Part 37: The Grand Alliance

Chapter 5 – The Grand Alliance of the South – 1490 to 1506The last decade of the fifteenth century begins with tragedy. Ayyub, Sultan Akkad’s eldest son and heir, passed away after a bout of illness, sending the palace into mourning. Akkad copes with it by distracting himself with the pleasures of his harem, and before long, he fathers another son.

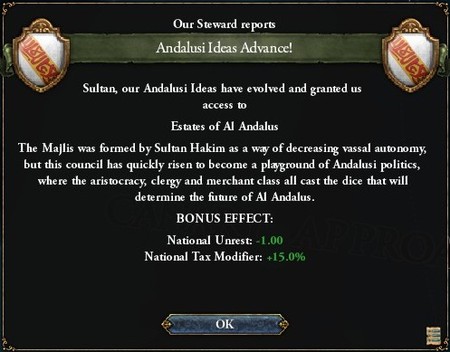

As the grief-stricken Sultan Akkad withdraws himself from public life, the reigns of governance pass to the Majlis. Blame for the humiliating loss to the French had fallen squarely on the shoulders of the Merchants, so they began a program of reform and modernisation, appointing a prominent nobleman by the name of Rasiq Bilalid to drill the army.

At the same time, the Majlis also initiated the construction of barracks in all the most populous cities of Andalusia, most notably Qadis and Tulaytullah.

And slowly but surely, Al Andalus began to recover from the war and recuperate its losses. Prospects began to look up as manpower steadily recovered, new levies were recruited and drilled, and Rasiq personally trained the next generation of Andalusi officers. By early 1495, the last of the ill-advised war loans were finally paid off, making the crown solvent once more.

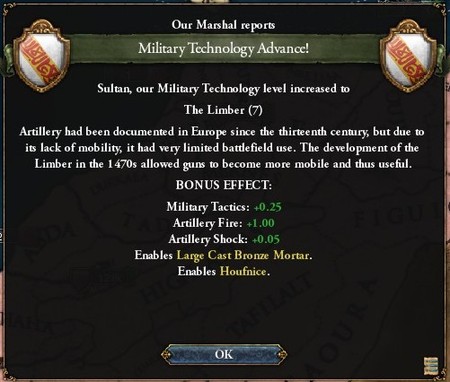

With the Sultanate no longer in debt, money could be invested into other avenues of interest, especially that of the military. Prominent members of the League of Merchants invited German contacts to do business in Qadis, and in return for hefty donations, these contacts brought technology and innovation with them.

More specifically, they brought mortars with them. These were the same weapons the French had used to barrage and blow apart the walls of Balansiyyah and Tulaytullah in the recent war, devastating and destructive. Five mortar regiments were quickly ordered, with foreign officers training the men who would operate them.

This was all well and good, but the fact of the matter was that France simply could not be matched on the battlefield, not whilst their alliance with Castille held fast. So at the behest of the Majlis, envoys were dispatched to increase relations with nearby kingdoms, seeking alliances and defensive pacts wherever possible.

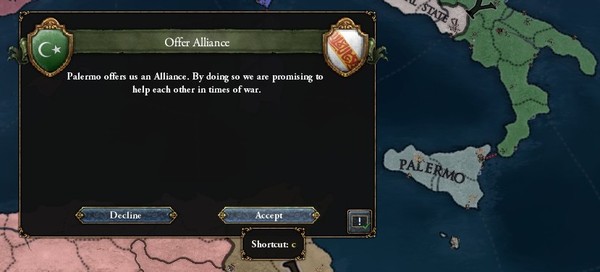

This bore fruit early in 1496, when the Emirate of Palermo reached out to Qadis for an alliance. Palermo was small and weak, its glory days far behind, but Al Andalus was in desperate need of allies, so the offer was accepted and an alliance forged.

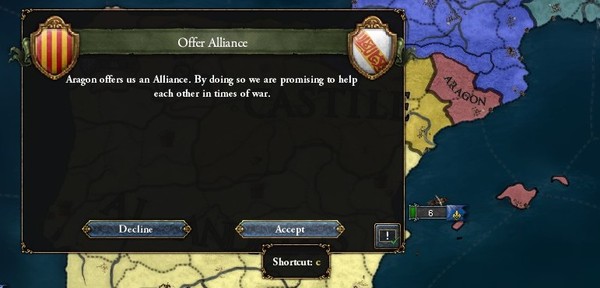

Shortly afterwards, however, a surprise arrived in the form of Aragonese diplomats. Stretching back to their founding father in Cyneric the Bastard, the Kings of Aragon had always been staunch enemies to Al Andalus - until now. Overshadowed and threatened by the French and the Castilians, they were determined to negotiate an alliance with Al Andalus, and they offered to marry a young princess to the Sultan's brother to cement their newfound pact.

Despite loud protests from the Taifas and Ulema, the Merchants recognised that a greater enemy now threatened both Al Andalus and Aragon, and decided that it would be useful to have an ally on the Iberian peninsula.

Meanwhile, in North Africa, the Sultanate of Morocco had been facing considerable internal problems. Precipitated by the French invasion, Tunisian nobles had rallied behind a local emir and rose up in a massive revolt, defeating the weakened Moroccan army in a string of battles.

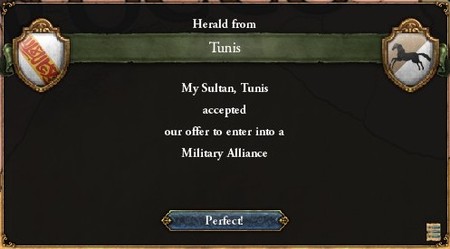

The newly-independent Emir of Tunis was very hostile to both Morocco and Egypt, understandably. The Majlis sent an embassy to open relations with the emirate, and despite protests from the Almoravid Sultan, an alliance was signed between the two powers shortly afterwards.

Thus, by early 1497, Al Andalus had managed to form pacts uniting Palermo, Tunis, Morocco and Aragon into a grand alliance - an alliance that would later be dubbed the "Alliance of the South". Most of these states were small and weak, however, and the danger of it being unraveled was all too real.

The greatest danger to Tunis, for example, was Crusader Egypt. The king in Alexandria had led several campaigns into the Levant, pushing beyond Jerusalem and conquering vast tracts of land from the Fatimid Caliphate. Its only real rivals were in Nicaea and Persia, both of whom were embroiled in wars of their own.

Back in Iberia, however, attention gradually began shifting back to the west. The nascent Andalusi colony in the Azores had blossomed over the past few years, with a stable population and heavy tolls exacted on shipping enabling it to become self-sufficient.

The Merchants didn’t stop there, however. The vast continents in the west were still beyond reach, but the Majlis was also eager to trade with the countries of West Africa, where countless tales of riches originated.

To that end, a small trading post was constructed along the edge of the El Djouf desert.

The locals proved to be much more of a nuisance than the natives of the Azores, however, with the tribesmen carrying out several deadly raids, massacring hundreds of colonists as they did so.

Nevertheless, the trading post quickly proved to be a commercial success, attracting merchants and traders from the Jolof Sultanate. Maps of sea routes and coastlines were purchased from these merchants, making it significantly easier and safer for Andalusi explorers to make their way to the New World.

Further north, meanwhile, a tense peace between France and the Celtic Empire erupted into chaos as thousands of Frenchmen flooded into Brittany.

Allies were quickly called in on both sides, with Castille and Provence joining the French, and Lorraine and Gwynned rushing to the defense of the Celts. France would quickly occupy the rest of Brittany, but the British Isles would be off-bounds, with its fleet sunk by the Celts within days of the war breaking out.

In Al Andalus, spectators observed the war with interest, but no intention of intervening. No, resources would be channeled into colonies and trade, war simply wasn’t good for business.

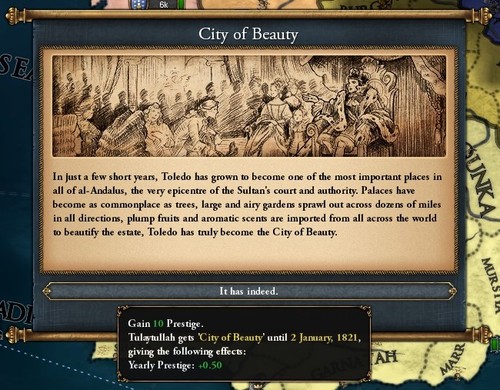

Whilst the Majlis solidified its hold on the government, Sultan Akkad focused on more artistic pursuits, becoming remarkably libertine as he became older.

He took a great interest in the arts, inviting painters from France, sculptors from Italy, philosophers from Germany, poets from Palermo and writers from Tunis to his courts.

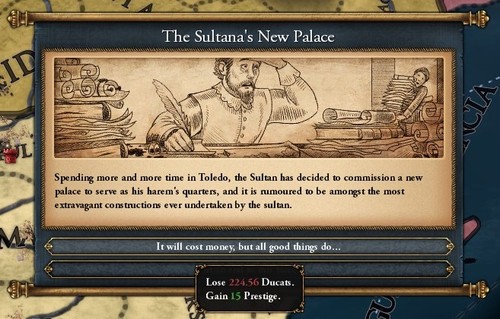

Not only did he invite all manner of peoples, however, but he also commissioned outlandish and unprecedented architectural feats, such as the construction of entire palace in Tulaytullah solely for the women of his harem.

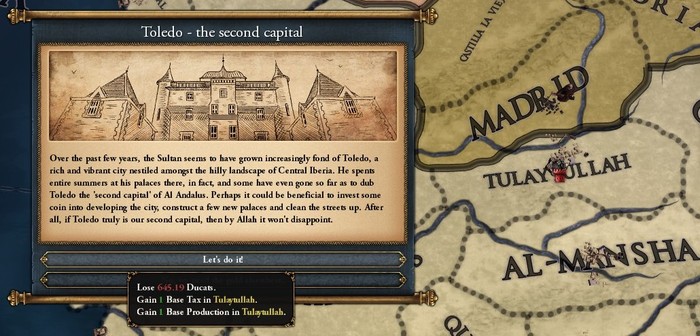

In fact, the Sultan gradually came to favour the pristine landscapes and vibrant culture of Tullaytullah over Qadis, which was crowded and chaotic by comparison. He became something of a patron to the city, ordering the construction of magnificent palaces and mosques, establishing airy gardens and public baths, and opening up new schools and universities.

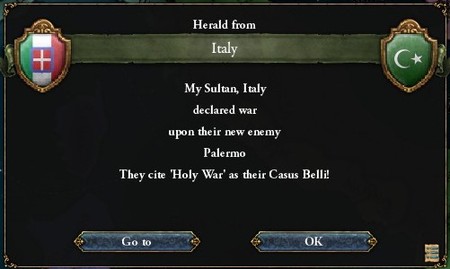

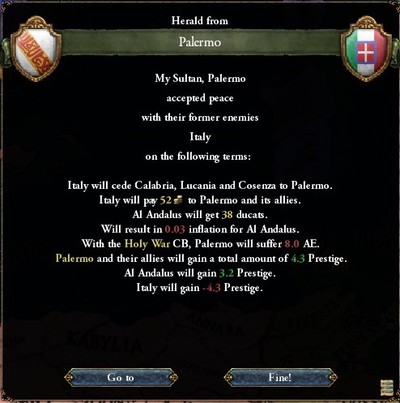

Whilst the Sultan busied himself with his city, the attention of the Majlis was fixed to the east, where war had broken out yet again between Italy and Palermo. And this time, Pericles - styling himself as the great restorer of the Western Roman Empire - boasted of his intention to finally conquer all of Palermo.

As was expected, Emir Abdul-Rahman quickly dispatched envoys to Qadis, begging for aid to at the very least repel the Italians.

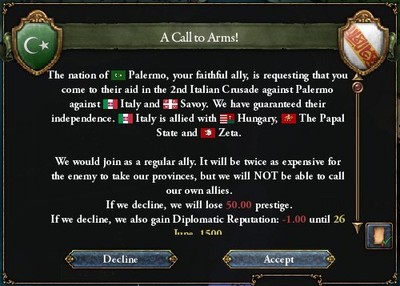

Ordinarily, the Merchants would have adamantly refused to involve themselves in war. The Alliance of the South was still very young, but Al Andalus was on the rise again, and it needed to prove itself on the world stage, to showcase its modernised military, to reassert its influence abroad.

After all, what’s the use of cannons if they’re never to be fired?

The call to arms were promptly accepted, and preparations for war were quickly underway. It took a couple months to ship over the expeditionary force, consisting of 24,000 trained and drilled levies, but a powerful fortress at Messina had kept the Italians at bay until then.

The Andalusi navy was quickly sent to patrol the coasts of Messina, to prevent reinforcements from pouring across the strait, whilst the Andalusi army marched across the width of the island to engage the Italians.

Ibn Sa’d led the Andalusi, and despite employing novel tactics and gaining the upper hand early on, the Italians managed to rally around their commander and launch several devastating counterattacks. The Andalusi retreated after three hours of heavy fighting, but despite losing the battle, they managed to inflict severe damage onto the Italian army, which lost 12,000 seasoned troops.

Towards the end of 1501, Ibn Sa’d felt confident enough to launch another attack, engaging the Italians in the second battle of Messina.

The battle opened with early victories for the Italians, but their firepower was outmatched by the Andalusi’s and their mortar divisions were quickly destroyed. The battle shifted in favour of the Muslims after that, with the enemy infantry routed after a couple hours of heavy fighting, before being thrown across the straits and back into Italy proper.

At the same time, the Andalusi navy had been pinned down by the smaller Papal fleet, though it easily gained the upper hand and forced the enemy to withdraw to Rome.

Back on the mainland, meanwhile, the Emir of Palermo launched an invasion into Italy, only to be brought short by a large Papal army. Ibn Sa’d rushed to reinforce the battle, scoring another impressive victory and sending the Pope’s forces running.

Another naval battle had broken out along the coasts of Messina shortly afterwards, this time between the Andalusi fleet and a large Italian navy. Once again, however, the Italians failed to overcome their numerical inferiority and were broken, with seven ships destroyed or lost to the enemy.

At the same time, news arrived in Qadis about the possible outbreak of a revolt in Portugal. That could not be allowed to happen whilst the army was engaged overseas, so a small but brutal police force was sent to deal with any dissidents, massacring hundreds of civilians in Porto and al-Adna.

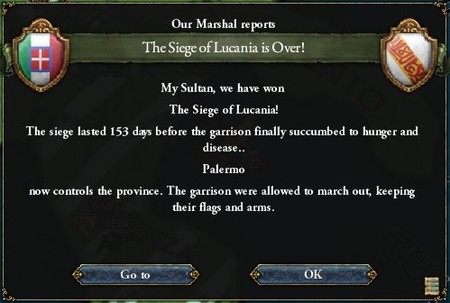

Back on the war front, meanwhile, the Andalusi army had pushed further into Italy and besieged Lucania, with the war fleet patrolling the Gulf of Taranto and blockading the city.

And with cannons blowing apart the walls of Lucania, the fortress finally succumbed a few weeks later.

The Andalusi navy, which was doing everything it could to keep the Papal and Italian navies separated, engaged the Papal fleet along the coasts of Rome. The battle was very short, but when it ended the Andalusi victory streak on the seas numbered one more.

As news of yet another defeat reached Rome, an enraged Pope Innocentius ordered his army to engage the smaller Andalusi force at Lucania. Nearby Muslim armies quickly poured into Lucania to reinforce the battle, and with Papal forces outnumbered and outclassed, it could only end one way.

A couple days later, however, the Italian army arrived and rushed to engage the Andalusi. Despite the numbers being roughly equal, Ibn Sa’d managed to utterly annihilate the Italian army through a sweeping barrage of attacks, with almost four times the number of Italians falling as Andalusi.

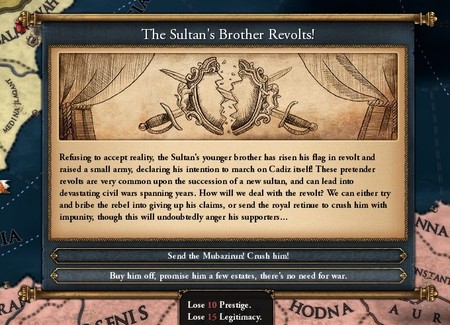

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the Majlis’ troubles were compounded with the rebellion of a Jizrunid noble named Ismail, a younger half-brother of Sultan Akkad, who demanded greater powers and authority. Another loan had to be taken out to pay him off, the only alternative to a civil war.

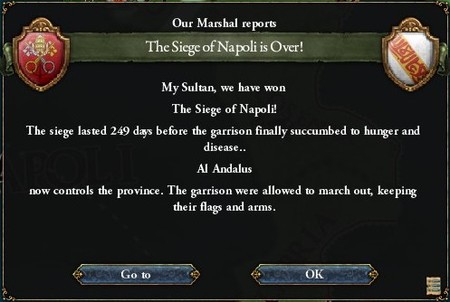

Meanwhile, back on the Italian peninsula, the Andalusi-Palermo armies continued the march northward. They besieged Papal Napoli, though the Pope’s forces launched another attack before the city could surrender, only for it to be decisively defeated once more.

The military situation relaxed as the winter of 1504 arrived, both sides content with capturing cities and sieging fortresses until the campaigning season returned.

Napoli finally surrendered to the Andalusi half a year later, disease-ridden and starving.

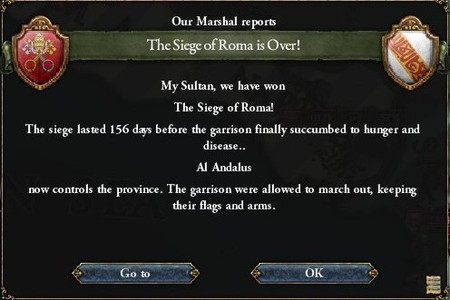

And finally, in the summer of 1505, Ibn Sa’d led the army to besiege the holy city of Rome itself.

Despite being surrounded on land and blockaded at sea, Rome managed to hold out for more than half a year in the hope of being relieved. No relief arrived, however, and when the walls were finally breached, the epicentre of Catholicism was subjected to another bloody sacking.

Lucania fell to Palermo not long later, and with that, the Christians were finally forced onto the negotiating table. Only tribute was demanded from Pope Innocent, but King Pericles was forced to cede a vast stretch of land in the south, from Calabria to Lucania.

And with that, the Andalusi fell back and withdrew their forces to Iberia, leaving an enlarged Emirate of Palermo in their wake.

Whilst the Andalusi had been embroiled in battles and sieges, the rest of the world had been warring as well. In the Near East, Nicaea had somehow lost a series of wars to the Armenian Sultanate, forced to surrender vast tracts of land. Crusader Egypt, on the other hand, had solidified its hold on the Levant by conquering the scattered Syrian emirates.

In the north, meanwhile, the French-Celtic War had devolved into a stalemate, with the Celts unable to retake Brittany and the French unable to cross into Britain. To make matters worse, a punitive war had broken out between the expansionistic Archbishopric of Liege and a number of German states, with Liege dragging France into the conflict.

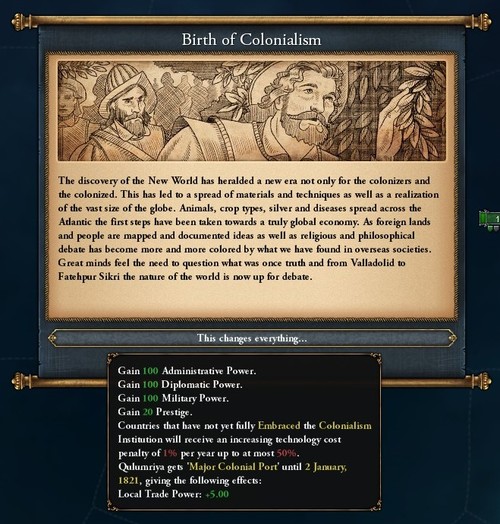

Whilst all this was going on, however, the Merchants had continued their obligations in the west so that by 1506, the numerous sea routes linking the New World and the old had been sailed through and mapped.

And even better, a chain of large islands had been discovered and charted over the past decade, islands said to be laden with sugar, gems, gold and other riches.

Before the Merchants could expand their interests to the Juzur al-Qarbiya, however, they were determined to solidify their hold on the islands linking the two worlds. So efforts to colonise the newly-discovered Cape Verde along the coast of Africa began, with several groups of settlers dispatched from Iberia over the course of the past year.

All of this had fueled stories throughout Europe and North Africa, where peasants, courtiers and nobles all gossiped about the vast continents to the west, eating up any rumours about its peoples and their strange customs, speculating about the extent its fabled riches, obsessed with the pamphlets and books published by its explorers and conquistadors.

Apart from Al Andalus, only the Celtic Empire had begun to take an interest in the new world, but only the Andalusi had made efforts to actually claim these vast lands, turning Qadis into the undisputed centre of colonialism.

All of this was made possible through the League of Merchants, who realise that the end of their mandate is nearing as Sultan Akkad approaches his seventieth birthday. Over the past half-century, however, the Majlis as a whole has come to wield considerable power, power that only an exceptional sultan would be able to face.

Speaking of Sultan Akkad, the old man spent his days strolling through his vast gardens, enjoying fine wines, advising his sons and playing with his grandchildren. He still resides in Tulaytullah, a city which has grown to become the cultural capital of Al Andalus over the course of his long reign.

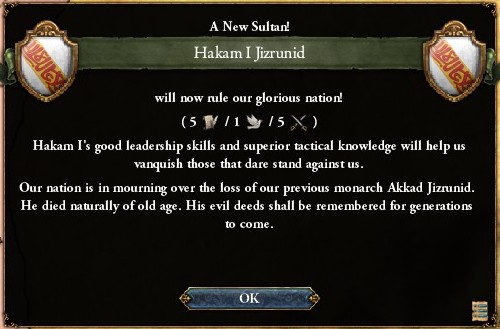

And it is in his city of beauty that Sultan Akkad dies, passing away in his sleep late in 1506. Akkad had hand-picked one of his sons as his heir, but chaos erupts in the hours following his death, and when the smoke finally clears it is one of his many half-brothers who is crowned instead...

As is tradition, Hakam prepares to address the Majlis shortly after his coronation, ready to wield the powers of Sultan.

World map: