Part 40: The Mighty King of the South

Chapter 8 – The Mighty King of the South – 1540 to 1555With the dawn of 1540 and the death of another sultan, the dominant hold that the League of Merchants once had on the Majlis finally began to wane. In the 70-odd years since they first gained a majority, they had managed to improve provincial administration and tax efficiency, modernise and enlarge the trade and war navies, draw up laws granting minorities rights, and most importantly, lead the world into the age of colonisation.

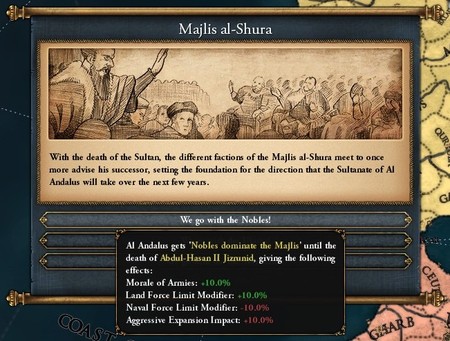

The ascension of a new sultan to the throne marked change in the Majlis, however. The New Taifas – mostly comprised of the proud aristocrats of the old noble families – used a colourful variety of bribes, threats and promises to attract a wide array of imams and petty lords to their side, displacing the Merchants as the largest faction in the assembly.

And this new sultan, Abdul-Hasan, fully backed the nobles in their endeavours. He was the youngest living son of Sultan Sayf, now being called "Father of Kings" by scholars and historians, since he was the fourth to be crowned Sultan of Al Andalus. He had been a mere babe when his eldest brother Utman ruled, a disobedient boy when his half-brother Akkad reigned, and a wilful commander when twin brother Hakam held power, but now it was him who wore the crown and held the sceptre. Now it was him who ruled.

He was just as ambitious and determined as his brother-kings had been, however, quickly marching to Qadis at the head of an army, forcing his many cousins and nephews to abandon their claims and submit to his rule.

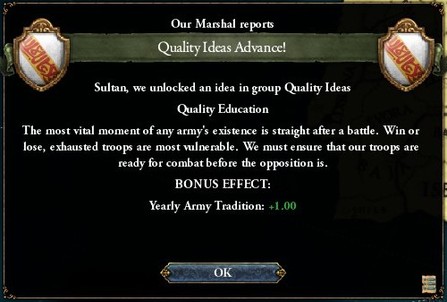

Abdul-Hasan had spent years on the march, either campaigning against the Christian principalities or crushing rebellions, he was a born and bred military man. Unlike his siblings, however, Abdul-Hasan was not interested in rushing into conflicts or leading from the front lines. He was a strategist above all else, content to wait for the perfect opportunity before striking.

Even before being coronated, however, the first stumbling block of Abdul-Hasan reign’s hit him mere days after the death of Sultan Hakam. A party of diplomats arrived from the Almoravid capital of Marrakesh, offering a renewed alliance between Morocco and Andalusia.

Abdul-Hasan had hoped to accept the offer, but upon presenting it to the Majlis, the antagonistic Taifas refused to entertain it, claiming that the Almoravids were rivals to them both in the old world and the new.

In fact, they went one step further than simply declining it. Mirroring what the Moroccans had done a few years prior, the nobles sent the envoys back to Marrakesh free of their heads.

Sultan Abdul-Hasan himself wasn’t interested in petty insults and mud-slinging contests. Instead, he established a new military base in León, from where he began efforts to bring Andalusi guns on par with those of the French.

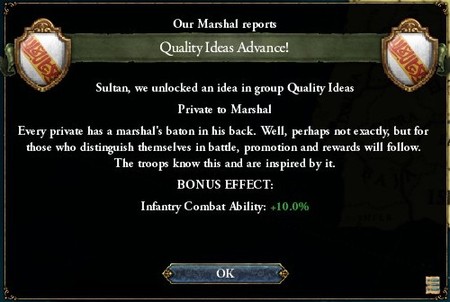

And before long, his efforts yielded results. The New Mubazirun was constantly being expanded, with its soldiers raised to march and fight as a single unit from boyhood, armed with harquebuses and muskets every waking minute, ready to carry out raids or offensives at a moment's notice.

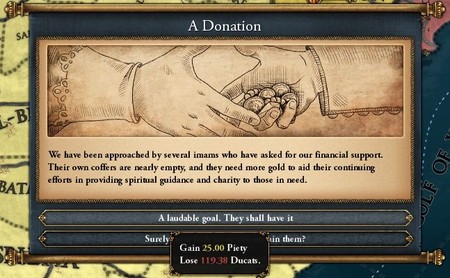

Abdul-Hasan, however, also began to tentatively support the Ulema, the scholarly and religious body of Al Andalus. His brother’s conquests had given Andalusia a large and unruly Christian minority, and since Abdul-Hasan had always been the one quashing their revolts, he knew just how dangerous a coordinated rebellion could be.

So he authorised the use of more aggressive tactics to help… coerce the Christian populace into conversion. Abdul-Hasan gifted the clergy with large donations from his personal treasury to help fund them, and before long, missionaries and zealots had infiltrated Portuguese castles, Castilian cities and Leónese courts.

The religious problems in Andalusia were nothing compared to the turmoil brewing across Europe, however. The Protestant Reformation had sunk its roots deep, refusing to budge an inch over its demands, to the ire of both the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor.

In fact, the clash between Catholic and Protestant had turned violent in countless cities all across Germany, with rulers cracking down harshly on any dissidents or heretics within their territories.

Nowhere was the Protestant-Catholic feud more bloody than in Britain, however, where the French had managed to decimate the Celtic army and conquer their way up to Scotland.

After three years of ruinous war, High King Máel finally agreed to meet in Normandy for peace negotiations, and the terms forced upon him were harsh. In addition to shiploads of war reparations, the Celtic Empire was forced to cede significant stretches of southern Britain to both France and England.

Whilst the Celts began floundering in the old world, however, their overseas ventures were going much better. With the backing of the Pope, King Máel declared that all of the New World was part of his dominion, with the first of his many colonies established at Albionoria.

To the east, meanwhile, yet another war had erupted between Italy and the Provence-Bavaria alliance.

Even further east, Sultan Berdar had conquered the last castles under the control of the Sultanate of Rûm, allowing him to solidify his own claim on the historic title.

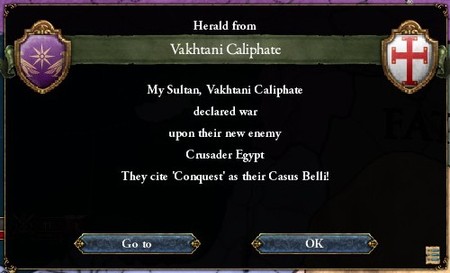

Berdar was already being called ‘the Conqueror’ by his adoring subjects, and true to his epithet, the Armenian sultan continued on his warpath by launching another invasion of Crusader Egypt. This time, he vowed, the Holy City of Prophet Isa would be freed from Christian occupation, once and for all.

Back in Andalusia, Sultan Abdul-Hasan was planning an invasion of his own. The New Taifas were already calling for war with Castille and Almoravid Morocco, but the Sultan wanted to test the mettle of his troops first, and decided on the small and weak Princedom of Galicia instead.

Abdul-Hasan appointed one his most trusted commanders to lead the war effort, Ali Ahmed. Ali had begun his career as an unremarkable engineer, but his familiarity with artillery both on the battlefield and off it led to him rising through the ranks very quickly, with the commoner now commanding a 21,000-strong force on the outskirts of Galicia.

War was declared late in 1546, and Ali Ahmed personally led the New Mubazirun straight towards Galicia, engaging the princedom's token force below the walls of the city.

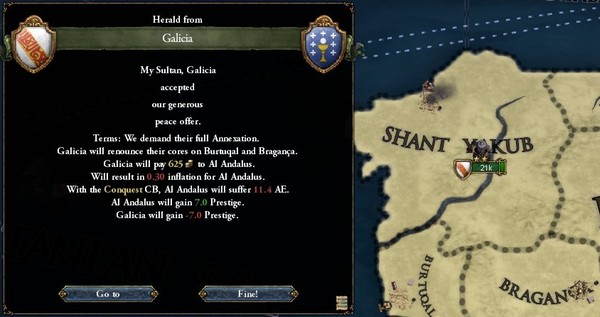

Unsurprisingly, the Galicians didn’t put up much of a fight. With the battle quickly decided in Andalusia’s favour, Prince Alfonso surrendered without much more resistance. In return for his cooperation, Sultan Abdul-Hasan let Alfonso continue ruling the city in his name, incorporated into the greater Iberian sultanate.

Despite being short and one-sided, the war did help Abdul-Hasan develop a more rigid command structure, dividing up the army into smaller units, each with its own commander. He also had his infantry corps re-equipped with better muskets, turning the guns from specialist arms to more regular equipment, and fully replacing the obsolete arquebus with time.

Galicia was not small or poor, but a single city was nowhere near enough to sate the Taifas' appetite for war, and before long their attention was drawn north. Castille still ruled over some of the richest cities in Iberia, including Burgos, and it had easily been defeated in their last war. Surely another war would end just as quickly, with the Castilians swept aside and forced to fully submit...

Unfortunately, it would not be so easy this time. Sometime over the past year, King Gundemaro had apparently negotiated an alliance with France, re-forming the old bloc staunchly opposed to Andalusi expansion.

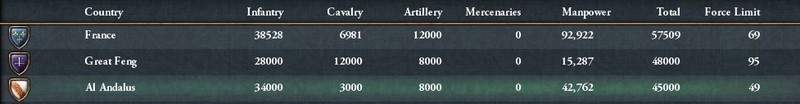

And that bloc was powerful, very powerful indeed. France alone could raise 20,000 more troops than Al Andalus, with another 100,000 manpower levies held in reserve. They were undoubtedly the most powerful kingdom in Europe, and they remained fierce rivals to the Jizrunids of Qadis.

Abdul-Hasan would have much preferred to wait for France to get bogged down in another war, it would surely be more prudent to attack whilst most of their army was trapped in Britain, or perhaps when they were distracted with another war in the Low Countries.

But in this matter, the sultan didn’t have much sway, not when the Majlis had already made clear their demands to see Castille humbled.

So as the summer of 1548 approached, Sultan Abdul-Hasan finally called another assembly in Qadis, this time to issue a declaration of war.

The New Mubazirun stood ready, and poured across the Andalusi-Castilian border even before the envoys had even left Qadis. The small and under-equipped Castilian army was defeated within days of the fighting breaking out, forced to retreat into the northern hinterlands and leave their capital undefended.

Before a proper siege could be set up, however, the first French wave arrived. A 30,000-strong force engaged the Mubazirun army at Burgos, but the battle was quickly reinforced by nearby Andalusi and Aragonese armies, pouring onto the field and hitting the French at their flanks.

Vastly outnumbered in both infantry and cannons, the French attack quickly proved to be a foolish one, and they were thrown back with relative ease.

With that, the rest of Castille was free for the taking, and the Andalusi quickly surged across it unopposed. Both Burgos and Vizcaya fell in quick succession, with their small garrisons holding out for mere weeks before raising the white flag.

Sultan Abdul-Hasan, moving his base of operations into Castilian territory, then instructed Amir Ali to besiege a French border fortress whilst he himself captured the towns in Navarra, a strategically-important mountain pass.

Labourd, surrounded by Andalusi men and siege weapons on land, and blockaded by six capital ships on sea, fell after just three months, bereft of supplies and ridden with disease.

Before he could push further into France, however, the Sultan was forced to re-direct his forces to the east, where a Castilian army had besieged Barcelona and a French army Valencia. After a brisk two week march, 48,000 Andalusi launched the offensive eastward and engaged the Castilians below the walls of Barcelona, quickly surrounding the smaller army.

Once news of the battle reached them, the French rushed northward and reinforced their Castilian allies, but their front line had already been broken and their flanks were on the verge of collapsing. The battle’s end brought 15,000 dead French with it, twice as many casualties as the Andalusi had suffered.

Mere days later, however, another French army descended from the north and attacked allied positions at Roussillon, which was being sieged down by Emir Abdul-Rahman of Palermo, recently arrived after a long trek through Italy and Provence.

The French were apparently led by their king, Adhémar de la Tour. A fairly decent commander, King Adhémar was unable to destroy the small army before Andalusi reinforcements arrived, turning the tide against the French and forcing them to fall back.

At the same time, a naval battle had broken out in the French-British Channel, where the French had pinned down the Andalusi navy after roaming too far north. Many expected an easy victory, but the French proved to be fierce fighters on the sea, blowing three capital ships to smithereens before the Andalusi had the sense to retreat.

And with that, the Andalusi navy suffered its very first defeat since its founding.

Back on the land front, meanwhile, Sultan Abdul-Hasan decided to take the initiative and launch a full-blown invasion of southern France. The French king had wandered too far south yet again, so the Sultan sent Ali Ahmed to force another retreat.

Under the leadership of Amir Ali, the Mubazirun pinned down King Adhémar in the grasslands of Narbonne, with both Arab and Aragonese reinforcements pouring onto the battle field as the fighting raged.

Adhémar had yet again overplayed his hand, Ali was able to demolish his force and send him fleeing long before another French army could arrive, handing another decisive victory to the Sultan.

Back in Castille, the last loyalist stronghold finally fell to the Muslims, with the starved mountain-fortress of Pirineos succumbing after a year-long siege. The victors, after establishing a garrison in the fort, began the march around the Pyrenees to reinforce the Mubazirun.

In the north, Ali Ahmed managed to bait another French army into attacking his position at Cahors, where he inflicted another humiliating defeat on them from a commanding position.

With two French armies broken in quick succession, the fortress of Cahors – the very gates of southern France – was free for the taking. After two weeks of siege, cannonfire managed to force a small breach in its walls, allowing the Andalusi to pour into the fortress and sack it without mercy.

Whilst busy assaulting Cahors, a newly-raised French army had circled around Andalusi lines and very nearly re-captured the under-garrisoned castle at Labourd. Ali Ahmed managed to outmaneuver the force at the last moment, however, crushing it with the entire might of the Andalusia-Aragon-Palermo army below the walls of the fortress.

With good news comes bad, however, as word arrived that the Andalusi navy had been crushed in another naval battle along the coast of Asturias. Andalusi supremacy over the seas was utterly destroyed with the sinking of three carracks – the last of Andalusia’s capital ships.

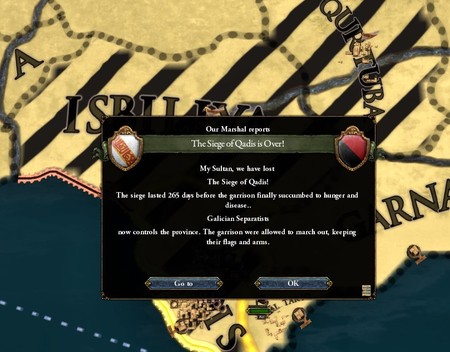

To make matters worse, a large rebellion broke out in Galicia a few days later. The rebels weren’t made up of peasants either, they were trained and tried soldiers, led by none other than Prince Alfonso of Galicia.

With a keen mind for war, Alfonso quickly struck south and began pillaging his way across the countryside, sacking and raping towns wherever they were. Sultan Abdul-Hasan briefly considered turning around to crush his rebellion, but with the French finally on the run, he couldn’t simply abandon all his gains.

So he resolved to get the war over with as quickly as possible, sending the Mubazirun to assault the fortress at Poitou. The fortress held fast, however, its sturdy walls throwing back wave after wave of Andalusi. Poitou only fell a year later, with Amir Ali forced to starve the city out.

With the fall of Poitou, however, the rest of southern France quickly came under Andalusi occupation. The army continued the march northward, diverting its route only to crush a Castilian army attempting to circumvent them.

There was only one more goal, and at long last, the enemy began quailing.

French envoys began flocking to Muslim camps en masse, begging for an audience with the "Mighty King of the South" to discuss peace terms, offering gold and land and all manner of concessions. Abdul-Hasan had them all turned away without an audience, and led the march to Paris himself, watching as his men surrounded the city and brought the cannons to position.

Hoping to relieve the siege, a French-Castilian force pushed northward again, drifting too close to an Andalusi army. Ali Ahmed pinned down the enemy force at Berry, where he barraged their flanks with cannonfire whilst he led the attack to destroy their centre, sending them fleeing towards Burgundy just hours later.

And a scant few weeks later, Paris fell to Sultan Abdul-Hasan. The capital of the Kingdom of France, one of the most populous cities in Europe, home to the richest kings in the world…

Abdul-Hasan did not hold his men back, and Paris was brutally sacked over the next few days. Its people slaughtered by the thousand, its palaces and mansions pillaged to ruins, its riches carted off southward in great caravans... Abdul-Hasan entered Paris a conqueror, and left it a city of ghosts.

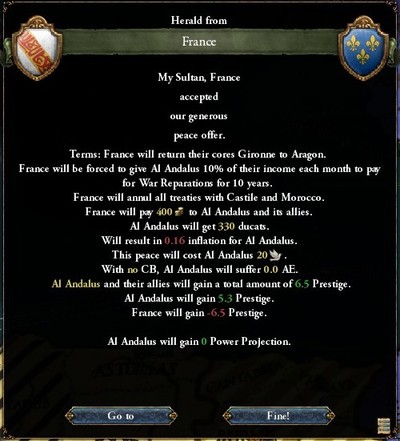

His will to resist utterly broken, King Adhémre finally surrendered unconditionally, agreeing to all of Abdul-Hasan’s demands. In addition to all the riches plundered from the capital, Adhémre also broke off all pacts with Castille and Morocco, as requested by the Majlis.

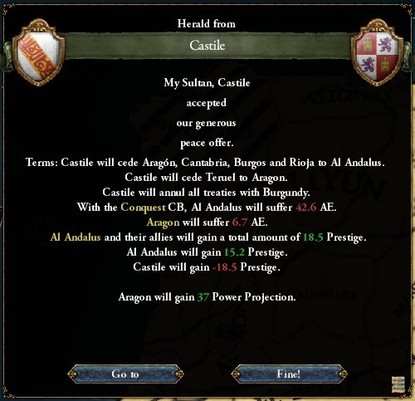

Castille, meanwhile, had been under firm Andalusi occupation for years now, and was forced to cede vast tracts of land in the official peace treaties, including its capital. Sultan Abdul-Hasan stopped to visit Burgos on his way south, where he delivered a speech in which he pronounced all of its citizens to be citizens of Al Andalus, guaranteeing their rights as part of the Castilian Dhimmi.

Sultan Abdul-Hasan thus returned to Al Andalus showered in glory. As he made sure everyone knew full well, with his chroniclers spewing out grand declarations and grossly-exaggerated poems by the dozen, but it was under his leadership that Andalusia had defeated France, avenging the humiliating loss of 1474.

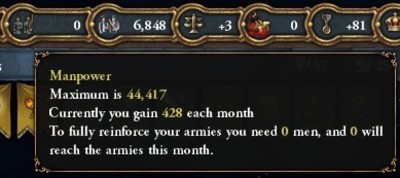

But it had come at a price, and a steep one at that. Thousands of dead littered the north, leaving the army at a fraction of its strength and its manpower reserves non-existent…

…and the navy had been hit even harder, with a grand total of 25 ships sunk by the French, including six carracks and five galleys…

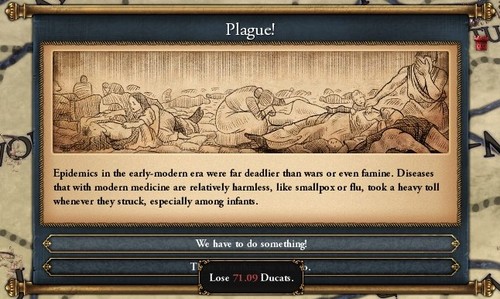

…with plague rampant all across Andalusia, sending thousands more to the grave and leaving the peninsula utterly devastated…

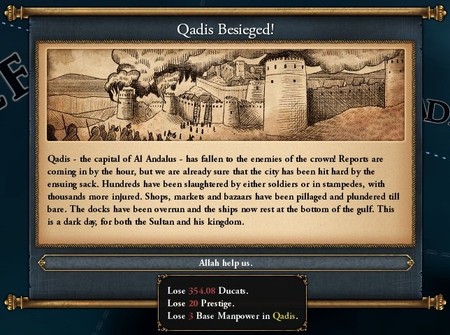

…but worst of all, Abdul-Hasan’s focus on the war had left Prince Alfonso and his rebels to riot across Al Andalus, ending his rampage by besieging Qadis. He managed to knock down a weak point in the capital’s walls before any relief force could arrive, his rebel troops streaming through the breach and into the city unopposed.

And in a sickening parallel to the Sack of Paris, Prince Alfonso unleashed his own army on Qadis. Exacting revenge for the slaughter of their own countrymen, the Galicians massacred thousands of Andalusi, killing men, women and children without distinction. Mosques were lit afire and left to burn, markets were plundered and destroyed, merchants ships were attacked and stripped of any valuables before they could escape. And along with a vast array of other governmental buildings, the Majlis Assembly was left in smouldering ruins by the time the rebels were done with it (though its members long-fled, obviously). Only the citadel had withstood the siege and escaped the ensuing sack, leaving the royal palaces untouched.

Sultan Abdul-Hasan arrived less than a week later, but it was already far too late, the damage had been done. That didn't stop him from ordering the Mubazirun to cut down the rebels wherever they were, even Alfonso was captured and tortured mercilessly, his eyes gouged out and flesh carved up until he died, with his head decorating a spike before day's end.

Once all the rebels had been killed and the city recaptured, Abdul-Hasan began plans to fortify the capital, so as to avoid another catastrophe. The Majlis, who had flocked back to the city behind the Sultan, were obviously in full agreement.

And with that, the year ended in bittersweet fashion. Abdul-Hasan and the New Taifas had been successful in their conquests, but half of Andalusia was still devastated by plague and pillagers, banditry was at an all time high, rebels were on the verge of rising up, and the capital would bear the scars of its sack for a very long time.

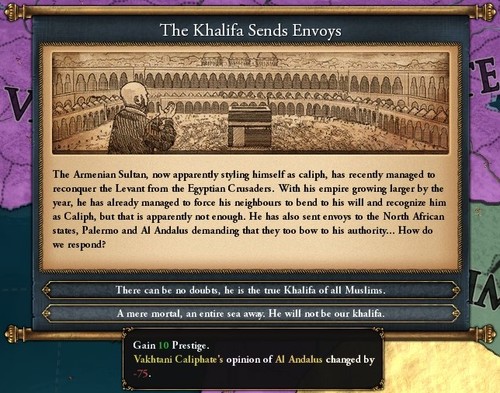

Shortly afterwards, news of another Armenian victory arrived from the east, with Sultan Berdar conquering Jerusalem from the Crusaders. For the first time in centuries, the holy city was in Muslim hands once more, lending even more legitimacy to Berdar’s Caliphate.

And Berdar certainly knew it. Any regional opposition to his claims melted with his conquest, with even Persia submitting after a short humiliation war ended in Berdar’s favour.

But he didn’t stop there. A large host of envoys arrived in Qadis a few weeks into 1555, bearing the rich purple colours of the caliphate. Speaking for their khalifa, they demanded that Sultan Abdul-Hasan recognise Berdar’s succession to the Caliphs of old, and send annual tribute in acknowledgment.

Abdul-Hasan was not a man known for bowing to others, however, and the envoys were sent back headless.

Sultan Berdar, much like Abdul-Hasan, was not a man to take insults lightly. He declared Al Andalus to be his eternal rivals, vowing to one day see his caliphate stretch from Yerevan to Qadis.

A reckoning between the two powers would certainly come, that much couldn’t be denied.

As the two largest Muslim powers began rocking back and forth, the same was happening within Christendom, where the Protestant Reformation had already caused rivalries to spiral out of control. Hoping to stem the rapid and unprecedented spread of Protestantism, delegates from Bavaria, Italy and the Papal States all met at Praha to discuss how to best combat and reverse its gains.

They eventually agreed on what was called the ‘Catholic Revival’, or the Counter-Reformation, with the Pope recognising and drawing up solutions to tackle problems within the faith, such as institutional corruption and the scandal surrounding indulgences, whilst also reaffirming the basic structure of the Church.

A host of Catholic nations embraced the Counter-Reformation over the next few weeks, hoping to gain the Emperor’s favour and bring about a halt to Protestantism.

It was far too late to reverse the reformation, however. The Catholic Revival gained no traction in Protestant states, which now included a few Baltic kingdoms, the majority of North German principalities and the Kingdom of France.

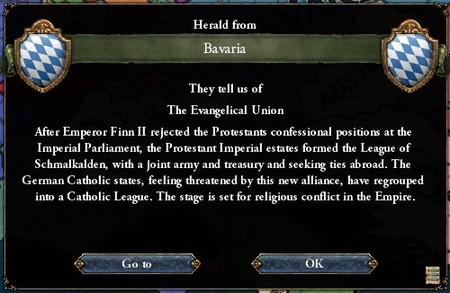

And all saw the Counter-Reformation as a threat to their interests. Meeting in Franconia, a host of German Imperial states agreed to form a coalition to defend the rights and lands of the Protestants of the Empire, dubbed the Evangelical Union.

The Emperor declared the union illegal, sparking a sudden declaration of guarantees from a number of kingdoms both within the Empire and without. The French King Adméhar announced his backing of the Protestant Union just days after its formation, with both the Celtic Empire and Provence lending their weight behind Bavaria in retaliation…

Within the space of a short few years, the reformation had monstrously grown far beyond any one man’s control, and Europe was undoubtedly set on the road to war.

The only question anyone in Qadis cares about, however, is what role Al Andalus is to play in the coming war.

World map: