Part 56: The Golden Age of Al Andalus, Part 2

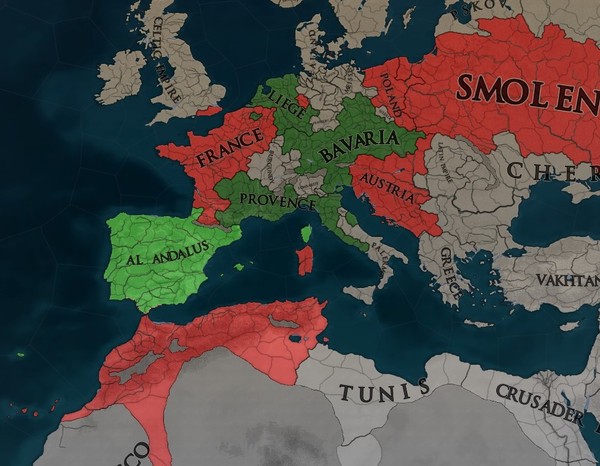

Chapter 24 - The Golden Age of Al Andalus, Part 2 - 1745 to 1753Europe and North Africa, 1745.

Al Andalus was facing enemies in every direction, from France and Morocco in the north and south to the young rebellious states in the far west. Bavaria was Iberia’s only ally in the grinding war to come, but their help could not be relied on, not whilst the Archduchy was still embroiled in a conflict of its own, invading Austria’s Balkan holdings with the support of Provence and Liege.

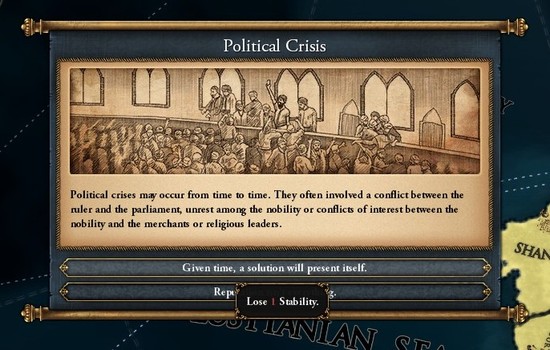

Unsurprisingly, Qadis had erupted into chaos upon the declaration of war, with everyone from aristocrats to politicians to commoners breaking down into hysteria. All were convinced that Andalusia’s chances of coming out victorious were slim to none. How could they believe otherwise, when the sultanate was up against some of the largest and most powerful empires in the world?

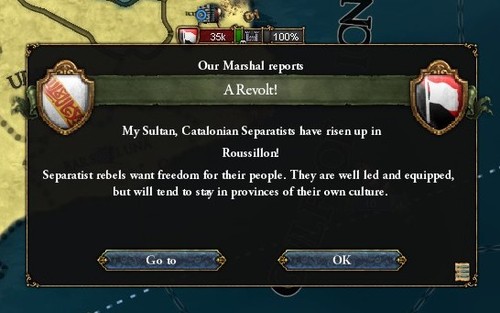

And the war wasn’t the only crisis the Majlis was facing, because news of separatists and rebels had begun trickling into the capital shortly afterwards. This didn’t come as much of a surprise - Iberia was a fragile canvas of rivalled religions, differing customs and volatile cultures, and all it took was the slightest turbulence to cast the entire peninsula into civil war.

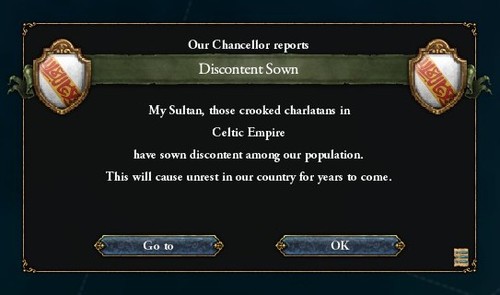

Of course, Andalusia’s rivals didn’t help the matter. Not only were France and Morocco jointly planning an invasion of Iberia, but the Celtic Empire followed them up by shipping huge amounts of guns to insurgents throughout the sultanate.

With all that said and done, however, Tahir ibn Yahaff was still confident. Unsettlingly so, even, the ageing politician was convinced that he could hold off both the Berbers and the French long enough to separate peace them, before leading the Andalusi army across the Pacific to personally crush the Gharbian revolutionaries.

The Grand Vizier didn’t exactly have a penchant for battlefield tactics, but his mind was as sound as ever, and he managed to unite the lords of the Majlis as he began planning for the oncoming war.

Obviously, any progress in the arts or cultural development was quickly brought to a standstill. Every last dinar had to be directed into the army, so new palaces and mosques were left half-finished, construction on roads and other public works were halted, the painters and writers crowding the royal court were dismissed, and the crown even began accepting donations from noble families.

To put it bluntly, Grand Vizier Tahir took money from wherever he could get it.

The influx in cash was immediately funnelled into the army, which swelled from 60,000 to over 80,000 men-at-arms, along with the latest in guns and artillery. Even that didn’t seem like it would be enough to keep the Almoravids alone at bay, however, with Andalusi agents reporting that over 100,000 Berbers were massing along the straits of Gibraltar.

By then, almost a year had passed since the declaration of war with neither side making the first move. As winter began to approach, the Moroccans finally took the plunge and pushed across the Straits of Gibraltar, marching straight towards Qadis. The nobles of the Majlis was already escorted out of the city, of course, relocating to the northern capital of Tulaytullah, along with any other persons of note.

From the relative safety of Qurtubah, meanwhile, Vizier Tahir commanded Andalusi forces to go on the offensive and intercept the Moroccans before they could begin firing on the capital.

Not very eager to fight a battle on ground they didn’t know, the Berbers eventually decided to back down, fleeing back across the straits. The Andalusi were not left without a prize, however, pinning down a small Qarbiyan expeditionary force and annihilating it.

Encouraged by these early successes, Grand Vizier Tahir decided to chance a riskier manoeuvre. He kept personal command of his forces and handed the other half to his Supreme Commander, Ahmad Karima, with orders to scout southern France and prepare for an invasion.

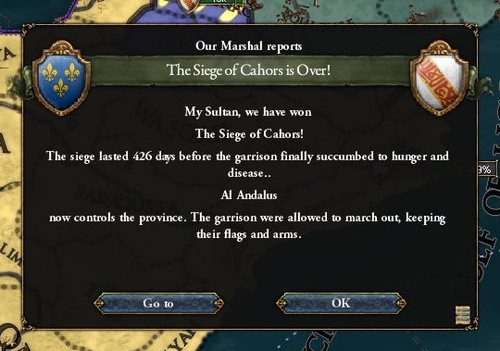

Blinded with dreams of glory and grandeur, however, Karima decided to march straight for the strong regional fortress of Cahors and lay siege to it. This, without any hopes of forcing a breach or starving them out, and a hundred miles away from the nearest reinforcements.

As a fool could have predicted, the French pounced on the chance to attack an isolated Andalusi army, striking south and engaging Karim’s forces within days. The French were superior in numbers and morale, so it didn’t take long before the battle turned against the Andalusi, who were forced to cut their losses and retreat after four hours of thick fighting.

And the humiliation didn’t end there, because whilst en route towards Tulaytullah to report to his failure to the Grand Vizier, word reached the Majlis that Ahmad Karima’s forces had attacked and sacked a string of Aragonese cities - cities under the domain and protection of Al Andalus.

Karima would later claim that he had simply been suppressing nationalist rebels, but by then, it was far too late. Grand Vizier Tahir relieved him of his command, and after a short and one-sided trial, the former Supreme Commander (and self-titled Conquerer of the Aztecs) was executed.

The damage had already been done, unfortunately, and both the peasantry and aristocracy of northern Iberia were beginning to stir. Early in 1747, the first of many rebellions broke out in Roussillon, with almost 40,000 separatists rising up and demanding the formation of a Muslim Catalonia - Qattalun.

Roussillon was defended by a powerful citadel, fortunately, and it would take months, if not years, for the rebels to capture it.

Still, however, Grand Vizier Tahir couldn’t react by doing nothing - he had to act, and now. So, perhaps using the very same strategy employed by Karim (and no doubt taking credit for it), the Grand Vizier pushed north with all the strength of the Andalusi army and crossed the border into France.

This time, with 80,000 Andalusi bearing down on Cahors, the French were not so eager to engage them, instead launching an invasion of their own into Bavaria. The stalwart fortress was still as unyielding as ever, unfortunately, with its sturdy walls and wary guards holding out for over a year before finally succumbing to the Andalusi.

The small winter town within Cahors was mercilessly sacked over the next few hours, of course, with Tahir installing a new garrison once the burning and looting had settled down.

With a buffer now separating the French army from the Iberian peninsula, the Andalusi could push south again without worry of a sudden invasion from the north. Grand Vizier Tahir, determined to maintain internal stability, immediately began marching towards Roussillon and the separatist rebels.

The battle went as best as the rebels could have hoped for: long, hot and bloody - but ultimately with only one victor.

Or so they thought.

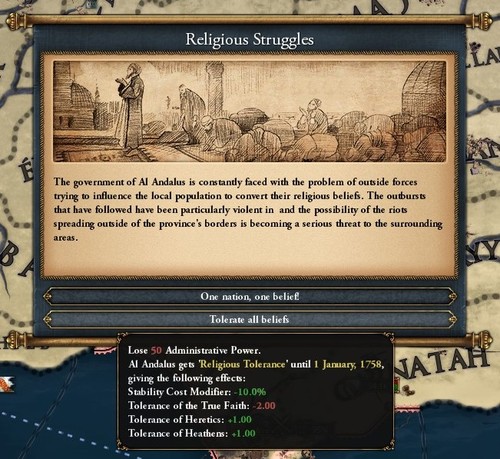

You see, as the eighteenth century forged ahead, separatism was not the only movement plaguing Iberia. Once upon a time, it had been a simply case of Andalusi Muslims versus the northern Christians, but it wasn’t so straightforward these days, and Al Andalus was nowhere near as united as it had once been. Now an even greater crisis was beginning to surface, one that had been on the horizon for years and decades, but one that the Majlis had never tried to resolve.

Religion.

It had been centuries past when the Majlis had decided that, rather than forcing Islam on the local populations, they would tolerate heathen faiths and foreign cultures. And since then, it had appeared to work out fine, apart from the relentless revolts in Castille.

Things had begun to change when Al Muhsin rose to become the Sultan of Al Andalus, however, seating a Shia on the throne for the first time in the history of the sultanate. The firmly-entrenched Sunni clergy and populace were not happy, and they were beginning to show it.

The trigger, as it happened, was nothing to do with religion at all. The unrest had always been there, of course, the uneasiness and tumult and anger was all just waiting to burst out at the slightest provocation - and that provocation arose late in 1747, when famine struck Iberia.

Grand Vizier Tahir had been so engrossed in strategy and tactics, dedicating every moment of his day to the war, investing every last coin into the military, that he had overlooked his own duties as vizier of Al Andalus. And the people of Iberia would pay for his mistake, with half the peninsula starving before the year was out.

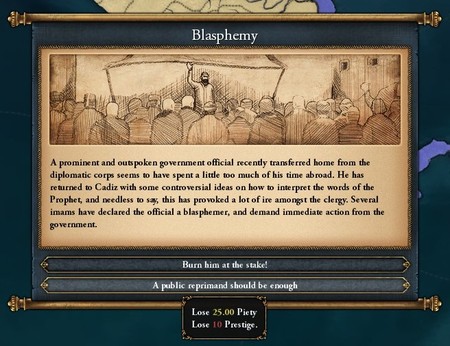

The Famine of 1747 - causing the deaths of tens of thousands of innocents - would become the historic opening of almost a decade of utter chaos in Iberia. Not only were the masses being ruled by a heretic that had stripped the clergy of their power, but now they were not being fed either, and there is no surer way to cook up a disaster than to starve the peasantry.

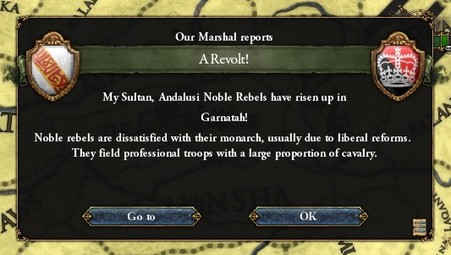

To begin with, the revolts were not of a religious nature, with almost everyone who could get their hands on a gun rising up in street brawls and mob riots. The only organised revolts that opened 1748, however, were a couple noble rebellions in Gharnatah (angry at the Sultan for letting the Majlis accumulate so much power) and large particularist uprisings in Tulaytullah and Qadis (who blamed the food crisis on the Majlis).

Even as the first cracks began to show, however, Tahir was forced to focus on the war in the south. The Moroccans - no doubt aware of the turmoil in Al Andalus - chose this moment to cross the straits again, marching towards Qadis under cover of night and laying siege to the city less than a day later, with artillery blowing its walls apart before long.

The Grand Vizier appointed a new Supreme Commander to lead the Andalusi armies, a talented tactician by the name of Ismail Wannaqo. The Wannaqo were a noble family with decent estates and a seat on the Majlis, but the Grand Vizier wasted no time in warning him of the consequences should he fail to relieve the siege.

This was the first meeting between Jizrunid and Almoravid in decades, and from its very outset, the battle was not in favour of the former.

Amir Wannaqo used every trick in the book, from cavalry charges to shock reinforcements to false retreats, but his opponent on the other side of the field was his superior in every respect. Andalusi discipline was certainly better than that of the Berbers, but every Almoravid soldier seemed to fight with the strength of two men, forcing the Andalusi line back step-by-step as the day progressed, despite taking heavy losses of their own.

Andalusi formations were on the verge of breaking apart when Wannaqo’s saving grace arrived - another 30,000 men. Upon sighting the well-rested reinforcements, the Berbers finally gave up the battle and broke from the field, with the Andalusi chasing them all the way back to the beaches of Jabal Tariq.

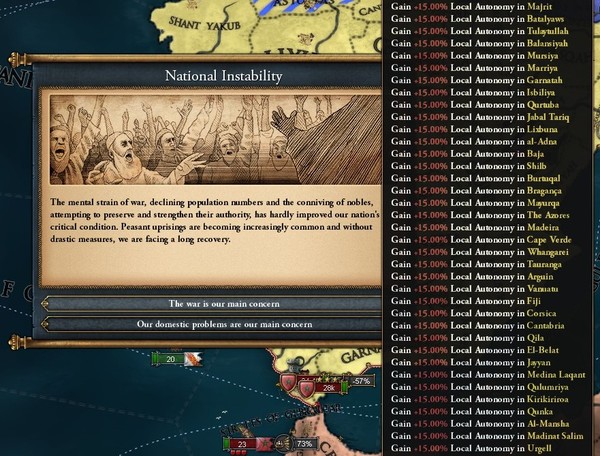

Of course, the short siege had only worsened the famine crisis escalating all across Iberia, and unless something was done about it soon half the country would be in open rebellion. So the Grand Vizier was forced to take a drastic step. Keeping his full attention on the war, he delegated huge responsibilities and autonomy to the local emirs and sheikhs dotting Al Andalus, trusting them with everything from provincial defenses to local finances - more power than they had held since the Early Medieval Era.

A desperate measure, but as Tahir would have insisted, a necessary one as well.

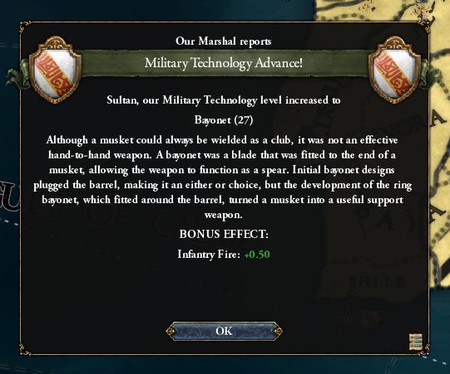

Some good news did arise a few days later, and the Majlis were in sore need of any good news at all. A few Moroccan guns from the battle of Qadis had been salvaged and dissected, with Andalusi engineers taking them apart and drawing up new designs within weeks.

It would take months to produce these new weapons and bring them into circulation, of course, but hopefully it would put the Andalusi on a more even playing field with the Moroccans the next time the two foes met.

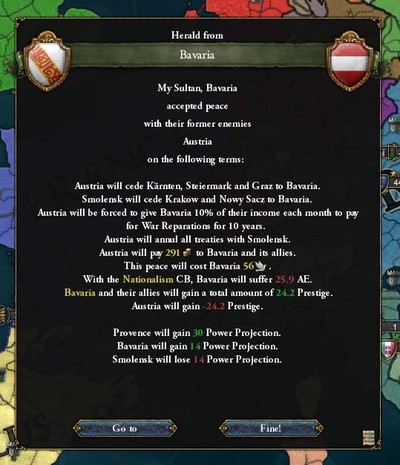

This was immediately followed by another promising development - after a grinding war in eastern Europe, the Archduke of Bavaria had finally concluded a peace with Austria and Smolensk. His army had taken a big hit during the war, and large parts of western Bavaria was under the occupation of French forces, but Grand Vizier Tahir hoped they’d be able to push back against the French and begin pulling their weight in the conflict.

With the French embroiled in Bavaria and the Moroccans temporarily thrown back, Tahir could look inward once more. Receiving urgent requests for aid from countless sheikhs, he sent Andalusi forces northward to begin quashing the many rebellions that had sprouted up over the past couple years.

Still under the supreme command of Ismail Wannaqo, the Andalusi army began by engaging the forces of one Muhammad Yahaffid, a zealous Sunni emir who’d thought he could overthrow the Jizrunid dynasty with 25,000 mercenaries. It took less than three hours of fighting for the mercenaries to defect en masse, leaving their emir to be captured and executed, ending his rebellion on the spot.

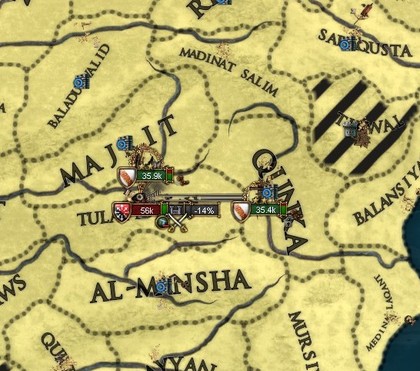

The Andalusi then pushed westward towards Tulaytullah, where the Majlis assembly itself had come under threat as almost 60,000 starving peasants, fickle mercenaries and deserting soldiers attempted to seize control of the city. They were cut down in their tens of thousands as the barren plains surrounding Tulaytullah drank up the spilt blood, leaving a mountain of rotting flesh in their wake.

Once the northern capital was secure, Grand Vizier Tahir directed the Andalusi army south again, where the Berbers had crossed the straits and besieged Qadis again. And this time they weren’t wasting any time, focused on breaching the outer walls of the city before any relief could arrive.

Before the Supreme Commander could engage the Moroccans, he led his forces to crush a minor revolt in Granada. The Majlis were finding it increasingly difficult to pay and sustain such a large force, however, so the Grand Vizier gave the Andalusi army free reign to ransack and burn the historic city once the battle was won.

By now, the combined professional and mercenary forces making up the Andalusi army were growing increasingly irritated at the lack of pay - and that’s putting it lightly. Still, every single soldier would be needed to face down the 65,000-strong Berber force besieging Qadis, so Vizier Tahir promised them huge bonuses if they kept their guns loaded and raised for a few months longer.

And so, with a slight advantage in numbers but a big hit to morale, Supreme Commander Wannaqo led the Andalusi into the second battle of Qadis.

Once again, the battle was a close-cut affair. The Berbers took heavier losses throughout the fighting, but their discipline and morale ensured that their square formations stayed rigid and firm, adamantly depriving the Andalusi of any weak points or line breaches.

The fighting raged all around the city for almost an entire day, with the Moroccans determined for a chance at sacking Qadis and the Andalusi determined to prevent it.

The turning point came towards the end of the day, when lines along both ends of the battle began faltering. Ismail Wannaqo chose this moment to send a rider into Qadis, ordering the city guard to orchestrate a sortie and hit the Berbers from behind. The move was executed to perfection, and for the second time in the war, the Moroccans were chased back across the straits with heavy losses.

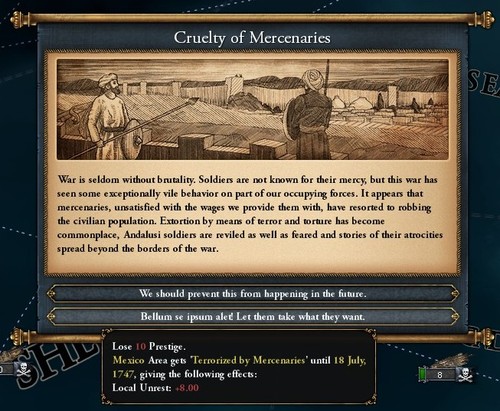

Grand Vizier Tahir ordered huge celebrations to be carried out in all major cities (or those he still controlled) in honour of the historic victory, whilst quietly disbanding almost all of his mercenary forces whilst everyone was distracted. The mercenaries were dispersed by force, but furious at being dismissed without their hard-earned pay, they would surely come back to haunt Al Andalus.

More good news arrived shortly afterwards as the Bavarians scored a huge victory, throwing the French army out of Germany proper. Even with that, however, the war was not exactly going to plan - the revolutionary states across the sea refused to lower their banners, and as long as the Almoravids continued to fight, the Andalusi had no hope of crossing the Atlantic.

The next few months passed in a blur as the two sultanates, separated by a narrow strait, both recovered and prepared for their next bout.

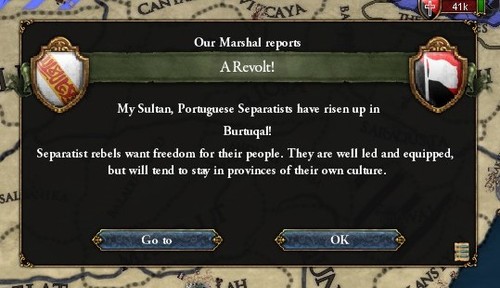

The Andalusi wouldn’t have much time to recuperate, unfortunately, because rebellions had continued breaking out without rest. The latest outbreak was a large Portuguese separatist revolt in Burtuqal, with the rebels quickly storming the weakly-fortified citadel and seizing control of the city.

The merchant ships of the pitiful Andalusi Fleet scurried out of the ports in a hurry, only to be met by the significantly stronger French Navy, which sunk three ships within an hour. Needless to say, the Andalusi fled the battle as soon as they were able.

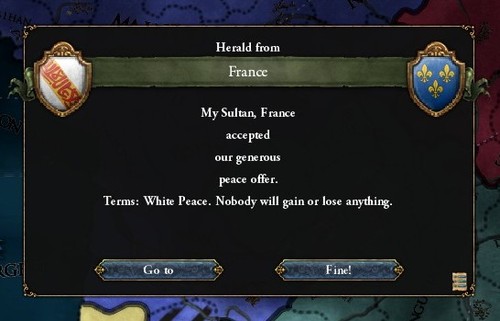

Hoping to wipe one enemy off the maps, the Majlis managed to reach a separate peace with the King of France a scant few days later, with the neighbouring powers agreeing on a status quo. That would hopefully free the Bavarians to deal with the Moroccans - who had apparently invaded the Archduchy’s Italian holdings.

With the French out of the conflict and the Almoravids temporarily distracted, the next few months passed in a blur, with Supreme Commander Wannaqo trekking from Burtuqal to Roussillon to Qurtubah as he crushed rebellions in countless forts, cities and towns along the way.

Still, however, there was always another sheikh who thought he would be the one to topple the Jizrunids, there was always another soldier who thought he could expel the invaders, there was always another peasant who thought he could change the very fabric of the world.

Whilst all this was going on, there were some interesting developments going on in Tulaytullah, where both the royal court and Majlis assembly had relocated for the duration of the war.

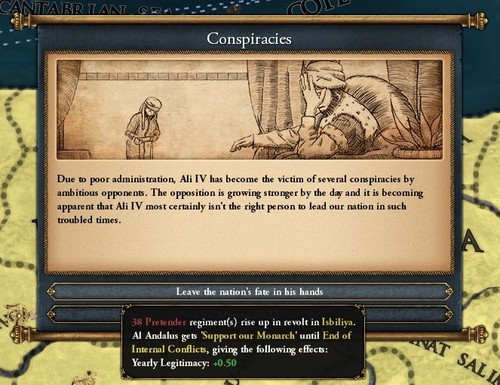

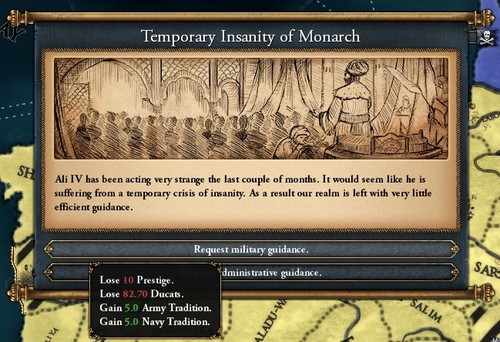

Sultan Ali - who had so far spent his reign in merciful ignorance - was beginning to take an interest in politics. Terrible news, for all involved. Even worse, he had begun to suspect that some members of the Majlis were actually working to weaken the position and authority of the crown, to his immense surprise.

Slowly growing more fearful of conspiracies (and more estranged with his wife), Ali began to grow increasingly… strange. He would fire members of his council at random, kill his servants for no apparent reason, even going so far as to storm into the Majlis assembly and accuse everyone seated of treachery and treason.

Simply put, he seemed to have gone mad.

And in his madness, to the horror of everyone seated in the assembly, Ali commanded his guards to seize Grand Vizier Tahir and throw him into the oubliette. The now-old Tahir warmed his cell for almost a month before being sent to the firing squad, executed without trial.

As has been said, Ali was not a man blessed with intellect, but he was still the Sultan - and that carried weight.

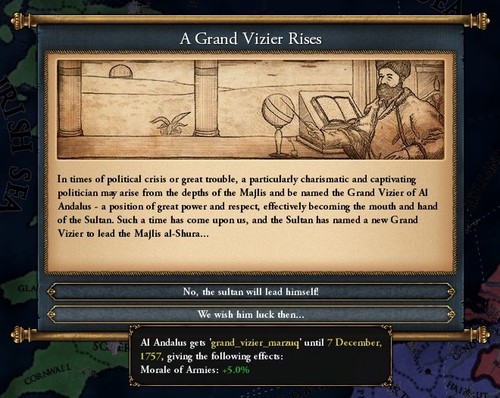

The Sultan appointed a close family friend as Tahir’s successor - Marzuq Aftasid, a nobleman of impeccable lineage. He would serve the interests of the royal family much better, Ali was unwaveringly certain.

Marzuq hailed from one of Andalusia’s oldest and most powerful families, and had more than a passing interest in the military, having been a commander in the army in his younger days.

Unfortunately for him, however, Marzuq’s early days as Grand Vizier were spent pouring over accounts and trying to make sense of all the numbers. Eventually, lost as to how to balance the budget, Marzuq simply opted to take out a handful of new loans from Provencal bankers.

Once that was out of the way, he could finally focus on what he was good at - war. The newly-named Grand Vizier personally led the Andalusi army to Jabal Tariq, where they ambushed a large Moroccan raiding party that had apparently landed during the night.

The battle didn’t exactly go as planned, however. It ended with the Berbers retreating back to Tangiers, which was good, but only after giving as good as they got, with the Andalusi suffering 7000 losses to the significantly smaller Almoravid force.

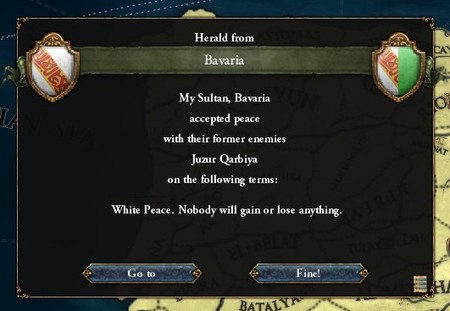

This only gave way to worse news, however, as word reached Tulaytullah that the treacherous Archduchy of Bavaria had secretly met with envoys from the rebellious states and signed a separate peace. They had suffered heavy losses to both the Russians and the French over the past few years, and with the Archduchy now heavily in debt, they weren’t willing to fight the North Africans as well.

A furious Grand Vizier Marzuq sent insults galore to the Bavarian court in Munich over the next few days, hectic and panicked as he struggled to figure out how to proceed.

The Almoravids made the decision for him, sending 35,000 Berbers to lay siege to Qadis for the third time. This was good, very good. An opportunity for the new Grand Vizier to secure a much-needed victory, hopefully galvanising the Majlis behind him as he did so.

It didn’t go as planned.

As was typical, the Moroccans took heavier losses throughout the fight, but still refused to break or balk. This was the third time they were facing the Andalusi beneath the walls of Qadis, and they were much better prepared and ready for any surprises their foe could throw at them. They repelled any attempts at clever tactics, remained wary of any possible sorties, and even brought in some reinforcements to ensure the outcome.

The third battle of Qadis thus ended with the Andalusi on the retreat for the first time in the war, leaving the Moroccans to surround and begin firing at the capital of the peninsula.

To make matters worse, the Almoravids came in with yet more reinforcements over the next few days, quashing any Andalusi hopes of somehow orchestrating a reversal. Another 30,000 Berbers also landed off the coast of Barcelona, immediately pushing south towards Valencia.

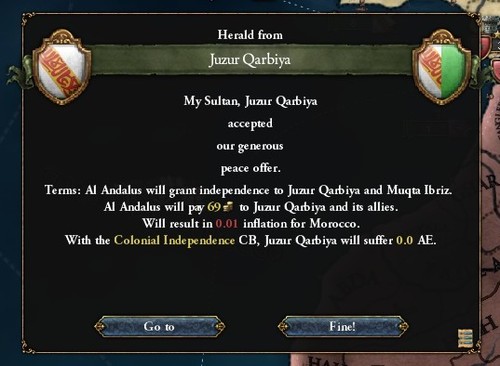

With Qadis now legitimately at risk of being captured and sacked, the time finally came to bring the war to a close. The Andalusi had held out for almost eight years, they fought hard and scored several decisive victories, but they would be remembered as the first kingdom in the old world to lose hold over its colonies.

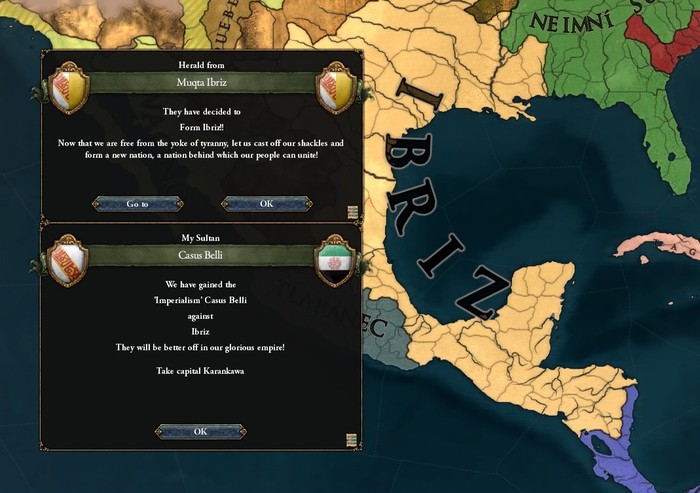

In the new world, a new era was beginning to dawn, and massive celebrations were held all across Ibriz and Juzur Qarbiya. In fact, less than a week after the peace had been ratified, Muhammad Hishami formally crowned himself the "Sultan of Ibriz and all Muslim Gharbia", a title that Sultan Ali had been forced to recognise as part of the peace treaty, in a stupendously expensive and elaborate ceremony.

The young sultanate’s future was bright and hopeful - so long as it can survive its infancy years intact.

In Juzur Qarbiya, on the other hand, the noble families dotting the rich islands opted for an oligarchic republic instead. Power would be shared between a small number of powerful families, with one of their number elected to rule for life - the Qarbiyans were obviously hoping this would lead to more stable transitions of power, likely in an attempt to stave off any Ibrizi plans to annex the islands.

As these western nations begin to look to the future, however, their father is on his knees and in turmoil. Al Andalus has a very long and difficult road to recovery - and with separatists, religious zealots and revolutionaries on the horizon, there is no certainty that it ever will recover.