Part 36: A New World

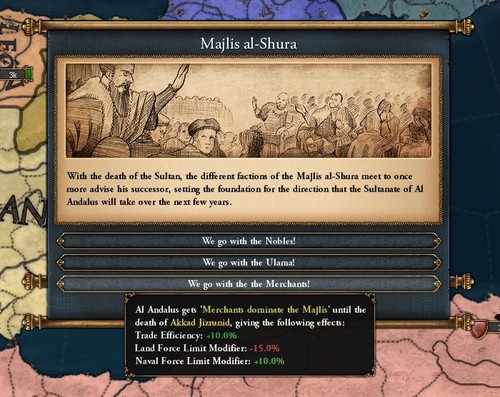

Chapter 4 – A New World – 1474 to 1490With the death of Sultan Utman II, the Majlis al-Shura met to determine the course Al Andalus was to taken over the next few decades. Utman’s reign had seen renewed expansion on the Iberian peninsula, but it had also drawn the ire of France, with Al Andalus soundly defeated after being dragged into the war by the Celts.

After the humiliating loss, the previously firm grip that the nobility had on the Majlis began to slip, with many of the more powerful lords switching their support to the League of Merchants.

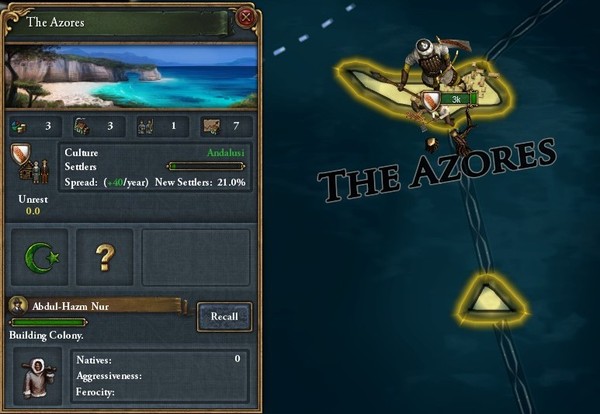

Rumours were abound regarding the discovery of large landmasses to the west, making their way to Qadis from the West African kingdoms. Before any exploratory missions could set out, however, the Majlis was determined to stake their claim to the recently-discovered island chain of Azores.

Coerced into joining through promises of land and money, the first ships set out for the Azores late in 1477, carrying the families who would found the first Muslim community in the west.They went with more than just hope, however, carrying food, cloth, basic tools, weapons and an array of other resources all provided by the League of Merchants, intent on setting up a well-developed and self-sufficient colony.

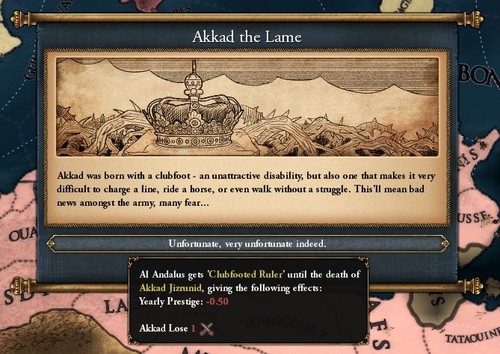

The Majlis, despite their undeniable power, was not the only voice that ruled in Al Andalus, however. Akkad had been offered the crown after the death of his half-brother, since Utman's owns sons were all mere babes, but very little was actually known about the new sultan, with his most distinguishable feature being his clubfoot.

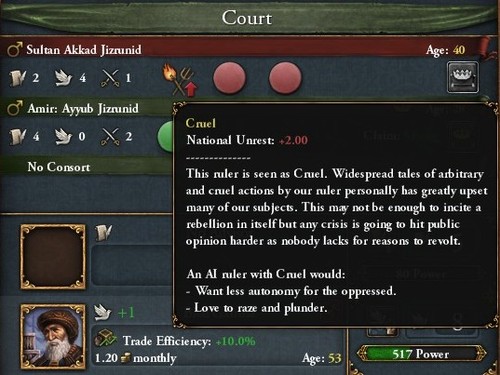

That wasn’t the only thing known about the new sultan, however. Akkad also had a reputation for being a particularly cruel, even sadistic man, openly threatening both his rivals and his subjects with gruesome torture and grisly executions.

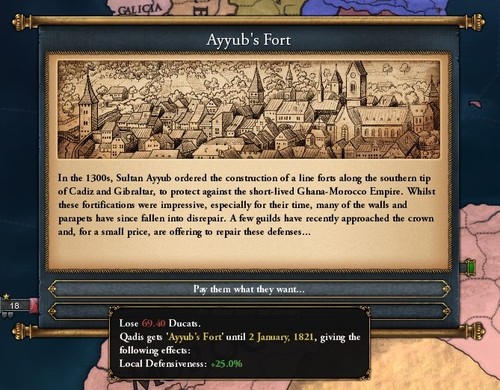

And though his clubfoot certainly dragged him back, Sultan Akkad was an avid supporter of all things martial, ordering the reparation of an old line of forts along the southern coast of Qadis and Algeziras.

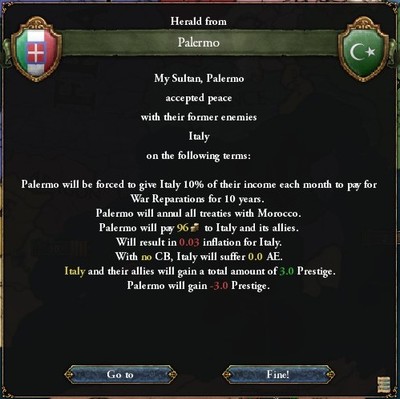

As power shifted hands and a new sultan ascended the throne, the gears that spun the world were still turning, and news arrived from the east early in 1478. After his army was annihilated in the early months of the war, Emir Abdul-Rahman Jizrunid of Palermo had agreed to make peace with King Pericles of Italy, with the two powers agreeing on relatively light terms.

Under the early rule of the League of Merchants, meanwhile, resources and money were invested into enlarging the navy, with two new capital ships joining the war fleet late in 1479.

The trade fleet was also expanded from 12 barques to 20, all sent to patrol the coasts of Iberia, protecting Andalusi interests from rival ships and pirates alike.

Before long, the Merchants had most of the trade in Iberia under their firm grip, raking in a majority of the money that flowed through Sevilla.

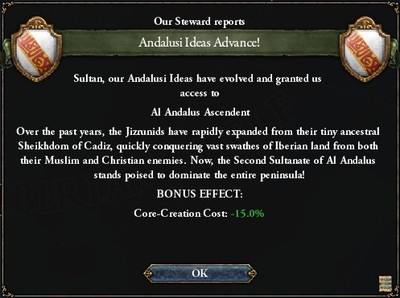

The Majlis had much more than just trade on their agenda, however. Under the tenure of the Taifas, Al Andalus had gradually fallen behind their rivals in technology, with Italy, Provence, France and even Castille making rapid military advancements.

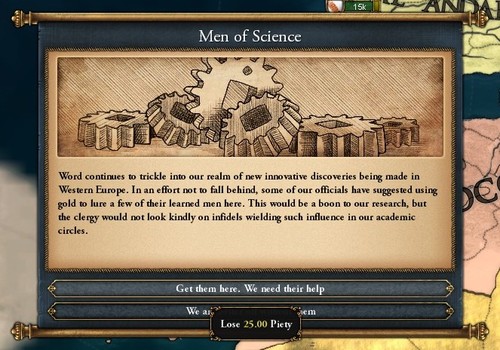

Desperate to catch up with their rivals, especially France, the Majlis invited a wide array of engineers and scientists to Qadis, bringing advanced knowledge of handheld weaponry and harquebuses with them.

The Merchants also invested into the development of various cities in Al Andalus, devoting significant resources to enlarging the mines of Al-Mansha, pumping it for all the gold they had.

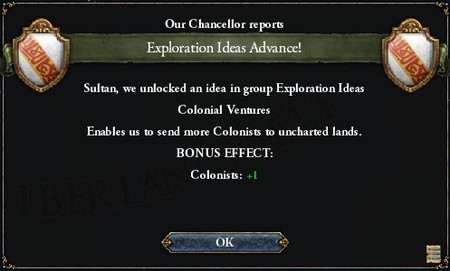

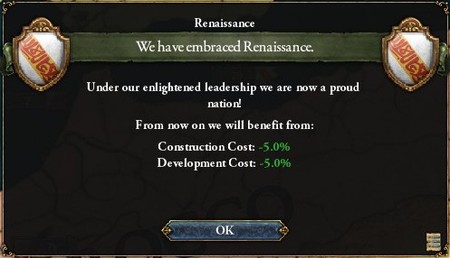

And before too long, it began to pay off. Ships were modified to carry out longer journeys, new administrative centres were constructed throughout Iberia, and the arquebus became standard equipment in the Mubazirun.

To the far north, war had broken out between England and the Celtic Empire yet again, and it was quickly becoming clear that the High King would not rest until the entirety of Britain was under his rule.

Further south, on the other hand, the bonds between Castille and France grew ever closer with the establishment of new trading contracts.

The France-Castille axis was quickly becoming a serious worry, especially since the Queen of Castille also held the throne of León, effectively uniting most of Christian Iberia under a single ruler.

The League of Merchants were determined to avoid war at all costs, however, and so the attention slipped away from Iberia yet again.

Instead, they began looking to shores further afield. In the Near East, both Egypt and Anatolia were under the firm grasp of Christians, landing a serious moral blow to the authority of Islam. It also meant that the spice trade that had once flowed from the Far East to Muslim Iberia was now being redirected to Christian Europe, this time a blow to the economies of North Africa and Al Andalus.

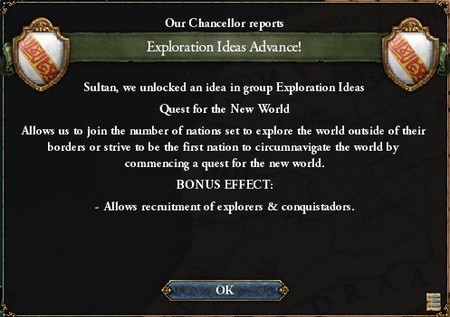

The Andalusi couldn’t exactly launch an invasion of Egypt, those days were long past, so a different approach was adopted. If the trade didn’t come to Al Andalus, then Al Andalus would go to wherever the trade came from…

By the summer of 1480, several large expeditions were equipped and ready to set out, sailing westward using sea charts purchased from the Jolof Sultanate. It would take several long months for them to hit land, but the expeditions would eventually make their return to Qadis, their ships laden with strange plants, peculiar animals and exotic peoples.

Any thoughts of actually colonising the newly-discovered continent, dubbed Ard al-Gharbia - the Great Lands of the West - by overenthusiastic explorers, was still out of the question. Instead, the focus remained on the Azores, which was slowly but surely becoming self-sufficient.

News of gold-laden cities and vast continents fueled the public imagination, but whilst all this was going on, the small circle of nobles still loyal to the New Taifas were focused on reclaiming their glory.

They began calling for renewed war with the Christians, claiming that it was the destiny of Al Andalus to one day span all of Iberia, unfettered from the Christians once and for all.

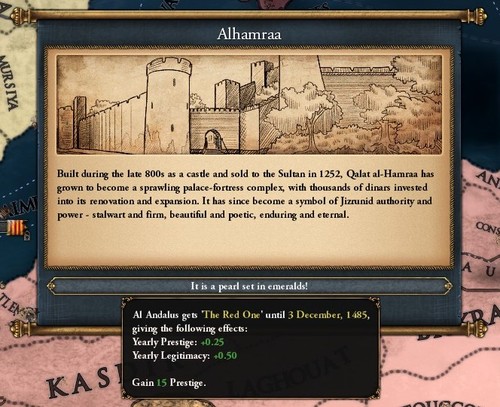

With the Taifas now a minority in the Majlis, however, these outbursts went ignored. Even Sultan Akkad, who had once been a major proponent of the nobility, began pursuing more artistic goals as he aged. After purchasing a large, ancient castle from the local sheikh of Granada, he spent his days repairing and renovating it, turning it from a ruin and into a jewel of a palace.

In the north, the Celtic-English war ended in another Irish victory. Celtic domination was quickly becoming inevitable, to the detriment of France, but it could only be good for Al Andalus.

Peace reigned in Al Andalus for a few short, blissful years, where technological innovation and artistic achievements were pursued above all else. As all good things do, unfortunately, it came to a sudden, abrupt end in the dying days of 1484...

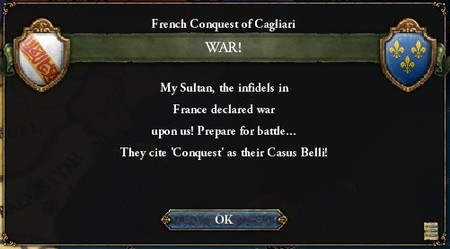

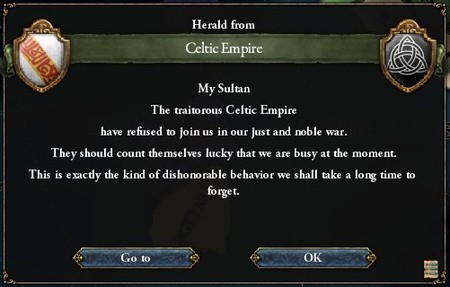

Another war with France. And to make matters worse, the Irish High King refused to join the conflict altogether, expelling Andalusi envoys from Dublin without an audience.

France did not face the same dilemma, with both the Merchant Republic of Provence and the Kingdom of Castille joining the war against Al Andalus.

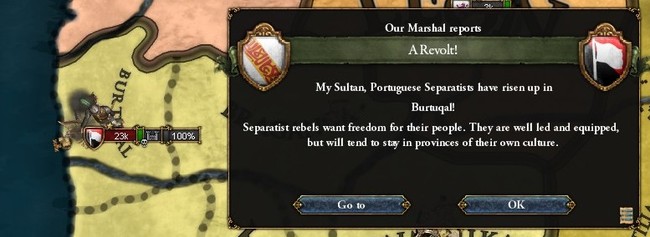

And it didn’t end there, because just days after this sudden turn of events, more bad news arrived with the outbreak of a massive revolt in Portugal.

So, for a quick tally, a war between Italy and Palermo suddenly broke out, followed by a declaration of war from France, a betrayal from the Celtic Empire, and the eruption of a massive rebellion in Portugal. Coincidence?

Whatever the case, Al Andalus had to act, and quickly. This is where Sultan Akkad came into play, eager to make his mark by taking overall command of the weakened Andalusi army, which was sent to crush the rebellion.

Even before the rebellion was quelled, however, the Christians had launched their invasion of eastern Andalusia, with a 20,000-strong Provencal-Castilian army laying siege to Balansiyyah.

The Sultan appointed the talented Mubashir Munya, who had risen to the rank of Amir in the elite Mubazirun Order, to personally lead the Andalusi levies. The commander engaged the Christians a few weeks later, scoring an important victory and sending them running before the day was out.

Just two battles in, and the manpower reserves were already taking a hit. Fortunately, the Almoravids of Morocco were still stalwart allies, and crossed into Iberia to aid their Muslim allies.

Together, the two armies attacked another Castilian force, this one much stronger and in defensive terrain. They put up a firm fight, but numbers won out in the end, and the Castilians were forced to fall back. They got away with relatively light losses, however, with the Muslims losing 7000 men to their 4000.

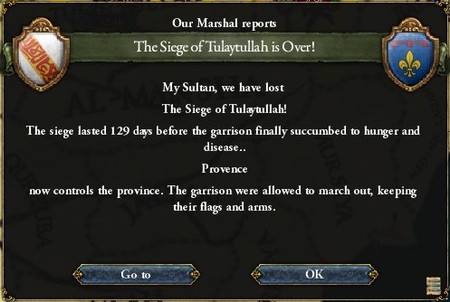

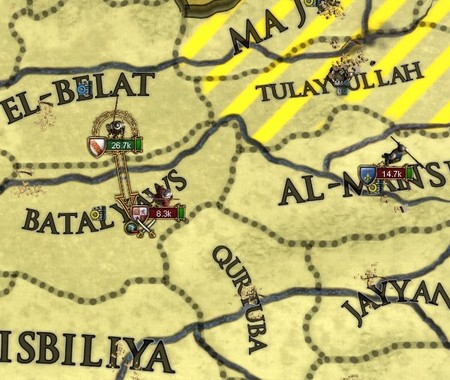

Nevertheless, there was no option but to march on. Sultan Akkad sent the Andalusi army to relieve a French siege of Tulaytullah, a strategically-decisive fortress, its fall would open the floodgates to all of Al Andalus.

At the same time, the Andalusi Navy finally managed to pin down an enemy fleet, engaging a smaller French flotilla in the straits of Gibraltar.

Both battles proved to be bloody. In Tulaytullah, French cannons meant that the Andalusi were on the backfoot from the very beginning, suffering devastating charges in the early hours of the battle. With imams shouting out Quranic verses and the Sultan urging his men on as the fighting raged, however, the French were gradually overwhelmed and defeated.

Just off the coast of Cádiz, meanwhile, a ferocious naval duel ended with the sinking of two French carracks. Their vanguard broken, the Andalusi navy managed to force them back to French coasts, harrying and burning their tail as they did so.

Any celebrations following these victories quickly died, however, when it became apparent that they were nothing more than a distraction. Whilst the Andalusi navy had been tied down in the Straits of Gibraltar, the French had managed to land a large army in North Africa, an army that was now rampaging across Moroccan-controlled Tunisia unopposed.

The Moroccans were forced to pull most of their troops back to North Africa, with the Andalusi navy clearing the way for them by defeating another Christian fleet, this time Provence’s.

Back on the front lines, meanwhile, yet another French army pushed into Al Andalus and besieged Tulaytullah. Amir Mubashir was forced to break off his own siege to engage the French, notching another impressive victory after a bitterly-fought contest below the walls of the city.

13,000 Frenchmen fell that day, but Sultan Akkad didn’t have much time to celebrate, because a second Christian army engaged him just one day after his victory.

Even the most gifted commanders would find it difficult to salvage a second victory in as many days, especially with wounded, tired men making up the vast majority of the army. Sultan Akkad managed to inflict a fair few casualties on the Christian army, but he was forced to call a retreat a few hours after the fighting broke out, with the battle ending in tactical victory but strategic defeat.

In North Africa, meanwhile, the French had managed to defeat the Moroccan army and were quickly pushing past Tunisia and into Algiers. The prospects of victory were becoming dimmer with every passing day.

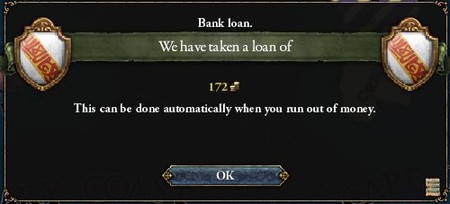

Akkad had no time to take note, however. The budget was in the red and the treasury was bare, so the League of Merchants were already calling for peace, but the Sultan refused. He was determined to somehow come out on top, so he decided to take out loans instead.

Using this flood of gold, Akkad reinforced his weary levies with fresh mercenaries, before sending them north to engage the Christians again. The Andalusi clashed with a small Castilian army at Majrit, but the battle was quickly reinforced by a large Provencal-French army, turning the tide against the Muslims and forcing them to retreat with heavy losses.

Again, however, Sultan Akkad rebuilt the army and pushed north. And again, the Christians rapidly reinforced any attempts to score a victory, and the losses quickly began to pile up against Al Andalus.

It was in the aftermath of this loss, with the broken Andalusi army fleeing to Qadis, that the walls of Tulaytullah were finally breached and the city, after being subjected to a brutal sacking, was captured.

This would have been a good time to make peace, to simply give the French what they wanted, but Sultan Akkad refused to hear any mention of surrender. So yet again, large loans were taken out from the Jewish communities to fund the war, and the crown slipped further into debt.

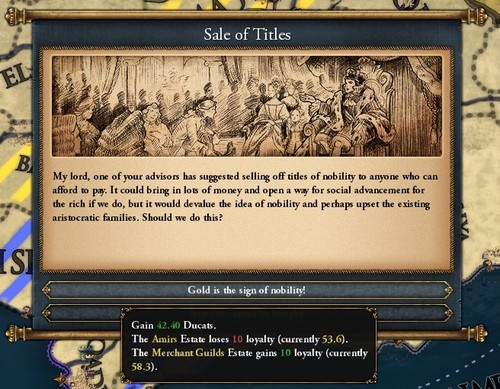

Desperate for every last coin, the Sultan even descended to the humiliating position of selling titles, mostly to the rich merchants eager to dress themselves up as nobles - the Ghizvanni, Farihids, Wassawi and countless others.

And again, all the money was directed into raising a new army, this one composed entirely of mercenaries.

In one final attempt to gain the upper hand, the sultan sent Amir Mubashir northward on another offensive, engaging a weaker Castilian army near the city of Batalyaws.

Christians were swarming across Al Andalus, unfortunately, and any hope of somehow dividing the different armies was pointless. Night came with another bitter loss, with a full half of the mercenary army wiped out.

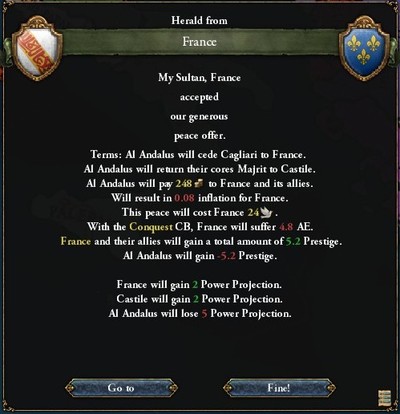

Sultan Akkad and the Majlis, at a loss for any alternatives, finally reached out for peace. After a few days of negotiation, the two parties agreed on a treaty, with the Andalusi ceding Cagliari to France and Madrid to Castille, along with large amounts of tribute, in return for peace.

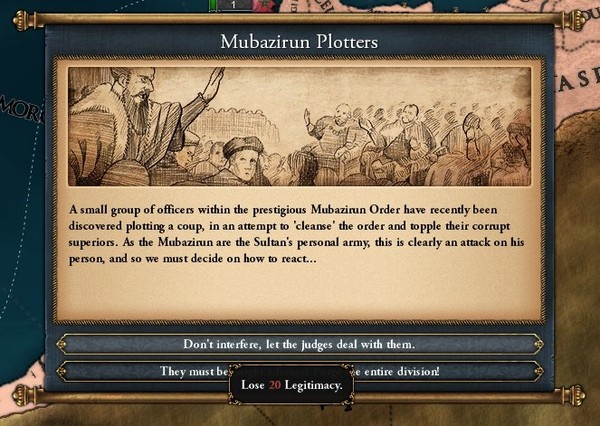

As the threat of rebellion became more likely, the guard around the sultan was increased, but even the Mubazirun Order – once the most disciplined force in all Europe – began entertaining thoughts of revolt.

As another decade ends and 1490 approaches, however, the landscape is radically different from what it had been just fifteen years prior. Sultan Akkad’s ascension has seen a power struggle erupt between the Majlis and the Sultanate, successful exploration abroad is shadowed by the devastatingly humiliating loss to the Christian powers, and Islam is on the retreat from Iberia to Italy to the Near East.

Whatever happens over the next few years, the one thing made clear is that the days of unchallenged Andalusi dominance are in the past, where they will remain.

World political map:

Religious map:

Great powers of 1490: