with armour and arms, and training them to avoid a grisly death until they reached a battlefield, at the very least.

It took a few months to train the newly-recruited levies, but by October of 1472, the Andalusi were ready to attack the French once again…

And once again, it was all for naught. The battle was closer this time, but the Andalusi were thrown back all the same, handing another crushing victory to the French.

Balansiyyah was mere weeks away from surrendering, but fortunately for the Majlis, it didn’t come to that. In London, the Celts and the English finally agreed on a peace treaty, with England ceding a good chunk of its northern territories to the High King.

There wouldn’t be any celebrations in Qadis, however, not after the utter humiliation they’d been dealt on the battlefield.

And to make matters worse, Al Andalus was hit with another blow a few weeks later, with news of the Sultan’s death quickly spreading throughout the peninsula.

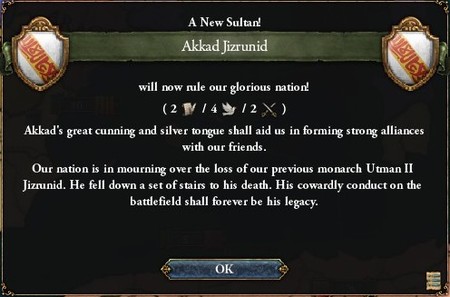

Utman II is succeeded by his younger brother, Akkad, someone who’s not a complete imbecile. Little is known about him, except that he’d previously served as a diplomat and emissary, though there are plenty of rumours regarding his brutish cruelty.

The Majlis, humbled after the disastrous war, rally around him nonetheless. The new sultan is crowned a few days later, and prepares to address the Majlis in an assembly soon afterwards.

World map: