Part 61: Revolutionary Wars

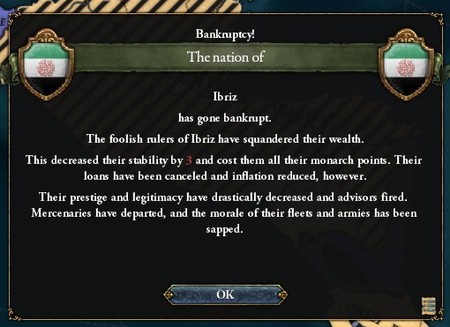

Chapter 29 - The Revolutionary Wars - 1786 to 1799As the eighteenth century rapidly approaches its close and the flames of revolution engulf the world, turmoil reigns from Gharbia to Japan. In the new world, the Hishami Sultanate of Ibriz was quickly collapsing under the pressure of the revolutionaries, forced to take out immense loans in futile attempts to stave off the rebels, attempts that would ultimately come to nothing.

On the other side of the world, meanwhile, the revolutionaries in Japan were eager to export their own ideals. A few months after their wars with the Manchu came to an end, the revolutionary council ruling Japan decided to finally spread the Revolution to the mainland - and where better to start than Korea, a land also ruled by foreign monastic conquerors?

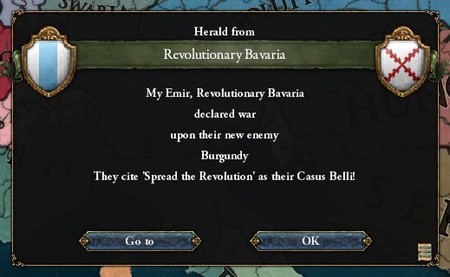

Shifting to the birthplace of the revolution, Bavaria was in utter turmoil as riots and rebellions tore the country apart, with members of the National Assembly lynched and executed every few days. Whilst the people raged and rampaged, however, Grim Torgeir thundered across in Europe on a warpath. He had scarcely made peace with the scattered German duchies, executing their monarchs and installing puppet councils, before looking towards the west. Towards France.

The Bavarian Republic could not take France one-on-one just yet, however. Rather than face the full might of the Sun King, Grim Torgeir decided to pick apart his defenses one by one, by invading and squashing his allies and puppets before turning to deal with Paris.

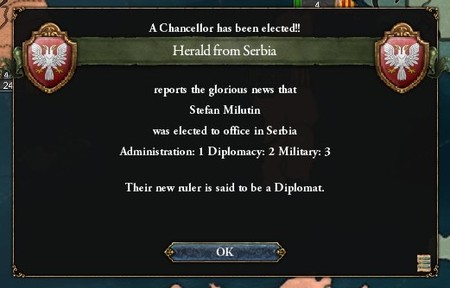

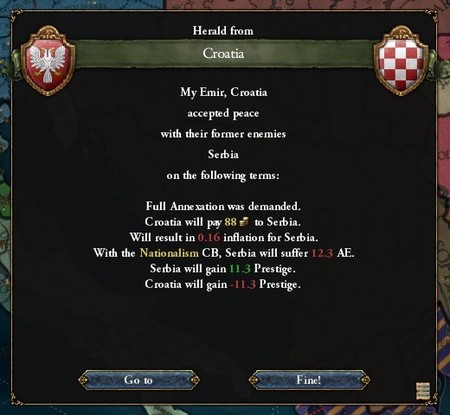

In southeastern Europe, meanwhile, the Serbian Republic had just been proclaimed in Belgrade. Their leader - Stefan Milutin - wasted no time in declaring a series of wars against surrounding states, quickly re-absorbing the tiny duchies and kingdoms that had broken away from Serbia over the past few years.

This took a scant few months to accomplish, with the nascent republic quickly solidifying its hold on the western Balkans before looking to the south and west. There, the Latin Empire had recently enjoyed a period of revival, attacking and conquering large tracts of Greece and Cherson, only for this swan song to be interrupted by an Armenian invasion from the east.

Eager to both emulate Grim Torgeir and see his young republic expand, Milutin wasted no time at all in declaring war on the Empire, launching a massive invasion of its recently-acquired Greek holdings.

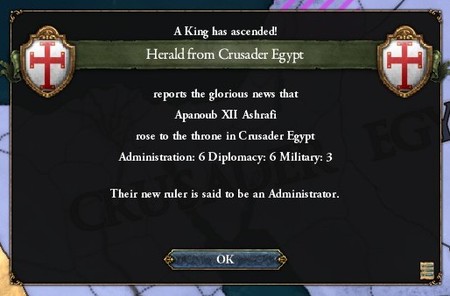

Further south, another monarch ascended the throne of Egypt, ending a decade-long period of regency. Apanoub XII, latest in a long line that stretched back to waning years of the Medieval Era, wasted no time in declaring his intention to crush the Vakhtani Caliphate - once and for all.

The Sahidic king was young, headstrong and overconfident, personally leading his so-called "Army of God" into Anatolia, backed up by the levies of his Sudanese tributaries. At the same time, his ally - Emir Vali XXVI of the Vali Emirate - launched an invasion from the east, marking one of the few times Muslim and Christian worked together in the Middle East.

Needless to say, Emir Vali drew harsh criticism from surrounding powers, with the Khwarezmian Shah threatening to sack and plunder Baghdad for his transgressions.

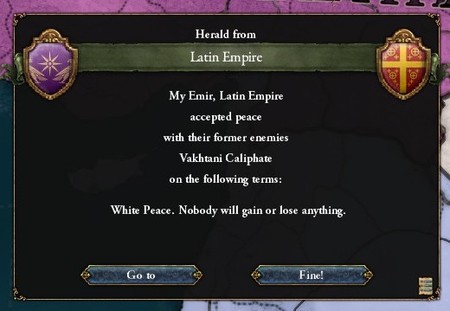

Now forced to face considerable forces to his south, the Vakhtani Caliph quickly made peace with the Latin Empire, settling for status quo despite capturing vast tracts of land in Europe. He withdrew his forces and began the long march towards Adana, where a Crusader army was preparing for siege.

Whilst ancient empires clash in the east, Iberia is suffering through one of its most divided periods in history, with half-a-dozen powers desperately trying to reunify the peninsula as the surrounding behemoths gradually encroach.

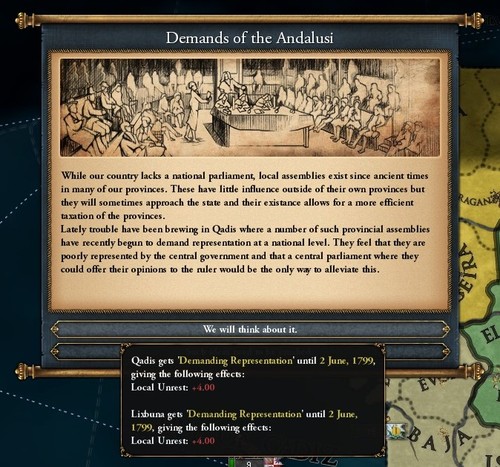

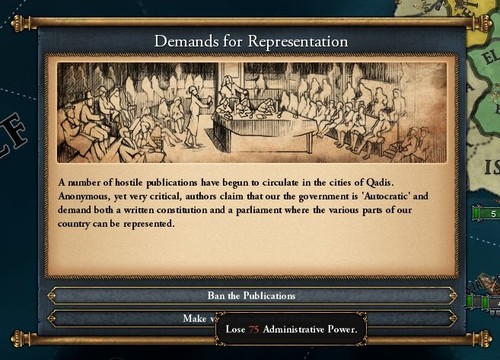

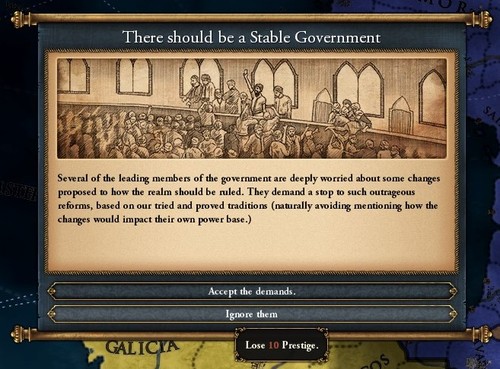

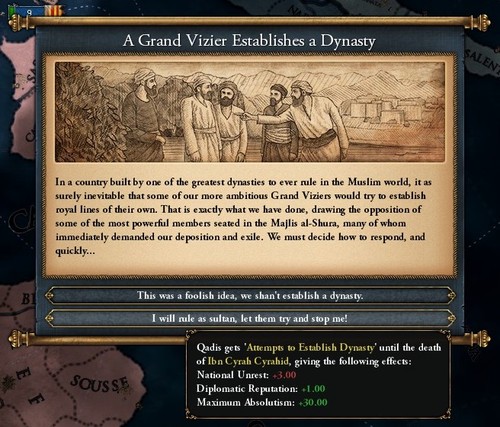

And in Qadis - the largest and richest city in Iberia - Ibn Cyrah is slowly solidifying his hold on power. With his recent reforms in the economy, legislature and military, he has risen to cast a dominating shadow over the entire Majlis, drawing the ire of his many colleagues. When the sheikhs and walis seated on the assembly demanded greater autonomy and representation, however, Ibn Cyrah simply made idle promises and wafted away their concerns.

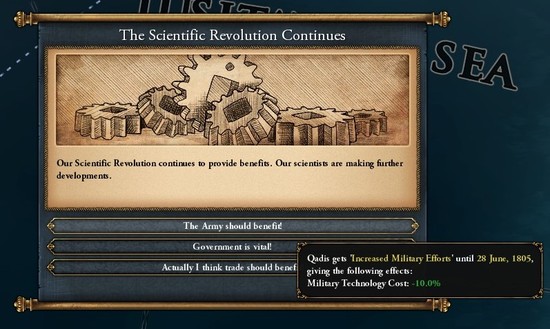

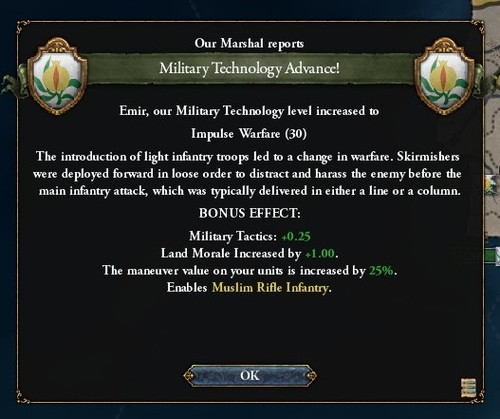

Instead, he directed the focus of Qadis where he desired it - towards the military, his prize and pride. Ibn Cyrah invited countless engineers, marshals and tacticians from Central Europe, where the Revolutionary Wars were rapidly giving rise to new technologies and weaponry, all of which Cyrah was desperate to utilise.

He offered them huge stipends and lavish estates in return for their help in remodelling and developing the Majlisi Guard, which was constantly being drilled in new tactics and strategies. Acting on their advice, Ibn Cyrah further reformed the infantry and cavalry of the army, which had been secondary and inferior to artillery brigades up until then, arming them with rifles and forming specialised contingents of skirmishers and harassers.

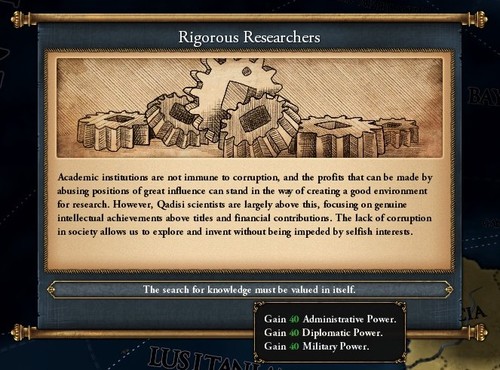

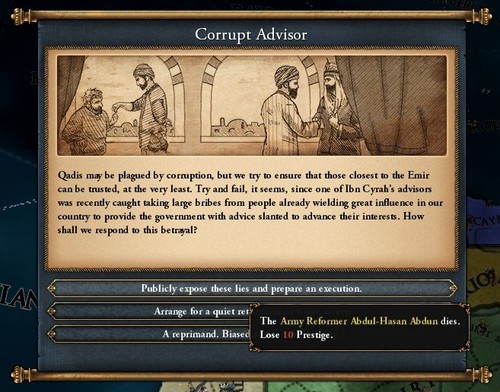

The Grand Vizier also used his authority to slowly chip away at the corrupt institutions of the Majlis. He still couldn’t touch the powerful emirs seated in the assembly, of course, but his recent reforms gave him ever-increasing authority and power, allowing him to purge some of the most corrupt and nepotistic men in the shura (along with one or two of his political opponents).

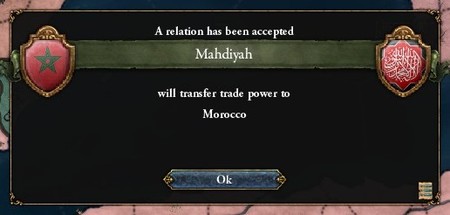

To the north, meanwhile, new trade pacts were being ironed out being the Mahdist Regime and the Almoravid Empire. Majlisi spies picked up on them and, wasting no time at all in making them public knowledge, the assembly declared it proof of the Mahdi’s lies and falsehoods, asserting that he was nothing more than a puppet of the Almoravid Sultan Issam.

There was no doubt about it, the Almoravids would attack sooner or later, it would be foolish to assume otherwise. So Ibn Cyrah began the expansion of the fortifications surrounding Qadis, upgrading the capital’s defenses and making it essentially-impregnable against even the latest artillery. Qadis had to be given priority above all else, after all, if it capitulated then everything the Majlis had worked to achieve would be lost.

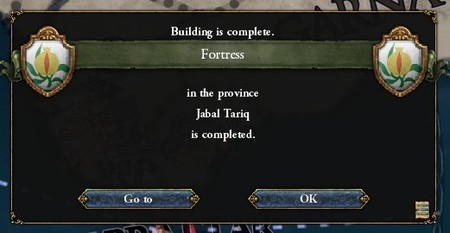

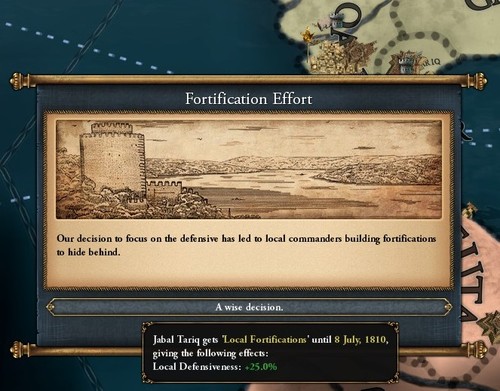

And at the insistence of a particularly loud wali in the Majlis, new fortifications were also set up in Jabal Tariq. The budget was tighter than ever, however, so these fortifications were rudimentary at best, fit only to briefly hinder a Moroccan advance.

Ibn Cyrah also managed to secure additional funds for his personal use, which he immediately invested in the formation of a new fleet, ordering the construction of five threedeckers late in 1788. The Andalusi hadn’t had a proper navy in a very long time, not since the now-defunct League of Merchants were at their height, but the Grand Vizier had dreams of one day wresting control of the Straits back from the Berbers… a lofty ambition, without doubt, but not impossible.

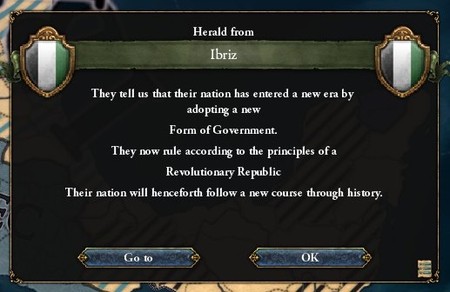

Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, the inevitable finally came about as the Hishami dynasty was overthrown. The peasantry had suffered for centuries as the Hishami governors (and later sultans) extorted and conscripted them in droves, sending them to die in pointless wars in the icy barrens of the north and the swampy wastes of the south.

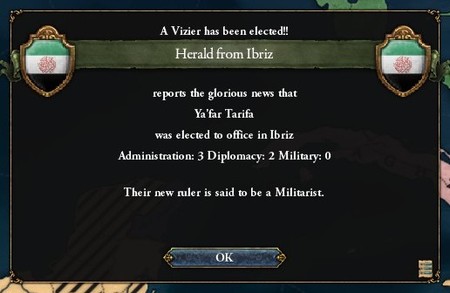

All of this culminated in the toppling of the Hishami, with the Revolutionary Republic of Ibriz proclaimed in the dynasty’s traditional capital, under the guidance and leadership of one Ya’far Tarifa, the general who’d spearheaded the advance of the revolution.

Ya’far immediately ordered the execution of the Hishami Sultan (who’d foolishly surrendered himself to the revolutionaries, refusing to flee his home). And unlike their revolutionary brethren across the ocean, the Andalusi were not so merciful as to use a guillotine… Instead, in a gruesome ceremony lasting hours, the Sultan’s bones were broken one by one whilst he was paraded through the capital, painting a cruel and fearsome picture of the Gharbian revolutionaries.

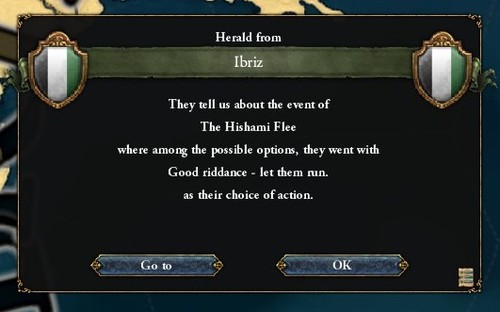

Not all of the Hishami could be captured, however. The Sultan had sent away his immediate family, including his son and heir, mere days before Ya’far and his forces had arrived.

The Hishami escaped across stormy waters to their last safe haven - the island of Yinabii (Jamaica), where they barricaded themselves against the inevitable assassins and invasions. It was there where news of the Sultan’s death first reached his son, Hakim, and it was there where he in turn was proclaimed Sultan of Ibriz and all Andalusi in Gharbia, refusing to surrender his claims to the mainland empire.

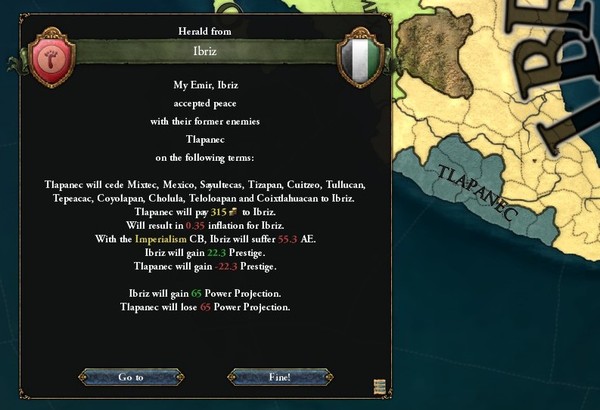

After sending a number of failed expeditionary forces to try and capture the island, Ya’far Tarifa decided to abandon his plans to extinguish the Hishami, instead turning his attention to the west. Under his leadership, Revolutionary forces invaded and occupied large parts of the Tlapanec Empire, only making peace once considerable concessions and harsh tribute were exacted.

The revolution would not be allowed to advance so easily, however. Back in Europe, the elderly and widely-revered King Aton finally passed away, dying with the sure knowledge that later generations would look back to the radiance and light of his rule.

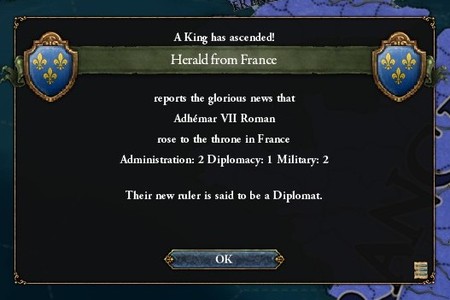

Though he had fathered countless bastards over the course of his reign, however, the Sun King had not sired any legitimate sons. So upon his death, the son of his sister (who was married to a Novgorodian noble) was proclaimed his heir and successor, with Adhémar of the Roman dynasty ascending to become King of France.

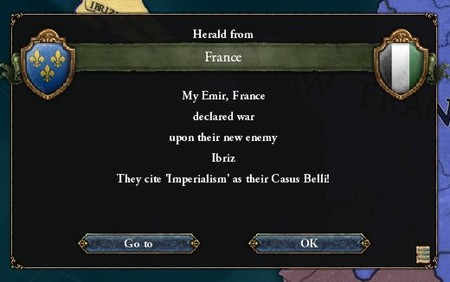

Adhémar would never match the achievements of his predecessor, but despite being a churlish and pompous young man, he was desperate to prove himself a worthy successor. So wasting no time at all, he launched into a war just weeks after his coronation, declaring his intention to squash the Revolution in Gharbia and lay the foundations of a new colonial empire.

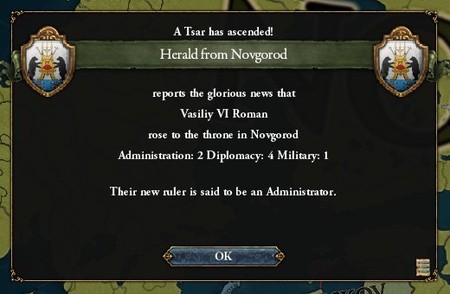

At the same time, his cousin ascended the throne of Novgorod, with Vasiliy VI succeeding his brother after he’d perished due to a virulent flu.

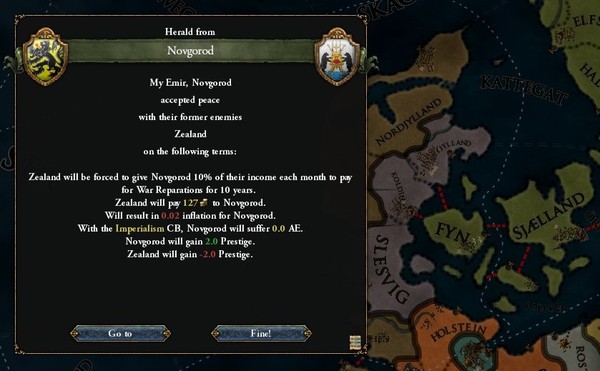

Where his predecessor had been obsessed with forging a trans-continental empire, however, Vasiliy VI was more focused on centralising the vast territories already under his rule. He began by ending the foolish war his brother had begun in Denmark, which had quickly devolved into a guerrilla conflict that’d exhausted the kingdom’s treasury and resources for far too long, making peace on relatively lenient terms.

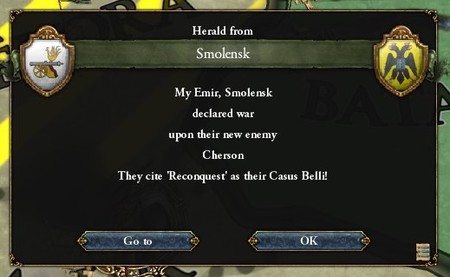

To his west, the Russian kingdom of Smolensk declared war on Cherson - a principality that, over the course of several fortunate inheritances and well-timed wars, had come to rule over large tracts of land in the Caucasus and Balkans.

For Vasiliy, this was a step too far. Novgorod and Smolensk were embroiled in something of a bloodless struggle, as both of the empires were determined to emerge as a single powerful ‘Russian Empire’, a dangerous game that could only be decided through war. And the time for war would eventually come, but not yet.

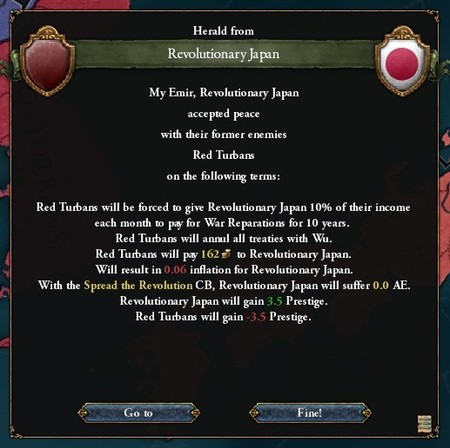

In the far east, meanwhile, another long and gruelling war came to an end. Astonishingly, Japan had failed to establish a foothold on Korea, with the Red Turbans somehow throwing back wave after wave of revolutionary. After four years of devastating war, peace between the two powers was finally reached, with the Red Turbans emerging victorious in all but name.

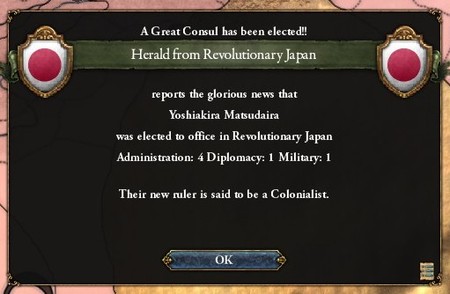

The response to this was in Edo wasn’t great, with another power struggle breaking out amongst the revolutionary council, culminating in a bloody night and the assassination of the Shushō. In his place, another peasant-turned-revolutionary declared himself the grand premier - Yoshiakira Matsudaira.

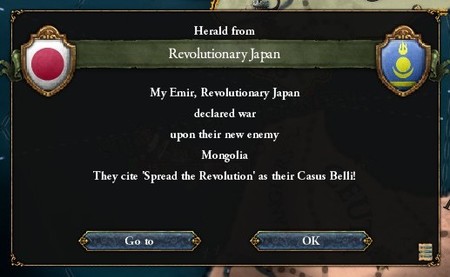

With any more plans to conquer Korea abandoned, the new shushō looked further north instead, where the Japanese already had a tributary state. After meeting with the revolutionary council, Matsudaira decided to start off by conquering the plains of northern Manchuria, and pushing south into China from there.

This wouldn’t be as easy as he’d predicted, however. The many khanates dotting Manchuria were actually vassals to the vast and sweeping Sunni Mongol Empire, which had conducted a wave of successful invasions into China over recent years, and was now drawn against the Revolutionaries in the east.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the Majlis had spent the past few years extensively preparing for an invasion from the south. Slowly but surely, the fortifications in Jabal Tariq were renovated and modernised, now able to repel both land assaults and sea-borne attacks.

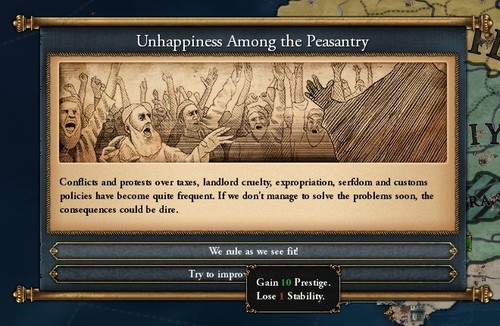

Fortresses were not cheap, however, not by a long shot. And as always, it was the peasantry who bore the brunt of the cost, forced to not only suffer huge tax burdens but also see their children snatched away and conscripted into the Majlisi Guard. In desperate attempts to evade the draft, parents would maim, cripple or blind their own children, refusing to subject them to a life of constant war.

Needless to say, Ibn Cyrah wasn’t very popular amongst the peasants.

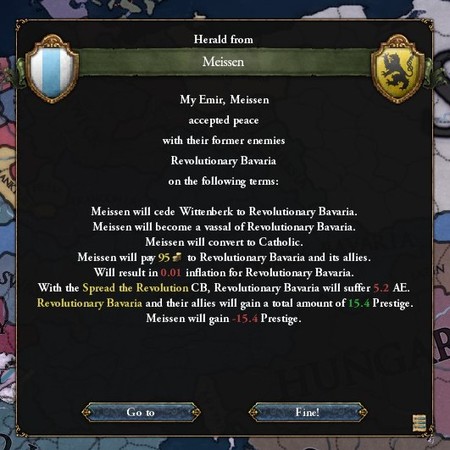

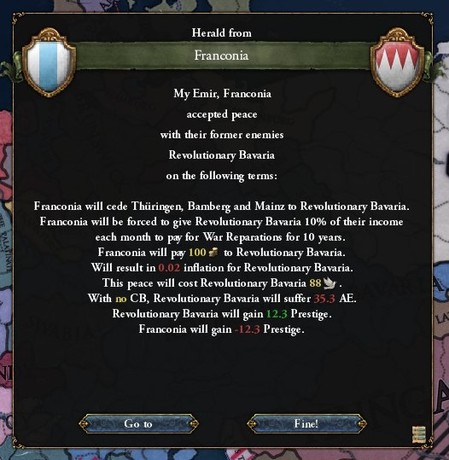

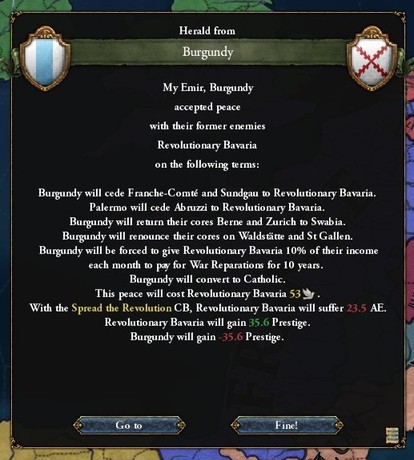

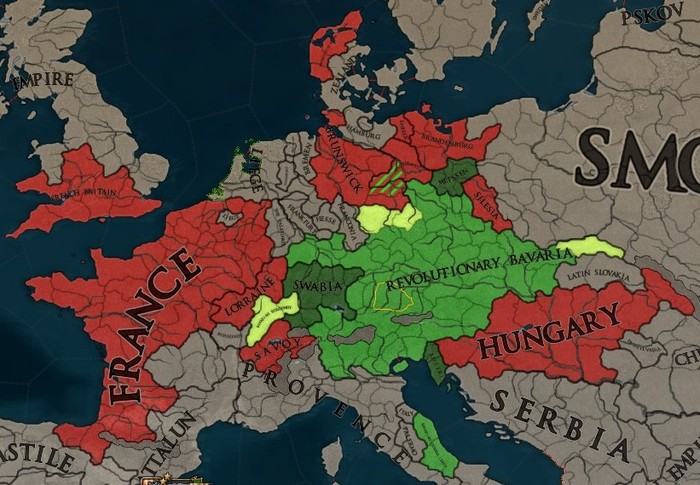

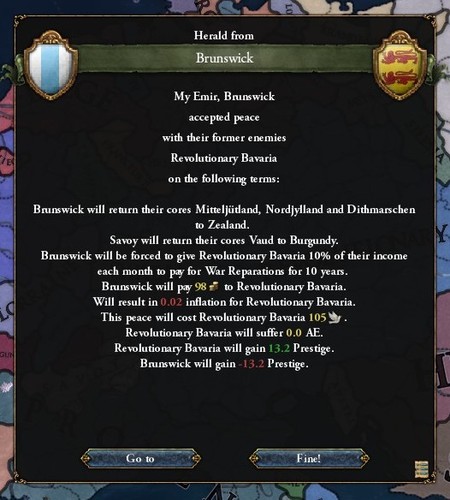

In Central Europe, meanwhile, another series of wars came to an end with the Bavarians emerging triumphant. München descended into anarchy every other day, but on the front lines the Revolutionaries were staunch and undefeated, with countless stories and legends now swirling about Grim Torgeir.

Franconia and Burgundy were both subjected to vassalage, but not before large tracts of their land were annexed to Bavaria. The rapidly-growing republic now swept across the southern half of what had once been the Holy Roman Empire, something that had been inconceivable just two decades past, and it wouldn’t end there. Grim Torgeir wouldn’t stop until his ambitions had been realised, and a united Germany ruled Europe with an iron fist.

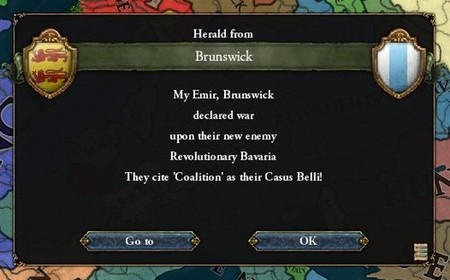

The rest of Europe wouldn’t just roll over for him, however. Led by the Duke of Brunswick, the First Coalition formed in opposition to the aggressive Bavarian Republic and its radical ideals.

Backed by the powerful Kingdom of France and an array of small but rich German principalities, the forces of monarchy were finally prepared to face the revolutionaries in open battle, with clashes erupting all along Bavaria’s borders. With the Germans in the north, France in the west and Hungary in the south, Grim Torgeir had his work cut out for him.

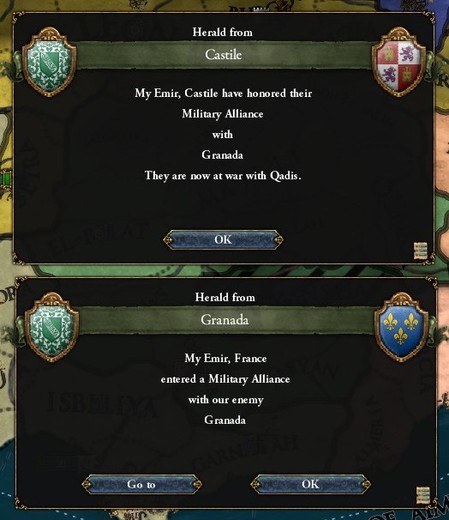

For the powers of Central Europe, this was the war that would surely decide between their survival or destruction, but for others it was simply an opportunity to expand. With the Almoravids unusually quiet and the French distracted by the revolutionaries, Grand Vizier Ibn Cyrah finally felt secure enough to launch a new war, declaring on the Jizrunids once again.

Castille, who’d formed an alliance with the Jizrunid remnants, quickly pledged their support for the enemy. More worryingly, however, Andalusi spies reported that they had also sent envoys to Paris… and those same envoys returned with word of alliance.

Still, King Adhémar would surely want to focus his resources on combating the Revolution? Some tiny Iberian struggle couldn’t be that important to him.

Unfortunately for Ibn Cyrah and the Majlis, however, that wasn’t the case. Mere days after the war had been declared, the King of France also announced his support for the Jizrunids, vowing to send a force large enough to reduce Qadis to rubble before year’s end.

Needless to say, things hadn’t gone exactly to plan.

Regret was no use, the only thing that Ibn Cyrah could do was act, and act quickly. Determined to land the first blow, he marched the Majlisi Guard westward, where a large Castilian force had invaded and besieged Lishbuna. The Jizrunid forces also arrived from the east, so Ibn Cyrah manoeuvred the Guard and managed to pin them down, hoping to annihilate the smaller army first.

It wouldn’t be so easy, however, with the Castilians rushing south on a forced march and joining the fray before long. The massive battle of Baja raged for six uninterrupted days, and despite taking heavy losses, the superior discipline and professionalism of the Majlisi Guard saw them emerge victorious.

Whilst battle was met in the south, however, Andalusi scouts caught sight of a large French force on the march. Stopping only to crush overenthusiastic rebels, the huge army crossed the border and pushed into Majlisi territory deep in the winter of 1792.

With the French army said to number almost 70,000 proven soldiers, Ibn Cyrah wasted no time in pulling his forces back to Qadis, where he recruited an additional 15,000 mercenaries to augment the Guard. Facing crises at home and on the field, however, the Grand Vizier was forced to leave the army in the hands of his junior - a talented commander by the name of Ibn Timu.

Ibn Timu's immediate advice was to fall back to more favourable terrain. So the Majlisi Guard retreated to Granada, where the mountainous country would play to their strengths, and began making preparations for battle. Confusingly, however, the French Army turned around and marched in the opposite direction even before they reached Granada, leaving Majlisi generals bewildered.

Convinced that the French had been recalled because of a reversal or upset in the Revolutionary War, Ibn Cyrah decided to push onto the offensive once again, attacking and once more pinning down a small Castilian force in Baja.

Unfortunately for the Grand Vizier, however, the French withdrawal had been nothing more than a ruse to lure the Andalusi away from Granada. The moment battle broke out, another 55,000 Frenchmen thundered seemingly out of nowhere, probably having been hidden by the Mahdi, who only benefited from the defeat of the Majlis.

All the same, Ibn Timu managed to quickly crush the Castilian force and spin around in time to face the French army, desperately trying to organise a sturdy defense to counter their numbers...

The Majlisi Guard proved their worth in the battle that followed, matching the French man-for-man, doggedly refusing to give up an inch of ground, following their commander's orders to the word, and furiously fighting to their last breath. For the first day of heavy fighting, the battle could have gone either way, with the Guard’s discipline equalled by French numbers.

But then reinforcements poured onto the field, with Castilians arriving from the north and more Frenchmen from the east. The plains of Baja were wide and empty, perfect for deploying long lines of soldiers, and terrible for organising any sort of defense against it.

So after holding out for another half-day, Ibn Timu was forced to call for a retreat, taking heavy losses as he led the Guard back to Qadis.

Grand Vizier Ibn Cyrah, in a rare act of humility, took full responsibility for the loss. He placed supreme command of the Guard in the hands of Ibn Timu and returned to Qadis, where another crisis had broken out in the Majlis al-Shura.

Fortunately for the Majlis, the French retreated from Qadisi territories after the battle, perhaps convinced that one defeat was enough to crush the spirit of the Andalusi.

Ibn Cyrah would not surrender so easily, however. He was nearing eighty years of age and would undoubtedly be calling on death’s door before long, and he would do so with his head held high, riding on the wave of one last victory.

So the Grand Vizier took out massive loans from the Andalusi Bank, with all this money funnelled into rebuilding the army. The core of the army was still made up of the disciplined, well-drilled soldiers of the Majlisi Guard, but they were now surrounded by a swarm of green recruits, teenagers and farmboys who’d been given uniforms and little else.

Before long, the Guard was brought back up to a respectable strength of 40,000 soldiers, all under the command of Ibn Timu. The young general set off on a new campaign in the spring of 1794, recapturing countless castles and driving back the small Castilian forces with remarkable ferocity, before pushing into Castille proper.

A tad aggressive, maybe, but he had to be. This was his opportunity to prove himself, and he would not be denied.

In the Near East, meanwhile, the Egyptian-Armenian war came to an end with another loss for the latter. Now largely confined to Anatolia, also called Greater Armenia, this defeat only further solidified the rapid decline of the Vakhtani Caliphate, which had once ranged from the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medine in the south to the Caucasus in the north.

And unless their fortunes were revived, and soon, this may well herald the fall of Armenian influence in the Near East altogether.

In the far west, meanwhile, the Ibrizi Revolutionaries managed to secure the surrender of King Adhémar and the French, who were forced to concede defeat after suffering a series of losses against Bavaria. Now free from conflict in the new world, France could focus its full resources on wars in the old, sending greater numbers against Bavaria in the east and Qadis in the south.

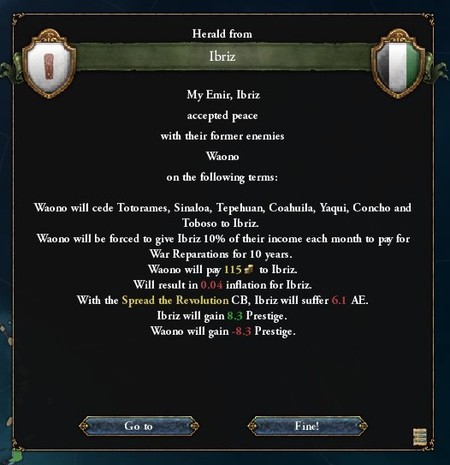

For the Ibrizi, however, this only reaffirmed their own position and influence in Gharbia, where lack of competitors meant that they were sure to emerge as the dominating state in the west. Determined to send a clear message throughout the continent, Ya’far Tahir went on to declare on the Polynesian kingdom of Waono, looking to expand his borders and establish puppet states.

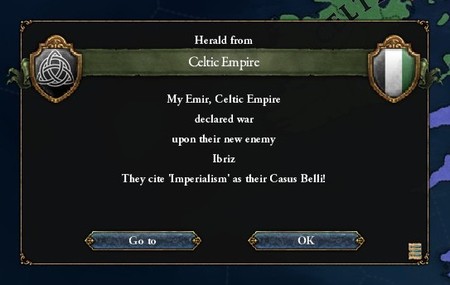

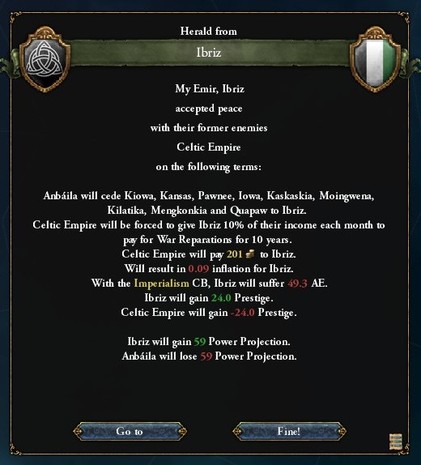

Again, however, he would not be allowed to do it so easily. The Celtic Empire ruled over vast tracts of northern Gharbia, so the Revolution threatened them more than any other colonial empire, and they were fast becoming desperate to halt its advance.

So deep into 1795, the High King established a temporary alliance with the Waono and formally declared war on the Ibrizi Republic, looking to re-install his former rivals in the Hishami as the Sultans of all Ibriz.

Moving back to Iberia, however, 1796 heralded the outbreak of a huge scandal. Ibn Cyrah had just turned eighty years of age, and in the middle of the traditional city-wide celebrations and festivities, the Grand Vizier called a sudden meeting of the Majlis to make a special announcement.

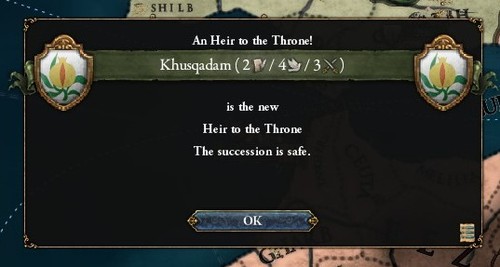

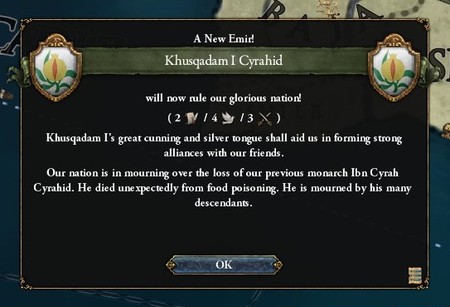

There, before all the emirs and sheikhs and walis of the assembly, he declared that his eldest son - Khusqadam, at just 15 years of age - would be his heir apparent, to succeed him and the Majlis upon his death. Ibn Cyrah, it would seem, wanted to establish a dynasty of his own.

Obviously, huge protests immediately broke out, with many nobles of the Majlis refusing to recognise Khusqadam, claiming that Ibn Cyrah had gone senile, and even going so far as to demand his immediate arrest and deposition. In their defense, this went against everything the Majlis had fought, bled and died for as they struggled to overthrow the Jizrunids…

Ibn Cyrah may have been very old, but it was also clear that he had been planning this for a very long time, with his guard quickly isolating and jailing the loudest of these protestors. After that, things quickly quieted down, and Khusqadam began accepting pledges of fealty.

On the war front, meanwhile, the Emir of Qattalun finally ended his feuds in the north and agreed to aid the Majlis in its war. Rather than join up with the Majlisi Guard, as Ibn Timu requested, he sent his 25,000-strong force to directly besiege Medina Laqant, hoping to capture the Jizrunid sultan and end this farce once and for all.

And predictably, the French quickly descended on him there, engaging and wiping out the Catalan army over the course of three bloody hours.

The Emir’s navy, however, still came in very useful. Boasting an impressive 55 ships, most of which were galleys, the Qattalun Fleet kept Iberian coasts free of both Castilian and Jizrunid ships, with the French Navy tied down in the North Sea.

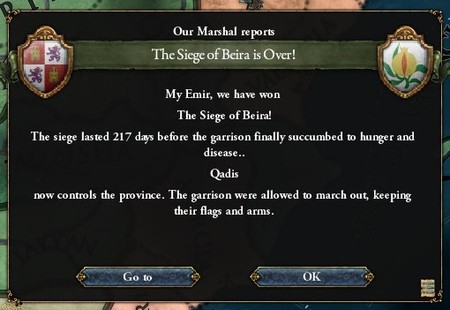

Ibn Timu, on the other hand, had spent months orchestrating a successful siege. He had Beira, Castille’s largest and strongest fortress, surrounded for more than seven months without break, launching regular assaults and skirmishes, before the garrison finally capitulated and surrendered.

Once he’d seized nearby forts and cities and installed garrisons of his own, Ibn Timu led the Guard eastward, with the march culminating in another siege. His guns now blasting at the walls of Burgos, the marshal knew full well that if he could capture the Castilian capital, the war was as good as won.

In the south, meanwhile, the Mahdi had gathered his most trusted imams in a solemn ceremony. Proclaiming the dawn of a renewed era of jihad, he declared war on the decadent Jizrunids in the east, vowing to see the stain that was their dynasty wiped off the face of the earth.

And of course, now that it was the Mahdi and not the Majlis going on a warpath, nobody was willing to defend the Jizrunids. Typical.

In the east, the war between Smolensk and Cherson came to an end, with the Russians annexing almost the entirety of Cherson’s holdings north of the Caucasus Mountains.

Further west, meanwhile, Majlisi allies sent word that the Revolutionary forces were slowly being pushed back, though the kingdom of Hungary had put up scarcely any resistance before folding.

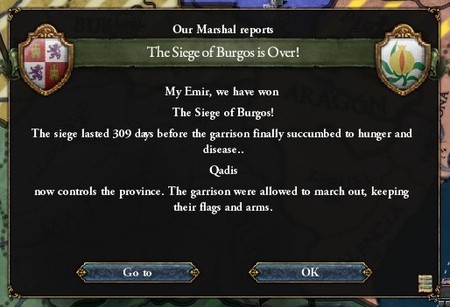

This news was quickly sent to Ibn Timu, who began intensifying assaults on Burgos, desperate to breach its walls before the French could send a relief army. Equally desperate to stall for the French, the Prince of Castille threw every man he had at the Majlisi Guard, forcing Ibn Timu to divide his army into two - to both repel the Castilians and assault Burgos at the same time.

The inevitable could not be avoided forever, however, and another French army numbering 70,000 crossed the Pyrenees late in 1797.

Majlisi scouts were quick to report the advance of the French relief force, but Ibn Timu only doubled and tripled his attempts to breach Burgos, throwing literally the entirety of his force at the walls of the city. If the French caught them below these same walls, then everything was lost, but if the city could somehow be captured…

Then he would have leverage.

Burgos fell mere hours before the French arrived, and it didn’t even come down to the walls being breached. Instead, all it took was a single Castilian soldier opening a gate to a small contingent of the Majlisi Guard, not knowing relief was nearby and futilely hoping that he’d be spared in the inevitable sacking.

The Majlisi Guard flooded into the city, and though the French still pinned down a good portion of the force and utterly annihilated it, Ibn Timu managed to capture Burgos. That was all that mattered, that meant all of Castille was now under his control, and that meant he’d won.

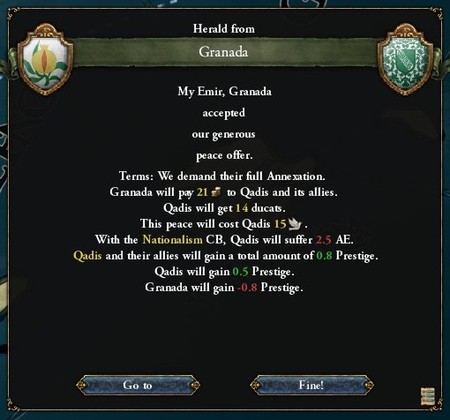

Over the course of the next few days, Ibn Timu negotiated with the prince of Castille on behalf of the Majlis, forcing him to concede all of his Portuguese holdings to Qadis - which included some of the richest and most lucrative cities in all Iberia.

At the same time, Mahdist forces had managed to capture Medina Laqant, annexing the city to their burgeoning realm. A large number of Iberian Jizrunids were also captured - including the grandsons of the Mad Hunchback - and were quickly transported overland to Qurtubah, where the Mahdi made an example by subjecting them to public humiliation and execution by wheel.

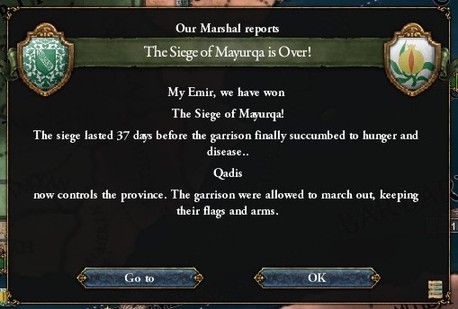

This wasn’t great news for the Majlis - but it did give Ibn Timu the opportunity to embark from Ishbiliya with a small expeditionary force, crossing through the straits and storming the beaches of Mayurqa, where the last remnants of Jizrunid rule persisted.

The islands were annexed to the Majlis, and with that, almost 750 years of Jizrunid rule in Iberia is finally and irrevocably brought to an end. A branch of the Jizrunids still rule in Palermo, a few distant cousins contro scattered castles and cities in Iberia, but the chances of a restoration are now all but impossible, with nobles, ulema and merchants throughout the peninsula all devoted to causes of their own.

Now, the battle for Iberia truly begins, with the Majlis and the Mahdiyah taking their place as opposing players in a dangerous game, a game that will determine the future of the peninsula.

The death count of the Last Majlisi-Jizrunid War.

And it is the Mahdi who makes the first move, declaring war on the princedom of Castille, looking to annex the mountainous provinces it still clings to whilst the Majlis are bound by truce against intervening. Tens of thousands of Sunni fanatics thus pour into the mountains of Asturias as a new century dawns, hoisting the banners of the Mahdi skyward, chanting battle verses from the Quran and looking to finally extinguish what little is left of Christendom in Iberia.

As the two remaining taifas of Iberia prepare to clash, the daughter state of Al Andalus rears proudly in the west, emerging from yet more successful wars against Waono and the Celtic Empire. Large tracts of north Gharbia remain scarcely populated, but revolutionary forces managed to seize key forts inland and cities dotting the coast, not to mention utterly destroying any Celtic attempts to recapture them.

Once the countless rounds of negotiations were over and done with, peace was declared and work on redrawing Gharbian maps began, with the Ibrizi Republic now an immense empire that stretched from Panama in the south to the Great Plains in the north, along with everything in between.

The Hishami Sultan may still redden in the face and clench his fists, but for all intents and purposes, this is the dawn of a new era for Ibriz. All of Gharbia stands open for Ya’far Tahir and his revolutionaries, with the only question being where to strike next.

Back in Europe, meanwhile, Grim Torgeir managed to orchestrate a remarkable counterattack that saw the monarchist cause reverse in a matter of weeks. Utilising mass mobilisation in ways that have never been attempted before, the revolutionaries were at the gates of Braunschweig before Christmas of 1799…

And with that, the War of the First Coalition comes to an end. Unfortunately for all of Europe, however, it would not be the last of the revolutionary wars. Not by a long shot.

In the Balkans, the Serbian Republic had also seized victory on the battlefield, capturing Macedonia and large tracts of Greece from the Latin Empire. The Serbs aren’t likely to stop there, however, with their eyes set on uniting all of the Balkans in a grand republic.

Moving back to Qadis, however, the last days of 1799 are heralded by the death of Ibn Cyrah. The Grand Vizier had been approaching ninety years of age and was surely about to drop any day then, but Ibn Cyrah was actually poisoned, no doubt by members of the Majlis refusing to recognise his son as his successor. Indeed, Cyrah had actually been preoccupied with ensuring a smooth transition of power when he died, buying off those who could be bought and killing off everyone else.

All the same, however, Ibn Cyrah will likely be remembered for centuries to come. He came from nothing, climbed the rungs of power through sheer ingenuity, and emerged to become one of the most powerful men in the history of al-Andalus. His remarkable life is blemished by his ruthless powermongering and occasional cruelty, but it was him who stabilised the Majlis where it was chaotic and anarchic, it was him who laid the foundations of a new national army, and it was him who began down the long road of reunifying al-Andalus.

One of Ibn Cyrah’s greatest ambitions, however, was to establish a dynasty of his own. He had grown up a firm believer in the ideals of the Majlis, but the sheer corruption of the assembly left him a jaded shell of the man he once was, convinced that the only way to establish a stable nation-state was to have a monarch leading it.

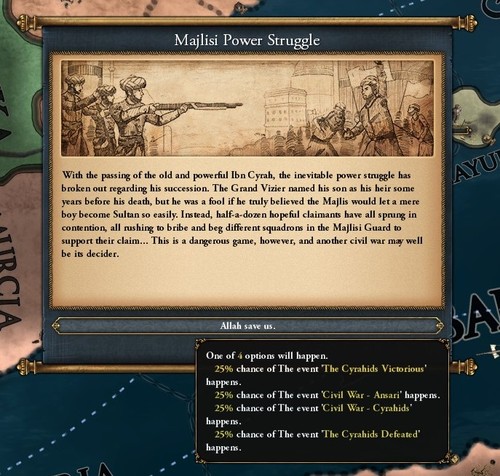

The Majlis would not give in so easily, however. Once Ibn Cyrah’s closest allies, Abi Rod and Sheikh Farih masterminded the assassination of the Grand Vizier, and even before his death was announced they’d begun making deals with the captains of the Majlisi Guard, offering them huge salaries and estates in return for their support during the oncoming power struggle.

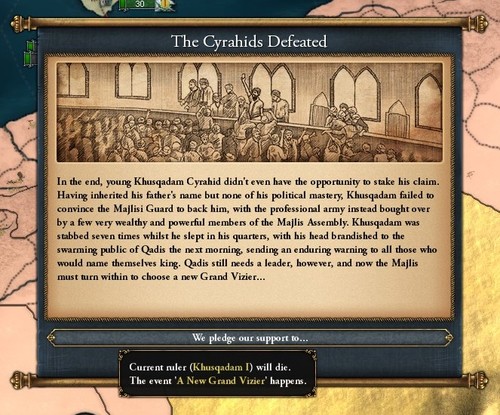

Khusqadam - the son and chosen successor of Ibn Cyrah - did exactly the same, but he had nothing on the politicians of the Majlis, who were well-versed it what it took to eliminate an opponent. Before the youngster knew what had happened, an elite order within the Majlisi Guard had stormed his palace, stabbed his children and forced him to his knees. Within an hour, it was all over.

The Cyrahids would never rule as Sultans, and to show the world what happened to those who would name themselves king, the Majlis had Khusqadam’s head paraded through Qadis for three days and three nights. When it was finally thrown to the hounds, the head was unrecognisable, tongueless and bald with hollowed eyes and rotting flesh.

Still, the question remains - who is to rule Qadis? Abu Rod, Farih, or some other member of the Majlis? Would the Jizrunids of Palermo attempt to intercede? Or would another, less obvious candidate rise to triumph against the old and the corrupt?

The decision will come down to the Majlis, but the world is quickly changing as the ideals of the Revolution begin to encroach into Iberia, and a decision will have to be reached quickly. The forces of radicalism rest for no man, and unless a unifying figure rises to unite the Majlis al-Shura, Qadis may well disintegrate into infighting and irrelevance.

World political map:

World religious map: