Part 67: The March on Córdoba

Chapter 3 - The March on Córdoba - December 1821 to March 1823The early months of war had not gone too well for Grand Vizier Zulfiqar and the Majlis - not a good sign, considering that their very lives would be decided by its outcome. Early victories had quickly been forgotten after a large army of Sunni fanatics overwhelmed the Majlisi Guard, forcing them to withdraw and fall back, before being pinned down and annihilated in another engagement.

1822 thus began with gloomy spirits in Qadis, as the Dictator and the shattered remnants of his army escaped into the ancient city. Some good news did arrive a few days into the new year, however, as a number of depots and storehouses across southern Andalucia were finally completed.

This gave Zulfiqar a lifeline, one more chance to fix things before the Majlis Assembly erupted into open revolt. He quickly sent officers to these new depots, commanding them to begin raising fresh brigades as quickly as was feasible.

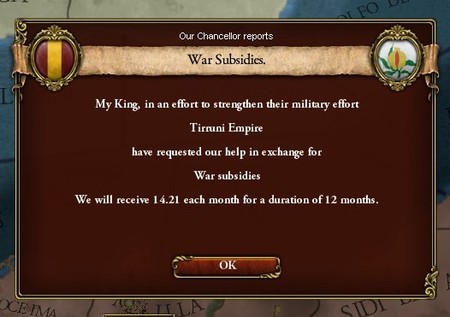

More good news arrived at the capital towards the end of the month, as flamboyantly-dressed emissaries from Sahim Tirruni brought aid in the form of subsidies - clothes, medicine, weaponry and all the other necessities of an army.

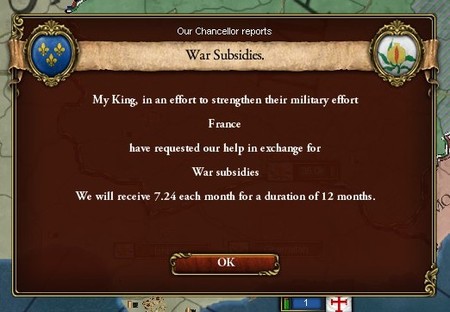

In fact, less than a day later another diplomat arrived, this time from Paris. Queen-Mother Aliç de Valois, who was ruling as Regent until her daughter came of age, was understandably eager to see the Mahdiyyah brought low, and so she also offered the Majlis monthly subsidies over the period a year.

With fresh income and new barracks springing up across the country, a rejuvenated Zulfiqar set about reorganising the army. New infantry regiments and artillery batteries were flocking towards Qadis with every passing day, all green and inexperienced, but they were better nothing.

The remnants of the elite Guard Infantry was shifted to the centre, to aid the fresh recruits in withstanding the terrible onslaught of battle, whilst the artillery brigades remained on the flanks. Before too long, a new army numbering 25000 had gathered at the capital, and Zulfiqar set about actually training them.

And they would need a lot of training, if they were somehow going to push back both the Berbers and the Mahdi’s madmen. The raising of a new army, however, had utterly emptied Qadis’ manpower reserves, so if it collapsed in battle, then all of Iberia would fall with it.

They were the Majlis’ best hope, whether they liked it or not.

The one advantage of losing so many battles was that it had hardened the Majlisi officers, with the many commanders serving under Zulfiqar having learned from their losses against the Mahdiyyah, and now determined to avenge their defeats. Ibn Bibil and Cyrah ibn Cyrah, both of whom had distinguished themselves in early engagements, were promoted to marshals of the army by the Grand Vizier.

Zulfiqar himself was becoming tougher and more dogged than ever, refusing to concede defeat or even entertain the notion of peace, utterly resolute in his belief that Qadis would recover before long. Working towards this end, he demanded the very best from his new marshals, warning them that any failure would be rewarded with life in the oubliette.

And within weeks, these efforts began to yield results, with the newly-recruited boy-soldiers slowly solidifying into an army. With advice from Tirruni’s envoys, the Grand Vizier ensured that his strategists were up to date with the very latest tactics. He also decreased the number of supply trains, instead relying on the country to feed his army, unleashing his foragers on enemy farms and towns to scavenge for supplies and food.

In the north, meanwhile, Tirruni was slowly pushing into Mahdist-occupied Aquitaine and southern France. His massive 120,000-strong army had thus far met with little resistance, with the Mahdi not eager to clash with Tirruni head-on when the odds were so unfavourable.

Even further north, the war raging between France and the Celtic Empire was still in its early days, with neither side able to secure a decisive victory on the battlefield just yet.

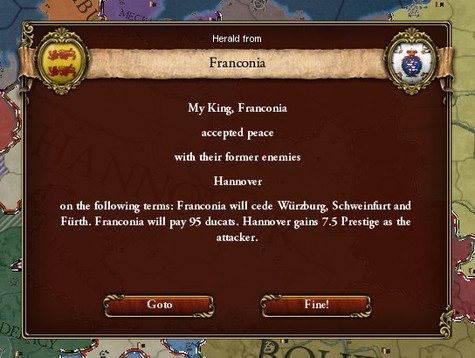

In Germany, on the other hand, a peace treaty had been drawn up between Hannover and Bavaria. The small and disloyal Bavarian army had collapsed after just one battle, fleeing from the field en masse, thus forcing the Archduke to surrender the rich and strategically-crucial city of Nürnburg to Hannover.

Many were surprised by the early peace, and Hanoverian diplomats could certainly have pressed for more concessions, but their reasoning became apparent within a few weeks, with the declaration of war against Franconia. With Bavaria humbled and both France and Novgorod distracted, there was nobody left to defend the tiny principality against the disciplined Hanoverian troops, which stormed across the border early in February.

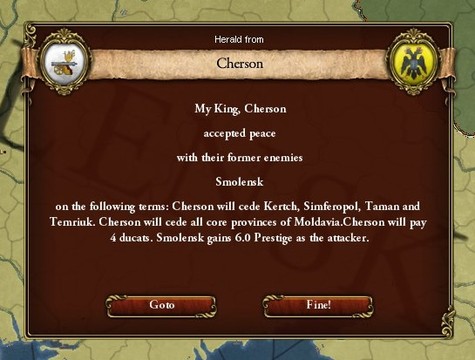

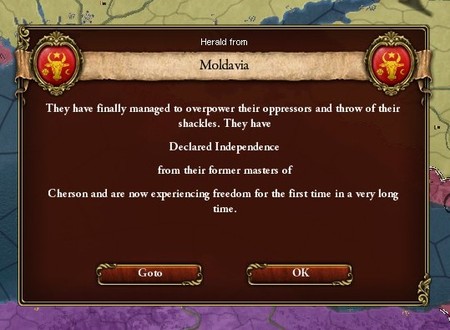

Moving eastwards, another peace treaty was drawn up between Cherson and Smolensk, with the latter desperate to focus its resources against Novgorod. Utterly outclassed by Smolensk’s larger and better-trained army, the Tsar of Cherson was not only forced to cede vast tracts of land in the Caucasus, but also grant independence to the Principality of Moldavia.

Back in the Mediterranean, meanwhile, the war raging between the Almoravid and Tirruni Empires showed no signs of slowing. Early in 1822, the Berbers managed to land a small army off the coast of Cyrenaica, quickly marching on the regional capital of Darnah.

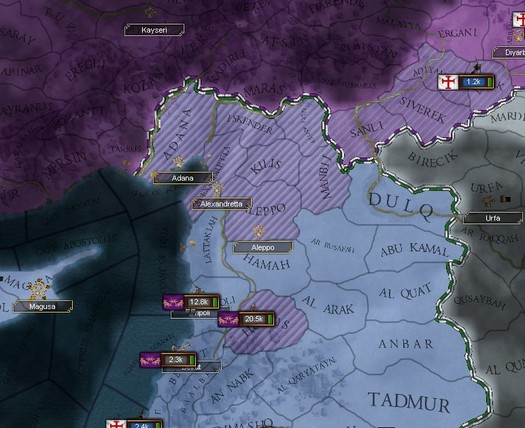

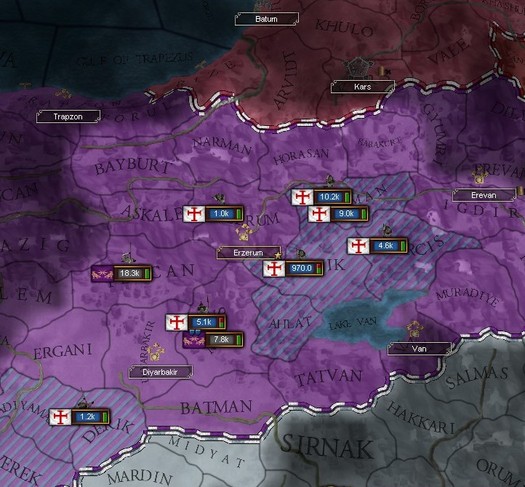

King Apanoub of Egypt, however, did not have the soldiers to throw the Berbers back into the sea. He had another invasion to deal with in the Levant, where a large Armenian army was gradually pushing through Syria, met by cheering Muslim crowds whenever a city was captured.

The young and foolish monarch did not place much value on the rich cities of Syria, however. Instead, hoping to knock the Armenians out of the war in a single offensive, he commanded his generals to launch an invasion of their own, marching into Anatolia and pushing straight towards Erzerum - capital of the Vakhtani Caliphate.

The swelling of war in the East didn’t interest the bickering old men of the Majlis, however. They had a war of their own to worry about, and their squabbling only intensified after Granada fell to the Berbers, a significant blow to both the prestige and finances of the state.

With Granada now in enemy hands, the road to Qadis itself now lay open. To the surprise of the Majlisi noblemen, however, the Moroccan army actually retreated to Qartayannat after capturing the city.

Their reasoning became clear a few weeks later, when Majlisi spies in the north relayed news that the Mahdi was gathering his forces to counterattack against Tirruni, who had managed to solidify his hold on Aquitaine.

As Moroccan and Mahdist armies flocked northward, Zulfiqar finally had an opportunity to strike outwards. Marching his new army out of Qadis for the first time, he ignored the commands of the Majlis and pushed straight past Granada, intent on laying siege to Qurtubah itself.

If Qurtubah fell, the Grand Vizier was convinced, then so would the Mahdi.

At the same time, the First Admiral of the Majlisi Fleet ventured out into the Straits of Gibraltar, which had been near-abandoned by the Moroccans, with only ten vessels left to defend it.

Knowing full well that the straits wouldn’t be left so unguarded for long, Admiral Abu Affi quickly pinned down the inferior force, sinking two ships and capturing another after several hours of heavy gunfire.

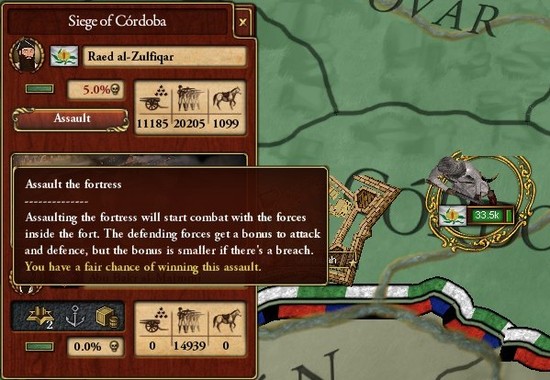

Word of this victory was met with extravagant celebration in Qadis, where the people were eager for any good news at all. Further north, meanwhile, Zulfiqar was slowly but surely chipping away at the defenses of Qurtubah, with his young artillerymen reducing large parts of the walls to rubble after a month of siege.

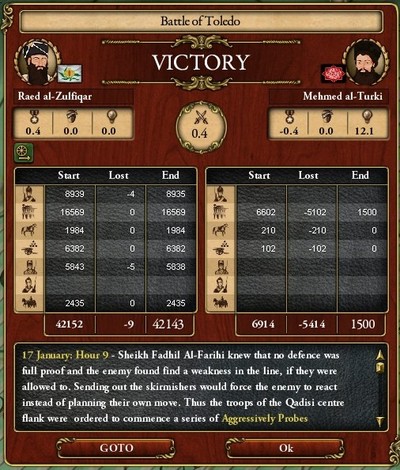

Of course, he wasn’t left to do this in peace. In addition to countless sorties launched from within the city, the Mahdi sent increasingly-large armies southward in an attempt to relieve the siege. The largest of these armies engaged the Majlisi Guard late in April, with the two armies clashing beneath the walls of the city, which were engraved with the sword verses of the Quran.

The battle was long and bloody, and despite losing three men for every enemy killed, Zulfiqar refused to retreat, staying rooted to his position until the Mahdist army was finally repelled. He may have suffered heavy losses, but the Grand Vizier was determined to continue the siege no matter what, pinning all his hopes on its outcome.

Almost a month later, another desperate sortie was launched to try and break the siege, but the soldiers of the Majlisi Guard - who were now hardened with experience - were able to crush it.

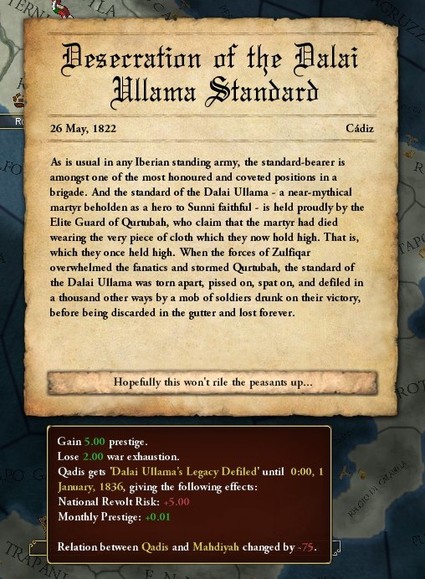

The chaotic battle claimed many lives, however, especially since the Prophet’s Sentinels had been fighting as well. An elite and widely-esteemed force within the Mahdist army, the Prophet’s Sentinels carried the standard of a highly-revered martyr in Islam, but after the standard-bearer was cut down this holy relic was vandalised and defiled by Majlisi soldiers, before being abandoned and lost down some gutter.

The loss of this standard - said to be a piece of the clothing the martyr had died in - dealt a terrible blow to the morale of the defenders. The defenses of the city were still formidable, however, and it took another two weeks of near-constant barrage to finally open a permanent breach in the walls.

It was only then that the Grand Vizier decided to launch a full-out assault, with thousands of screaming soldiers sent pouring through the breach as fighting raged up and down the parapets.

It would take hours of heavy fighting yet, with blood spilt in street and mosque alike - But finally, after six decades of rule under a fanatic despot, the holy city of Qurtubah was recaptured.

Immediately upon entering the city, it was very clear that Qurtubah had changed. All the old statues and extravagant monuments to Jizrunid kings had been torn down long ago, but as the holiest city in Iberia, it was still large and densely-populated. Hundreds of great mosques had been erected throughout the newer quarters of the city, with beautiful marble walkways linking them all and leading the way to the tombs of old martyrs, which were surrounded by airy gardens and promenades. Most magnificent of all, predictably, were the lavish palaces built for the Mahdi and his disciples, circled by manmade rivers and soaring bridges.

All of this would’ve been ransacked and plundered, ordinarily, but Zulfiqar gave express orders against sacking the city. Qurtubah had long been a part of al-Andalus, and would be again, but the trust and cooperation of the populace was necessary to see it so.

As drunken celebrations broke out in Qadis, the war raged on across the Mediterranean without break. Somehow getting past the Moroccan blockade, a small Greek army had somehow captured the island of Sardinia, depriving the Berbers of an important harbour.

Or so it would seem. In actuality, the Berbers had let Sardinia fall, and only because this had left the Greek mainland undefended. With the entire Greek army now trapped on Sardinia, the Berbers were able to send a small force to capture the Peloponnese, meeting little resistance as they pillaged and sacked without constraint.

Back in Iberia, the capture of Qurtubah had bolstered the confidence of the Majlisi Guard, which quickly marched on al-Mansha to the north. Lightly-defended and without provisions, the city fell after just a fortnight - though once again, Zulfiqar kept his troops from sacking it.

A much richer prize lay on the horizon, anyway - Tulaytullah, one of the richest cities in Iberia and Europe, once universally known as the City of Sultans. His dream of reuniting al-Andalus now closer than ever, Zulfiqar quickly had Tulaytullah surrounded, subjecting it to heavy artillery barrage before the night was out.

No Mahdist relief forces arrived to try and break the siege this time, and the reason why was clear: After putting together a huge army numbering 80000, the Mahdi finally engaged Tirruni’s forces in the Pass of Navarre, only to be outmanoeuvred and utterly crushed in the bloody Battle of the Pass.

With the remnants of the Mahdist army quickly retreating into the mountains, and Tirruni’s soldiers swarming across northern Iberia, there was nobody to stop Zulfiqar and the Majlisi Guard from breaching and capturing Tulaytullah within weeks.

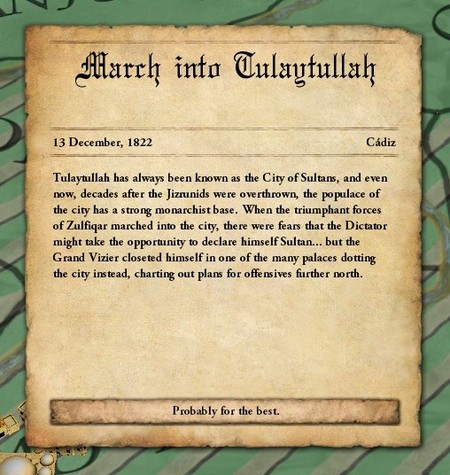

Knowing that the story of this victory would quickly spread to foreign courts, Zulfiqar made a great show of the capture, marching into Tulaytullah at the head of a great parade.

Many members of the Majlis, fearing Zulfiqar’s growing fame and influence, believed that he would choose this moment to declare himself the new Sultan of Al Andalus. Generals were ambitious creatures, after all, and it had happened before. But after congratulating his officers and troops, the Grand Vizier instead closeted himself away in one of the many palaces dotting the city, charting out plans for future offensives.

Zulfiqar, it would seem, had no interest in obtaining a crown. After a few days in Tulaytullah, in which he executed and replaced any Mahdist officials, Zulfiqar set off on another march. The better part of southern Iberia was now his, but he knew there was still a long road ahead, and so wasted no time in capturing the minor cities dotting the west.

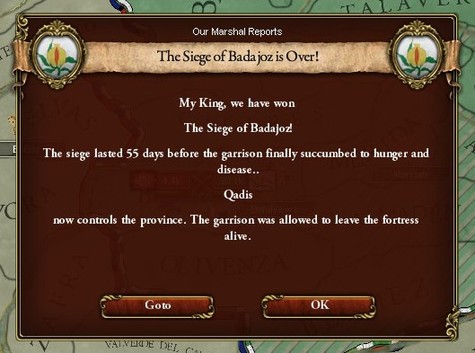

After three months of this, he finally came on the last notable city in southern Mahdiyyah - Batalyaws, once a highly-populated and rich city at the heart of a dozen trade routes, now little larger than a town. The Majlisi Guard, which was weakened in numbers but strengthened in experience and discipline, quickly had the city under heavy gunfire.

In the straits of Gibraltar, meanwhile, Abu Affi saw another opportunity to snatch an opportunistic victory. He quickly embarked from safe shores and engaged a numerically-inferior Berber navy, expecting another easy win, only to be nastily outmanoeuvred by the enemy admirals and forced to retreat with heavy losses.

On foreign soil, meanwhile, peace was brokered between Hannover and Franconia, with the latter ceding rich land to King August-Wilhelm. The Hanoverian king was growing increasingly expansionistic, and seemed to be harbouring dangerous ambitions of somehow uniting all of Germany…

And just a month later, in a move that surprised very few, King August-Wilhelm announced a pact joining Hannover and the Celtic Empire in alliance. No doubt hoping to capture the rich cities dotting the Rhine, the Hanoverian armies quickly flooded into the Confederacy, hoping to overwhelm its sparse defenses before their French overlords could arrive with reinforcements.

And in the south, across field and mount and sea, the Berber expeditionary force had managed to secure the entirety of Egyptian-Libya. And despite numbering only 15000, the Moroccans then decided to besiege Alexandria, though they stood no hope of penetrating the massive city’s defenses without reinforcements, and a lot of them.

The Egyptians, content to leave the Berbers scratching at the walls of Alexandria, had been preoccupied with the Armenians. Having failed to capture the Vakhtani capital, the Egyptian army instead attempted to repel them from Syria, and even this was only partially successful, with the Armenians maintaining their hold on Aleppo and its environs.

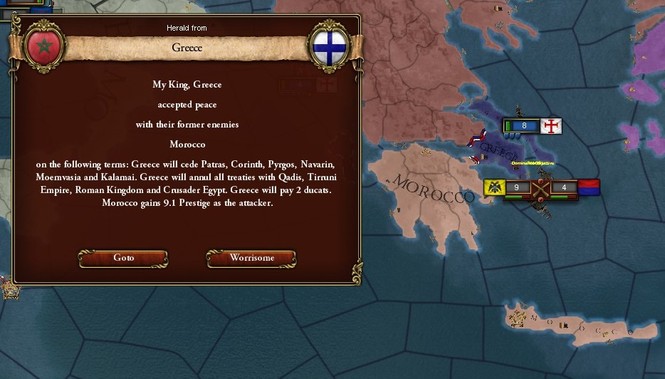

At the same time, the Almoravid Sultan sent reinforcements to Greece, which was quickly overwhelmed by the 30000-strong force over the next few months.

When Athens itself finally came under siege, the King of Greece was forced to surrender unconditionally, with the Almoravids forcing heinous concessions from him. Without even consulting the other great powers, Morocco established a puppet-state in the Peloponnese, only further solidifying Berber influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Shifting back to Iberia, Zulfiqar was still busy attempting to capture Batalyaws, whilst the forces of Tirruni were running amok in northern Iberia. Large parts of Aquitaine and Navarre had already fallen, with captured cities mercilessly subjected to brutal sackings, as Tirruni slowly approached the regional capital of Burghus.

Batalyaws, meanwhile, finally capitulated after two months of siege. As per usual, it was spared a sacking, with Zulfiqar determined to establish friendly relations with the city’s leaders and populace. He was convinced that this was the only way to stitch the two halves of a divided nation back into one.

And this strategy seemed to paying off, with muftis and sheikhs happy to collaborate with Zulfiqar’s representatives. In the more religious cities, however, Sunni uprisings were an unfortunately common occurrence, with the Majlisi Guard frequently rerouted to quash insurrections in Qurtubah and Edeyallah.

In one last desperate attempt to seize control of the straits, Admiral Abu Affi engaged a numerically-inferior Moroccan fleet that had strayed too close to Algeciras. The battle began on relatively even terms, but as the day progressed more and more Moroccan heavy ships joined the struggle, the Majlisi Fleet quickly found itself outnumbered and surrounded.

Not eager to see himself humiliated, Abu Affi hastened to retreat at the earliest opportunity, suffering two sinkings as he tore through a gap in enemy lines.

The seas would belong to the Berbers, it would seem.

In the north, the French had finally managed to defeat a Celtic army and seize Manchester - though relatively small in population and area, the city was especially well-fortified, and its loss would be a difficult blow for the Irish to bear.

On the mainland, meanwhile, the French had managed to rush an army to the Rhine before the Hanoverian army had crossed. Bloody clashes were now erupting all along the river, with both sides doggedly refusing to fall back, clashing in half a dozen cities across the Confederacy.

In Paris, however, one might’ve thought the country wasn’t at war at all. Everything went on as it normally did, with the young and beautiful queen-to-be capturing the heart of the public through her frequent (and widely-publicised) ceremonies, including the opening of the new Imperial University early in 1823.

Across the width of the continent, in the harsh and unyielding climate of Eastern Europe, the story could not be more different. Every man and boy had a gun in hand as the fiercely-rivalled nations of Novgorod and Smolensk battled for the right to Russia, and even with thousands already dead and buried, the conclusion of the war was still far from sight.

In February, Sahim Tirruni announced that large subsidies would be granted to Crusader Egypt, which was suffering heavy losses as it struggled to fight on two different fronts.

The Armenians had managed to seize the upper hand, decisively defeating the Crusader army and capturing large parts of Syria before pushing south, towards the Holy Land. More battles broke out over the next few weeks, all bloody and taxing, but by the end of the month they were at the gates of Jerusalem.

For the Egyptians, this had already gone on for long enough. Diplomats were quickly dispatched for peace talks, and within a month a new treaty had been drawn up, with King Apanoub agreeing to cede Northern Syria to the Vakhtani Caliphate.

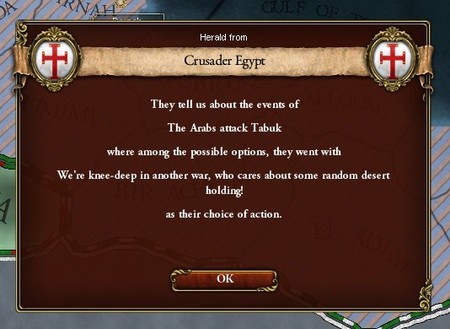

But his troubles would not end there, for scarcely a week had passed before more bad news arrived. The Sharifian Caliph, who had managed to unite large parts of Arabia under a single authority some years earlier, had sent a small force to raid the Egyptian outpost of Tabuk.

Acting on the advice of his ministers, however, King Apanoub did nothing about it. Abandoning Tabuk to the Arabs, he instead dedicated his resources to pushing the Moroccans back from Alexandria.

Already, uncounted lives have been claimed all across the Mediterranean, and we are no closer to war’s end.

The Celts, French, Germans and Russians are all still embroiled in conflicts of their own, but sooner or later they will be forced to intervene in the wars of the south, and suffer for it. The fortunes of Qadis and the Tirruni Empire are on the rise, but even with the Mahdiyyah lost, Almoravid Morocco remains more resolute than ever, determined to end revolutionary rule at any cost.

And indeed, March of 1823 brought bad news for Tirruni, as Moroccan diplomats managed to entice Bavaria and Palermo into joining the war.

At the same time, Berber envoys also arrived at Qadis as tensions begin to grow between Tirruni and Zulfiqar, with many afraid to even imagine what might happen when their two armies meet in the middle of Iberia.

There can be no question about it anymore, this war is about much more than territory and land - it will see old nations perish, it will decide between radicalism and absolutism, and it will determine the new order of Europe for decades, even centuries into the future.

The stakes are higher than ever, and the only thing left to do is fight.