Part 62: The Calm Before the Storm

sorry, this is another long one.Chapter 30 - The Calm Before the Storm - 1799 to 1810

The nineteenth century opens with the death of Ibn Cyrah, having ruled as Grand Vizier in Qadis for almost twenty-five years before meeting his demise, poisoned by some of his closest allies after attempting to establish a dynasty. Two of his assassins - Sheikh Al Farih and Wali Abi Rod - immediately turned on each other as they scrambled to name themselves his successor, but unbeknownst to them, another figure emerged to stake his own claim.

Ibn Timu, hand-picked by the former Grand Vizier to become commander of the Majlisi Guard, declared in a heated speech that both Al-Farih and Abi Rod were criminals and traitors, fit only for execution. And to the horror of the two elderly politicians, factions in the Majlis actually began flocking to support Ibn Timu, tired of the corrupt regime they headed.

With his campaign snowballing, Ibn Timu managed to obtain a Majlisi mandate to hunt down the assassins, quickly dispatching soldiers to apprehend Al-Farih in Algeciras. The old nobleman predictably refused to surrender himself, however, with the confrontation quickly escalating into a brawl. A few hours later, the Farihian estate was littered with bodies, with the sheikh himself killed in the midst of the commotion.

Hearing of his accomplice’s death and thinking the worst, Abi Rod boarded the first ship leaving for Safi with his family and little else, escaping Majlisi authorities by mere hours. Ibn Timu didn’t care much whether his enemies were dead or exiled, however, so long as they were out of his way. And with no one left to challenge his claim, the commander finally declared himself Grand Vizier of Qadis, with the Majlis having little choice but to accept him.

Ibn Timu, for all his accomplishments on the battlefield, had very little experience in politics - but the young soldier was very quick to showcase his potential. Within days of proclaiming himself Grand Vizier, he’d managed to win over a good deal of the Majlis, charming foes where he could and simply making concessions where he couldn’t.

Timu’s ambitions weren’t limited to simply making pleasantries, however. Qadis at the turn of the century was not in a good place, geopolitically. To the south, the Almoravid Empire stood stronger than ever, gradually expanding its influence all across the Mediterranean. To the north, meanwhile, the Mahdist Regime was aggressively expanding in every direction, backed by the Moroccans. Still, Ibn Timu shared his predecessor’s ambitions to revive al-Andalus, determined to unite the entire peninsula under his rule.

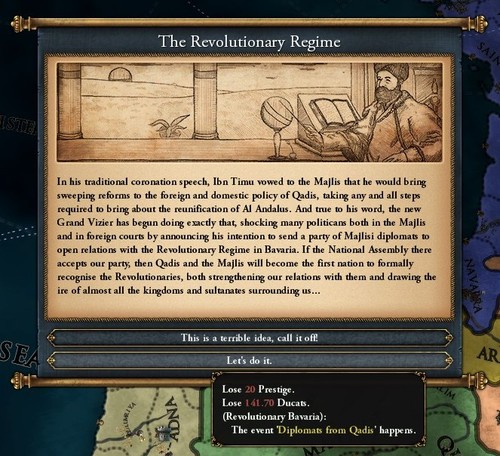

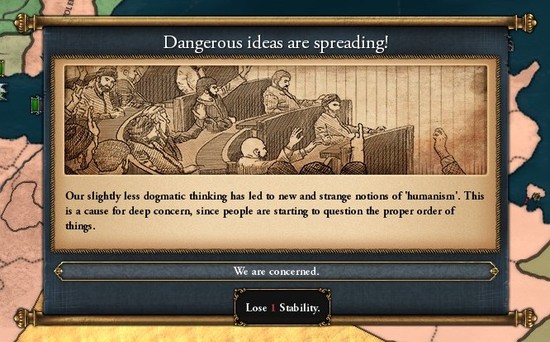

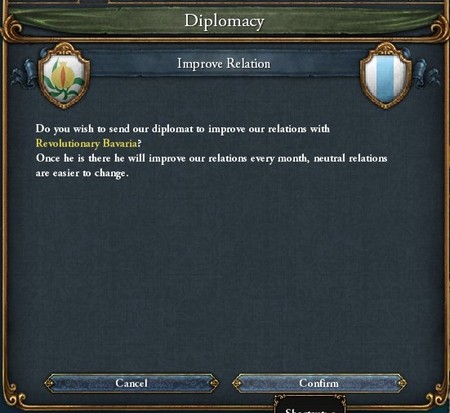

No easy task, needless to say, Ibn Cyrah had tried and failed to accomplish just that. Ibn Timu had learned from his mentor’s failures, however, and he knew that the time had come to try something new. Thus, within weeks of ascending the throne, the new Grand Vizier dispatched a large embassy to München - where they would formally recognise the Revolutionary Regime of Bavaria, and begin cultivating relations with the republic.

Knowing that the reaction wouldn’t be favourable, Ibn Timu operated under secrecy for as long as possible. Once the embassy left Qadis, however, the rumours were confirmed and a crisis erupted in the Majlis, with large chunks of the assembly denouncing and criticising Ibn Timu.

In München, fortunately, the National Assembly were all too happy to accept the Andalusi embassy. Majlisi diplomats met with leading members of the Revolutionary Regime, including the famous Grim Torgeir, and negotiations to reach an alliance between the two powers began soon after.

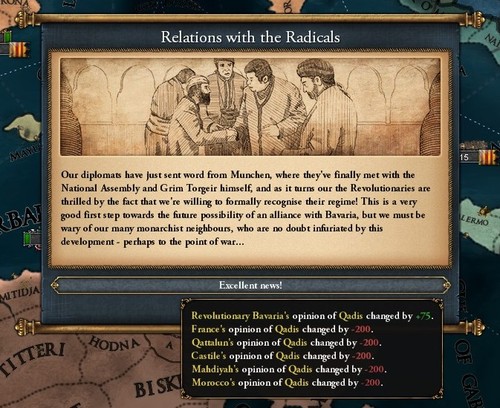

And with that, Qadis became the first nation to formally recognise the Revolutionary Republic. Uproar was quick to break out in response to the move, however, and this anger was not limited to within the Majlis, with near every neighbouring king or sultan taking the time to condemn and lambast Ibn Timu’s decision.

Still, the Grand Vizier refused to retract or recall the embassy, and with the Majlisi Guard under his thumb, any opposition within Qadis was quick to melt away.

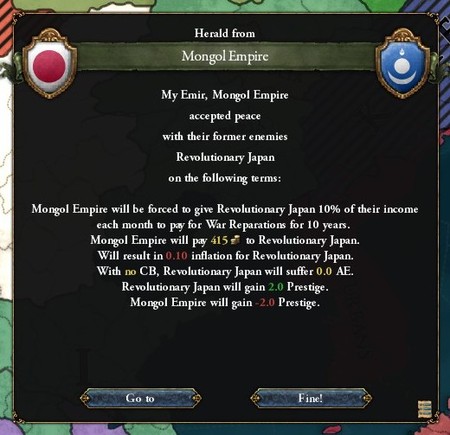

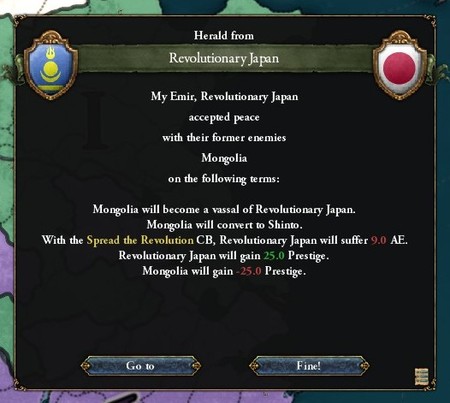

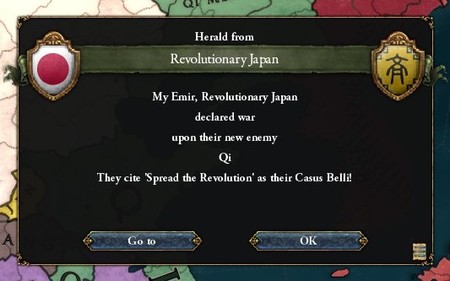

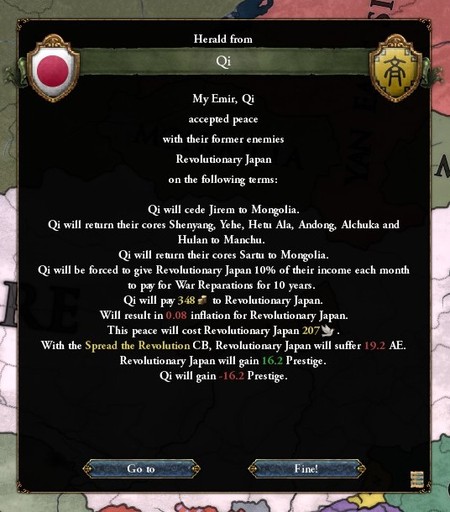

In the Far East, meanwhile, the Republic of Japan finally began scoring some much-needed victories. Adopting the tactics used by their mainland puppets, the Revolutionary Army managed to defeat the forces of the Great Khan in a series of battles, with the war only ending when the khan agreed to surrender his possessions in Manchuria.

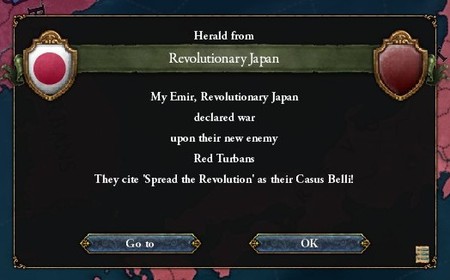

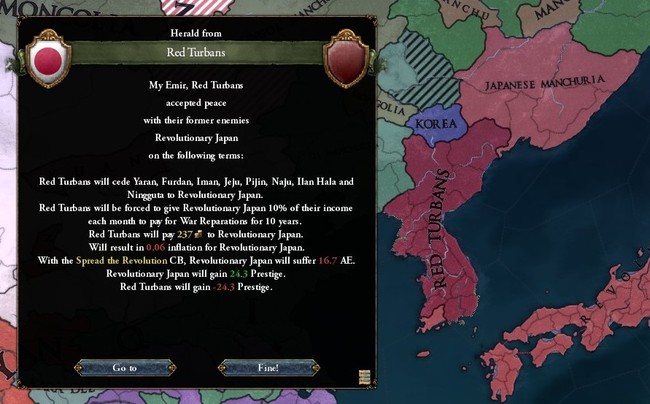

With more experience under their belts, the Japanese turned their sights back to the Korean peninsula, where the Red Turban Regime was waging war on Joseon holdouts in the northern mountains. After long months of preparation, the Revolutionaries launched a second invasion of the peninsula, with thousands of Japanese flooding across the border in the north and simultaneously disembarking onto the southern coast.

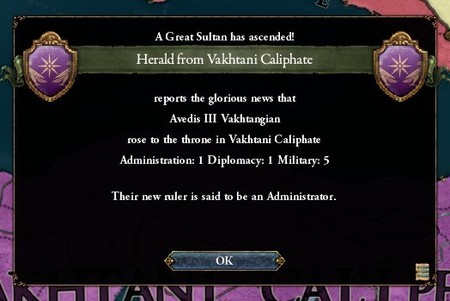

In the Near East, on the other hand, a new Sultan ascended to the Vakhtani Empire. Despite still calling themselves "Sultan of Sultans" and "Caliph of All Muslims", the Vakhtani dynasty was in steep decline, having suffered a series of disastrous defeats both in the Middle East and in Europe.

The young and ambitious Sultan Avedis III, however, was determined to stymie this decline and reverse the fortunes of his empire. Within weeks of his coronation, the Sultan left his capital to take charge of an army, intent on earning a name for himself.

And it took a scant few months for Avedis to prove himself on the battlefield, reversing an invasion from the west and seizing large parts of the Latin Empire. The war ended with the Vakhtani Caliphate expanding in Europe for the first time in centuries, annexing Thrace and parts of Latin Greece in the ensuing peace treaty.

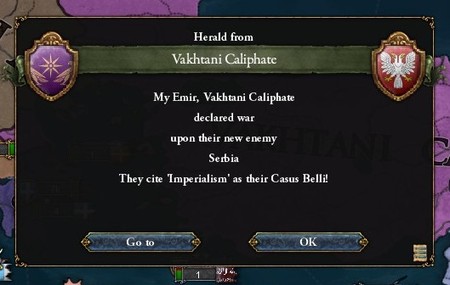

Sultan Avedis wasn’t going to stop there, however. He knew that expansion into the Balkans was the future of his empire, so after a few months of recovery, he declared an invasion of his own.

And as battles broke out all along the Armenian-Serbian border, the panicked revolutionary council in Belgrade descended into chaos over how to respond, with the power struggle only ending when a general named Željko Dragutin seized control of the city. Executing his rivals and declaring himself dictator, Dragutin refused to treat with the Muslims, marching a large army to meet them on the battlefield instead.

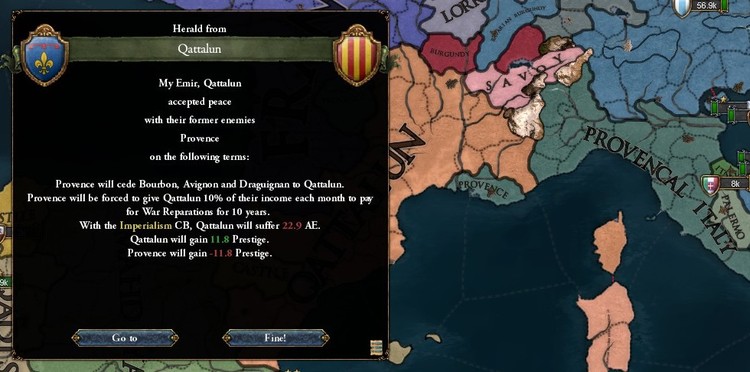

To the south of France, meanwhile, another border conflict between the Emirate of Qattalun and Kingdom of Provence had escalated into full-blown war. This came as no surprise to anyone, with Emir Abdul-Rahman pouncing on any and every opportunity to war with his Occitan neighbour, dreaming of a Mediterranean empire that would stretch from Valencia to Pisa.

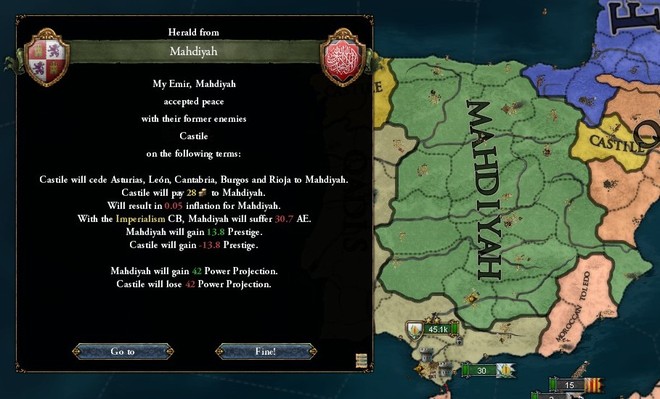

Back in Iberia proper, the forces of the Mahdi had managed to push across Castille with very little resistance, terrorising the countryside without mercy. And late in 1801, a year-long siege ended with the Mahdist army breaching the sturdy walls of Burgos, pouring into the Castilian capital and seizing the citadel. As though that weren’t enough, the city was also subjected to a brutal sacking, with the Christian population looted, raped, murdered and massacred over the course of four bloody days.

The prince of Castille had fled Burgos weeks earlier, of course, but the sacking of his capital finally forced him to the negotiating table. And fortune was not in his favour, with the Mahdi demanding nothing less than the cessation of almost all his territories, save for a few cities dotting Galicia and western Aragon.

With the treaty quickly finalised and signed, the Mahdiyah now swept from Qurtubah in the south to Asturias in the north, a power in its own right. For obvious reasons, the Mahdi’s recent conquests greatly worried the Majlis, who quickly authorised Ibn Timu’s request to expand the standing army to almost 50,000 soldiers.

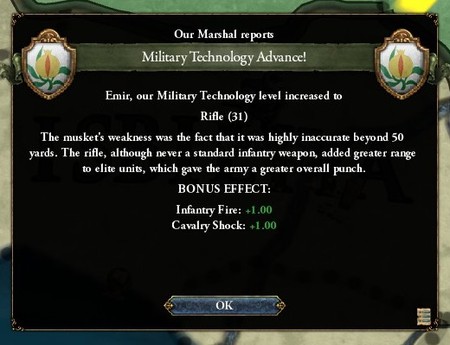

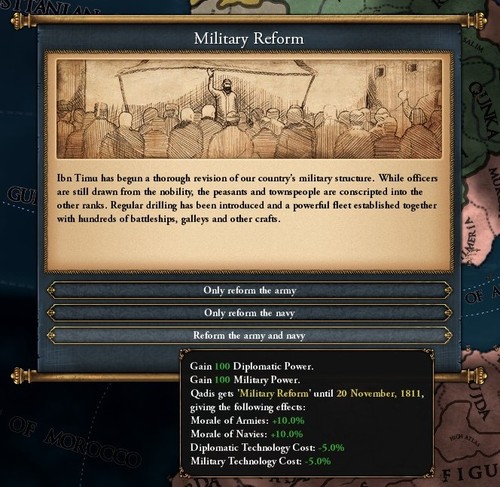

And with the aid of Bavarian engineers, Timu also continued with the military reforms that Ibn Cyrah had begun, supplying the Majlisi Guard with the latest weaponry developed during the Revolutionary Wars. By the end of 1803, new regiments were formed armed with the experimental rifle, far more accurate and devastating than the muskets that had been used up until then.

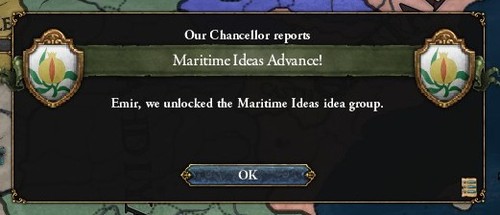

Once more sharing the vision of his predecessor, the Grand Vizier also worked on slowly expanding the navy of the Majlis. It was a measly force when compared with the massive Almoravid Fleet, sitting at just eight threedeckers, but that was still enough to turn Qadis into a regional power on the seas.

And it would only improve from there, with Ibn Timu placing an order for five more heavy ships later next year. The Grand Vizier also invited naval tacticians from Bavaria to help train his sailors, hoping to instil a maritime tradition into the youth of Qadis.

The Majlis had complete suzerainty only over southern Andalusia and Portugal, however, which meant that their manpower pool was limited to those areas. Thus, in an attempt to encourage migration and population growth, Ibn Timu also implemented far-reaching agricultural reforms that saw production in the western marches skyrocket.

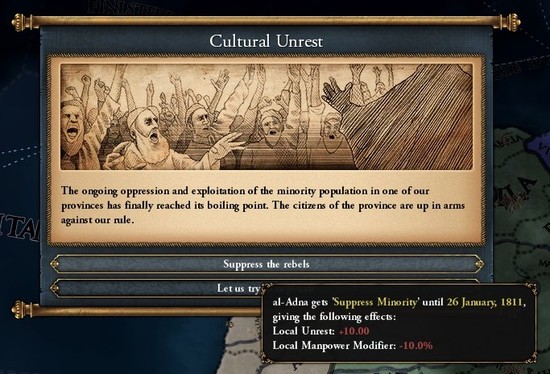

The only way to both implement these reforms and maintain a steady income, however, was through harsh taxation of the suffering population - especially those subjected to the Jizya tax. Unsurprisingly, this led to tensions in the western provinces rapidly climbing, with the local Portuguese tired of decades of exploitation and mistreatment.

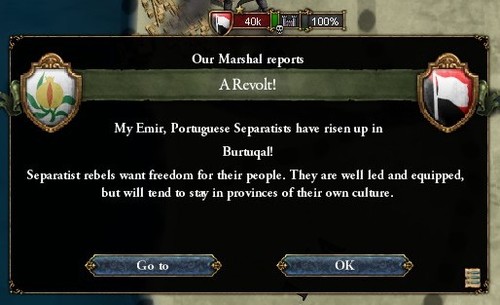

Ibn Timu took a harsh stance against any unrest or dissidence, sending in regiments of the Majlisi Guard whenever tax figures began dropping. This only worsened the tensions, which finally erupted into open rebellion early in 1805, with the Portuguese population of Burtuqal rioting and seizing control of the city, lynching the governor appointed by the Majlis as they did so.

Leading the army into Burtuqal, Ibn Timu crushed the revolt after a short but bloody battle, chiefly consisting of thick fighting in the streets and alleyways of the city. The Grand Vizier then had the instigators of the rebellion hung from their necks as punishment, leaving their bodies to rot for weeks afterward as a warning to future rebels.

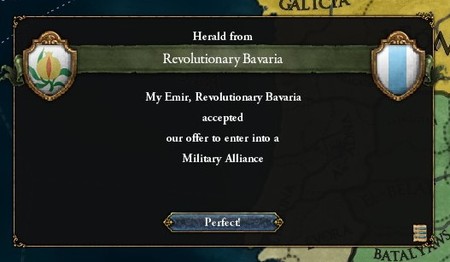

Once back in Qadis, Ibn Timu continued improving relations with the Germans. Whilst his embassy was still hammering out the details of a pact binding the Majlis to the Revolutionary Regime, the Grand Vizier sent countless diplomats bearing gifts to Grim Torgeir, and before long the two men were in regular correspondence with one another.

And late in 1804, these efforts finally paid off when Ibn Timu announced their alliance to the Majlis. The emirs, sheikhs and walis seated in the assembly were quick to congratulate the Grand Vizier, of course, but there is no doubt that hatred and anger was still simmering. The full might of the Majlisi Guard meant that Ibn Timu was still too strong to act against, but a reckoning would come, sooner or later.

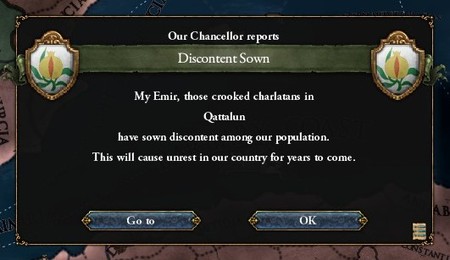

The reaction abroad, on the other hand, was immediate and unforgiving. Despite being a long-time ally of Qadis, Emir Abdul-Rahman of Qattalun broke off all ties with the Majlis upon hearing of the news, refusing to remain allied to them whilst they entertained revolutionary sympathies. And to make matters worse, much to the horror of many seated in the assembly, the emir also began making overtures to the Moroccans.

Working with Almoravid Sultan Issam, the emir managed to open relations with prospective rebels in the islands of Mayurqa - islands that’d been under the governance of the Majlis for almost a decade now. Discreetly working to diminish Majlisi influence in the region, the two Muslim powers began supplying the rebels with funds and weapons, encouraging them to act against the local governor as they did so.

And within a short few months, rebellion broke out on the islands, with a small host marching on and destroying several Majlisi garrisons in the region. From there, they quickly spread to occupy large parts of Mayurqa, demanding that the island be ceded to the Emir of Qattalun.

Ibn Timu was having none of it, of course, dispatching Amir Rale with a sizeable contingent of the Majlisi Guard to crush the revolt. And after disembarking at Port Jizrunid (so-named as it had been the last holdout of the Jizrunids in Iberia), it took all of one day to accomplish exactly that, with the Guard sweeping aside the disorganised peasant rabble and recapturing key towns once more.

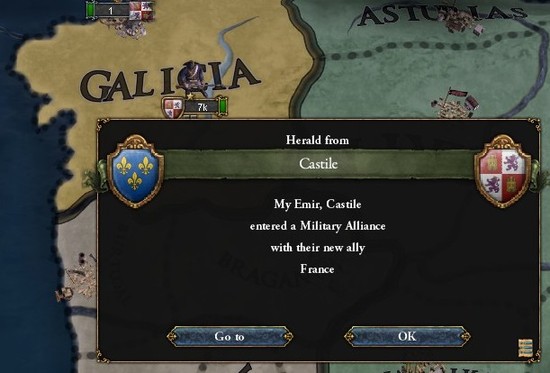

Most of the Majlisi Guard had stayed behind in Iberia, where Ibn Timu was planning his first independent war as Grand Vizier, hoping to conquer Galicia and finally bring about an end to Castilian rule on the peninsula. Just as provisions were being stockpiled and supply lines were being secured, however, word reached Qadis that King Adhémar of France had guaranteed the independence of Castille.

Surrounded on all sides by enemies and with no other routes of expansion, this left Ibn Timu fuming, with observers even claiming that in his anger the Grand Vizier had executed the messengers who’d brought him the news.

As far as King Adhémar was concerned, however, everything was going to plan. With his toehold in Iberia secure, he could devote his resources to realising his ambitions in the new world, with the King conducting a short but successful campaign in the Andes Mountains in the summer of 1805. And after a short round of negotiations, large tracts of Andean land was forcibly ceded to New France, the autonomous French viceroyalty in the west.

And the rampant colonialism didn’t end there, with the Almoravid Empire declaring war on the Charca mere days later, further south.

It was quickly becoming apparent that the era of independent native rule in Gharbia was fast coming to an end, and with the vast majority of northern Gharbia already conquered by the various colonial empires, the race to seize the last unconquered vestiges in the south was on - a great game raging between France and Morocco.

Across the Pacific, meanwhile, the Japanese invasion of the Red Turban State also came to an end. With large parts of Manchuria and Korea were under brutal Japanese occupation, posing a legitimate risk to the Manichean monks who ruled Korea. The ruling class quickly sued for peace, willingly ceding almost the entirety of their northern conquests to Revolutionary Japan, along with the strategic island of Jeju.

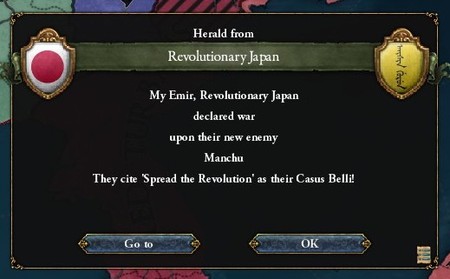

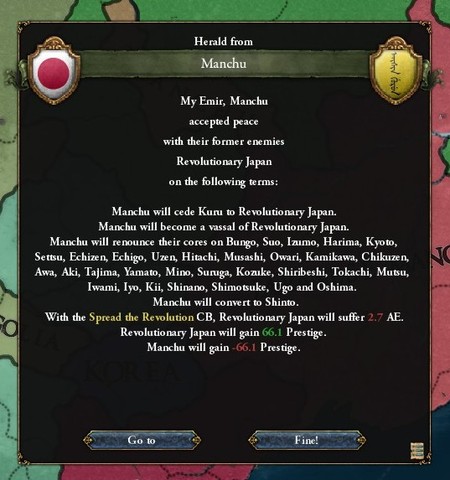

With Korea pacified, the Shushō ruling Japan looked to asserting his control in Manchuria, declaring war on the last remnants of the Manchu Empire in the north. Once rulers over all Japan, this would prove to be the last gasp of the Manchu royal family, with their complete annihilation over the coming months practically set in stone.

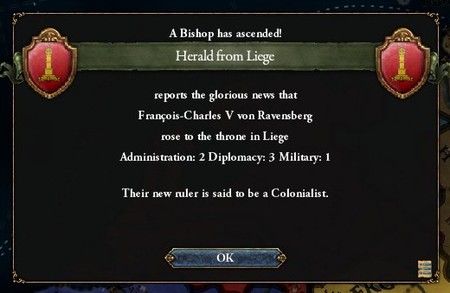

At the same time back in Europe, a new Archbishop was named to the powerful bishopric of Liege, which held suzerainty over large parts of the Netherlands and Flanders.

Unfortunately for him, however, Archbishop François’ reign began with a declaration of war from the south. The Revolutionary Regime in Bavaria had spent the past few years recovering from the War of the First Coalition, and now that they were finally ready to plunge into another series of revolutionary wars, Grim Torgeir launched an invasion of the Low Countries late into 1805.

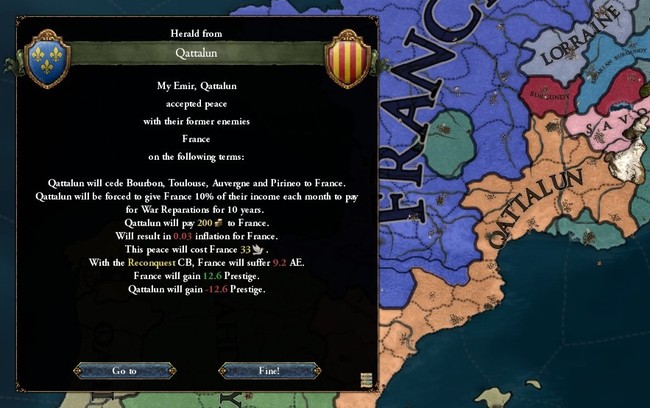

To the south, meanwhile, peace was reached between Qattalun and Provence. The Occitan kingdom was forced to cede vast tracts of Savoy in the ensuing peace treaty, with Qattalun now surrounding the city of Provence on all sides, marking the greatest territorial extent of a Muslim power into Europe throughout history.

Obviously, with the expansionistic emirate now threatening his capital, the king of Provence was forced to move his court away from Provence itself and into Italy. As he did so, he sent an urgent appeal to the Christian powers of Europe, begging for aid in pushing back the Muslim menace and reclaiming his lost lands.

Only one king responded - Adhémar, and he did so with a declaration of war. Just as the autumn of 1805 broke, thousands of Frenchmen poured into Muslim-held Provence, quickly seizing any towns dotting their border and laying siege to local fortresses. And with very few allies to back up the Qattalun Emirate, its immediate prospects weren’t looking too bright.

Back in Qadis, meanwhile, Ibn Timu had continued strengthening relations with Bavaria. In fact, he managed to convince the National Assembly in München to declare the Almoravids their rivals, an important step in ultimately involving the Revolutionaries in Iberian affairs.

That said, there wasn’t much that the Bavarians could do so long as they were focused on European expansion. And whilst the Revolutionary Wars weakened the great powers of Europe, Sultan Issam was busy expanding Almoravid influence all across the Mediterranean, with his massive navy turning Morocco into the world’s most powerful force on the seas.

And the sultan used this power very effectively, and was evidenced later that year, when a new emir was crowned in the Jizrunid Emirate of Palermo. The young Ibrahim-Yah quickly proved himself an able administrator, but eager to prove himself as both a political and military leader, Ibrahim-Yah foolishly led an army northward to recapture Naples just as winter arrived, with the campaign ending in disastrous failure.

The humiliating defeat of his army saw unrest rapidly spike throughout Palermo, eventually erupting into open rebellion as thousands of peasants began rioting, demanding an end to harsh taxes and oppressive rule.

Emir Ibrahim-Yah was forced to reach out to Sultan Issam, with the Almoravid Navy quickly sweeping into the Straits of Messina, transporting a large Berber force to crush the peasant revolt. And in return, the Jizrunid Emirate began paying tribute to the Almoravids, with close ties quickly developing between the two powers.

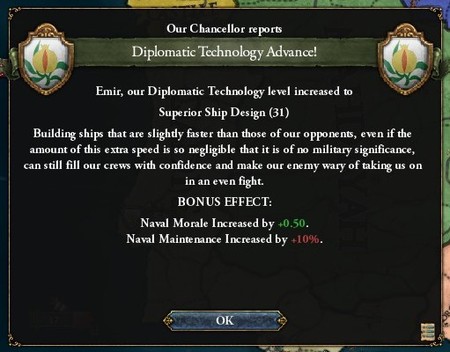

In Qadis, Ibn Timu’s investments into the navy were beginning to pay off, with the war fleet now standing strong at ten threedeckers, with another six still being constructed. Bavarian advisors had been instrumental in the development of new designs, aiding in constructing faster and larger ships than ever before, all of which was important if Qadis was ever again going to challenge Morocco for the straits.

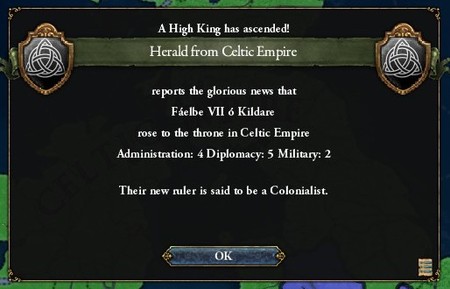

In the north, meanwhile, celebrations were held throughout Ireland as a new high king was crowned in Dublin. Unfortunately for Fàelbe, however, by the time of his ascension the best days of the Celtic Empire were far, far behind.

The decline of the Celtic Empire was almost entirely down to France, with a succession of French monarchs waging constant war against the Celts - both in Britain and in the new world. King Adhémar was no different, not only determined to see himself formally recognised as King of England, but also focused on seeing his colonial rivals humiliated and weakened.

Working towards that end, Adhémar reached agreements with unruly Celtic colonies in Gharbia early in 1807, promising them financial and military aid in the event of an independence war.

In the Near East, meanwhile, a remarkable series of victories saw the Armenian invasion firmly brought to a screeching halt. From there, the forces of the Serbian Republic managed to push the Vakhtani armies all the way back to Thrace and throw them across the Bosphorus, laying siege to Constantinople itself before Sultan Avedis was finally forced to sue for peace.

And the negotiations did not end in his favour, with the Vakhtani Caliphate ceding almost the entirety of its European possessions to the Republic, retaining control over only the city of Constantinople. And even then, the Serbian dictator Dragutin began drawing up plans for an invasion of Anatolia, determined to prove himself an equal of Grim Torgeir.

To make matters worse, news of Avedis’ defeats in Europe quickly spread through the Middle East, inviting Crusader Egypt and the Vali Emirate to launch another invasion of the Armenian Caliphate. The two powers revived their successful alliance just before declaring war, with the Egyptians laying siege to Adana and the Kurds marching on Yerevan, the Armenian capital.

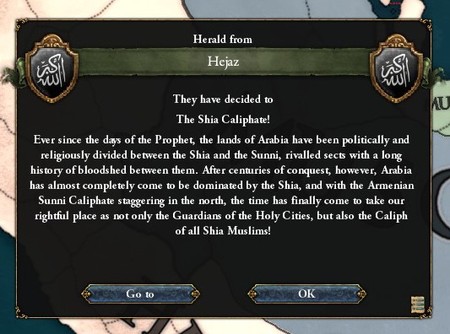

The constant defeats suffered by the Vakhtanis massively damaged to prestige and authority of the Caliphate, which was quickly withering away in power and influence. This quickly became apparent as Shia tribes in Arabia rose to dominate the entire peninsula (and even pushing out to Iraq), where Sunnis once had firm control over the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina.

And as Armenian fortunes declined in the north, those of the Shia rose in the south. No longer satisfied with being the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, the Sharif of Mecca took it one step further and declared himself Khalifa over all Shia Muslims, directly challenging the authority of the Vakhtani Caliphate.

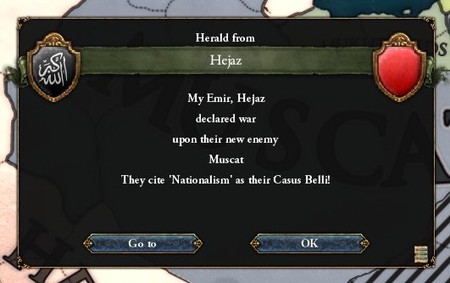

The disparate and varied tribes of Arabia quickly submitted to the authority of the Sharifate Caliph, but one power stood firm and refused to bow: the sultanate of Musqat, direct rivals and foes to the Hejazi kingdom. Determined to unite the peninsula both religiously and politically, the new caliph declared war on Musqat, marching on the city with an army numbering thousands.

In the Far East, meanwhile, the Republic of Japan met with more victories in Manchuria. Upon securing the surrender of the Manchu Emperor, Japanese authority swept across the entirety of Manchuria and parts of Mongolia, with the republic exercising their authority in the form of puppet republics and vassal tribes.

This was the end of a long series of wars seeking to unite Manchuria under a single polity, and now that that was done, the nascent republic finally felt confident enough to begin pushing into China. The Shushō declared war on the Qi Empire in the full summer heat of 1807, bent on seeing Revolutionary forces in Beijing before year’s end.

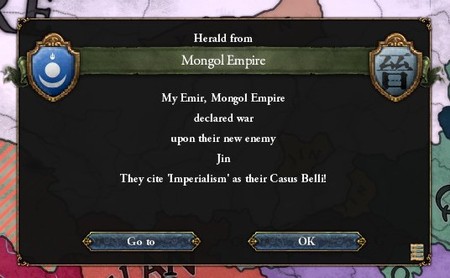

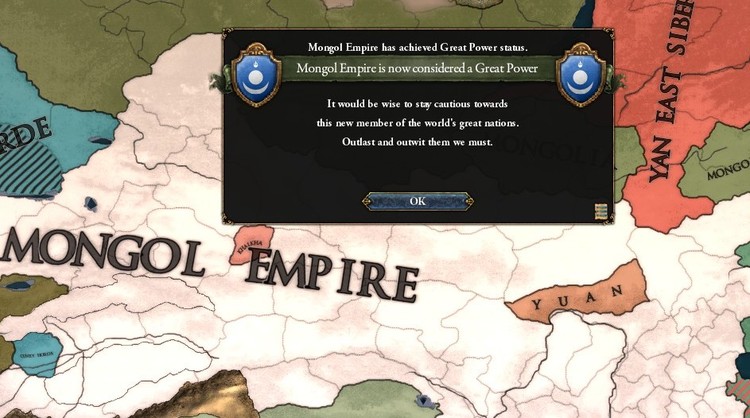

North China was vast and densely-populated, however, and the Japanese would not have an easy time carving out puppet states there. Their chief rivals in securing the Mandate of Heaven were the Mongol Empire, which already ruled over vast swathes of Chinese land, with the Great Khan declaring another invasion late in 1807.

The early days of 1808 was marked by a series of French victories against Qattalun, quickly occupying large parts of the Muslim emirate north of the Pyrenees. And after breaching the walls of the fortress in Roussillon, the aged Emir Abdul-Rahman was forced to surrender to Adhémar, ceding some of his earliest conquests to the French king.

With that, the kingdom of France reached its greatest territorial extent in centuries, ranging from the Pyrenees in the south to the English Midlands in the north, and Finistère in the west to Wallonia in the east. Were it not for the expansionistic Revolutionary Regime in Bavaria, France and King Adhémar would undoubtedly be master over all Europe at this point, dominating the continent from Paris.

The stinging defeat suffered by Qattalun, meanwhile, had immediate repercussions throughout the emirate. Revolutionary fervour once again began brewing in the isle of Corsica, with tensions quickly escalating as a series of raids were carried out against government garrisons, with the Radicals led by one Sahim Tirruni.

The scion of a minor noble family that’d emigrated to Corsica in the 16th century, converting to Islam a few decades after the island’s conquest by al-Andalus, Sahim quickly proved himself an ingenious and resourceful leader as he evaded Qattaluni authorities and masterminded the capture of the island.

Once Corsica was under the firm control of the revolutionaries, anyone suspected of treachery was quickly imprisoned and executed via guillotine, and the chaos only escalated from there. Putting Bavarian subsidies to good use, Sahim Tirruni led a small force of revolutionaries as they successfully crossed the Mediterranean, landing off the coast of Gerona and quickly marching south to besiege Barshaluna.

Emir Abdul-Rahman fled his capital a few days before the Radicals had arrived, fortunately, gathering a large force at Saraqusta to counter them. The revolutionaries would not be so easily suppressed this time, however, with his entire emirate hanging in the balance as the walls of Barshaluna were quickly reduced to rubble.

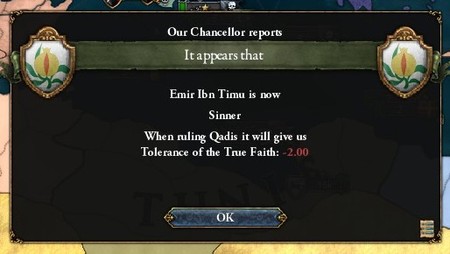

In Qadis, meanwhile, Ibn Timu was quickly becoming a hated figure in the public eye. Bored and annoyed with the antics of the Majlis, and with no opportunities to showcase his battlefield abilities, the young Grand Vizier instead distracted himself by hosting huge, decadent parties in the royal palaces. Rumours quickly spread as Ibn Timu and his officers indulged in shockingly sinful pleasures, sleeping with hundreds of exotic prostitutes, sampling and enjoying dozens of different drugs, drinking and gambling deep into the night.

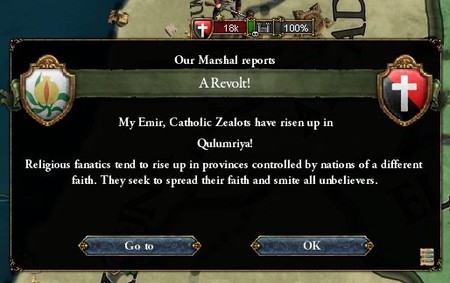

Further west, another large revolt broke out in Portugal, this time a Catholic rebellion in Qulumriya. And this time Ibn Timu, increasingly irritated by the Majlis criticisms and disapproval, chose to personally lead the Majlisi Guard in quelling the revolt, anxious for any reason to do battle.

So he left Qadis and made for the garrisons in Ishbiliya, where he took command of the Guard and began the march northward. The rebels had scarcely managed to capture the city before Ibn Timu arrived, driving into Qulumriya with thousands at his back, giving the rebels no quarter and no mercy as they were cut down in their thousands.

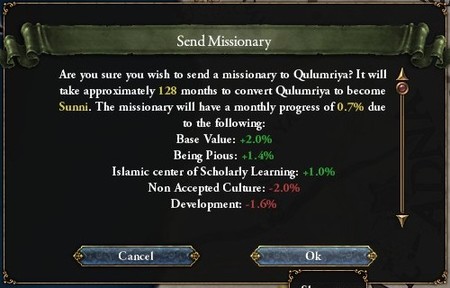

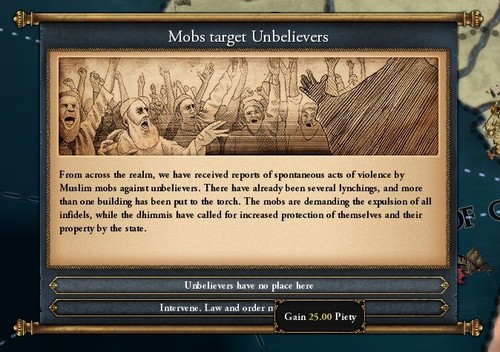

And this time, impatient with the constant Portuguese revolts (and possible under the influence), Ibn Timu didn’t limit himself to simply executing the rebel leaders. Instead, he led a brutal campaign in which the Christian population of Qulumriya was massacred, with the Grand Vizier giving his army two days to sack and kill and loot to their heart’s content. And even after he left the city, his newly-appointed governors did nothing to safeguard the Christians, with Muslim mobs rioting and lynching them on a daily basis.

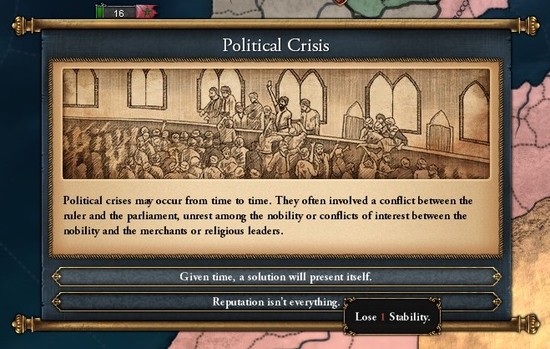

This was met with uproar in the Majlis, with almost the entirety of the assembly protesting the Grand Vizier’s vicious and unprecedented slaughter. Ibn Timu refused to acknowledge his crimes, instead staying in Ishbiliya with his army whilst the political crisis escalated in Qadis, where he was already being called "Ibn Timu the Butcher". Factions began flocking in opposition to the Grand Vizier, calling for his deposition and replacement.

In the east, meanwhile, the recent Japanese incursions into China ended in resounding success. The Qi Empire was a heavily-corrupt and teetering regime, barely able to maintain control in its capital, much less the vast swathes of land over which it claimed authority. Stripping the Qi of its northern territories thus proved no difficult task, with Revolutionary Japan now sweeping down to the borders of Beijing itself.

Posing a more serious threat to Japanese interests, however, was the Mongol Empire. They too had launched a series of invasions into China, with their wars ending in similar success and securing the influence and power that the Great Khan held in the region.

In the Far West, on the other hand, the inevitable finally came about as the Celtic colonies in Gharbia declared independence. Receiving subsidies from France, the Celtic colonies of Albionoria, Anbáila, and Neimní Sund united into a rebellious league in defiance of the Celtic Empire and its allies, which included the Kingdom of New England, a regional power in its own right.

King Adhémar would not personally involve himself in the independence wars, however. His attention was focused in Iberia, where the growing influence of the brutal Mahdist Regime was beginning to worry him, especially as the thousands of Christian refugees pouring into Aquitaine were putting a heavy strain on his own territories.

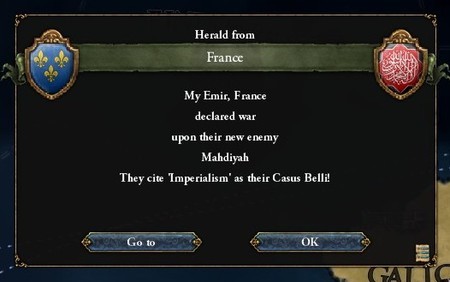

Thus, Adhémar declared war on the Mahdiyah early in 1809, with his chief goals being to push back the theocratic regime and restore Christian rule in Asturias. The war would be no cakewalk, however, with Sultan Issam of Morocco immediately declaring his support for the Mahdi.

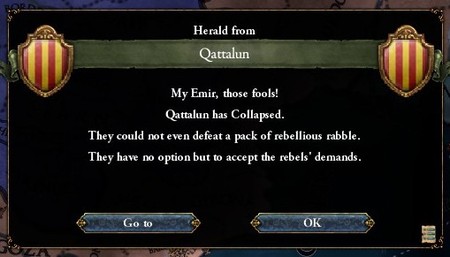

In Qattalun, meanwhile, Sahim Tirruni had managed to pull off a remarkable victory against Emir Abdul-Rahman’s army in a decisive battle just outside Barshaluna. And with monarchist forces relentlessly driven back over the next few weeks, the capital surrendered to Tirruni shortly afterwards, with the radicals flooding into the city and proclaiming the downfall of the Emirate.

From there, Sahim Tirruni conducted a series of campaigns over the course of the next month, brutally crushing any monarchist resistance and capturing large parts of Qattalun, both north and south of the Pyrenees. By the summer of 1709, Emir Abdul-Rahman and his family were forced to flee their emirate altogether, accepting Sultan Issam’s generous offer to host them in Marrakesh.

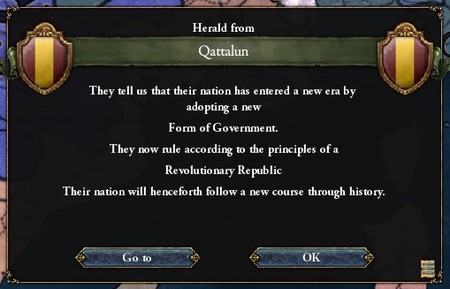

Once the Emir had abandoned his own country, however, any hopes of a monarchist resurgence were dashed. The entirety of Catalonia was brought under the firm rule of the radicals within weeks, with a revolutionary republic declared in Barcelona, where a democratically-elected Shura was founded to represent the people.

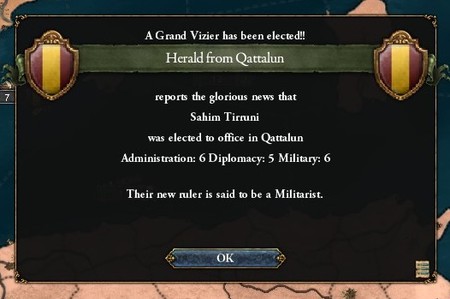

And of course, it was Sahim Tirruni who was declared the first Grand Vizier of the Qattaluni Republic, with the battlefield exploits of the 40-year-old soldier earning him the love and adoration of the peasantry. Sahim’s ambitions are not limited to Barshaluna, however, with the Grand Vizier’s eyes quickly drawn to new conquests in the north…

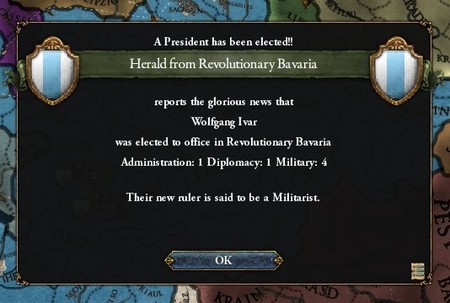

In Central Europe, the Bavarian invasion of the Low Countries finally came to an end late in 1809, with the difficult quagmire of a war ending with another victory for the Revolutionaries. It had come at the cost of tens of thousands of deaths, however, resulting in the National Assembly annexing vast swathes of land along the banks of the Rhine in an effort to justify it.

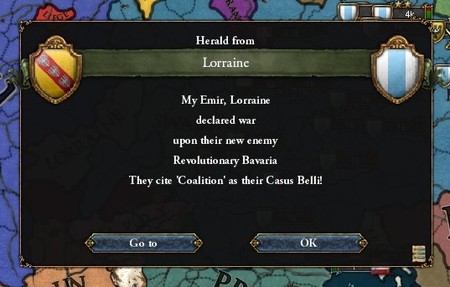

Outrage to this blatant aggression immediately broke out all across Europe, and before long, a Second Coalition began organising in opposition to the Revolutionary Regime. Both France and the North German principalities quickly banded together again, determined to stymie the revolutionary advance but still not confident enough to initiate the war themselves.

That is, until the death of Grim Torgeir. The Bavarian general had led the forces of Radicalism through almost the entirety of the Revolutionary Wars, thundering across Europe in countless campaigns and orchestrating shocking victories out of seemingly nothing, he was the single unifying figure that stopped the Bavarian Republic from collapsing into civil war.

So his sudden death after a short period of illness, of course, dealt a huge blow to the Revolutionary Regime in München.

Questions regarding his succession quickly escalated into civil war in the streets of the capital, and with that, the perfect opportunity to launch the War of the Second Coalition presented itself.

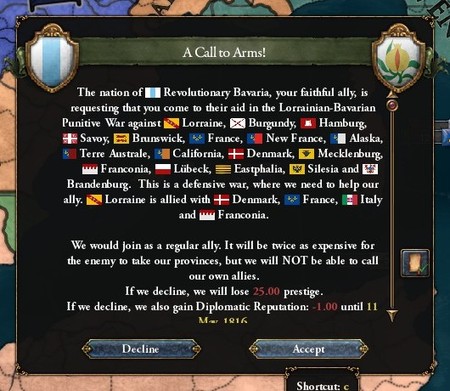

As was expected, the Revolutionary Regime immediately dispatched emissaries to Qadis, requesting the assistance of the Majlisi Guard in the oncoming war.

Ibn Timu rushed back to the capital to receive the embassy, where he wasted no time in accepting the call to arms, desperate for any opportunity to involve himself in the Revolutionary War. The Majlis were powerless to stop the Grand Vizier from doing exactly that, but it didn’t mean they were toothless, with factions within the assembly plotting his downfall even before he left to take command of the Guard.

Revolutionary Bavaria was facing much the same foes it had defeated during the War of the First Coalition, except this time it was internally divided and weakened by years of warfare in the Low Countries. Add exhausted manpower pools and a crippling debt to that, and the odds of somehow emerging victorious for a second time were not looking all that bright.

That said, France was facing even worse odds. Though he had the Second Coalition to assist in the struggle against Bavaria, King Adhémar had no allies to help him push back the Mahdist and Almoravid forces at the same time, leaving his kingdom surrounded by enemies in literally every direction. To add to that, the ambitious Sahim Tirruni declared a war of his own, determined to recapture the lands lost to the French a scant few years past.

And with that, the relative calm of the previous decade suddenly explodes into a continent-wide war, one that promises to revolutionise the political and cultural landscape of Europe, deciding the fate of the old order once and for all. And even as the traditional monarchies clash with the forces of radicalism, younger and far more dangerous powers are quickly on the rise further south, threatening to plunge Europe into its bloodiest and deadliest wars yet.

World map: