Part 74: Last Days of War – 1836

Chapter 10 - Last Days of War - January 1835 to January 18361836 would mark the end of an era. An era that lasted only fifteen years, admittedly, but these fifteen years would live on for much longer in the minds of the victors. It had been fifteen years of loss and devastation for some of the world’s greatest powers. Fifteen years of death and carnage, with the blood of millions watering the fields of Europe, North Africa and the Near East. Fifteen years of war on an unprecedented scale, with the ruinous conflict stretching from Safi to Moscow at its height.

And now, at long last, the end was in sight.

The countdown was already on, with rumours quickly spreading of the Almoravid Sultan organising meetings with the other great powers, drafting plans for a post-war Europe. For Al Andalus, who had fought against the Berbers for the majority of the wars, this was not a good thing. They needed some weight in the negotiations, they needed leverage of their own, a guarantee that the other great powers wouldn’t play them fools.

And the Grand Vizier of al-Andalus, Raed Zulfiqar, knew exactly how to do that.

From the very moment of its creation, Zulfiqar had been vehemently opposed to the so-called Iberian Kingdom - a puppet state set up by Tirruni, who obviously hoped to eventually bring all of Iberia under his rule. Now, however, the Grand Vizier finally had the chance to tear it down, and gain some much-needed goodwill with the other powers of Europe at the same time.

Al Andalus formally declared war on the Iberian Kingdom early in the new year, with Sahim Tirruni quickly flocking to the defense of his puppet, which was led by his own son - Qays Tirruni, a cruel and brutish ruler.

Zulfiqar, who was personally leading the Andalusi army, opted to strike hard and fast. He quickly crossed the border and marched on Majrit, laying siege to the city before the month was out.

With that, Tirruni was hit with what would surely be the final nail in his coffin. For all his genius on the battlefield, the Emperor had been played like a fiddle in the game of diplomacy, with the Almoravids slowly building a coalition that stretched from the Atlas to the Ural mountains - all opposed to Sahim Tirruni.

And as the first morning of 1836 dawned, the Emperor found himself surrounded by enemies on every side, with the assorted armies of France-England, Hannover, Bavaria, Hungary, Russia, Bulgaria and Morocco all marching against him.

The Dual Monarchy of France-England had invaded Occitania a few months past, forcing Tirruni to march the majority of his armies westward, leaving his territories in northern Italy sparsely defended. The Germans and Hungarians were thus able to push into the peninsula at speed, besieging and capturing Venice, Mantua and Parma before finally being forced to a halt.

With the aid of fresh recruits, Tirruni was able to launch a decisive counterattack, pushing the coalition forces as far back as the Alps. Unfortunately, however, this was when the Russians chose to rejoin the fray.

100,000 soldiers poured across the border early in February, quickly wiping out the Iberian army stationed at Lienz, before assaulting and capturing the fortress.

The army then launched a wide-front invasion into the Italian peninsula, quickly followed by another 130,000 Russians. Tirruni had no chance of prevailing against such numbers, and was forced to retreat into Occitania, surrendering north Italy to the Russians.

Back in Iberia, the Andalusi managed to capture Majrit after two months of siege, breaching and seizing the city in a bloody assault.

Once a new garrison was installed, Zulfiqar led his army further north, only to be met by a 35000-strong army, sent by Tirruni to repel the Andalusi. The Grand Vizier was forced to retreat into friendly territory, before launching a counterattack and engaging the army at Talavera, armed with numerical and tactical superiority.

And within a few hours of fighting, it became clear that the enemy was outclassed, with Zulfiqar expertly isolating and crushing the enemy flanks before converging on the centre. When the enemy army finally fell back, retreating in chaos and disarray, they left behind almost 30000 dead and captured comrades.

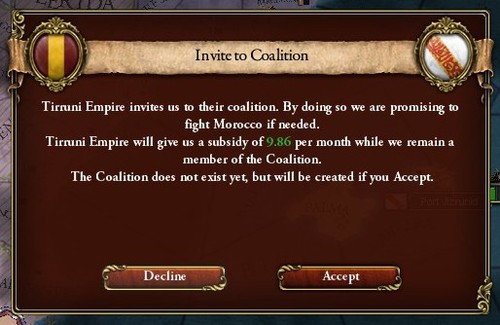

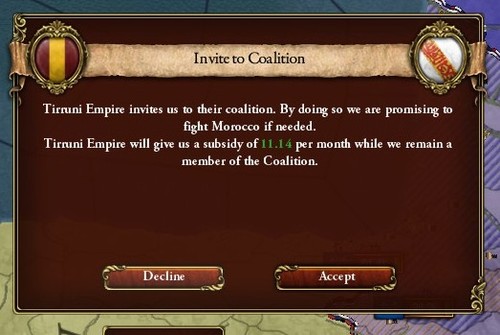

Word of the victorious battle quickly spread throughout Iberia, and from there to the rest of Europe. Congratulations arrived from other European powers before long, with both France and Russia even pledging to supply the Andalusi with subsidies, on the condition that they continued to weaken Tirruni on the southern front.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, of course, was happy to comply. He quickly invested this new income into raising new armies, instructing his subordinates to begin the recruitment and training of fresh troops.

Over the next month, the Grand Vizier masterminded a series of campaigns deep into the Iberian Kingdom, with his forces besieging and capturing dozens of towns, cities and fortresses throughout March and April. More importantly, these months saw al-Hejarah and Salamanqah capitulate to the Andalusi, both of which were well-populated and strategically-important cities.

With the southern half of the Iberian Kingdom now under his firm control, Zulfiqar felt confident enough to march on Burghus, the capital and largest city of the puppet state. 50,000 Andalusi thus lay siege to the city before the end of April, with ear-splitting gunfire reducing its outer walls to rubble within days.

Burghus was large and well-fortified, however, and its defenders largely consisted of the notoriously-resilient Castilians, so it would be no easy task to capture Burghus. The next few weeks were thus comprised of a slow, protracted advance into the city, with the Andalusi paying a costly price in blood and lives for every step they took.

Just before summer arrived, however, the city finally fell to its besiegers. The Grand Vizier made sure that Burghus was not sacked or plundered, however, loudly proclaiming that it was an Andalusi city - and would be treated as such.

Once an Andalusi garrison was installed in the city, Zulfiqar launched on another offensive northward. Before he could push much further than Soria, however, his scouts sighted the vanguard of another Tirruni army nearby. The Grand Vizier quickly marched to meet the enemy, determined to seize another decisive victory against Tirruni, and hopefully end any threat to his captured territories with it.

The enemy commanders were caught off-guard, it would seem, with their ranks quickly dissolving into chaos after being engaged by the Andalusi. They were forced to fall back within hours, but Zulfiqar pursued the fleeing army a few miles west and crushed them again, this time surrounding and annihilating the entirety of the army.

The battle ultimately prove to be a pyrrhic victory for the Andalusi, however, with casualties running high on both sides. With his army now numbering just 15000, Zulfiqar was forced to postpone any further offensives and retreat to friendly territory, where he could reinforce his ranks. And fortunately, this was exactly when the first of the new recruits began arriving, quickly given their uniforms and guns upon arrival.

So within a few weeks, the Andalusi had regained enough strength to begin operations again, with Zulfiqar sending the army to besiege Liyun. Liyun was one of the largest and richest cities in northern Iberia, but it had none of the extensive fortifications that had allowed Burghus to hold out for so long, and was forced to surrender to the Andalusi after just a month of siege

With the fall of Liyun, the only parts of the Iberian Kingdom still standing free was the northern coast, a mountainous region known as Qantabriyya. Eager to bring an end to this conflict, Zulfiqar wasted no time in marching into Qantabriyya, besieging its major regional cities within the week.

And with no hope of relief forces arriving, these sparsely-defended cities couldn’t hold out for very long. Ma’dam Shamal fell after a month-long siege, quickly followed by the fortresses dotting Bisqaya and Banbaluna.

With that, just as the sweltering summer of 1835 peaked, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar brought entirety of the so-called Iberian Kingdom under his control.

He wouldn’t have much time to bask in his achievement, however, with a 40000-strong army arriving in July to complicate matters. After his two previous expeditions had met with resounding failure, Sahim Tirruni decided to personally lead a newly-raised army into Iberia, determined to crush Zulfiqar once and for all.

And Zulfiqar wasn’t about to surrender all of his territorial gains at the mere sight of Tirruni, so he stood his ground and met the advancing army, with 85000 soldiers clashing in what would later be called the Battle for Iberia, for obvious reasons.

From the very outset of the battle, it was clear that Zulfiqar was facing a beast unlike any other. Sahim Tirruni knew how to exploit and counter every trick in the book, his ability to inspire his men was unmatched, and his very presence on the battlefield was a force to behold. Needless to say, the conqueror’s reputation was well-earned.

Zulfiqar was no rookie, however, and he was able to repel Tirruni’s assaults and manoeuvres with interest. Even so, he suffered heavy casualties in the early hours of the fighting, with the battle only balancing out after the Grand Vizier began launching counterattacks of his own. After half a day of heavy fighting, both sides were exhausted and spent - but it was Sahim Tirruni who was forced to retreat, effectively abandoning the Iberian Kingdom by falling back into Qattalun.

That very night, half of Iberia erupted into raucous celebrations as word of the victory spread. A battlefield victory against Tirruni himself was no mean feat, and congratulatory messages from other rulers and politicians began arriving within days, with the Grand Vizier personally meeting with many of these diplomats - likely in an effort to build friendly ties.

In fact, the aftermath of the battle also saw the Moroccans send an embassy to Qadis, marking the first non-hostile action between the two powers for almost two decades.

Zulfiqar himself was forced to retreat into Burghus, where he and his army could rest and recuperate. The battle had cost him 20000 soldiers, but reinforcements continued arriving over the next few weeks, strengthening his ranks with fresh bodies. By August on 1836, the Andalusi had recovered enough for the Grand Vizier to launch on a new offensive - this time into the Tirruni Empire itself.

Zulfiqar met with little resistance as he pushed into Qattalun, with Sahim Tirruni apparently retreating all the way to Narbuna, where a French army had besieged his capital. The 40000-strong Andalusi army was thus free to lay siege to Saraqusta, with the massive city surrounded and subjected to heavy artillery fire within hours.

Further north, Tirruni had managed to lift the siege of Narbuna, crushing the French armies in a series of battles around the capital. He followed this up by pushing further north, recapturing several important cities in a sudden counterattack, before finally being forced to a standstill at Cahors.

In the east, meanwhile, northern Italy had been ravaged by a conglomerate of Germans, Hungarians and Russians, who were now pouring into Provence.

As for Central Italy, Hafid Tirruni - Sahim’s eldest son and heir - had managed to recapture dozens of cities and fortresses dotting the Roman Kingdom, calling on the Italians to unite and repel the invaders. Unless he received serious reinforcements from his father, however, the entirety of the peninsula would be lost before very long.

Tirruni suffered another blow late in September, as the city of Saraqusta succumbed to an Andalusi assault, though at the cost of thousands of casualties.

Any number of deaths would’ve been worth it, however, because the fall of Saraqusta paved the road towards Barshaluna and Narbuna. So after a short respite, Zulfiqar led another offensive deeper into the Tirruni Empire, sweeping across the depressed plains and towards the coast of Mediterranean.

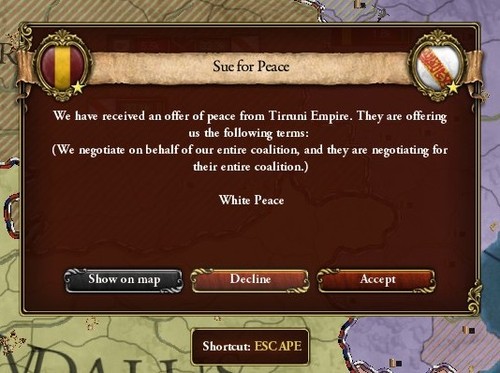

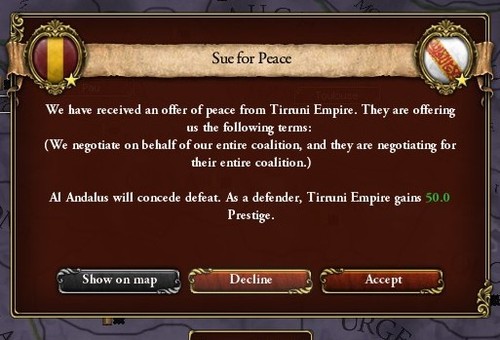

This was when Sahim Tirruni, finally realising that the advance of the Andalusi couldn’t be halted, began making overtures for peace. The negotiations that followed proved him to be a stubborn and pigheaded man, however, with the Emperor refusing to make any concessions to the Andalusi. Instead, he demanded that they pull back and abandon all captured territories, or else suffer his wrath.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar brought the negotiations to a quick end after that, of course. If Tirruni wasn’t willing to bend, then he would break, and Zulfiqar had no problem being the hand that shattered the emperor.

Tarrakunah was amongst the largest cities in Qattalun, but it also stood as a barrier to Zulfiqar’s advance, so the Grand Vizier wasted no time in ordering an assault on the city. Andalusi artillery breached its walls within days, with thousands forcing their way into the city over the next few weeks, slowly fighting their way towards the citadel.

After 40 days of guerrilla fighting and street battles, the governor of Tarrakunah finally capitulated, laying down his arms and surrendering to Zulfiqar.

Once the soldiery were rounded up and imprisoned, the city was quickly pacified, with Zulfiqar ready to embark again within weeks. September thus saw the Andalusi army leave Tarrakunah and push northwards, marching on Barshaluna, one of the most densely-populated and richest cities in Iberia.

For all its treasures, however, Barshaluna represented something far greater than loot or plunder. If Barshaluna fell, then the de facto borders of al-Andalus would extend over the entirety of Iberia for the first time in centuries, for however short it may last.

Zulfiqar thus went into the siege of Barshaluna with a determination and zest he’d never displayed before. The city had been well-fortified by Tirruni in recent years, with the surrounding ditches greatly expanded, small fortresses constructed around the city, and new parapets erected for mounted artillery.

And for the next two months, the defenders gave as good as they got, with deafening gunfire and explosive shells being traded in a bloody stalemate. No relief forces arrived to lift the siege, however, and October saw the Andalusi force several breaches in the city’s walls, allowing them to batter the city centre with heavy gunfire. With the casualty count running high and the population’s morale depleted, the city governor was finally prompted to capitulate, surrendering Barshaluna to Zulfiqar.

With that, almost all of Iberia came under the control of Zulfiqar and al-Andalus, with the notable exception of Qartayannat and Narbuna. Sahim Tirruni had no time to retaliate, however, with the Emperor personally leading counterattacks into Occitania and forcing the French backwards, even as the Russians and Germans advanced from the east.

And with Tirruni distracted, Grand Vizier Zulfiqar was confident enough to launch one final offensive - straight towards Narbuna, the heart of the Tirruni Empire.

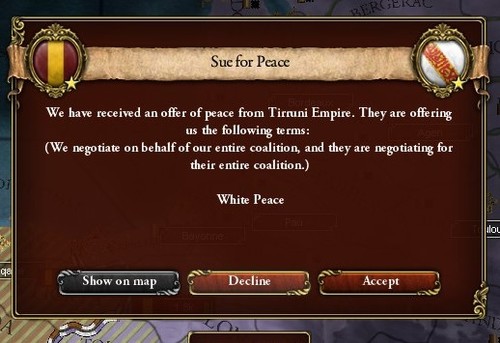

The Andalusi army thus pushed northwards just as October came to an end, but Zulfiqar achieved his objective before even reaching the city, with a desperate Sahim Tirruni finally agreeing to make peace on Andalusi terms.

Eager to make the negotiations quick and conclusive, Zulfiqar’s terms were short and simple: that the unlawful Iberian Kingdom finally be dismantled, and its territories ceded to Al Andalus.

And this time, Tirruni had no choice but to concede defeat, agreeing to all of Zulfiqar’s demands. In return for withdrawing from Qattalun, the Emperor agreed to relinquish his supremacy over the Iberian Kingdom, ceding all of his territories west of Saraqusta to the Andalusi.

And with that, at long last, the last days of war come to an end. Al Andalus now stretches from Qadis to Qantabriyya, and even with Qattalun still beyond its grasp, the past fifteen years have seen the Andalusi rise to become the dominating power in Iberia once again.

Now, Zulfiqar can sit back and begin working in the shadows, slowly increasing relations and building closer ties with the great powers of Europe.

As for Tirruni, the withdrawal of the Andalusi from Qattalun didn’t really help that much, with one problem quickly being replaced by another. November saw the beginning of another massive invasion of the Tirruni Empire, with 90000 Berbers pushing northwards and into Qattalun, crushing everything in their path.

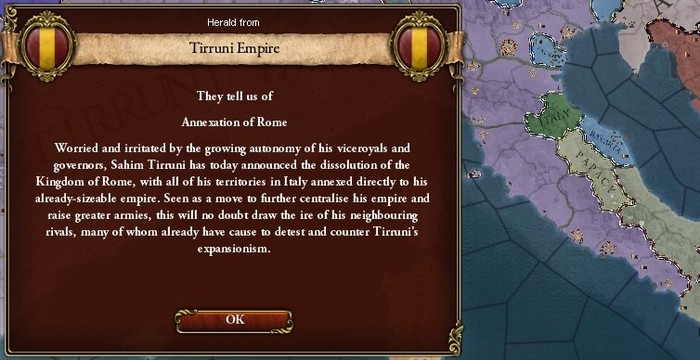

Tirruni had literally no manpower reserves to counter this invasion, however. So in an attempt to free up more resources, he proclaimed the annexation of the Kingdom of Rome, quickly sending troops to assert direct rule over Central Italy.

This attempt to raise more soldiers would prove futile, however, as the Russians and Germans simply pushed south on a renewed offensive, besieging and capturing Rome after a short, bloodless siege.

Across the Adriatic Sea, meanwhile, the Serbian Republic stood in a striking parallel to the Tirruni Empire. The Republic had been at odds with their neighbours since its very inception, but the recent succession of corrupt and inept leaders had seen the fortunes of the Serbs quickly decline, with the once-renowned Revolutionary Armies now unable to defeat even the tiny Greek forces.

The dying days of 1835 thus saw the Serbian Republic quickly collapse to a variety of invaders, with the Greeks and Berbers pushing up from the south, the Bulgarians from the east, and the Hungarians from the north. The Balkan Crisis was quickly reaching boiling point, attracting the attention of the surrounding great powers, who saw it as a danger to the already-precarious balance of power.

Further east, the old and decadent dynasties ruling Egypt and Armenia continued their struggle for dominance in the Near East, with the decade-long war for the Levant showing no signs of slowing down. December of 1835 would see Almoravid emissaries arrive at both Alexandria and Erzurum, however, inviting the two powers to make peace at an international conference of great powers.

At the same time, the Berbers and French continued their offensives into the Tirruni Empire, with the two armies meeting at the Pyrenees. Almost the entirety of Qattalun had fallen to the Almoravids over the course of November, and on the first brisk morning of December, the Berbers began their march on Narbuna.

Emperor Tirruni, despairing and facing hopeless odds, reached out to the Majlis al-Shura just the Berbers began their offensive. The Andalusi had a long history of repelling Berber invasions, so Sahim Tirruni offered them rich concessions in gold and territory in return for assistance, practically begging for help.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar had no use for promises, however, not when the odds were stacked so highly against him.

With his manpower reserves exhausted, his treasury bare and his troops near-mutinous, Sahim Tirruni was on his last legs. The Hungarians had seized Rome, the Germans and Russians had captured large parts of north Italy and Provence, the French had descended on Occitania, and the Berbers had overrun Qattalun.

All that Tirruni had left was some 30,000 loyal soldiers, and his capital.

And slowly but surely, the Berbers and French advanced from the south and north, surrounding the Emperor on two sides. Tirruni focused his troops on the northern threat first, somehow outmanoeuvring and defeating the French armies in a series of dazzling victories, before darting south to confront the Berbers.

Just before he could intercept them, however, the Berbers managed to breach the already-damaged walls of Barshaluna. Quickly capturing and pacifying the city, the Berber army pushed northward on an offensive of their own, meeting Sahim Tirruni below the walls of Narbuna.

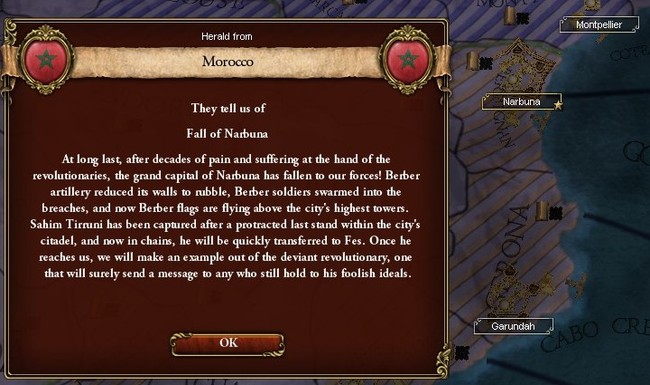

And there, the final battle of the Tirruni Wars was fought. Three hours of thick, bloody fighting saw the balance shift countless times, but it was the Berbers who emerged triumphant in the end, forcing Emperor Tirruni to retreat into his capital with the remnants of his army. He would find no relief there, however, as Narbuna was quickly surrounded on land and blockaded by sea.

Even then, he began making preparations for a lengthy siege, stockpiling food and refortifying the walls. Sahim Tirruni would fight until the very end, that much was clear.

His officers, however, were not so willing to forsake their lives. Negotiating a secret armistice with the Moroccans, they opened the gates and surrendered the city to the Berbers, who quickly marched on Tirruni’s palaces. There, the Emperor was surrounded and forced into chains after a futile last stand, before being forced onto a ship. Orders were to escort Tirruni to Fes, where he would meet with the Almoravid Sultan before having his fate decided.

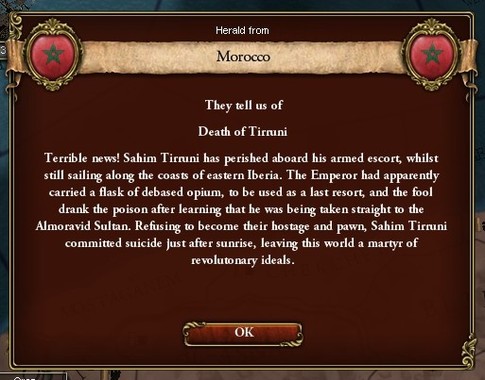

Tirruni would be no man’s pawn, however.

Whilst the heavily-guarded escort ship was sailing along the coast of Balansiyyah, Sahim Tirruni drank from a small flask he always carried around his neck, a flask containing debased opium. Swallowing several drafts of the poison before collapsing to floor of his cell, the self-made emperor uttered his final words to his captors: “My final victory.”

When Tirruni’s body docked at Algier, word of his death quickly spread across north Africa and Europe. At Fes, Sultan Yahya was said to have gone into a great rage upon receiving the news. At Qadis, it was met with mixed feelings, with some rejoicing and others mournful. At Narbuna, it incited the outbreak of massive riots, with dozens of Berber soldiers killed before the rioters were pacified. And in Paris, Hannover and Smolensk, the news was met with celebration and revelry, as it finally marked the end of the great war.

And indeed, as the first days of 1836 dawn, the Tirruni Wars come to their inevitable end. The past fifteen years have seen alliances forged and broken, they’ve seen battles fought and lives lost, they’ve seen new nations rise and old powers collapse, they’ve seen emperors crowned and emperors vanquished.

As with any conflict, however, only one side can emerge victorious - and the monarchist bloc does just that, led by the Almoravids of Morocco. The ideals of the revolution have been crushed, absolutism has been reinforced, and the future of Europe now hangs in doubt.

———

Raed Zulfiqar was old and tired.

At almost 70 years of age, he had led the Majlis-al-Shura for the past 15 years, ruling with absolute power as the Grand Vizier. He had conducted the invasion of the Mahdiyyah and the capture of Qurtubah, which precipitated the revival of al-Andalus. He had overseen the expedition to Morocco, a campaign that culminated in the sack of Marrakesh. He had personally led the invasion of the Tirruni Empire, defeating Sahim Tirruni and seizing northern Iberia for al-Andalus.

Yes, he had accomplished a great deal, and he was ready to retire. There was one last thing to do before then, however, one last hurdle to overcome…

The Congress of Cádiz, it was already being called. The Tirruni Wars had proven to be more destructive and devastating than any previous conflict, and for good reason - it had bankrupted most of the great powers, it had left vast swathes of Italy and North Africa depopulated, and it had incited the outbreak of dangerous revolutionary wars all across Gharbia. Was this the price of victory?

So in an effort to prevent such ruinous wars in the future, the great powers have agreed to meet at a grand conference in Qadis, where they will discuss the partition of the Tirruni Empire and the balance of power that it will establish. Morocco and Russia were the founding members of the congress, quickly joined by Hannover, Bavaria, Hungary and Al Andalus. France-England, Armenia and Egypt were all strong-armed into ending their wars and joining the conference, or else face a combined coalition of the congress powers.

Grand Vizier Zulfiqar, who’d convinced the leading powers to stage the congress in Qadis, knows full well that the next few months are going to be very dangerous. The congress promises to reshape Europe and the Near East in the interest of long-term peace, but rivalries runs deep between its members, and few believe that these foes can set aside their hatred so easily.

Whatever the outcome, the Congress of Cádiz is sure to establish a new balance of power, and with it a new era begins. The next hundred years will bear witness to the spread of liberal and nationalist movements, it will see the rise of industry and manufacturing all across the world, it will fuel rapid developments in science and medicine, and it will herald the dawn of new imperialism. Groundbreaking inventions will take hold, culture and technology will advance at an unprecedented scale, and nation-states will rise and fall at the whim of the wind. There’s no doubt about it, a new era is certainly beginning.

The only question that remains, is whether al-Andalus is ready to meet it?