Part 68: Al Andalus Ascendant

Chapter 4 - Al Andalus Ascendant - March 1823 to July 1824In any war of note, there will be terrible losses and glorious victories on both sides before a decisive outcome and peace is finally reached - a delicate balance only tipped in favour of the victors at the cost of brutal sackings, fierce battles and untold deaths.

The Tirruni Wars of the 1820s were no different, and despite a string of early losses, the early months of 1823 saw Emperor Tirruni and his allies finally seize the upper hand. The Mahdiyyah - a stain on Iberia for far too long - had finally fallen to combined invasion, with the Majlisi Guard storming up from the south and Tirruni’s vast hordes descending on the mountains of the north. Heavy fighting and chaotic assaults would follow, but apart from a few isolated holdouts, the entirety of the rich and dense Iberian peninsula was soon captured by the two powers.

Ordinarily, such a devastating loss would’ve been enough to force the enemy to the negotiating table - but these were not ordinary times, and the Almoravids were not so easily brushed aside.

A few weeks after the capture of the Qurtubah, a surprising proclamation was made in Marrakesh, the isolated Berber capital. The Sultan of Morocco declared that the first all-Indian brigade in the Almoravid army would be transported to north Africa, where it would be outfitted and trained in preparation for battle with Tirruni’s forces. This was met with uproar from much of the Berber nobility, but with the Maghreb’s already-sparse manpower now tapped dry, there was no alternative.

Back on the peninsula, meanwhile, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar was busy preparing for his next offensive. Whilst capturing the cities dotting southern Iberia, the retreating Mahdist army had abandoned thousands of supplies and weapons, which the Majlisi Guard was quick to take advantage of by refitting and incorporating them into their own brigades.

After resting his soldiers for the first few weeks of April, Zulfiqar finally moved against the last enemy holdout in the southern half of Iberia: Qartayannat. Determined to throw the Berbers from his peninsula, the Grand Vizier accompanied the army to the very gates of the fortress, relaying orders as they clashed with the small Moroccan force encamped outside the city.

The battle was short and bloody. Bombarding enemy positions hours before even engaging them, the Berbers were crushed over the course of four short hours, with thousands gunned down and the rest forced into chains. By night’s end, the fortress stood ripe for the taking.

Under Jizrunid rule, Qartayannat had never grown very large, with its small port superseded by the Valencia harbours further upcoast. Once it had been captured by the Almoravids in the 1780s, however, no expense had been spared in strengthening its walls and expanding the harbour, transforming the town into a bustling fortress.

Zulfiqar quickly had the fort surrounded by land, but with Berber ships still docking at its harbour, the garrison refused to surrender. So once again, artillery pieces were dragged into position and explosive shells were hurled at its walls, with Qartayannat under siege before night’s end.

Even as the siege began on the mainland, however, the Moroccans landed a small army to capture the Balearic islands. Whilst the Berbers stormed the town of Medina Mayurqa, a small militia was raised from the meagre population of Port Jizrunid, quickly armed with swords and sickles as the enemy approached.

In the north, meanwhile, the French had finally managed to break the Celtic army in the Battle of York. As the shattered Irish withdrew to Scotland, they abandoned England to fall to the enemy in their wake, with city and town alike heavily sacked as the end of the war finally came into sight.

Moving to the East, celebration and festivities broke out in Smolensk as the first Russian Circumnavigation ended in success, an impressive boost to the empire’s prestige and influence on the seas.

There would be much greater cause to celebrate a few days later, however, when Smolenskian troops tore down the gates of Moscow and poured into the city. With Novgorod itself now put at risk, Tsar Vasiliy reached out to the Smolenskian tsarina, offering to meet and discuss peace terms.

And after two months of negotiation, they were finally agreed upon. Novgorod was forced to make heavy concessions, but they still managed to keep hold onto Novgorod and a handful of other important cities, making it clear that the struggle for Russian Leadership was far from over.

That said, all experts agreed that the peace could not last, and would collapse into blood and carnage within a year.

But even so, it could not be denied that Novgorod had suffered a humiliating defeat. Thus, whilst both empires recovered and rebuilt their armies, Tsar Vasiliy declared war on the tiny island-kingdom of Sweden, likely hoping to regain some of his lost prestige.

And the Swedes, of course, had no hope of resisting the vast armies of Novgorod without assistance. Gotland fell within weeks, and with it the last independent bastion in Scandinavia, uniting the entire peninsula under Novgorod. And only further salting the wound, the last King of Sweden was also forced to surrender his title to Tsar Vasiliy, who began making plans for another coronation.

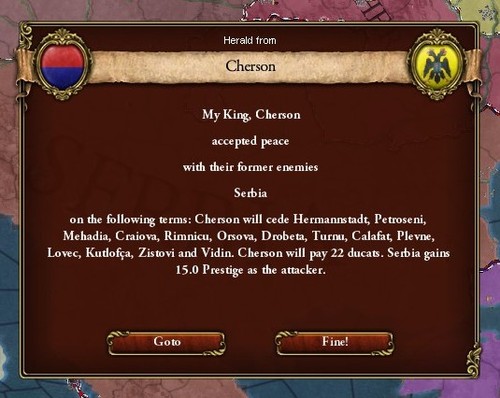

In the Balkans, meanwhile, the unruly armies of the Revolutionary Republic had finally broken through the defensive lines of Cherson and poured across the Danube, mercilessly sacking its cities in punishment for their resistance.

The Serbians would have much more to worry about within a few weeks, however, as a massive uprising broke out in Belgrade late in July. Allegedly in response to police violence, thousands of workers and peasants had rioted their way across the capital, overrunning government buildings and lynching dozens of Revolutionary officials.

As the rioting spread outward from the capital, news of the insurrection was quickly relayed to the frontline, where peace was made with Cherson on harsh terms. The army was then rushed back to Belgrade, where the popularly-elected Consul was overthrown and a military dictator installed, bringing the republic to a bloody end.

And finally, moving across the Mediterranean and to the arid deserts and rolling hills of Cyrenaica, the Berber army had finally been driven from Alexandria and into neutral Libya. The Egyptian army had suffered heavy casualties, but their confidence was soaring after the victory, and so they wasted no time in laying siege to Darnah again, intent on recapturing its valuable harbour.

At the same time, the Berbers were continuing their assault on the Baleares, with Medina Mayurqa finally falling late in 1824.

Once the island was well-garrisoned with fresh troops, the Berber army made the crossing and stormed the beaches of Minorca, quickly capturing them within mere hours. From there they marched on Port Jizrunid, where bitter fighting broke out with the town’s militia.

Of course, a newly-raised militia with no training and scarcely any guns didn’t stand a chance against the Berbers, and were cut down in a bloody massacre. By the end of the day, the Moroccans had seized control of Port Jizrunid, commandeering any Majlisi vessels and opening the harbour to friendly shipping.

Needless to say, this was a humiliating blow to the Majlis, but there was little that could be done about it. They still had a respectable enough fleet, but Admiral Abu Affi had been demoted after his many losses to the Moroccans, and many doubted that the navy would be able to do much without his leadership.

He was replaced by one Sayf al-Talasi - less talented than Abu Affi, to be sure, but Sayf’s ingenuity on the seas would more than make up for it. The new Grand Admiral adopted a guerrilla strategy whereby open battle with the Berbers was wholly avoided, with resources instead devoted to harassing enemy shipping in rapid hit-and-run attacks.

And before long, the victories began to mount.

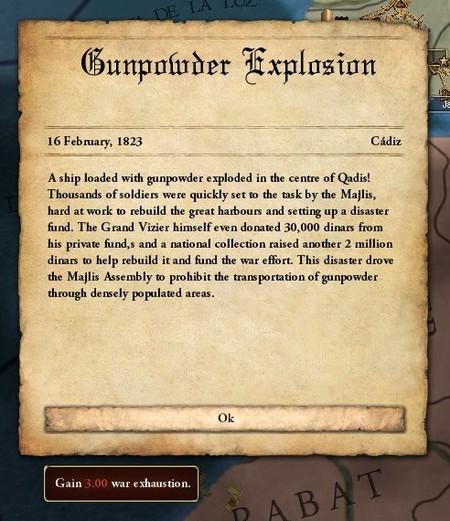

It was in the aftermath of one of these hit-and-run attacks, whilst the Majlisi Fleet was anchoring at the Qadisi docks, that a terrible explosion tore half the harbour apart and set the other half afire. Within hours, hundreds were dead and dozens of warships were sunk, with the damage quickly spreading as chaos fuelled mad hysteria.

A number of nobles, including the Grand Vizier himself, were quick to pledge thousands of dinars to the reconstruction of the harbour in an effort to calm the populace and begin the recovery from the disaster.

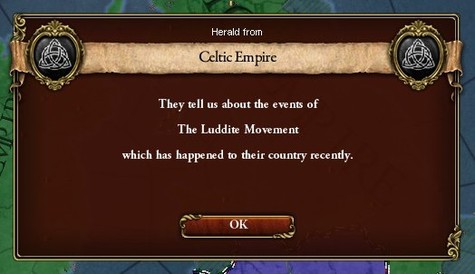

Moving northward, meanwhile, tensions were quickly rising in Britain as the Luddite Movement gained momentum. Driven into poverty by the war with France, Luddites were large bands of desperate workmen who set factories aflame and destroyed machinery, determinedly opposed to the industrialisation of Britain.

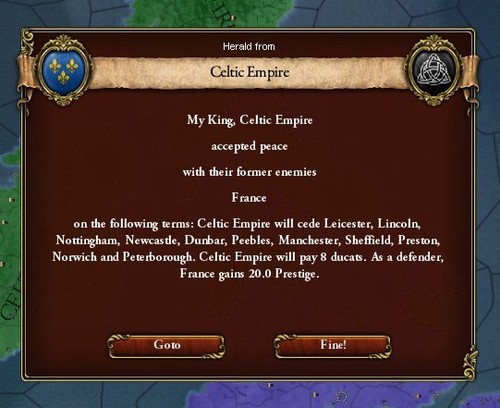

With the war with France gone sour and insurrections breaking out across his empire, King Fáelbe ó Kildare was finally forced to concede defeat, dispatching emissaries to Paris with peace terms. The final terms of the treaty were not to be agreed on for many weeks, however, with the High King ultimately forced to cede the disputed territories, as well as surrender any claim to the title of King of England.

Now free to deal with the Luddites, the riots and revolts were quickly quashed, with any upheaval dealt with harshly. Once opposition to industrialisation was crushed, the High King authorised the construction of factories all across Ireland and Britain, largely concentrated in the more-populous home island.

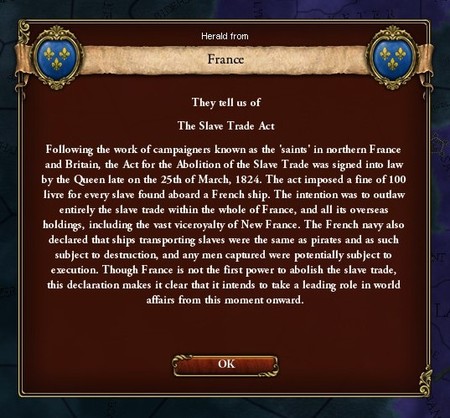

In France, meanwhile, the victory was met with raucous celebration all across the country. The Queen’s allies used the distraction as an excuse to force a heavily-contested bill into law, proclaiming the Slave Trade Act early in October. Though slavery had already been abolished in France, this law extended the abolition to all of the kingdom’s overseas colonies and holdings, and declared that any shipping transporting slaves would be treated as unlawful piracy.

Few doubted the intention of this law - it was a clear challenge to the largest slaveholding empire in the world, with France throwing the gauntlet down at Morocco.

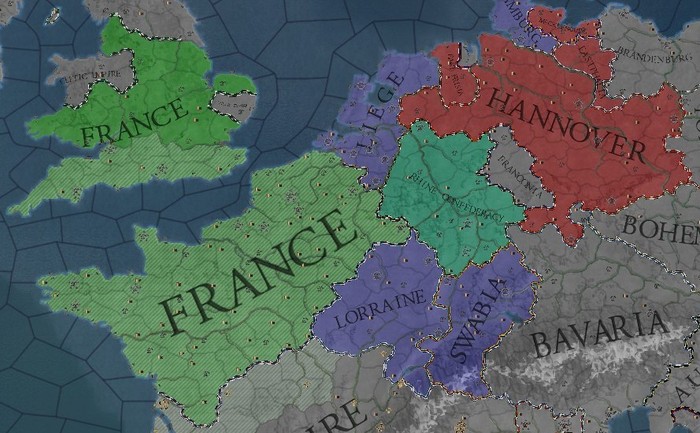

The French, like the Moroccans, were nevertheless distracted by other enemies. Though peace had been reached with the Irish, it didn’t include the Germans, and so the two powers were still clashing in futile attempts to secure the Rhineland.

The Moroccans, on the other hand, suffered another setback in March. With the help of large subsidies from Tirruni, the Greeks managed to rebuild their army before declaring war on the Almoravids, overwhelming the Berbers defending the Isthmus of Corinth and pouring into the Peloponnese.

Because the war against Iberia and Egypt had intensified, the Almoravids left the Peloponnese sparsely-defended, allowing the Greeks to quickly seize control of the peninsula before the new year. The Moroccans would not treat with them, however, instead sending regular dispatchments to try and retake the peninsula.

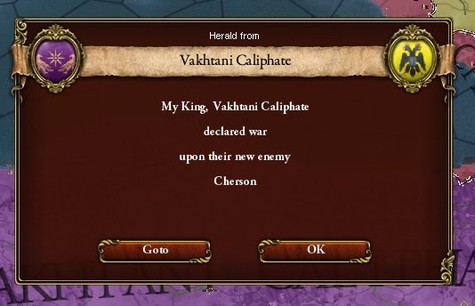

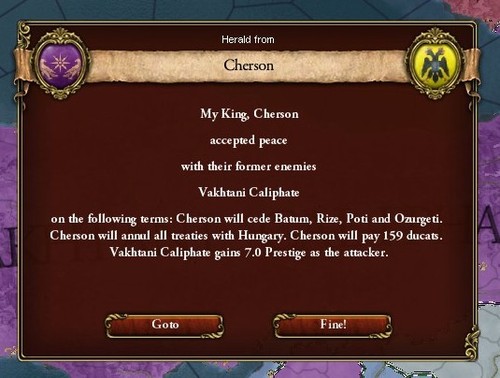

Further east, meanwhile, the new year also saw the Vakhtani Caliphate declare war on a greatly-weakened Cherson.

Having already suffered disastrous defeats to Smolensk and Serbia, the shattered remnants of the Cherson armies were quickly crushed and scattered to the Caucasus. Peace was made within weeks of the war’s outbreak, with the Caliphate regaining yet more lost land and prestige.

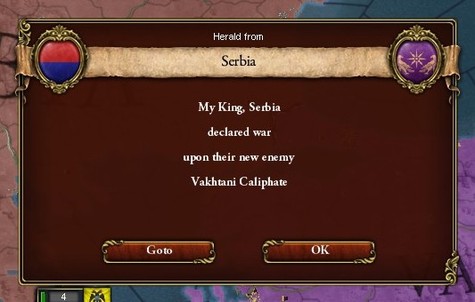

The Armenians would not have much time to revel in their victory, however. Denouncing the unfettered Vakhtani aggression, the new dictator of Serbia declared war late in February, vowing to overthrow the Caliph and install a revolutionary republic.

And within days, it became clear that this would be a long and bloody war. Vicious battles broke out all along the Aegean coast, even as artillery began bombarding the walls of Constantinople - a small and plague-ridden city well past its glory days, but nonetheless hugely symbolic.

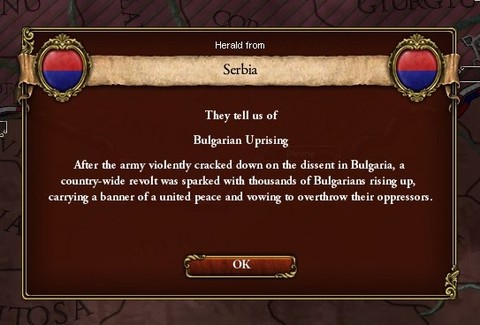

The Serbs would not have an easy time of it, however, because unrest and agitation continued to bubble all across the Balkans. Though the Belgrade insurrection had been violently suppressed, it only fuelled another uprising, with thousands of Bulgarian peasants attacking Serbian authorities in a well-timed attack.

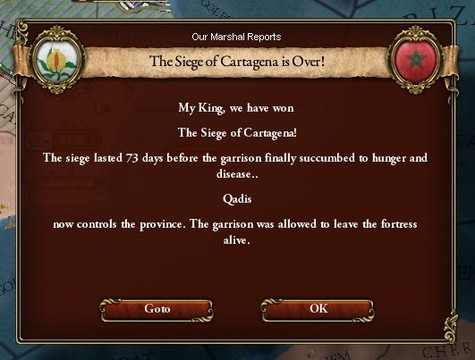

Across the width of the Mediterranean, the ceaseless bombardment of Qartayannat was finally rewarded with a breach, and Zulfiqar unleashed his thousands to pour into the fortress.

Once inside the walls, there wasn’t any strategy that could stave off the superior numbers of the Majlisi Guard, and the Berber garrison was quickly surrounded and slaughtered. And with that, the last enemy holdout in southern Iberia fell to the Grand Vizier, and thus the Majlis.

Zulfiqar wasn’t done yet, however, rushing northwards with all the haste 40,000 men could manage. He’d hoped to capture one or two more cities before confronting Tirruni, but it was too late, as the Emperor had already managed to secure the entirety of northern Iberia whilst the Majlisi Guard was besieging Qartayannat.

By late March, only León stood free from Tirruni’s grasp, with the Mahdi holed up in one of its many palaces and desperately throwing men at the besiegers.

His efforts would prove fruitless, however, as even León fell within the month, its walls collapsed to rubble by the Tirruni’s guns. The famous city was brutally sacked over the next few hours, and in all the chaos brought on by the pillaging and plundering, the Mahdi managed to smuggle himself out unnoticed, accompanied only by two of his disciples.

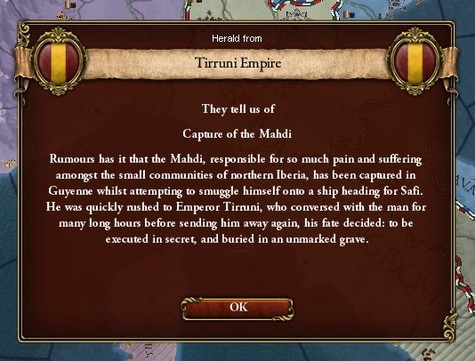

The Mahdi stole across the mountains of Asturias, but he wouldn’t get much further than that, apprehended by guards whilst attempting to steal himself onto a ship heading for Safi.

The Majlis’ demands that he be handed over to them for trial were denied, and this was last that anyone heard of the infamous Mahdi, with everything coming after mere hearsay. According to rumour, however, he was brought to the court of Tirruni himself, where he conversed with the Emperor for several long hours before being taken away, executed in secret and buried in an unmarked grave. Far too kind a fate, as is so often true for men of his kind.

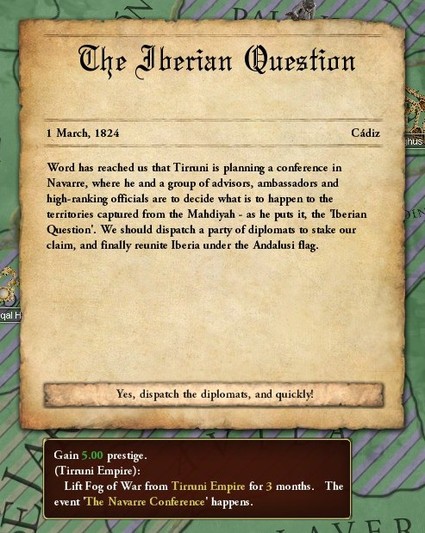

The nobles of the Majlis protested loudly, insulted by Tirruni’s apparent indifference. Their complaints were quickly drowned out by more important matters, however, as news reached Qadis that the Emperor was planning a conference to discuss the fate of Iberia.

In this, the Majlis was united: all of Iberia ought to be under their control, as it had been in the days of al-Andalus. Over the course of the Navarre Conference, however, several other alternatives were put forward, including granting independence to the petty kingdoms that had once ruled in northern Iberia.

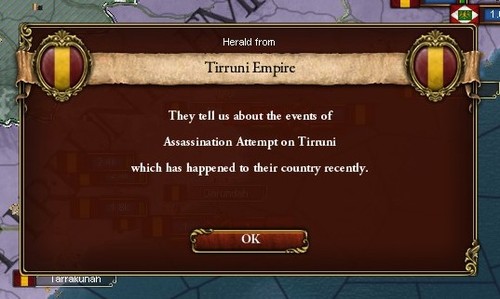

The arguments and disputes and quarrels lasted for over a week, and yet the conference was no closer to reaching an agreement. More complications arose when the discussions were suddenly interrupted after the eighth day of the conference, when an assassin attempted to gun down Sahim Tirruni whilst he was on his usual evening walk. Fortunately, the bullet hit one of Tirruni’s ministers instead, and the assassin was quickly shot down before he could fire again.

As the would-be assassin died on the spot, any possible perpetrators went undiscovered. Tirruni was whisked away from Navarre all the same, bringing the conference to an unexpected end. The fate of Iberia, however, would not be left undecided.

A few weeks later, the Emperor announced that a new puppet-state would be set up to rule all territories captured from the Mahdiyyah: the aptly-named Iberian Kingdom. This declaration, of course, incited anger from almost everyone who’d attended the conference, loudly condemning it as nothing more than rampant expansionism.

And as though that were not enough, Tirruni went on to declare that his second son would rule as King of Iberia in his stead. A cruel and brutish youngster, Qays set off for Burgos without delay, intent on suppressing and punishing the people for the attempt on his father’s life.

The Grand Vizier had rushed straight to Qadis after the conference, and was met with angered uproar as he entered the Majlis Assembly. Once he quieted the frenzied nobles down, he assured them that Tirruni’s declaration would not go unanswered, not by a long shot.

And in early May of 1824, under the sweltering summer heat of Qadis, the rebirth of al-Andalus was proclaimed.

The announcement was made just after dawn, and even as celebration broke out all across the capital, riders were sent in every direction to carry the revelry to other Iberian cities. Emissaries were dispatched to foreign courts, including Marrakesh and Narbonne, to inform officials and sultans of the pronouncement. Vessels carrying neutral colours cut across waves and storms without rest, mooring at distant harbours and carrying the news with them.

Before the day was out, all of the world would know of the revival of al-Andalus.

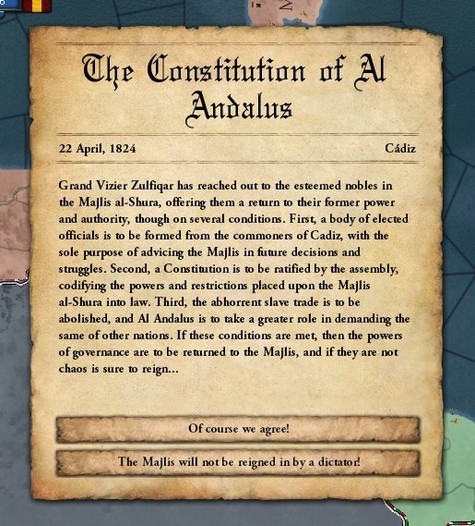

And even then, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar wasn’t done. He addressed the Majlis al-Shura the very next morning, informing them the time to transition power back to the assembly was fast approaching, and that he would do so willingly.

That said, he had conditions. First, a popularly-elected lower house was to be established, with the sole purpose of advising the upper house in future decisions. Second, a Constitution is to be ratified by the assembly, codifying its new powers and restrictions into law. And lastly, the slave trade is to be formally abolished, and the reborn al-Andalus is to take a leading role demanding the same overseas.

Agree to all of this, Zulfiqar said plainly, and the powers of governance would belong to the Majlis once more.

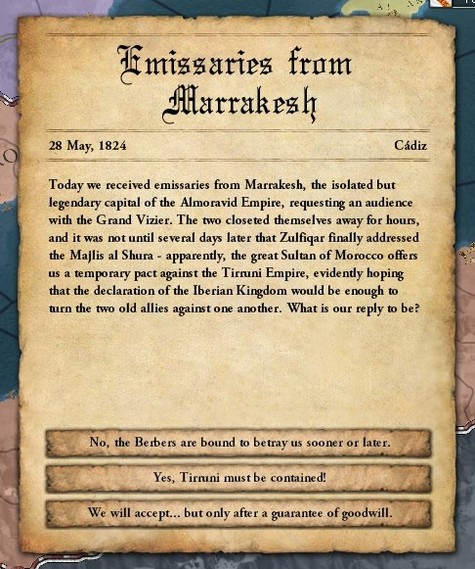

Loud arguing immediately filled the assembly hall, and the Grand Vizier promptly excused himself, hoping to retire until the next morning. Before he could return to his rooms for some much-needed rest, however, he was met with the surprising arrival of Moroccan diplomats.

Apparently, the Almoravid Sultan was pleased to recognise the revival of al-Andalus, and was keen to extend a hand of friendship. With his war going bad and tensions erupting between Zulfiqar and Tirruni, the Sultan also offered Zulfiqar an alliance against the warmonger, promising grand rewards in exchange for betraying Tirruni.

The Grand Vizier excused himself, carrying his troubled thoughts to his bed, where the words of a new speech to the Majlis already began forming. Whatever decisions were made over the next few days, there was little doubt that they would test the strength and longevity of this new al-Andalus.