Part 73: An Imbalance of Great Powers

Chapter 9 - An Imbalance of Great Powers - January 1833 to January 1835Sahim Tirruni had locked horns with the Almoravid Empire for well over a decade, contesting their dominance in the Mediterranean over a series of coalition wars that cost millions in lives, and came out on top near every time. Tirruni not only crushed the many African, Iberian, Indian, French and German armies sent against him, but he also seized vast tracts of land as he did so, building an empire that stretched from Galicia to Istria.

There were drawbacks to this aggressive policy, however, as Tirruni gradually alienated all of his neighbours - and in January of 1833, it finally culminated in a new foe rising to challenge his supremacy. The Russian Empire, young but powerful, had joined the war.

And the first battlefield to see blood spilt was, inevitably, the drenched plains of northern Italy. Russian armies had already secured military access through Austria, and before the month was out, tens of thousands were swarming across the border.

Along with 18000 Hungarians, a 50000-strong Russian army crossed into Tirruni-occupied Venice in February of 1833. The coalition forces managed to capture Lienz after a short siege, but that was as far as they got before Tirruni arrived, at the head of almost 100,000 men.

The Hungarian army occupying Lienz was crushed within days, and once the fortress was recaptured, Tirruni pushed eastward on a forced march. He was determined to pin the Russian army down and seize the initiative, to the bewilderment and surprise of Russian generals, who’d expected the emperor to be on the defensive this time around.

Taking full advantage of this costly lapse in judgement, Tirruni annihilated the Russian army over the course of four bloody hours, bringing their first invasion to a decisive end.

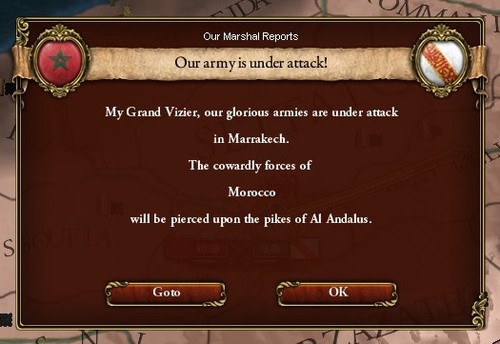

At the same time, however, the Andalusi were engaged in a brutal battle below the walls of Marrakesh.

The Andalusi had spent the past few years on a conquering spree across Morocco, setting dozens of cities and towns afire over the course of their campaign, and seizing unfathomable amounts of treasure and loot as they did so. Their grand goal was Marrakesh itself - the isolated city - but the small Andalusi army scarcely had enough time to pillage its royal palaces before a large Berber army had descended on them, vindictive and vengeful.

And now, caught beneath the walls of Marrakesh and 55000 Berbers, the campaign came to its inevitable end.

Sheikh Fadhil al-Farihi, the commander who’d earned enduring fame for his exploits during the campaign, did all he could with the situation. He managed to deal considerable damage to the enemy in the early hours of the battle, but as the sun peaked and the day waned, his smaller force was slowly but surely forced backwards.

And when night finally arrived, the Majlisi Guard broke, with order and discipline collapsing into chaos and mayhem.

10,000 Andalusi were cut down before the walls of Marrakesh, with the rest fleeing the battlefield in a futile attempt to survive. The Berber army pinned down the survivors a few miles east of the capital, and in a much shorter battle, massacred them all.

An army numbering 45000 had landed at Rabat in June of 1828, and five years later, every last man was dead.

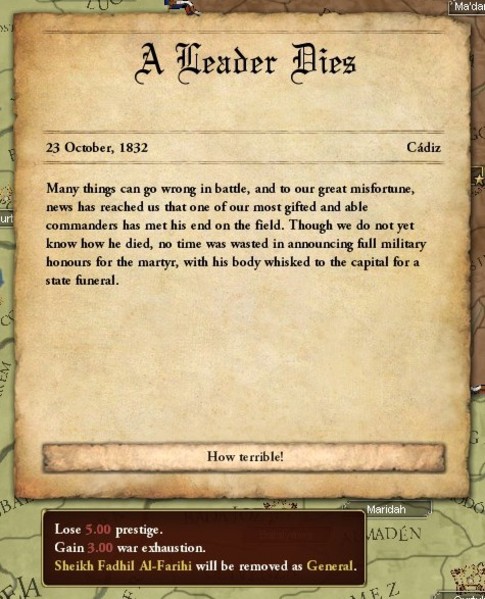

Sheikh Fadhil al-Farihi, for all his prestige and fame, was no different. The commander disappeared just as the battle of Marrakesh turned against him, but there was no escape for any Andalusians, and he would resurface within a few days.

Or, more accurately, his head would. The sheikh had attempted to surrender to the Berber tribal leaders, who promptly decapitated the man who’d ransacked and raped their lands, before sending his head to Marrakesh. There, the rotting and festering head was paraded through the city on a spear, bringing the tale of Sheikh Fadhil to a gloomy conclusion.

Meanwhile, back on the battlefields of Venice, the Russians had launched a second invasion into the Tirruni Empire. This time numbering 90000 soldiers, the Russian army hurtled into Lienz and utterly crushed the Iberian army stationed there, leaving no man standing.

Emperor Tirruni, who’d anticipated a swift retaliation from the Russians, quickly moved to counterattack. He had an army camped near Venezia, and as soon as word of the fall of Lienz reached him, he rushed northward to meet them with all his strength.

Overall, Tirruni’s army was at a numerical disadvantage, but tactically he was well ahead of the Russian leadership. After almost a week of careful reconnaissance, the opposing armies finally met in what would be one of the bloodiest battles of the Tirruni Wars, with over 90000 men losing their lives or freedom over the next few days.

As the first day of April dawned, however, it was Sahim Tirruni who emerged victorious. The shattered Russian remnants hastily retreated back into Austria, where the Emperor broke off his chase and return to his own territories, triumphant yet again.

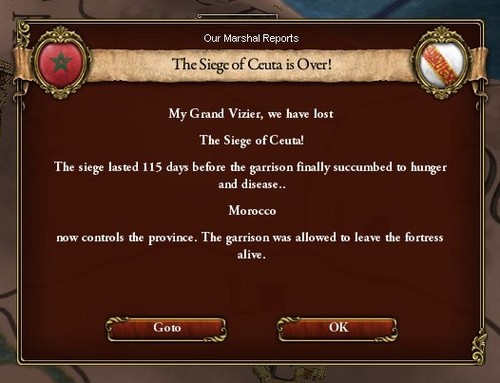

Back in Morocco, meanwhile, Sultan Yahya had returned to his residences in Marrakesh once order was restored. The wars of the last decade had been hard on his health, and now determined to see them end before his death, the Sultan gave the order to march on the last Andalusi holdout in North Africa - Ceuta.

Back in Qadis, meanwhile, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar was just as eager to see an end to war. And whilst he held Ceuta, he still had some leverage in any discussions, so the Grand Vizier sent diplomats to begin negotiations for peace with the Almoravid Sultan.

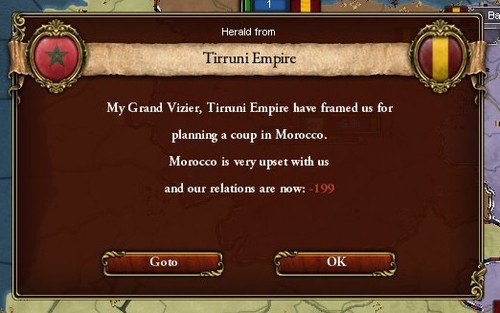

It didn’t take long for whispers of these peace talks to reach Tirruni, however, and the Emperor was having none of it. Several weeks of slow negotiation were thus brought to an abrupt halt when Andalusi ambassadors were expelled from Fes, with Sultan Yahya publicly denouncing the ‘underhanded’ Andalusi for attempting to engineer a coup in the city.

Of course, the Andalusi had done nothing of the sort, but they could do little but protest as they were hastily escorted out of Fes. Zulfiqar decided to refrain from any further contact with the Moroccans, for a few months at least, until relations between the two neighbours had cooled.

Unfortunately, however, Ceuta couldn’t withstand the Berbers for that long. The fortress fell to the enemy late in June, and with it, the last vestiges of the African Campaign were lost.

Across the width of the Mediterranean, meanwhile, the Balkan peninsula was embroiled in its usual chaos. The Serbian Revolutionary army had been decisively crushed by the much smaller, much weaker Greek army, exposing the fragility of the Republic for all to see.

And eager to take advantage of the power vacuum, both Bulgaria and Morocco declared war on Serbia early in July, only further complicating what would later be called the Balkan Crisis.

In an effort to concentrate their forces against a common enemy, a temporary truce was reached between Morocco and Greece. The Greeks would not abandon their claims to the Peloponnese, of course, but they would need time to expand, recover and rebuild before taking the fight to the Almoravids once again.

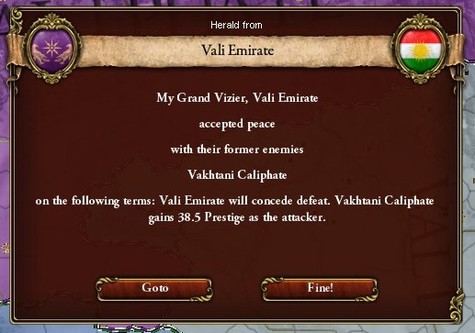

Further east, meanwhile, the Vakhtani Caliphate had managed to repel the invading Kurdish armies of the Vali Emirate. In fact, with the Serbians no longer a threat and the Egyptians distracted, the Armenians were able to go on the offensive and crush the Kurds over the course of several bloody battles.

Thus, after a desperate retreat back into friendly territory, the Kurds were forced to come to terms with the Vakhtanis, with Emir Vali conceding defeat and recognising the spiritual authority of the Caliph.

And now, the Vakhtani had only one more enemy to deal with - the Egyptians. Armenian armies began retaking their lost holdings late in July, quickly recapturing vast tracts of Anatolia and pushing down to Aleppo before meeting any real resistance.

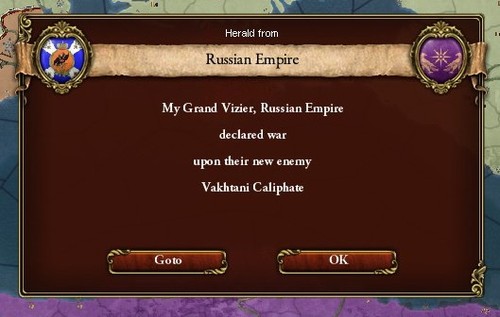

Unfortunately, however, nothing is ever so simple for the Anatolians. Just as Armenian forces lay siege to Aleppo, emissaries arrived in Erzurum, hailing from Smolensk and carrying a declaration of war.

Seeking unfettered access through the Bosphorus, Empress Dobroslava had authorised war against the Vakhtani Caliphate, with thousands of Russians streaming into Anatolia within days.

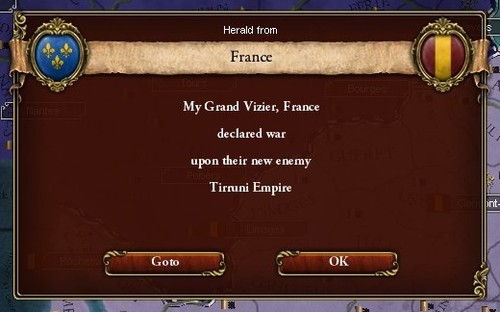

August of 1833 saw the world’s attention quickly shift back to Europe, however, with yet another declaration of war. Addressing an array of subjects and envoys, the unified parliament of France-England declared war on the Tirruni Empire in the early hours of the morning, citing the need to end the perpetual instability in Europe - instability primarily caused by Sahim Tirruni.

Of course, it was a bit more complicated than that. Emperor Tirruni was still seeing success on the battlefield, but he was also more isolated than ever, with enemies and foes in every direction. Furthermore, the ‘Dual Monarchy’ of France-England had been at peace for years now, and with vast manpower and money reserves stockpiled, they were ready to take the fight to the enemy.

Tirruni was now facing the combined forces of Morocco, Russia, Hannover and France-England. Even with his tactical prowess and strategic genius, this imbalance of great powers meant that the odds were firmly stacked against him, with his resentful rivals swarming in from every direction.

The following weeks saw French armies pour across the border and into Occitania, easily crushing the sparse garrisons and token forces that Tirruni had installed in the region.

At the same time, the Almoravids launched a renewed offensive against the enemy. Whilst Sahim Tirruni began a forced march westward, the Almoravid Navy landed a large army at Venezia, numbering over 35000 experienced soldiers.

As for the Andalusi, when word reached them of this new offensive, the Grand Admiral felt secure enough to begin tentative operations in the Straits of Gibraltar. Only attacking when the odds were firmly in their favour, the Majlisi Fleet began seeing some success again, sinking dozens of Berber warships over the course of 1833.

In fact, the navy even engaged two large Russian expeditions to the Mediterranean. The Russian fleets had been sent all the way from the Baltic Sea, but they’d scarcely entered Iberian waters before being met by the Majlisi Fleet, which managed to seize two costly but important victories.

Back in north Italy, the Moroccan offensive was a massive success as both Venezia and Verona were captured, with Mantua besieged late in October. That was as far as they got, however, before Tirruni dispatched a 40000-strong force to finally end their advance.

And that’s precisely what they did, with the Berbers quickly pushed back to Venezia and hastily retreating into the Adriatic after being dealt a decisive defeat just outside the City of Canals.

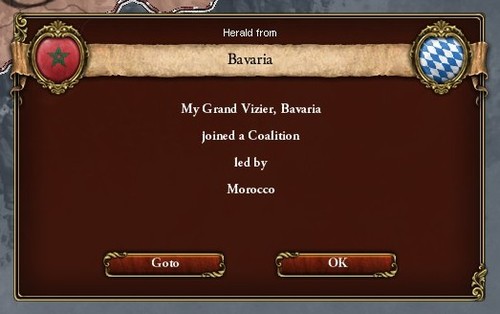

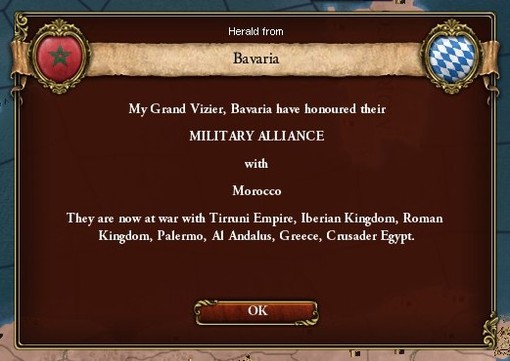

Unfortunately for Tirruni, that would not be the end of his troubles, not by a long shot. Moroccan diplomacy had, for the umpteenth time, convinced the Archduke of Bavaria to rejoin the war. Thus, in a jointly-planned offensive, Bavarian and Hungarian troops poured into northern Italy just before winter arrived.

The smaller Tirruni force, which was now badly outnumbered, could do nothing but watch as vast stretches of the Po Valley fell to the enemy. And with the French invasion in full force further west, Sahim had no spare troops to counter it. He was badly overextended, and unless something was done to relieve his stretched frontlines very soon, it was likely that they’d all simply collapse.

Word of the spiralling war situation reached Qadis before too long, and with the Almoravid Sultan still refusing to entertain any peace talks, Zulfiqar was forced to act.

Embarking on a forced march that would last several long weeks, the Grand Vizier decided to lead his army across Iberia, Occitania and Italy in an attempt to aid his ally - and, more importantly, bring about a quicker end to this destructive war.

Of course, he needed to reach Italy before the entire peninsula fell to the enemy, so the march was harsh and relentless. Soldiers were forced to walk 20 to 30 miles a day, living off the land where they could and rations where they couldn’t, with any stragglers quickly punished or executed for desertion.

He was tough and unyielding, but the army reached Genoa before year’s end, so it was all worth it - at least, as far as Zulfiqar was concerned.

The Grand Vizier wasted no time at all, immediately leaping into action and engaging a 15000-strong Hungarian army besieging Verona. Taken aback by the sudden attack, the Hungarians attempted a hasty retreat, but Zulfiqar managed to pin them down and force a battle a few miles east of the city.

The battle was largely one-sided, and once the 20000-strong Tirruni army reinforced the fighting, it’s result was almost a certainty. Thousands of Hungarians were routed early in the battle, and after surrounding large parts of the enemy force over the next few hours, thousands more were killed or captured in a decisive victory.

Not resting on his laurels, Zulfiqar followed his victory by quickly striking west, and pinning down another Hungarian army near Milano.

And again, with the help of reinforcements, the Andalusi utterly crushed the Hungarian army in a short but bloody battle. The Hungarians suffered over 15000 casualties in just three hours of fighting, and with the vast majority of their army lost, the survivors were forced to flee northward and into Bavaria for refuge.

Zulfiqar was quick to pursue them, marching into the harsh and unforgiving Alps for the first time, only to come across a much larger army. Standing at almost 30000-strong, the Bavarian army had only just crossed the border before meeting a massive Andalusi-Tirruni force, together numbering 90000 soldiers.

Faced with such drastic odds, the Bavarians had no hope of emerging victorious, and suffered heavy casualties before retreating back into friendly territory.

Three months, three battles, three victories. March had arrived, and the entirety of north Italy had been recaptured by allied forces, with the various Hungarian and German armies defeated and repelled. Upon hearing of these successes, Emperor Tirruni quickly began arrangements to meet with Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, so the two leaders could better coordinate their future movements and strategies.

For Zulfiqar, however, his short campaign abroad had come to an end. On the morning of the eighth, messengers from Qadis had arrived in his camps at Milano, carrying news of yet another invasion of al-Andalus.

This must’ve been why the Almoravid Sultan was so resistant to peace negotiations - he wanted one last crack at actually defeating al-Andalus. 40000 Berbers thus landed a few miles north of Qartayannat, quickly marching south and laying siege to the city, likely hoping to capture it and push into Iberia before Zulfiqar could arrive.

The Grand Vizier thus abandoned any further offensives in north Italy, quickly pushing his army on a forced march back to Iberia. Just in case he didn’t make it back in time, however, he also sent messengers ahead of his army, instructing the Majlis al-Shura to take out several large loans and begin recruitment programs.

And as the Andalusi army made its way back to Iberia, word reached the Grand Vizier of French troops pillaging and burning their way across Occitania. Vastly outnumbering Tirruni, they had managed to defeat the Emperor in a series of pitched battles, allowing them to push all the way to the Alps before being forced to a standstill.

At the same time, an ambitious general had landed a small Moroccan force off the coast of Naples, quickly darting inland and capturing the city after a short assault. The general then pushed northwards, seizing Gaeta and marching on Rome itself, eager to shower himself with glory by conquering the holiest city in Christendom.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Mediterranean, Zulfiqar and his army had just arrived in al-Andalus. Fortunately, Qartayannat had not fallen to the enemy just yet, with its reinforced walls resisting the Moroccan assault for an impressive three months.

Even better, the first of the newly-raised recruits also began arriving in army depots all across al-Andalus. There wouldn’t be enough time to properly train them, so Zulfiqar gave the order to formally induct them into the military, and the conscripts began rallying at Batalyaws instead.

The Grand Vizier quickly pushed south towards Batalyaws, and upon reaching the populous city, he began planning for his engagement with the invading Berbers. He consolidated his armies, creating a single larger force, and shuffled his commanders slightly so that the older and more experienced Uthman al-Houd, Cyrah ibn Cyrah and Ibn Bibil were all serving under him.

Once his army was ready, Zulfiqar began the march east, towards Qartayannat and the Berbers. Just days before reaching the city, however, an assault was launched through a small breach in the walls - and after four bloody hours, Qartayannat fell to the Berber army.

The Berbers didn’t sack the city, however. In fact, they installed a small garrison and promptly left, pushing northwards on a forced march towards Qattalun.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, determined to send a message, pursued the Berber army all the same. A short chase into Qattalun followed, a chase that ended with the Berbers being pinned down at Balansiyyah, a city dominated by Andalusi. The numbers were roughly equivalent, so this battle would come down to tactics and sheer willpower, with the Andalusi bent on quashing the Moroccan invasion.

Despite being so far from home, the Berbers put up a decent fight, forcing a stalemate for several hours early in the battle. The momentum quickly shifted, however, when Raed Zulfiqar executed a stunning manoeuvre that isolated the Moroccan flanks from their centre, allowing the Andalusi to quickly surround and crush large parts of the Berber army with relative ease.

Zulfiqar had been the Grand Vizier of al-Andalus for decades now, he was old and tired and ready to retire, but on that day he proved his brilliance on the battlefield yet again. Out of 60000 at the outset of the day, scarcely 12000 Berbers had survived to see the sunset, with the rest all rotting under the soil or rotting in chains - either way, the Andalusi ended the battle in a decisive victory.

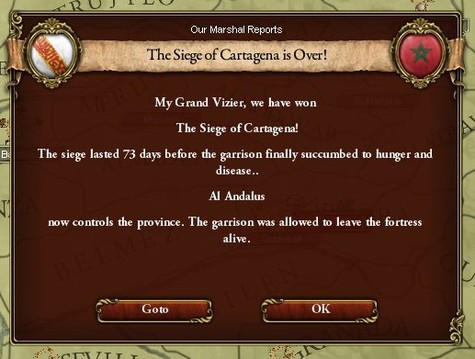

And after crushing the remnants of the army, the Andalusi pushed south and besieged Qartayannat, which in all likelihood would fall within a few weeks. And then, Zulfiqar was certain, the Almoravids would be more open to peace.

Further north, meanwhile, the French advance across Occitania continued. Sahim Tirruni seemed to have met his match, because the French crushed his armies in several engagements across Aquitaine and Provence, and it was becoming increasingly difficult for the Emperor to raise new armies with his already-exhausted manpower reserves.

January of 1835 saw the Almoravids land another blow on Tirruni, as the Berber army - which had now been reinforced with another 15000 troops - captured and plundered Rome. And in typical Almoravid fashion, the holy city’s most valuable artefacts were quickly sent to Marrakesh, where they would decorate the vast and pristine Hall of Relics, newly-built after the Andalusi had burned the old hall to cinders.

In north Italy, meanwhile, the situation had quickly deteriorated after Zulfiqar had left. March saw the beginning of a combined Hanoverian-Hungarian offensive into the Po Valley, with vast stretches of land falling to the invaders over the course of April and May.

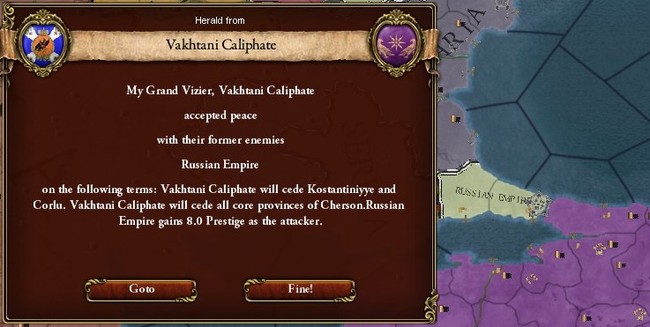

The early days of 1835 also saw the declaration of a new peace treaty between the Russian Empire and the Vakhtani Caliphate, with the latter forced to cede the largely-ruined and depopulated city of Constantinople, guaranteeing Russian access through the Bosphorus and into the Mediterranean. Empress Dobroslava announced her intention to rebuild and revive Constantinople, with a steady influx of ethnic Russians being resettled in the historic city before long.

More importantly, peace on one front allowed the Russians to shift their resources westward, with a new offensive into Italy launched before the end of the month.

Occitania and Italy were now all but lost to the enemy, with Sahim Tirruni forced to retreat to Qattalun, where he had built the beginnings of his empire all those years ago. Now, this would be where he’d make his last stand. This would be his last battlefield.

As for Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, such claims to glory were not really his wheelhouse, and he was becoming increasingly desperate to end the war before it could reach al-Andalus. So when Qartayannat finally fell to his army in June, he wasted no time in dispatching diplomats to Fes.

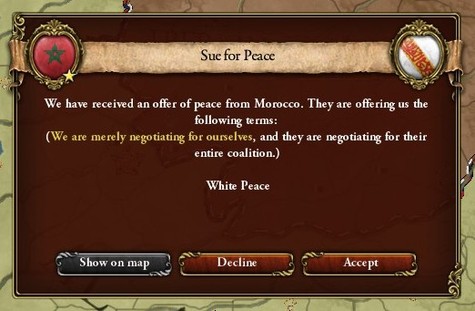

And indeed, after seeing another invasion of Iberia foiled, Sultan Yahya was just as desperate for peace as Zulfiqar. He agreed to a status quo of borders, whereby al-Andalus would retain all of its core possessions and captured territories, at least until a conference of great powers could be called.

And with that, after fifteen years of constant warfare, peace finally returns to al-Andalus.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar is an ambitious man, however. More importantly, he is patient and astute, all too happy to wait until the balance of power shifts in favour of him and his nation. And as the sweltering summer of 1835 hits Iberia in full force, the Grand Vizier’s eyes drift to the vast, rich and sparsely-defended lands of the north…