Part 87: Red Banners

Chapter 7 - Red Banners - 1862 to 1865North Germany had been in constant turmoil and mayhem for almost two decades by 1860, having suffered devastating back-to-back losses to neighbouring great powers, stunning neutral observers and military experts alike. The subsequent collapse in hierarchy and order led to the radicalisation of countless Germans, who began agitating for radical ideals and an end to monarchy altogether, but these Radical Liberals weren’t the only breed of revolutionary to be borne from all this chaos.

A new movement had been gradually gaining traction these past few years, with its leaders calling for a ‘Great Levelling’ in which any distinction between owner and worker would be utterly demolished, and leaders were elected based on individual merit instead. These ‘socialists’ were quickly met with hostility from German authorities, who prohibited their gatherings, outlawed their newspapers and violently crushed any protests.

Socialism would not die so easily, however, with the brutality and violence only further radicalising its proponents. From Berlin to Hanover, red banners were raised high in defiance of the authorities, drenched in cow’s blood to symbolise the suffering of the working class.

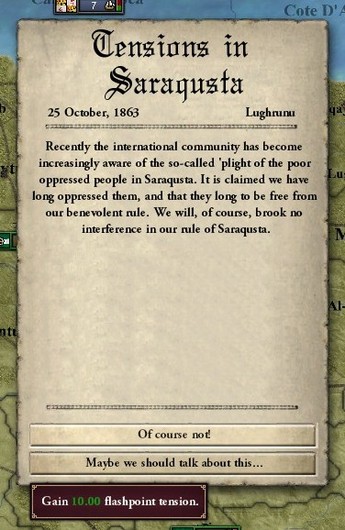

And their ideals would resonate with workers and labourers all across Europe, as a series of socialist publications and editorials quickly spread across the continent, eventually reaching Al Andalus late in 1862, prompting the ruling nobles passed a string of anti-socialist laws, banning the spread of the socialist creed in any form whatsoever.

These laws would only further aggravate existing tensions, however, especially in poor, rural regions of northern Iberia, where riots and mass brawls became commonplace.

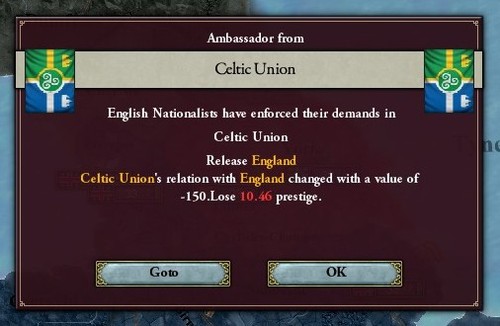

To the north, the Celtic Union were also suffering the woes of nationalism, as a spontaneous uprising led to the declaration of the "Republic of York". And they could do nothing to retaliate, as Celtic armies and manpower were largely destroyed by their recent wars, with the prime minister reduced to belligerent insults and bloodthirsty promises.

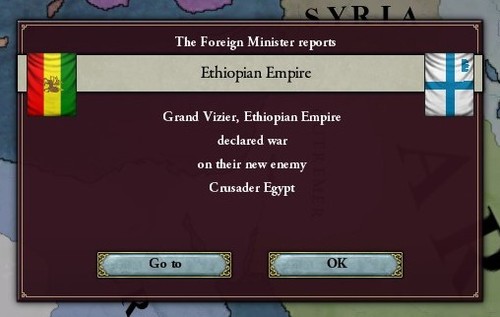

To the east, meanwhile, another war erupted between the Ethiopian Empire and Crusader Egypt. The Ethiopians invaded Sudan with a huge army, consisting of the combined forces of themselves, Assab, Harar and Ajuuran - but once again, they met with stinging defeat at the hand of the Egyptian army, who counterattacked into Ethiopia, seizing control of Begemder and Amhara.

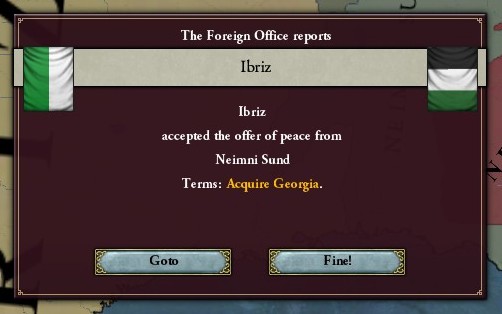

And across the width of the Atlantic Ocean, the Revolutionary Republic of Ibriz had just concluded their first offensive war in decades, effortlessly crushing the badly-trained, under-supplied armies of Neimni Sund. The ensuing peace treaty saw Ibriz establish a new eastern border along the banks of the Mississippi River, a natural barricade essential to the defense of the republic.

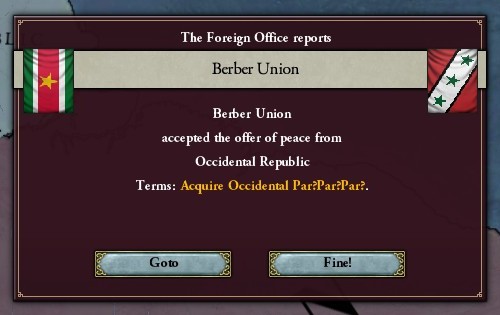

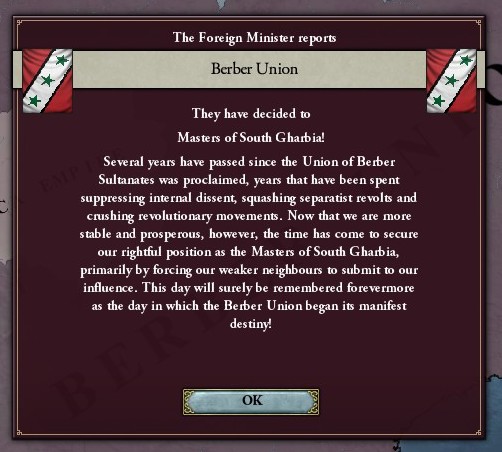

Pushing southwards, the Berber Union had also ended their war with the Occidental Republic, quickly storming across the country and crushing any resistance. And once peace was declared, the Three Sultans met in Imariz to proclaim the end of their ‘submission campaigns’, with their Union of Berber Sultanates emerging as the sole and uncontested dominant power of South Gharbia.

Back in Europe, meanwhile, Andalusi diplomats scored a long-awaited, much-needed victory. When the Dual Monarchy had traitorously broken their alliance with Al Andalus, they had been left surrounded by the two strongest powers in the world, and nobody of any note backing them up. Al Andalus was, to put it simply, a sitting duck.

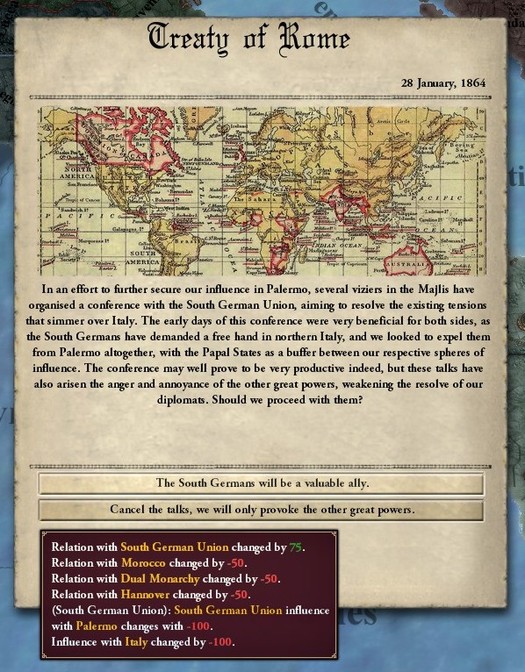

So Grand Vizier Musad had quickly dispatched several Andalusi diplomats to München, where a defensive alliance was drawn up between the two powers.

This alliance did not come without compromise, however. The South Germans were annoyed by the recent Andalusi meddling in Palermo, so several viziers were sent to Rome to meet with German diplomats, in an attempt to resolve the tensions simmering over the peninsula.

And after two months of debate and conciliation, a settlement was finally reached: Al Andalus would withdraw their ambassadors from the Italian Republic, and the South German Union would do the same in Palermo, with the Papal States serving as a neutral buffer between their respective spheres of influence.

The Majlis thus dispatched a small army to impose their dominance in Palermo, whilst the South German Union acted quickly to incorporate Italy into their sphere of influence, allying and guaranteeing their southern neighbour. The French retaliated by stationing forces in Turin, ready to rush towards Rome or Venice at the first sight of war.

And with that, the state of affairs in the Italian peninsula becomes ever more tense, with the French asserting their influence in the west, the Germans in the east and the Andalusi in the south.

And it didn’t stop there. The Archduke of Bavaria also had envoys and emissaries in the north, where they were carefully promoting closer co-operation between the South German Union and north German minors. And late in 1863, they landed a huge victory when the various counts and princes of northern Germany expelled ambassadors from Hannover, accepting military and economic assistance from South Germany instead.

In Al Andalus, meanwhile, Grand Vizier Musad had been trying - and failing - to deescalate the rising tensions across Iberia

A reactionary movement was gaining strength across the peninsula, numbering over almost two million persons, largely drawn from the Andalusi heartland. These reactionaries demanded a return to absolute monarchy, with powers stripped from the Majlis and granted to the Sultan, as it had been in the earliest days of Al Andalus.

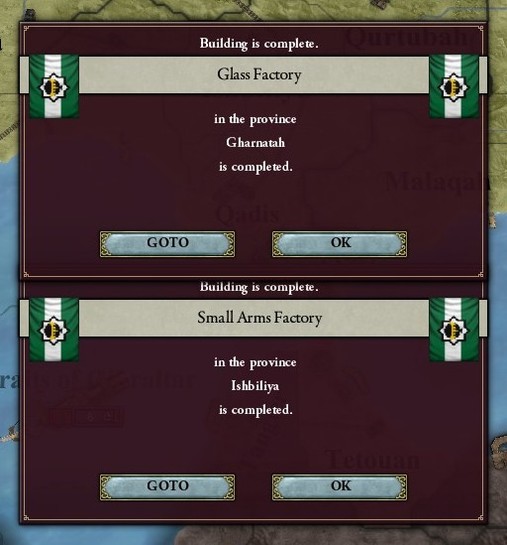

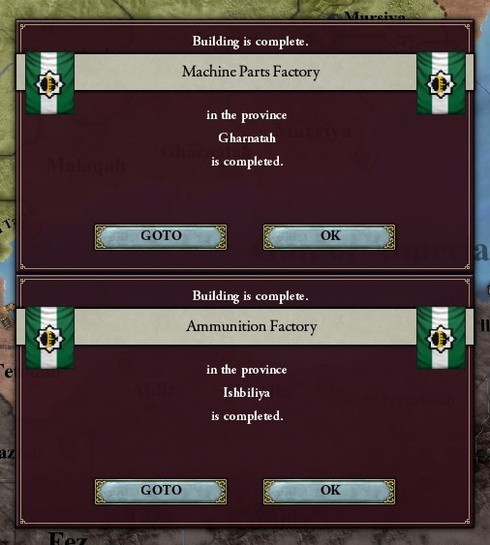

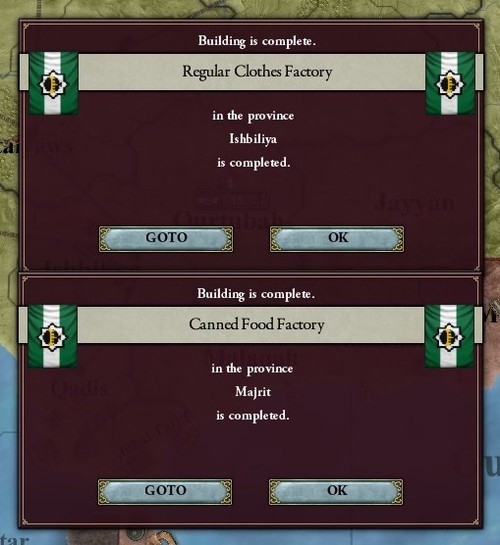

Whilst turmoil and agitation began gaining steam, the richest rungs of society were busy further enriching themselves, with the capitalist class growing in number and strength. Hated by the traditional merchants and artisans of Iberia, these capitalists were slowly becoming the driving force behind the industrialisation of Al Andalus, funding the construction of new manufactories all across the peninsula.

And they were no idiots, largely focusing on establishing ammunition and arms factories, making them an indispensable boon to the Andalusi Army - and thus the Majlis, quickly attracting the support and patronage of countless aristocrats in the assembly.

Before long, the minority parties in the Majlis (especially the moderates) began working with the capitalists to launch new projects, including railroad networks linking the poor, unindustrialised cities of northern Iberia and Qattalun.

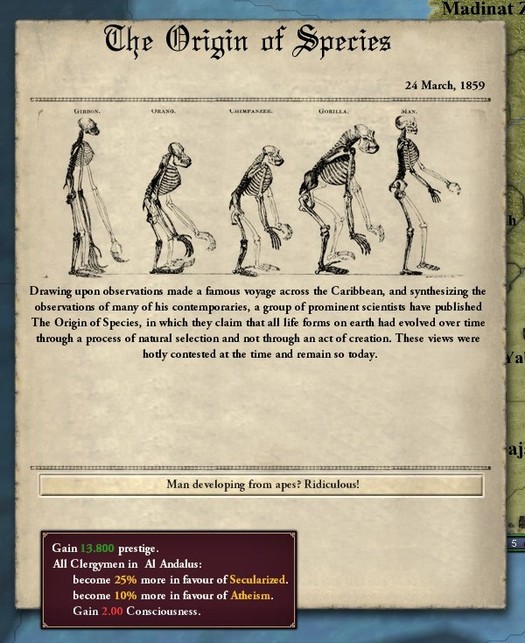

The moderates had also launched several small-scale projects abroad, funding the journey of several prominent geologists, naturalists and biologists across the Atlantic Ocean, where they conducted geographical surveys, logged their investigations, and published unique observations - all of which would come together to build upon the framework of natural selection, a revolutionary evolutionary theory first published in Andalusi newspapers.

Unfortunately, the steady stream of developments from the west would abruptly end late in 1864, as the expedition went quiet. Subsequent search efforts would quickly unearth the grisly truth - that a violent storm had run the ship into a spit of land just off the Leeward Antilles, where every person aboard was eaten by native cannibals. Their bones would return to Al Andalus a few months later, where their state funeral was attended by hundreds of friends, scientists and viziers.

To the north, meanwhile, the Celtic Union finally managed to raise an army against the Yorkist Republic. The Irish marched on York in the winter of 1864, and though the walls of the city were reduced to rubble within days, the English somehow dragged the siege out for several weeks after that, fighting bloody street battles and conducting devastating guerrilla campaigns.

Their strategy wasn’t an indefinite solution, however, and the rebels were eventually overwhelmed. Their elected president was imprisoned, the parliament was burned to the ground, and Celtic flags were hoisted over York once more.

The Dual Monarchy, meanwhile, was fighting wars halfway across the globe. With military and geographic guidance from the Moroccans, the French had been embroiled in their first colonialist war in the Far East, seizing the southern coast of Indochina in a short but decisive war.

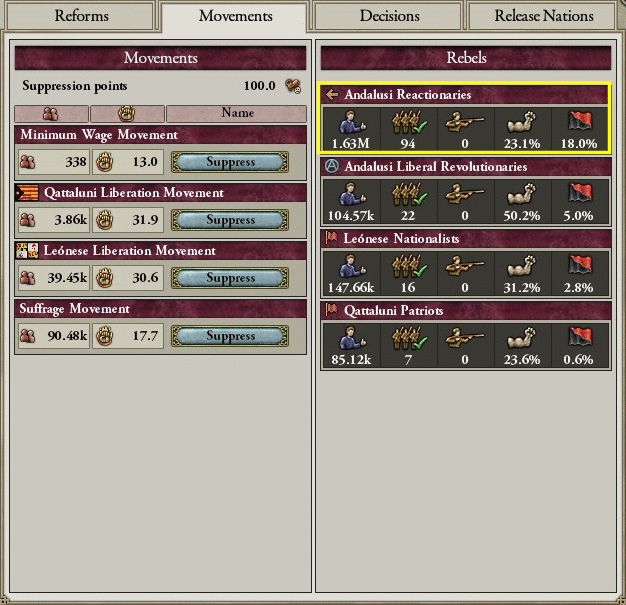

Worrying developments, but the aristocrats in the Majlis had problems of their own to contend with, as a long-awaited rebellion erupted in 1865.

165,000 rebels rose up across the width of Iberia, but the uprisings being uncoordinated and badly-planned. The largest and most dangerous rebellions were situated in eastern Iberia, where the Andalusi Army was quickly dispatched, eventually crushing the revolts in the decisive battles of Mursiya and Gharnatah.

With the only legitimate threats quickly eliminated, the Majlis were able to end the other uprisings with compromise instead of force, promising constitutional reform and significant concessions to the reactionary rebels.

And they did exactly that, with the Royalists forcing another bill into law just months later. The Sultan had had very little power until then, forced to play the part of a figurehead, sponsoring fruitless programs and attending pointless functions. With the Sultanic Reform, however, Utbah would be granted the power to appoint new members of the Majlis, dismiss field marshals and generals, and - most importantly - ratify any new legislation.

With that, in a single stroke of ink, a sultan holds real power in Al Andalus for the first time in a century.

Sultan Utbah would waste no time in using his newly-established authority to great effect, immediately admitting several eccentric family friends into the Majlis al-Shura. And just two weeks later, he vetoed his first piece of legislation in the assembly, refusing to ratify a bill that would open the officer corps to commoners.

The Sultan would not use his powers for anything noteworthy until early in 1865, however, when he founded a national police organisation. Dubbed the "Sultanic Guard of Andalusia", or simply the SGA, this organisation would serve as the secret police of the regime, devoted to combatting state enemies, thwarting political terrorists and countering revolutionary movements.

With help from the SGA, the Andalusi Army quickly restored order in Iberia, bringing an end to the many revolts, riots, uprisings, protests and strikes plaguing the country. By the summer of 1865, militancy would be brought to check once more, finally ending the threat of further rebellions for the near future.

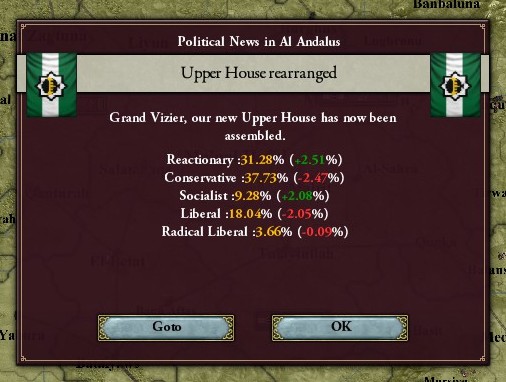

The covert tactics employed by the secret police would quickly become infamous across much of Europe, however, as they gradually weeded their way into every organisation or society of note. Combined with the recent string of uprisings, this proved enough to fuel a surge in conservatism all across Iberia in 1865, with more people flocking to support the Moderates than ever before.

The Imperialists, meanwhile, had been slowly advancing their own agenda. They had little popular support and were adamantly opposed by the reactionaries, making it impossible to launch any colonialist efforts, but they were able to extract trading privileges and extraterritoriality from several African kingdoms, laying fertile soil for future ventures in the continent.

And by 1865, they were confident enough to publicly campaign on the promise of domestic peace and imperialist glory, hoping to rouse enough support to begin colonisation efforts in Africa. The light of Islam had to be brought to the uncivilised nations of the world, after all, and who better to take up that mission than Al Andalus?

These publicity campaigns wouldn’t occupy the public’s attentions for very long, however, as newspapers were quickly taken by storm with something else entirely:

Socialism, the snake that threatens to strangle the very identity of Al Andalus, had gained its first supporters in the Majlis. Traitorous extremists in the assembly professed public support for the “Workers’ Party of Iberia”, an institution devoted to implementing socialist ideals peacefully - as if such a thing were even possible.

Socialism had been gaining support and popularity despite the anti-socialist laws of 1860, so Grand Vizier Musad couldn’t outlaw the political party without inciting yet another rebellion, forcing him to formally admit the "Socialist Faction" into the Majlis al-Shura. It would quickly attract the opposition and scorn of other parties, however, with the blue-blooded aristocrats denouncing it as a populist instrument to overthrow the Majlis and Sultan.

And yet again, the world is on the cusp of great change, as the massive potential of this new ideology is only gradually revealed. Monarchy reigns from Boston to Beijing, but little do these kings and sultans and khans know that one day very soon, red banners will be hoisted over their bodies as workers all across the globe call for world revolution.

World map: