Part 51: The Heretic Sultan

sorry for the long chapter, future updates should be shorter.Chapter 19 – The Heretic Sultan – 1680 to 1700

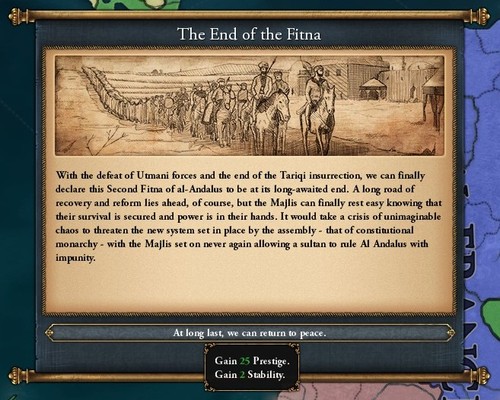

As a long century of discord began to wind down and approach its end, the decade-long Fitna of al-Andalus finally came to a close.

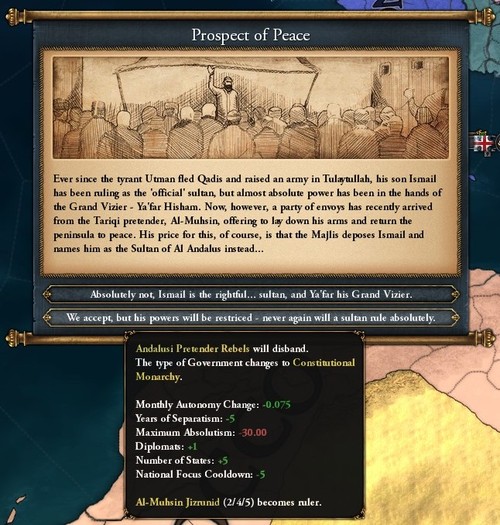

These ten years were the worst Iberia had suffered in centuries. It had seen fortresses torn down and towns pillaged, with cities captured and sacked. It had seen high nobles shot down from the saddle and power-hungry merchants blown apart in their palaces, with thousands of peasants massacred without a second thought. Only in the dying days of 1679 did the first prospects of peace finally come about, as the Tariqi pretender al-Muhsin reached out to the Majlis to try and negotiate an end to the conflict, a negotiation that would see him named the new Sultan of Al Andalus.

And with half the peninsula ravaged by war, the Majlis had little choice but to accept, though only on the condition that their authority be henceforth protected and enshrined in law. Al-Muhsin would still wield powers of his own, but never again would a Sultan plunge Iberia into such devastating depths.

Of course, many refused to recognise al-Muhsin’s ascension to the throne at all, fleeing the capital to join the loyalists and ulema that still held faith with the long-fled Utman. Al-Muhsin put a quick end to the last of these revolts, with the Majlis sweeping in to execute any prisoners once the battle was over.

And with that, the Fitna of al-Andalus finally came to an end. The Majlis emerged from the civil war triumphant, but the cost had been very high, with the death toll numbering in the tens of thousands, at the very least.

Few could predict what would happen to Al Andalus over the next few years, but only two paths stood open: either the sultanate would finally unravel and fragment, or it would slowly piece itself back together and stand firm.

The end of the Fitna did not halt the many crises associated with it, however. Not only was half of Iberia still burning as bandits and marauders scoured the countryside, but the economy itself was in tatters, with the Majlis heavily indebted to a wide array of foreign banks and moneylenders.

The reconstruction and recovery had to start somewhere, however, so the new Sultan al-Muhsin began his reign by naming a handful of Andalusi cities to the Majlis al-Shura, with the assembly appointing loyal courtiers to replace the rebellious sheikhs who’d once ruled them - these courtiers would eventually found their own dynasties, however, including the Farihids, Rawasim and Houdi.

The Majlis also awarded representation to its Leónese and Aragonese domains, hoping to mend broken bridges. A notable exception in the assembly, however, was the Castilians, the largest of Andalusia’s cultural minorities.

They were exempted from the parliament as punishment for joining with Utman the Tyrant, with Sultan al-Muhsin even tempted to strip them off their dhimmi status.

And with that, the new representatives of Iberia finally convened in the first assembly of the Constitutional Era, meeting in a newly-built hall in Qadis, not far from the Sultan’s royal palaces.

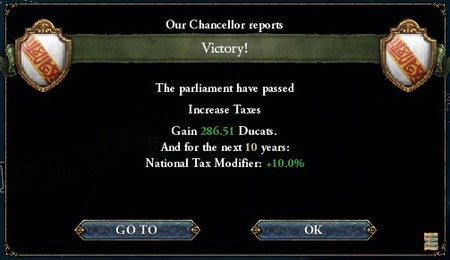

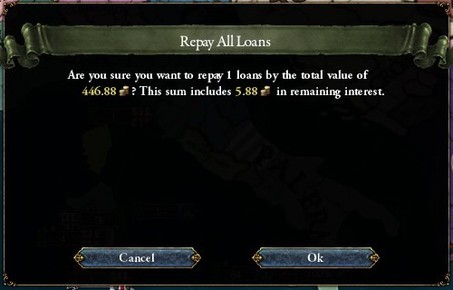

The many calamities and disasters looming over Iberia were daunting, but first and foremost, the financial crisis had to be dealt with. Despite already-diverging opinions in the assembly, the Majlis was quickly able to pass a series of bills authorising the Sultan to raise new taxes, determined to pay of its debts.

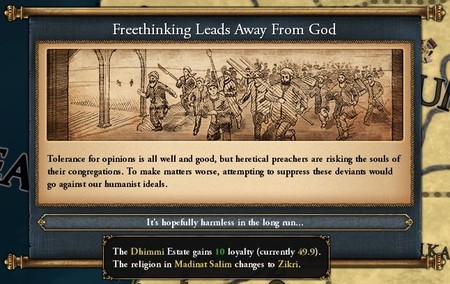

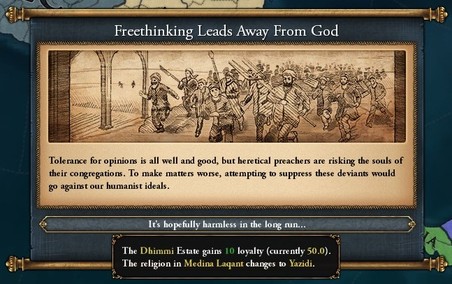

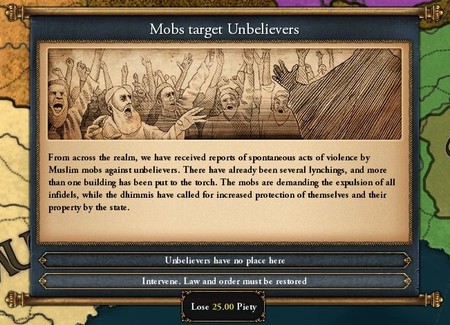

Money wasn’t the only problem the Majlis was facing, however, not by a long shot. In the years before the Fitna had broken out, the Majlis’ tolerance policies led to a stark rise of heresy throughout Iberia, with several cities quickly becoming strongholds of Zikri, Mahdavia and Yazidism.

This wasn’t much cause for worry, of course, so long as these minorities paid their taxes and didn’t pray too loudly. It is one thing to rule over a minority, however, and another thing altogether to be ruled by a minority.

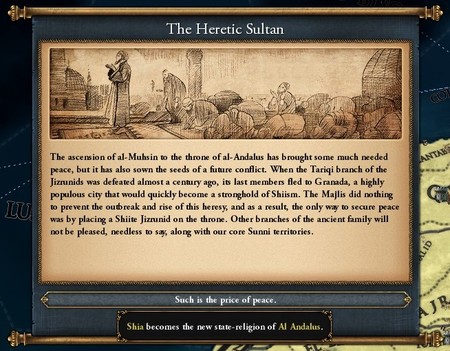

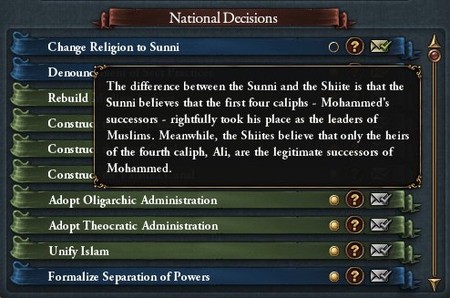

You see, al-Muhsin had been born and raised in Granada – a city famous for its Shia majority. The Majlis were fully aware of his faith when he proposed his peace, but they accepted the offer all the same, thus making him the first Shia Sultan to rule Al Andalus.

This was met with considerable opposition throughout Iberia’s Sunni populace, however. A notable sheikh in Catalonia even refused to pledge allegiance altogether, only relenting when he was granted considerable autonomy by the crown.

There was also a sudden rise in Shia-Sunni clashes amongst the peasantry, with violence breaking out more than once. The Majlis was forced to intervene countless times as riots threatened to break out, imprisoning dozens of zealots as they did so, even publicly executing a (somewhat insane) firebrand that claimed to be the "Dalai Ullama".

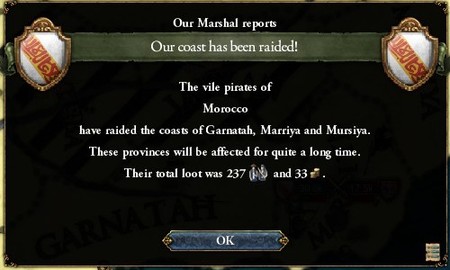

And internal opposition wasn’t the only threat to al-Muhsin’s rule, as several foreign powers denounced and condemned the Majlis for ever allowing a heretic to become sultan. The Almoravid Sultan of Morocco even began authorising raids on Iberian coasts, now rivalled to Al Andalus both politically and religiously.

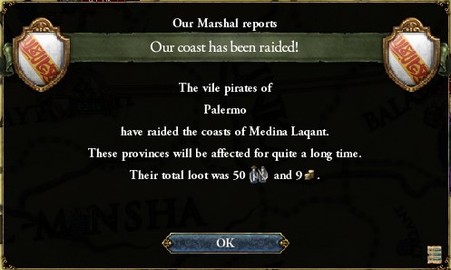

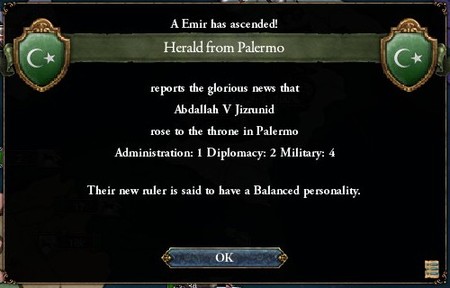

Still, hostility from Morocco was to be expected. What was less expected was the reaction of the Jizrunid Emir of Palermo, who immediately broke off his ties with Al Andalus upon hearing of Muhsin’s ascension.

This was followed by a series of raids on Corsica, with the Emir plundering the island in the name of Allah.

As opposition began to mount from all directions, many of the Majlis’ highest-ranking members pleaded with al-Muhsin to formally convert to Sunni Islam, but the sultan stood firm and refused to balk in his faith.

Instead, he founded a new organisation dedicated to spreading the ideals of Shiism amongst the Andalusi peasants. This new breed of clergy insisted that the doctrines of Sunni and Shia were more similar than they were not, merely two sides of the same coin.

And whenever these efforts failed, the imams struck hard and fast, quietly assaulting and imprisoning any would-be rioters.

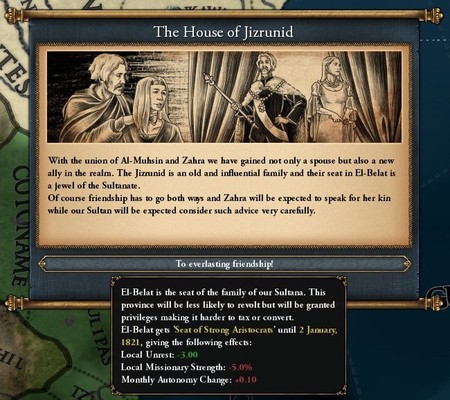

Eventually, however, al-Muhsin made some concessions. To try and ease tensions with his vassals, the Sultan agreed to marry one of his Sunni cousins, tying the rivaled Jizrunid branches together in matrimony.

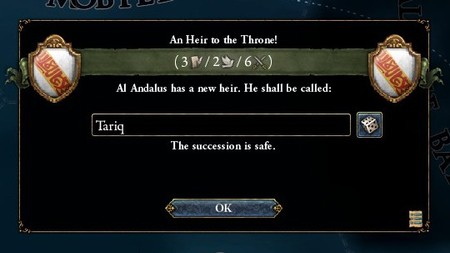

And despite his suspicions, al-Muhsin quickly took to his new bride, fathering a son less than a year after the marriage ceremony. The boy was named Tariq – in honour of Muhsin’s fallen ancestor.

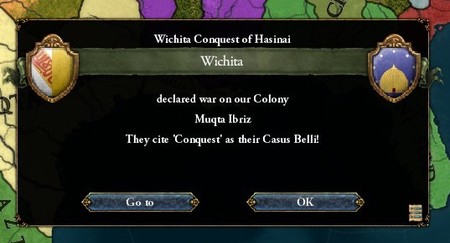

Whilst the Shia Sultan beginning to settle into his new position, another war broke out on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

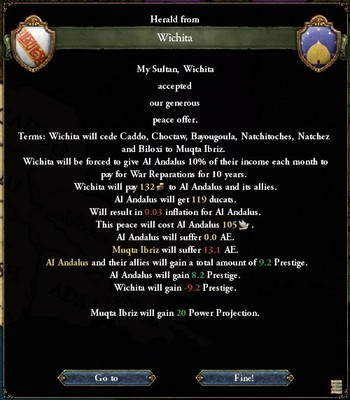

The native Wichita tribe had foolishly attacked and burned an Andalusi settlement in northern Gharbia, mistakenly assuming that the Sultanate was still embroiled in war.

And unfortunately for them, the army sent to repel the attack was led by none other than Salma Hisham – son of Ya’far Hisham, and a famed general in his own right. Salma quickly destroyed the native tribe in pitched battle, proceeding to capture its fields and hills over the next few weeks.

The natives capitulated within a couple months, forced to cede vast stretches of fertile land around the Mississippi. These territories were formally granted to the Muqta of Ibriz by the Majlis, who hoped a stronger colonial subject would repel any further invasions alone.

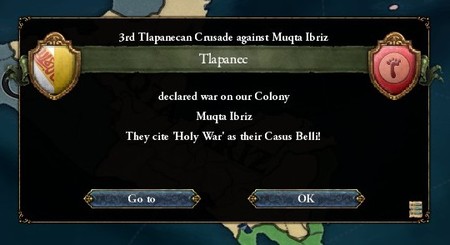

Ibriz wasn’t at peace for long, however, because the Tlapanec Emperor apparently decided that this was the perfect opportunity to reclaim the Yucatan Peninsula from the Andalusi colonisers.

The Tlapanec Empire was significantly larger and richer than the native tribes dotting north Gharbia, so Salma Hisham sent urgent requests for reinforcements from Iberia.

The Mubazirun had essentially been destroyed during the Fitna, however, leaving it a mere husk of its former self. The Majlis thus fielded an entirely new army together, consisting of almost 20,000 hired mercenaries, and shipped them across the Atlantic and to the new world.

Salma had already managed to push into Tlapanec territory by the time the reinforcements arrived, with native forces busy trying to capture Ibriz’s northern fortresses. Together, the two Andalusi armies pushed to the very gates of Tlapan City with almost no opposition, capturing vast stretches of land before a proper army finally stopped them.

Salma Hisham personally commanded Muslim forces in the ensuing battle, and though the numbers were roughly equal, Andalusi tactics and superior technology quickly prevailed over native muskets and obsolete cannons.

The battle ended with the Tlapanec suffering twice as many losses as the Andalusi, forced to retreat into the northern jungles and leaving their capital free for the taking.

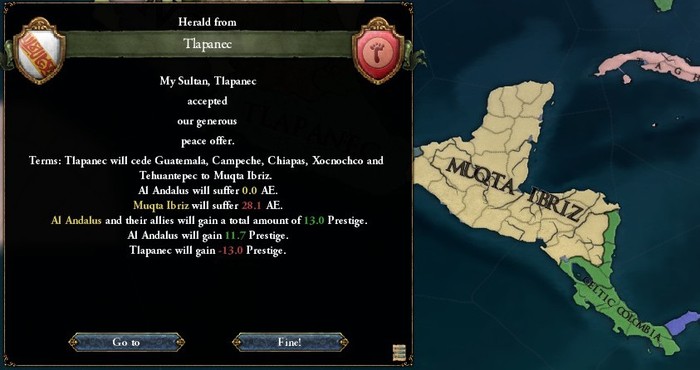

The rest of the campaign was a mop-up, with the Andalusi quickly capturing and plundering Tlapan City, setting it environs aflame and pillaging any nearby towns. Before long, the empire was on its knees, forced to surrender unconditionally.

Salma Hisham took personal charge in the peace negotiations that followed, demanding that the Tlapanec Empire cede the entirety of the Yucatan Peninsula, along with a few cities in Mexica proper.

Once the peace treaty was signed, large tracts of native gold quickly made their way into Andalusi coffers, and the Majlis named Salma as the new "Muqti of Ibriz" shortly afterwards, following in his father’s footsteps.

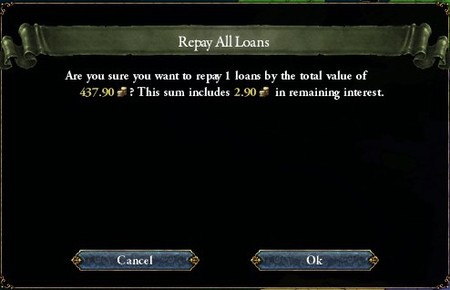

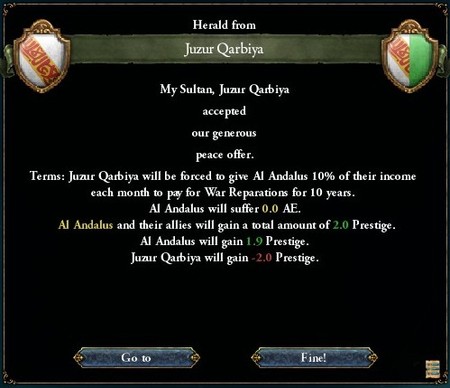

Of course, all the gold was quickly put to repaying the Majlis’ many loans, along with the war indemnities previously exacted on the native Wichita tribe.

With two wars won and almost half its debts paid off in quick succession, the economy finally began to stabilise once more, as the Sultanate of Al Andalus laboriously stood on its own two feet again.

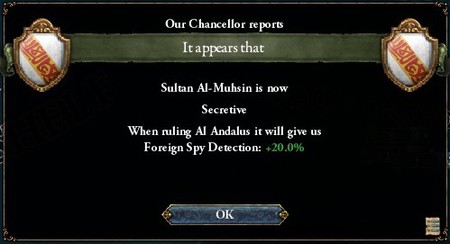

Sultan al-Muhsin, meanwhile, was busy meeting with foreign diplomats and dignitaries.

By the end of the Fitna, almost all of Andalusia’s allies had either abandoned or broke off ties with her, leaving Iberia at the mercy of its neighbours. The new Sultan quickly managed to begin rebuilding his alliance network, however, signing a pact with the Emir of Tunis that revived their old friendship.

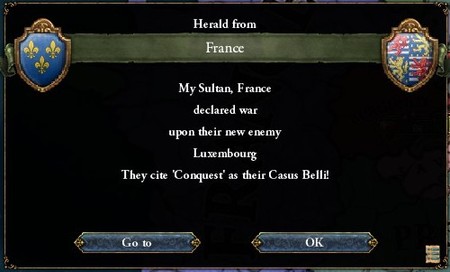

As for France, the defeat of its Iberian rival obviously hadn’t been enough, because King Dávi had embarked on a series of expansionistic wars against an array of Dutch and German princes.

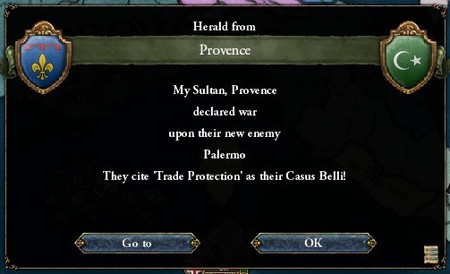

In Palermo, on the other hand, a crisis erupted following the sudden death of the Emir. In parallel to their cousins across the Mediterranean, two rival branches of the Palermo Jizrunid family quickly tore the emirate apart as a vicious civil war broke out.

Eager to expand their influence over north Italy, Provence chose this moment to pounce, declaring war on the Muslim Emirate even as it descended into civil war.

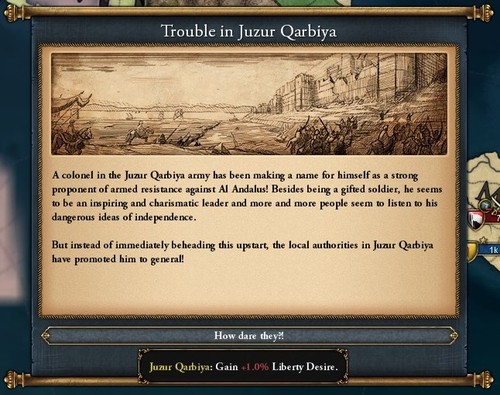

It wasn’t much longer before Al Andalus had its own crisis to deal with, however. Across the Atlantic Ocean, in one of the many rich islands making up Juzur Qarbiya, aspirations for more autonomy had been quickly escalating into ambitions for independence.

These ambitions came to a head late in 1690, when Muqti Muhammad of Juzur Qarbiya blatantly refused a direct command from the Majlis to arrest one of his more influential generals.

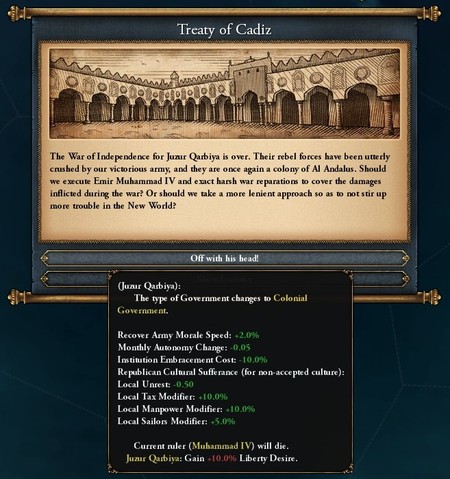

And it didn’t stop there, because the Muqti quickly followed that up by raising an army of his own, and in a short address to his colonial assembly, declare his independence from Qadis and Iberia.

Now, Juzur Qarbiya may have been very rich, but they weren’t exactly populous. Al Andalus could have easily quashed the insurrection, so long as they were facing Juzur Qarbiya alone.

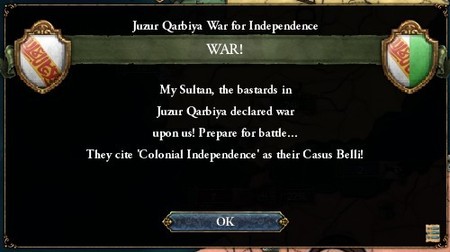

But they weren’t alone. The Muqti had already managed to negotiate an alliance with the Almoravid Sultan of Morocco, dragging him and all his colonies into the independence war as well.

With that, Al Andalus and Morocco were finally in direct conflict with one another, after long centuries of tension and rivalry bubbling between the two neighbours, powers that had once been the closest of allies.

The Majlis wasted no time in gathering its bearing. With Salma Hisham now serving as governor of Ibriz, they appointed the young but talented Umar ibn Idris as the new Supreme Commander of the Andalusi army, numbering 25,000-strong. Umar had fought in the Fitna as one of al-Muhsin’s generals, quickly proving himself an adept commander and innovative tactician.

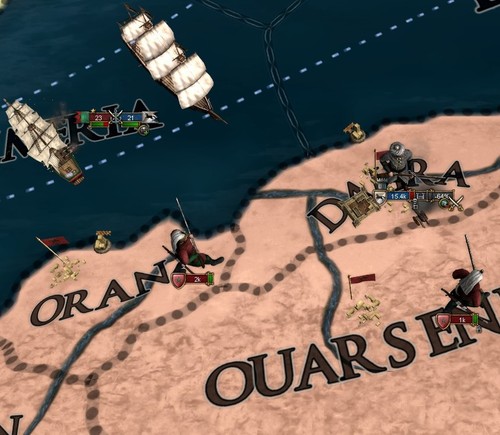

The primary problem facing the Majlis wasn’t the army, however, it was the lack of a navy. Another consequence of the Fitna had been the utter destruction of Andalusia’s war fleet, leaving the Majlis helpless as the Almoravid Navy quickly seized control of the Straits of Gibraltar, giving the Moroccans access to Qadis itself.

Within a few weeks, news of the war had spread throughout Gharbia, with Juzur Qarbiya and Morocco’s Caribbean colonies launching a coordinated invasion of northern Ibriz.

The Muqti of Ibriz – Salma Hisham – quickly took charge of the colony’s defenses, shipping a 15,000-strong army across the Bay of Mexica and rushing to engage the invaders before they could capture any fortresses.

The ensuing battle was a close encounter, but Salma managed to come out on top, forcing the Qarbiyan army to retreat before pursuing and crushing it.

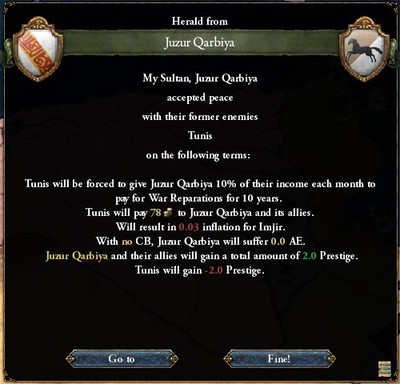

Back in the old world, on the other hand, the Tunisian army was decisively crushed in the hills of Algeria, surrounded and annihilated after just three hours of fighting.

The Almoravid sultan followed that up by sending his forces to besiege Tunis itself, capturing and sacking the rich trading city after a short siege. And with his army destroyed and capital lost, the Emir of Tunis was forced to bow out, defeated less than a year into the war.

In the new world, the Moroccans and Qarbiyans launched another invasion, this time attacking Ibriz’s core territories in central Gharbia.

Salma Hisham managed to slip past the Moroccan blockade with a fleet of thirty transports, however, landing his army at Belize and quickly marching to engage the invaders.

The Qarbiyan rebels were the first to meet with Salma, and with no hope of reinforcement, their lines quickly began to falter before shattering. With nowhere to retreat to, Salma Hisham managed to pin them down again a few weeks later, wiping the remnants of the army out altogether.

In the north, meanwhile, the Moroccan army had clashed with a massive uprising of native Mayans. The battle was fought just below the walls of Andalusi-controlled Petén, with the numerically-superior rebels prevailing after a bloody fight, both sides suffering heavy losses.

Salma Hisham, always one to take advantage of another’s misfortune, pounced on the Mayan separatists just days after their defeat. Their ranks weakened and morale shattered, the rebels didn’t last long, surrendering after a few hours of heavy fighting.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, an opportunity for Umar ibn Idris to prove his worth finally arose.

After patrolling the Straits of Gibraltar for almost two years, the Almoravid Sultan finally sent an army to test the defenses of Qadis, with the 17,000-strong expedition led by his own son and heir.

Supreme Commander Idris seized the initiative and pounced on the opportunity, attacking the Moroccan force within hours of its landing in Algeciras.

The battle was initially hard-fought, with prince Agdun putting up formidable resistance. Slowly but surely, however, Idris managed to employ an ingenious tactic in which the Morrocans were drawn further and further inland, before outflanking and surrounding the entire army.

Thousands were slaughtered over the next few hours, and thousands more were taken prisoner, including the Almoravid prince Agdun himself.

With that, the Andalusi had managed to land a stinging blow to the pride and prowess of the Almoravids. Still, however, it wasn’t enough to secure a favourable peace from Juzur Qarbiya.

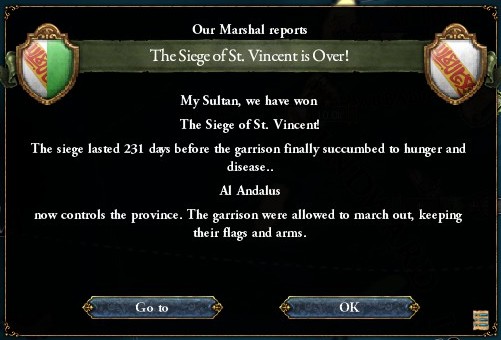

Salma Hisham, on the other side of the world, knew that the only way to do that was by capturing the rebel capital. So after securing the rest of Ibriz, he began formulating a new plan…

By sticking close to the coast and fleeing upon sight of any Moroccan vessels, Salma Hisham managed to slowly guide his entire army eastward, landing on the beaches of the Qarbiyan capital just weeks later.

Juzur Qarbiya was apparently ridden with internal turmoil, but Salma Hisham managed to crush any resistance and besiege the Qarbiyan capital. The well-stocked city held out for months, but Salma managed to capture it after a daring night-time assault, quickly seizing and capturing Muqti Muhammad as he did so.

And with the Qarbiyan capital captured and the Muqti in chains, the War of Juzur Qarbiyan Independence came to a decisive end, after three years of battle in the new world and old.

The rebellious Muqti Muhammad was transported to Qadis in chains, where the Majlis sentenced him to death after a mock trial.

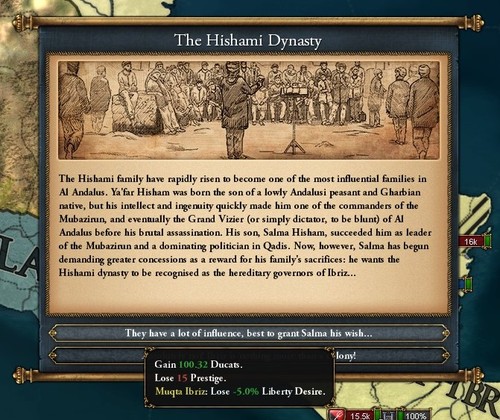

The war was not yet over, however, not truly. A few days after the rebellious governor was beheaded, Salma Hisham reached out to the Majlis, demanding a… reward for his own efforts during the war, as well as the sacrifices his father had made during the Fitna.

And there was only one thing he wanted – for his family to be granted hereditary governorship over Ibriz.

The Majlis was divided over whether or not the Hishami should be granted the colony – Ibriz was vast, controlled immense gold mines, and would only become more powerful as the years slipped past. Sultan al-Muhsin in particular was opposed to the notion, perhaps fearful over another dynasty rising to power.

Refusing Salma might have precipitated another war of independence, however, and the Majlis was desperate for some peace. So after a short assembly, they agreed to grant the Muqta of Ibriz to the Hishami family.

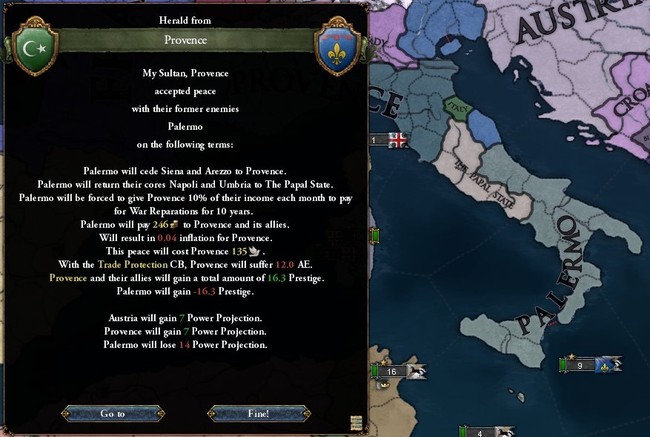

In the east, meanwhile, another Jizrunid war also came to an end. Despite fostering a close alliance with the Vakhtani Caliphate, Palermo was unable to repel a combined invasion from Provence and Bavaria, and was forced into surrendering its north Italian holdings.

The Sultan and Majlis were no longer concerned with the troubles of Palermo, however. The lords of the Majlis were devoted to the gradual economic recovery, whilst Sultan al-Muhsin spent his days tackling the rising tensions between his Sunni and Shia subjects. Late in 1684, he presented a bill to the Majlis in which all Muslim sects would be granted equal rights, freeing them from any Jizya payments.

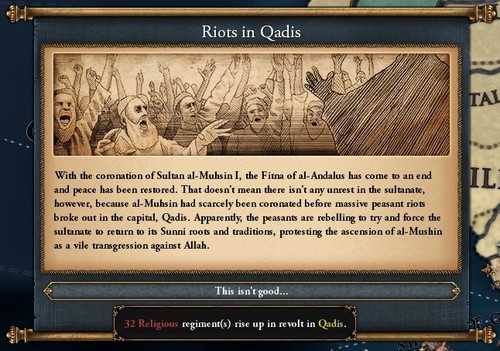

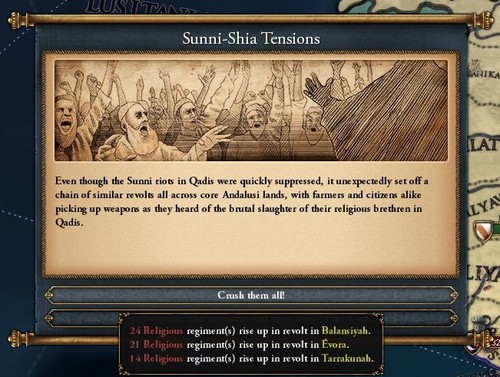

This wasn’t exactly met with a positive reception amongst the Sunni peasantry, however. Perhaps insulted by the Shias being granted equal status, another zealot firebrand managed to rouse the populace of Qadis into a sudden riot, with thousands of peasants marching on the Majlis Assembly hall.

The Andalusi Army was quickly summoned to quell the riots, but just as they arrived in the city, the Majlis was met with much worse news…

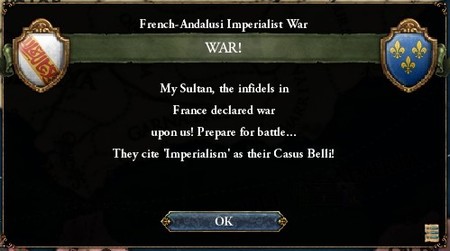

War with France.

And this time, Al Andalus would stand alone, as the war-weary Emirate of Tunis broke off their ties with Iberia.

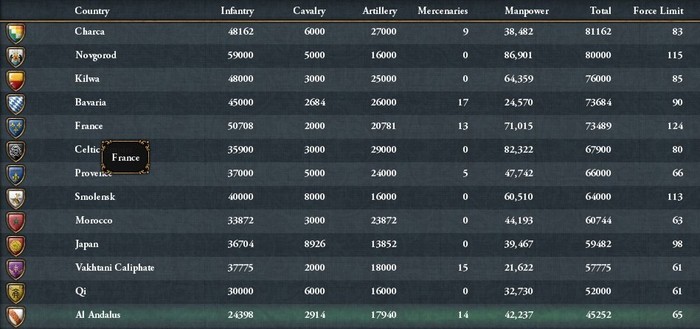

The prospects were not looking good for Al Andalus, which had a standing army of just 45,000 men, divided between Iberia and Ibriz. France, on the other hand, commanded the strength of 70,000 men-under-arms, along with the latest guns and cannons.

The Majlis’ first order of business was thus to gather the entirety of its army, quickly commanding Muqti Salma Hisham to provide transportation for the colonial forces, which made their landing in Galicia a few months later.

Unfortunately, just as the two armies joined up a few miles north of Qadis, word reached the capital of more revolts. Apparently inspired by the riots in the capital, a string of Sunni uprisings broke out all across Al Andalus, led by radical Sunni clergymen calling for the overthrow of the Jizrunids and installation of a theocracy.

First things first, Supreme Commander Idris quickly combined his armies, before leading them south to finally suppress the riots in Qadis.

With permission from the Majlis, thousands of peasants were indiscriminately slaughtered over the space of a few hours, with the streets running red before day’s end. The rebel leaders were then gruesomely tortured, a terrifying tactic that Idris hoped would dissuade any further riots.

Once the capital was thoroughly purged of rioters and rebels, the Supreme Commander began a massive recruitment drive, training hundreds of untested soldiers in the manoeuvring and operation of artillery – which the Andalusi army was in dire need of.

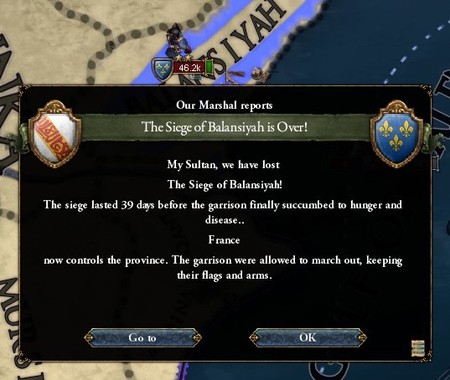

Before their training could be completed, however, the French launched a massive invasion of Iberia and laid siege to Saraqusta, the gateway into Al Andalus.

The Supreme Commander thus struck out, engaging a 15,000-strong force in Rioja, hoping to the lure the French into breaking their siege on Saraqusta.

The battle of Rioja itself was a resounding success, the vast majority of the French army either dead or captured after a few hours of close fighting, with relatively negligible Andalusi losses.

Unfortunately, whilst battle was raging towards their west, the larger French army had managed to breach the walls and capture Saraqusta.

The 40,000-strong French force then leapt southward, hoping to reinforce the fight at Rioja, only to miss it by a few hours. They managed to pin down Idris’ army as he retreated from the bloody battlefield, however, forcing the Andalusi to commit every man with the faint hope of somehow prevailing.

It was not to be, however. Even though the Andalusi were able to inflict far greater damage than they took, sheer numbers forced them to fall back from the battle, surrendering their position in Majrit.

With thousands already dead, the Majlis was forced to take out several loans, despite its decade-old debts still weighing heavy. They had little choice, however, with the only other option being to simply surrender.

This coin was used to quickly recruit more mercenaries, with more than 20,000 German and Italian soldiers shipped over from Provence.

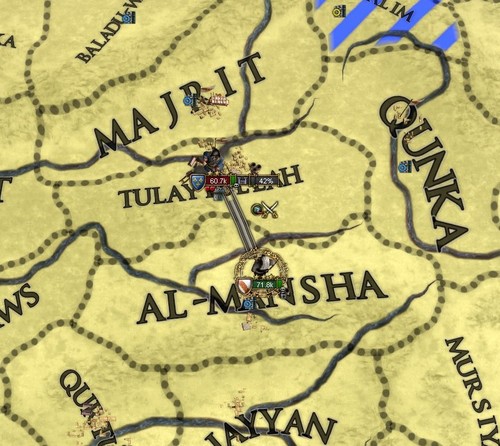

With the Andalusi army suddenly doubled in size, Supreme Commander Idris pushed north on a forced march, engaging the swollen French force besieging Tulaytullah.

Once more, the French proved themselves tenacious fuckers, inflicting devastating damage to the Andalusi centre in the early hours of the battle. Idris managed to use his superior numbers to outflank the French, however, desperately using every trick in the book to come out on top.

And when the battle came to an end a few hours later, it was the Andalusi who stood triumphant, with the French fleeing northward with all the haste they could muster.

Determined to capitalise on his victory, Idris marched north on another campaign before the week was out, besieging Saraqusta with his cannons while the rest of his forces guarded the mountain passes of Navarra.

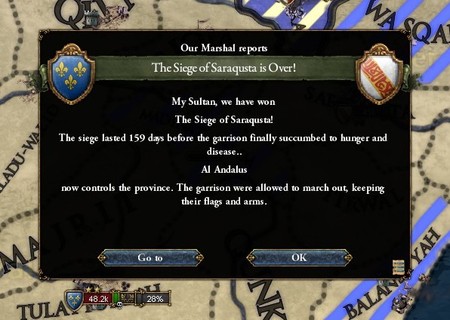

Whilst the western passes were secured, however, the French were able to slip back into Iberia through Roussillon. With an army numbering 45,000 soldiers, the French quickly marched down the coast and lay siege to Balansiyyah, capturing the city just one month later.

Saraqusta held out for a few weeks longer before capitulating to Idris, but the siege had already lasted far longer than it should have, so there was little cause for celebration.

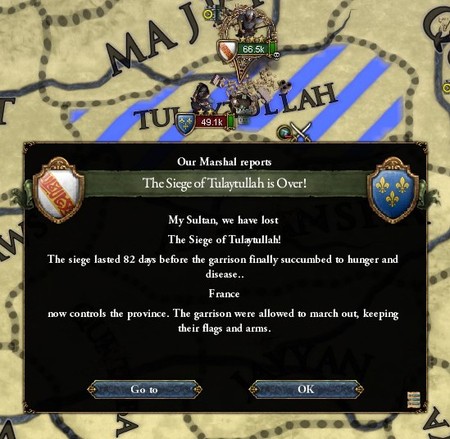

In fact, whilst the Andalusi were busy trying to breach Saraqusta's walls, the French had managed to swing westward and capture Tulaytullah in a lightning offensive. Supreme Commander Idris tried to push south and relieve the city before its fall, but he was a few hours too late.

All the same, he engaged the French army beneath the walls of the City of Sultans, throwing everything he had at the enemy. And though the Andalusi sustained a fair few losses, they managed to prevail once again, scoring another important victory.

Once again, however, it was one step forward, two steps back. Whilst the battle of Tulaytullah had been raging, another French army had descended from the Pyrenees and re-captured Saraqusta, this time after a siege of just 59 days.

Both Idris and the Majlis were growing more desperate with every passing day, despite winning almost every battle, they were undoubtedly losing the war.

As Andalusi forces pushed northward to try and relieve Saraqusta, the French flooded into southern Iberia, capturing and pillaging everything from Barcelona to Qurtubah.

To add to that, the French vastly outnumbered Andalusi forces, so Umar ibn Idris was forced to resort to ambush tactics.

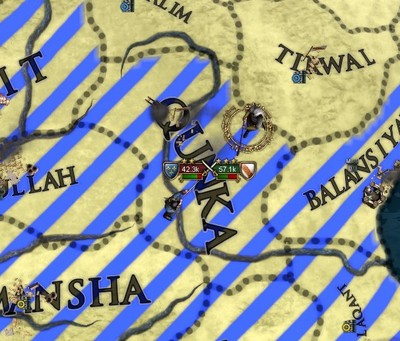

So he took up a position along the eastern Iberian coast, and when a 45,000-strong French army was sighted marching northward, he quickly managed to lure them into the hills of Qunka.

With the element of surprise on their side, the Andalusi massacred the French army, gunning down almost 20,000 men in the rolling green hills of Qunka. The remnants of the French force managed to escape just as dusk gave way to night, but the Andalusi victory had already been secured.

Euphoric after the decisive battle, Supreme Commander Idris began another offensive northward as soon as possible, rushing to engage an isolated French army near Saraqusta.

The numbers were roughly equal, but the French had learned from the massacre at Qunka, and were able to expertly repel all of Idris’ usual tactics. They sustained heavy losses, but the French were eventually able to throw back the Andalusi attack, forcing them to retreat westward.

Not long later, Sultan al-Muhsin received word from Gharbia, where Ibriz was beginning to strain under the constant war. Salma Hisham requested reinforcements to keep French colonial forces at bay, but with his resources already stretched thin, the Sultan was forced to refuse.

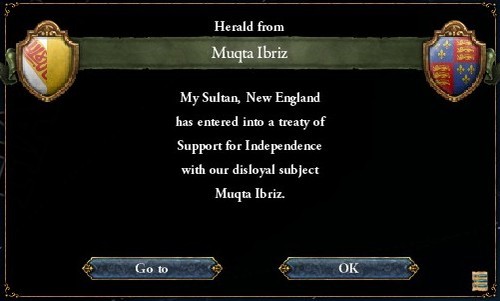

And the Muqti of Ibriz didn’t take that too well. Salma began to reach out to the King Edward Butler of New England, initiating a series of meetings that ended with an alliance between their two powers.

This proved to be the final straw. Half of Iberia was under brutal foreign occupation, the Andalusi army was shattered and in full retreat towards Galicia, the sultanate was steeped in debt yet again, and now the threat of war with Ibriz was on the horizon…

So the Majlis began making overtures for peace, and were about to meet with the French to discuss the terms for surrender when everything changed…

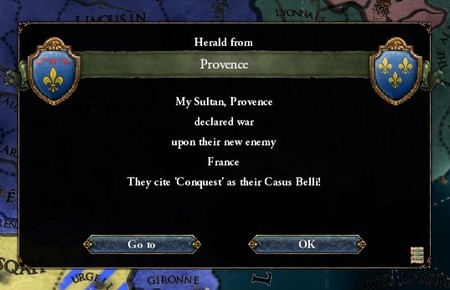

Apparently seeking to curb King Dávi’s rapid expansion, Provence had declared war on the Kingdom of France, calling on its allies in Bavaria and the Celtic Empire to join as it did so.

And just like that, France as now surrounded by enemies.

This was an opportunity for Al Andalus to strike back, hard and fast, and the Majlis knew it. So more loans were quickly taken out from Provencal banks, and the Andalusi army was reinforced with more mercenaries.

Once he’d recovered, Supreme Commander Idris took personal charge of the army once again, pushing eastward and engaging a French force besieging Qila.

Obviously surprised by the sudden recovery of Andalusi morale, the French were quickly defeated in a short engagement, with almost half their men killed or captured by day’s end, and the rest fled back to France.

With that defeat, King Dávi pulled back the rest of his armies to focus on Provence and Bavaria, allowing the Andalusi to quickly spread out and recapture large stretches of occupied territory.

At the same time, however, Majlisi spies in Paris reported that King Dávi had begun a monumental recruitment campaign of his own. Determined to crush his European rivals, the king had managed to amass an army that numbered beyond 100,000 soldiers, larger than any one of his rivals.

The bulk of these numbers suddenly descended on a much smaller Andalusi army that had been stationed in Navarra, forcing Idris to once again throw together every man he could muster.

Despite inferior numbers, the mountainous terrain of Navarra combined with Idris’ novel tactics proved to be enough to at least stifle the French advance, with the battle quickly grinding down into more of an endurance test.

And this time, it was the Andalusi who came out on top, forcing the French to withdraw from the mountain pass after almost an entire day of thick, bloody fighting.

Shortly after the victory, morale was furthered buoyed by the capture of Saraqusta, finally bringing all of Iberia back under Andalusi control.

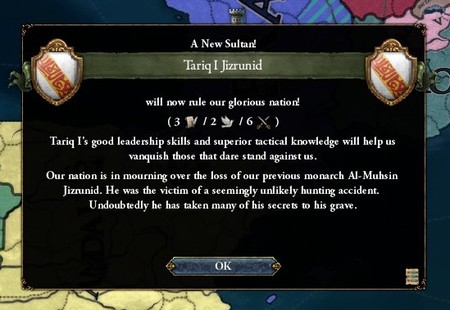

This string of victories came to a bittersweet conclusion, however, with the sudden death of Sultan al-Muhsin.

Apparently, the old man had been hunting when his horse threw him from his saddle and down a cliff, leaving everything below his waist gruesomely torn apart. The doctors could do nothing to heal such horrendous injuries, except to make the Sultan’s passing easier.

Despite his rather undignified end, al-Mushin would be remembered fondly by later generations, a rare occurrence amongst the Jizrunids.

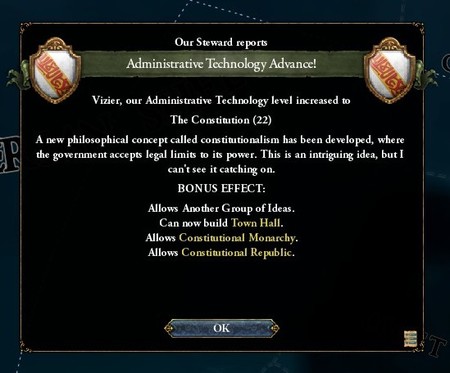

He would be remembered as the man who had restored the Tariqi branch of the Jizrunid dynasty, who had brought about an end to the Fitna of al-Andalus, who had served as the first Shia Sultan of Iberia, who had helped begin the era of constitutionalism…

So it isn’t much of a surprise that al-Muhsin’s death was met with grief from many across Al Andalus, with his eldest son Tariq succeeding him as sultan.

Still, however, Al Andalus is embroiled in conflict. The coronation of Tariq brings the war to a standstill, as the new Sultan prepares to open a new session of the Majlis, convening the first official parliament assembly in decades.