Part 89: Parasites of Patriotism

Chapter 9 - Parasites of Patriotism - 1865 to 1870Al Andalus and Morocco - the rivalry between these empires was amongst the greatest in history, borne from ambition and zeal, immortalised in thousands of poems and sagas, spanning hundreds of years and costing millions of lives. They had been fierce enemies since the 1300s, fighting countless battles and waging untold wars during that time, with the two powers alternatively crushed and victorious in ultimately-futile wars. This was their history, and as things stood, it would be their future as well.

Tensions between Al Andalus and Morocco reached a nadir in the nineteenth century, a wave of hostility that peaked in the War Scare of 1865, when Moroccan authorities barred Andalusi merchants from trading in Libya, Cyrenaica, Jolof and Mali - all countries within their sphere of influence.

Viziers in the Majlis al-Shura immediately denounced the Moroccan government, accusing them of unlawfully imposing puppet regimes in Libya and Jolof, and demanding open access to them. In an aggressive show of force, Grand Vizier Musad dispatched the army to the Andalusi-Moroccan border at Qartayannat, threatening war over the matter.

The Berbers retaliated decisively, postponing military leave and sending a large fleet of frigates to patrol the Straits of Gibraltar, a clear challenge to Al Andalus. This sudden escalation alarmed the Grand Vizier, who quickly lost his nerve, backing down and de-escalating the war scare.

This feeble exchange was not met well in the national press, with the Andalusi Times criticising the government’s response to the Moroccan escalation. A series of disparaging articles were published over the next few weeks, condemning the Grand Vizier as an unpatriotic, hapless fool unable to properly lead the nation.

These attacks grew in intensity and vigour as the year progressed, eventually culminating in a huge swoop for the Times, who published a scandalous report on the Grand Vizier’s nightly visits to the house of his deputy-vizier’s wife…

Musad responded by demanding that the Majlis shut down the newspaper, feverishly claiming that this ‘unfounded attack on his character’ was nothing but slanderous libel. And though the Grand Vizier found some support in his party, the liberals in the assembly staunchly blocked his insane motion, loudly mocking his love life as they did so.

With his desperate last gasp ending in failure, Grand Vizier Musad finally bowed to public pressure and resigned from his position, retiring to his estates in the countryside. This, in combination with their disastrous handling of the war scare with Morocco, meant that Royalist popularity had plummeted over the course of 1865 - allowing the liberal Imperialists to gain ground in the assembly.

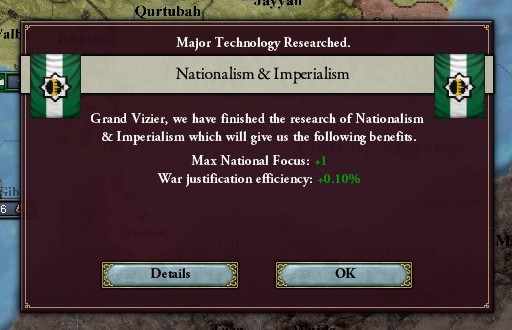

And by campaigning on the promise of a strengthened navy and colonial glory, the Imperialists managed to win their first term in the Majlis, landing a stinging blow to conservative elements in the country.

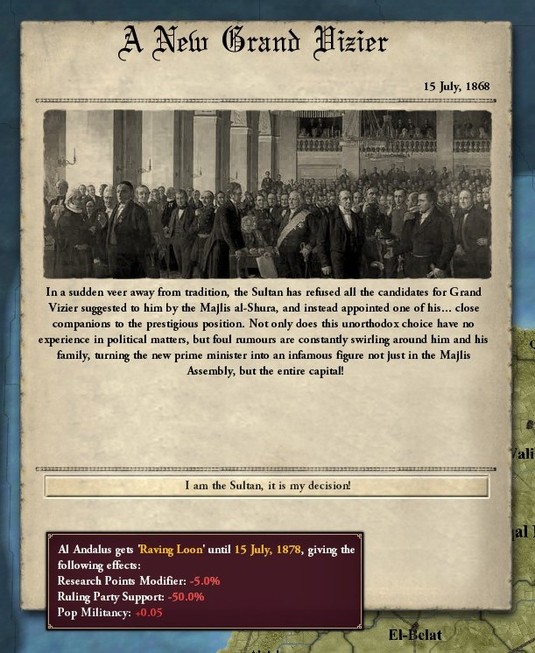

Sultan Utbah had remained neutral thus far, but this was a step too far. He couldn’t openly defy the will of the Majlis, but he managed to partially-circumvent them by personally appointing the new Grand Vizier, naming one Tawfiq al-Mawsili to the esteemed position. An aged nobleman and firm reactionary, Tawfiq was almost certainly a puppet of the Sultan, with his selection quickly drawing denunciations from the liberals in the Majlis.

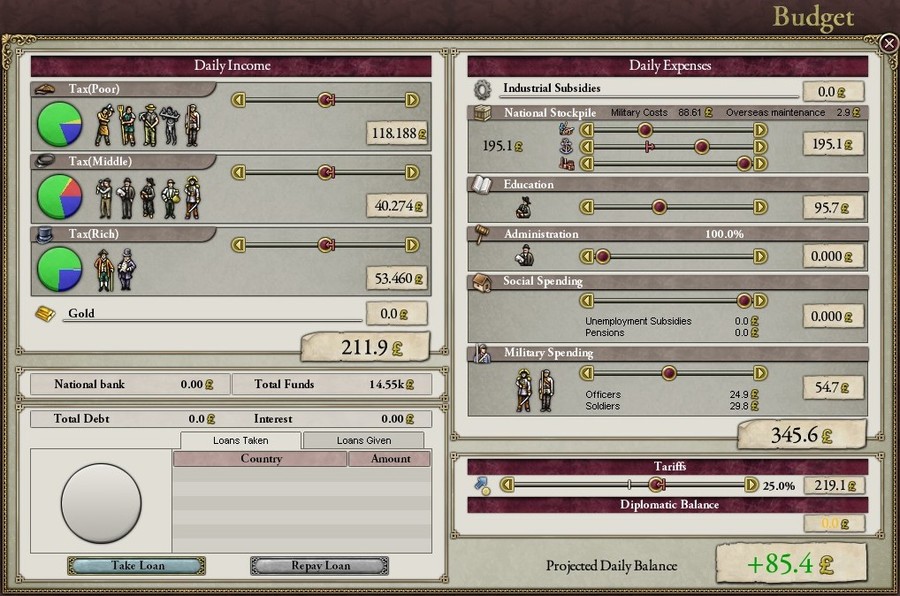

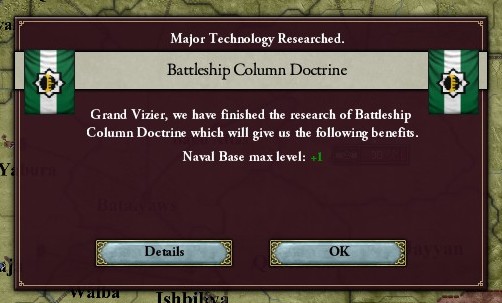

The Imperialists quickle turned their attention to actual governance, cutting taxes,, military spending and education funding, with tariffs to be gradually lowered over several years. The surplus income, meanwhile, was redirected into the fulfilment of the terms of the Naval Act of 1865 - legislation that mandated the expansion of the Andalusi Fleet, renewed sailor recruitment and training, and the erection of new harbours and ports.

These naval programs were not cheap, however, with the costs estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands of dinars - at the very least. To ensure the income stayed in the black, the liberals launched a series of financial reforms targeting tax efficiency, overhauling the stock exchange and establishing business banks throughout the country.

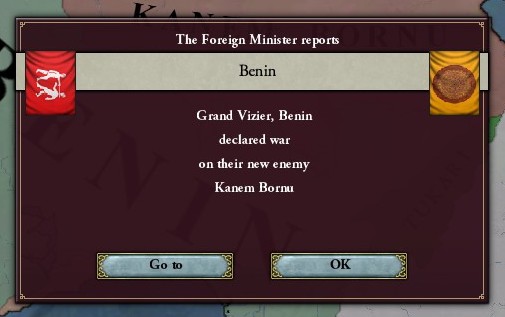

Further south, Benin had just joined the civilised nations of the world, though it was still unproven against the Great Powers. Ambitious and confident, Oba Eweka was determined to rectify that, staging a border conflict and launching an invasion of Kanem Bornu.

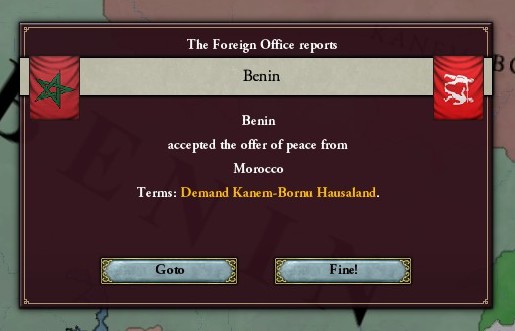

The Almoravid Sultanate of Morocco, however, considered everything southwest of the Sahara Desert to be in their sphere of influence - and they weren’t going to let the upstart pagans in Benin change that. So their armies were quickly dispatched southward, with Morocco formally intervening in the conflict a few weeks later, plunging the entirety of West Africa into war.

Needless to say, Benin’s chances of emerging victorious weren’t looking good.

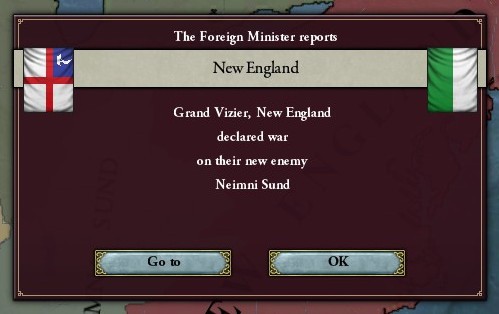

Across the Atlantic Ocean, another war had sparked between New England and Neimni Sund. And as if the odds weren’t already stacked against the Irish, the Republic of Ibriz was also involved this time, with the New English demanding assistance in their conflicts before agreeing to a joint invasion of Albionoria.

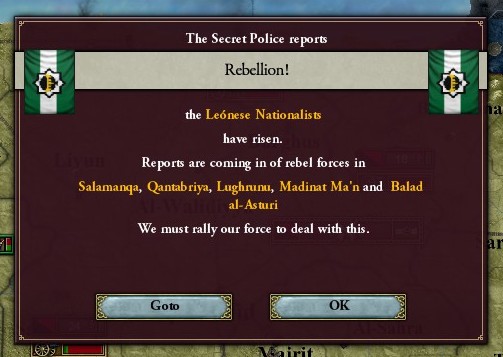

Back in Al Andalus, another uprising wracked the peninsula early in 1866, with Leónese nationalists launching a coordinated rebellion all across northern Iberia. Even the liberals wouldn’t stand for separatism, so the Andalusi Army was sent to quell the uprising.

And that they did, with the army emerging triumphant in four short, decisive battles, re-asserting direct military rule in northern Iberia with brutal force.

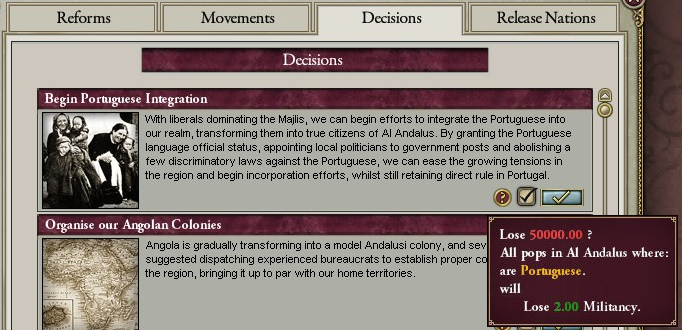

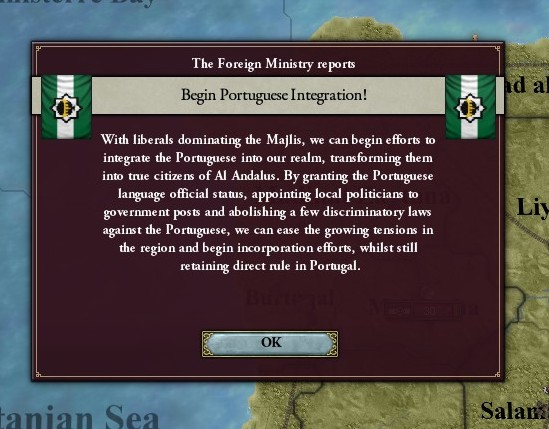

Another rebellion had been subdued, but it was becoming increasingly clear that the Portuguese, Leónese and Castilians would continue to be a disruptive and agitating force in Iberia. Something had to change, with Makki al-Isbiliyya - a liberal vizier in the Majlis - suggesting that efforts be undertaken to formally incorporate these fringe cultures into Al Andalus.

This proposal was met with enthusiasm from the Imperialists, who were determined to establish a lasting peace in Iberia. They began in Portugal, the richest and most populated region in the north, by appointing one Pedro Freitas as governor - marking the first time in centuries that an ethnic Portuguese ruled in Portugal. This was quickly followed by a bill that granted the Portuguese language limited recognition in Al Andalus, allowing it to be used in local businesses and commerce. And a few weeks later, the liberals managed to abolish several laws that dated back to the Jizrunid era, whereby locals faced discrimination and prejudice in regional elections, massively favouring the Andalusi minority.

Much more would be required before the Portuguese could become an accepted culture in Al Andalus, but this was a start.

More importantly, several new naval bases completed construction in the summer of 1866, allowing ships to be constructed, maintained and repaired in Mediterranean harbours.

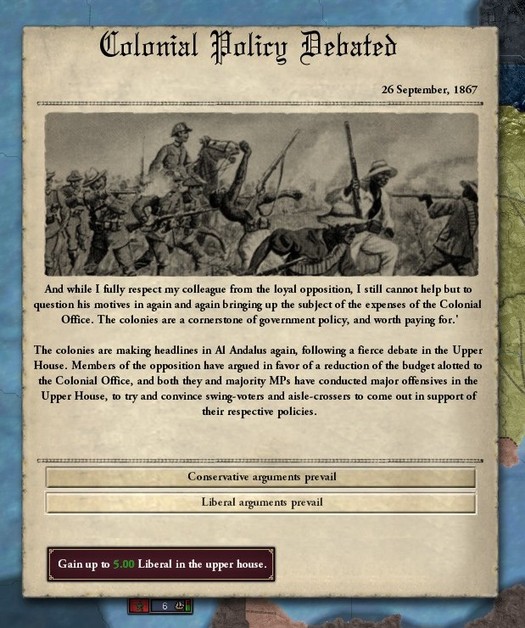

And with every passing day, shipyards were launching new vessels into open water, gradually reinforcing the Andalusi Navy. This steady expansion ignited another debate over colonial policy in the Majlis, with the liberals insisting that new colonies were necessary if Al Andalus was ever going to challenge Morocco, whilst the reactionaries and socialists remained firmly against renewed imperialism.

The liberals had been growing in strength, however, and they finally managed to secure the majority they needed to begin colonial efforts abroad. Grand Admiral Sayf al-Talasi immediately began planning for his first colonial war, pinpointing the Kingdom of Kongo as an especially strategic and potentially-valuable target.

The West African War, on the other hand, was still raging with no end in sight. Benin had stunned Western observers so far, with Beninese armies quickly occupying Kanem Bornu before invading Mali, crushing their irregular levies and repelling Berber armies as they did so. Morocco would only intensify their war effort over the next few months, however, sending almost 100,000 Berbers and Indians to halt the Beninese advance in Mali.

Pushing across the storm-tossed waves of the Atlantic, Neimni Sund had collapsed to the combined Ibrizi-New English invasion, forced to unconditionally surrender within months.

Once peace with Neimni Sund was signed, the Revolutionary Council of Ibriz dispatched diplomats and marshals to New England, so the allied powers could begin planning for their invasion of Albionoria. Once the northern union was defeated and dissolved, Ibriz could begin preparing for war with New England, and finally reclaim their rightful place as the master of North Gharbia.

The Butler Queen of New England, however, had other ideas.

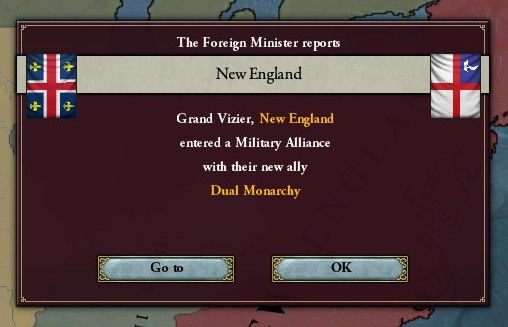

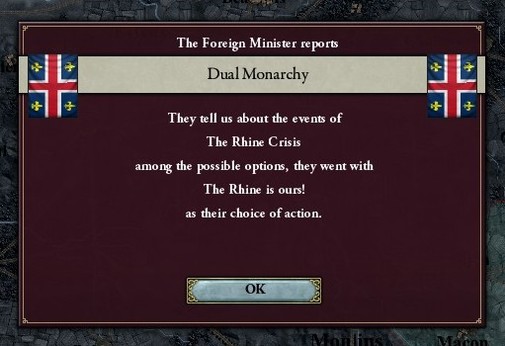

Whilst Ibrizi armies were fighting their way through the humid swampland of Neimni Sund, the Butler Queen had been meeting with diplomats from France, hoping to win the Dual Monarchy as an ally. And by the winter of 1867, these negotiations came to a successful conclusion, with the two powers signing a defensive pact in Paris.

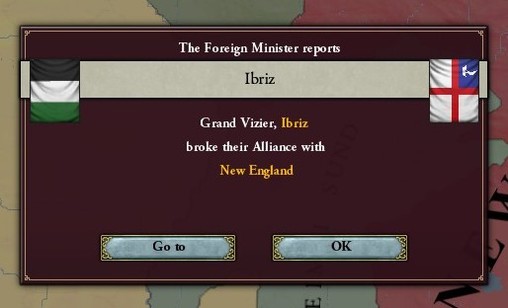

The public declaration of this pact infuriated politicians in Ibriz, unsurprisingly, with the Revolutionary Council immediately terminating their alliance, expelling their diplomats and threatening war with New England. No amount of posturing could hide the fact that Ibriz had been played, however, and now found themselves surrounded by three hostile powers. The balance in North Gharbia was quickly shifting against them.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the naval expansion program was finally completed. The Andalusi Navy now boasted thirty vessels, counting amongst them eight man-o’-wars, twelve frigates and ten transports, all waiting for their first taste of combat.

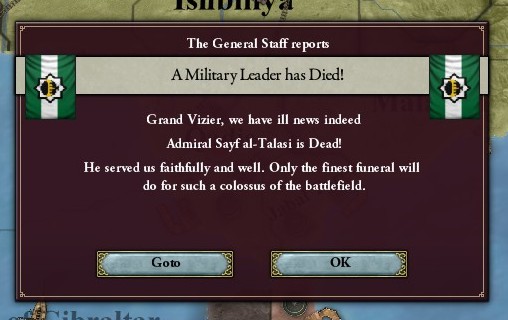

This rapid expansion was overseen by Sayf al-Talasi himself, with the veteran admiral having earned fame and glory for his exploits during the Tirruni Wars. The war hero died just a few weeks before its completion, however, with his state funeral attended by hundreds of thousands of commoners and peasants.

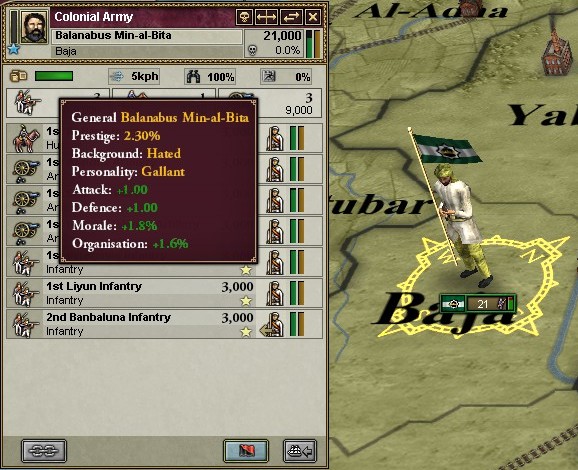

Nonetheless, this navy would safeguard Andalusia’s future colonies, but those colonies had to be won first, and that couldn’t be done without an army. So over the course of 1867, a liberal-led colonial army was recruited and trained, numbering almost 21,000 soldiers by the end of the year.

A prominent vizier and commander in Balanabus Min-al-Bita was appointed commander, and because this force would primarily serve overseas, the Imperialists granted Balanabus complete authority and autonomy whilst leading the colonial army, trusting him to act in the interest of the Sultanate above all else.

This was a double-edged blade, however, as it would see colonial commanders gradually accumulate power through their conquests overseas.

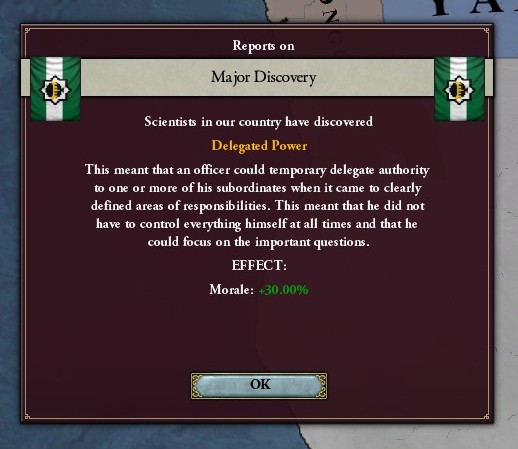

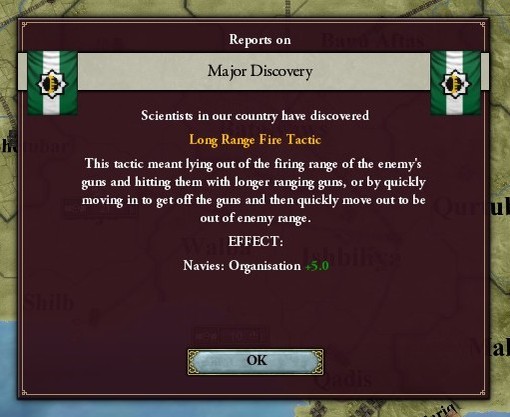

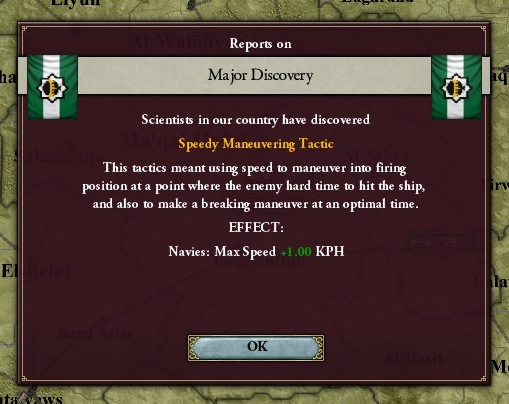

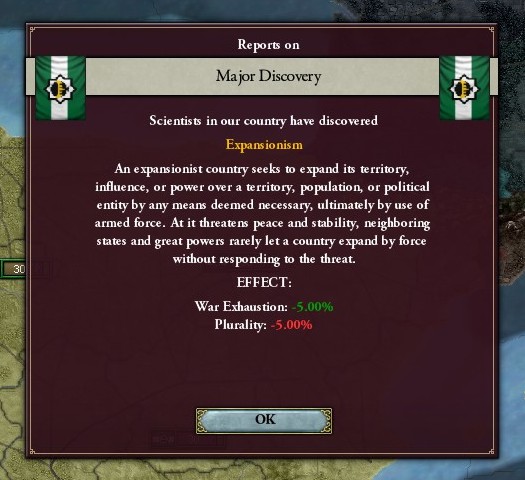

These naval and army expansions were essential, of course, but just as important were the doctrinal and tactical advancements made over the past few years. The development of steam warships meant that naval tactics had to be adapted and modified, with long-range projectiles and speedy manoeuvring gaining prominence, and military thinkers even insisting that ramming ought to be reintroduced into naval strategy.

By the early days of 1868, the Imperialists were finally confident enough to launch their long-awaited war. A propaganda campaign had drummed up support for ventures abroad, centred on Andalusia’s "destiny" to spread civilisation to the primitive nations of the world, with the public now openly calling for colonial wars and prestigious colonies.

And the Imperialists would deliver.

The navy was dispatched on its first mission in July of 1867, with the war fleet escorting the transports down the coast of West Africa, finally coming to a halt at the estuary of the Congo River. There, Balanabus Min-al-Bita personally declared war on Kongo, securing the beachhead and quickly storming the lightly-defended coastal fortresses.

Whilst the Andalusi began capturing outlying villages and cities, the king of Kongo desperately raised his levies, fielding almost 30,000 soldiers in the space of weeks. Balanabus was confident in his martial superiority, however, and a stunning victory quickly followed, with the entirety of the Kongolese army gunned down in three short, bloody hours.

Facing hopeless odds, the Kongolese sued for peace shortly afterwards, agreeing to cede the Angolan coast to Al Andalus.

News of this decisive victory quickly reached Iberia, where raucous celebrations erupted throughout Qadis, encouraged by the jingoistic liberals. This adoration wasn’t universal, however, with conservatives and socialists condemning the rampant imperialism, claiming that the liberals were exploiting Andalusi nationalism to bolster support for their colonial adventures. Sultan Utbah himself voiced opposition to the liberals, branding them "parasites of patriotism" in a scathing attack.

The Imperialists were deaf to the criticism and reprimands, however, having already embarked on their next war.

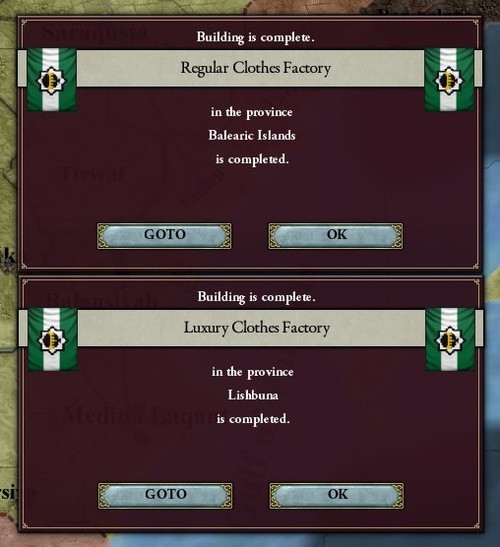

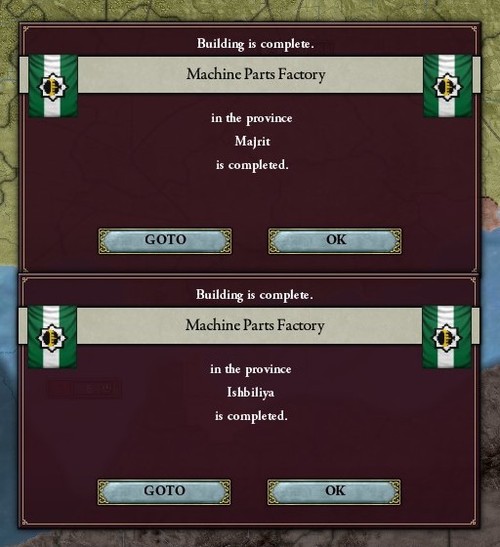

In Iberia, meanwhile, the Moderates’ popularity with the general public continued to grow. Funding the growing class of capitalists, who were quickly becoming an influential force in Al Andalus, several new manufactories were established over the course of several years.

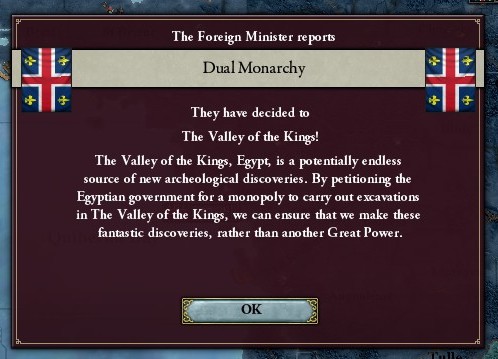

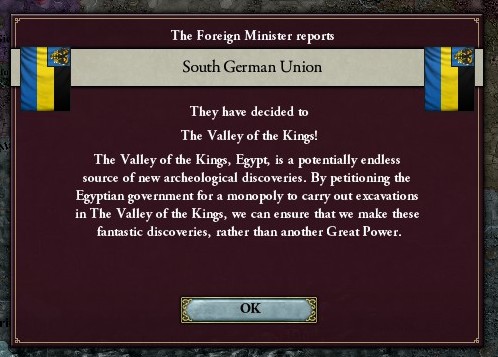

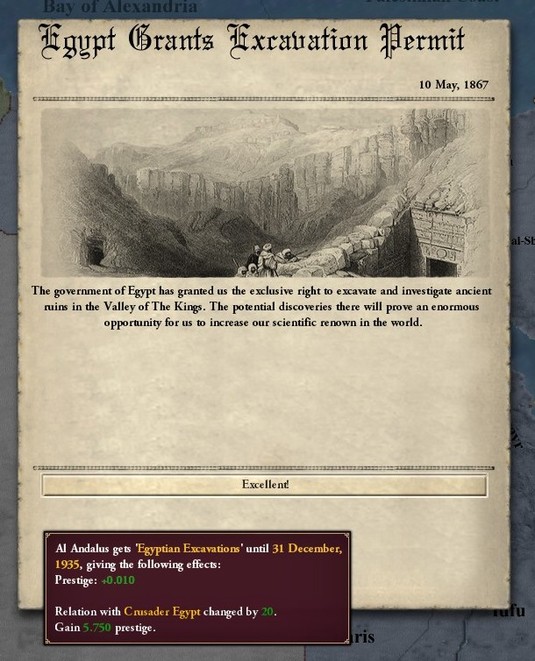

The Moderates didn’t have the financial backing to launch many cultural programs, however, with large parts of the Majlis seeing them as a frivolous waste of money. Other great powers didn’t have the same fetters, and with the field of Egyptology growing in popularity, they began to seek excavation permits from the government of Crusader Egypt.

There was a treasure trove of prestige waiting in the dark tunnels and concealed chambers dotted across Egypt, and the Moderates didn’t want to miss out. Several moderate viziers thus delivered an impassioned speech to the Majlis, in which they insisted that Andalusia’s global standing could only benefit from participating in these cultural crazes, and would only suffer if they didn’t compete for them.

And the Majlis, after months of careful consideration, finally agreed to fund a small expedition to Egypt.

Diplomats were thus dispatched to Alexandria, where King Apanoub personally awarded them a permit to begin excavation efforts, perhaps hoping to improve relations with Al Andalus.

A massive expedition was quickly outfitted in Qadis, consisting of dozens of archaeologists, scientists, mathematicians, chemists, naturalists, botanists and engineers, with the party arriving at Egypt within a scant few weeks. And they immediately met with impressive discoveries, unearthing the tomb of a long-forgotten pharaoh, along with countless ceremonial knives, jewelled obelisks and bas reliefs - priceless artefacts that would tragically disappear, only to resurface in Qadis a few months later.

These triumphs contributed to the flowering of Egyptology, attracting an influx of archaeologists, scholars and explorers from Europe. There was also a growing interest in discovering the source of the Nile River, with several expeditions launched deep into Sudan and Uganda, missions that ultimately ended in failure.

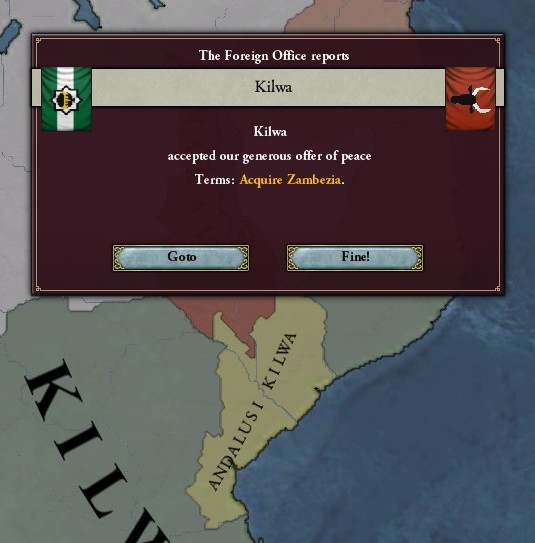

These were simply petty distractions, however, the Majlis was still firmly focused on colonial enterprises. The war with Kilwa had been progressing very well, with the colonial army seizing the coastlines before pushing inland, and crushing the Kilwan army in July of 1869.

With the Kilwans defeated on the battlefield, the Andalusi quickly seized surrounding cities, before marching on the regional capital. Once its medieval walls were reduced to rubble, the Kilwans finally surrendered, ceding a stretch of coastal land to Al Andalus.

Two victories in as many years, it couldn’t get much better than that. The ambitions of the Imperialists went far beyond mere coastal holdings, however - and as they began charting sea routes across the eastern ocean, their grand plan slowly began to take shape.

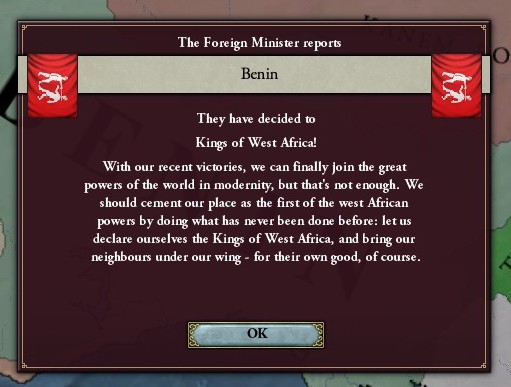

The West African War also came to an end that year, deep into October of 1869. Stunning observers in Europe and Gharbia, Benin had emerged with a decisive victory, having crushed the armies of Morocco in numerous battles throughout the past two years. This triumph transformed Benin from a relatively minor, overlooked kingdom into a regional power, and one to be reckoned with at that.

And they weren’t done just yet.

Oba Eweka summoned his court to make a grand declaration in November of 1869, inviting foreign dignitaries and notable emissaries to the event as well, eager to capitalise on his success. And there, he proclaimed himself the "King of West Africa", a title that had no precedent in the region.

King Eweka was ambitious, however, and he would enforce his will if necessary.

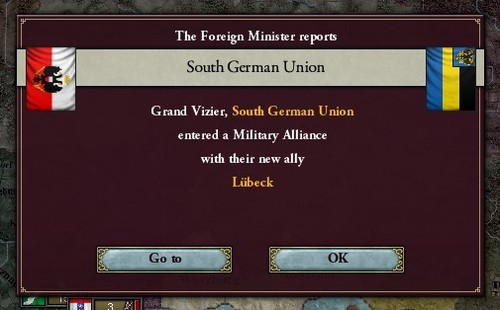

Further north, meanwhile, Europe had been relatively quiet over the past five years. The Dual Monarchy had focused on internal development, Al Andalus was devoted to colonial ventures, and the South German Union gradually encouraged unification amongst the north German minors.

This lull in tensions wouldn’t last very long, however, coming to an end in the dying days of 1869.

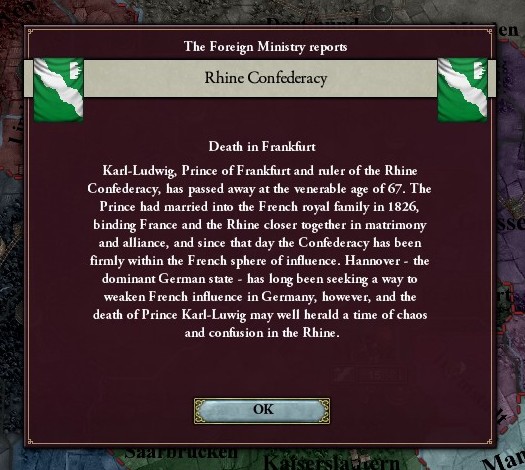

The Rhine Confederacy had been in matrimonial coalition with France since 1826, when Prince Karl-Ludwig married into the Roman dynasty, but this marriage would prove to be a strained, childless chore to both parties. And with the death of Karl-Ludwig, his nationalist brother ascended to the princedom, marking the end of the personal union between France and the Confederacy.

That should’ve been the end of French influence in the region, but Paris wasn’t going to surrender the Rhine, not without a fight. An additional 20,000 troops were thus dispatched to Frankfurt that very same night, drawing furious condemnations from the rest of Europe.

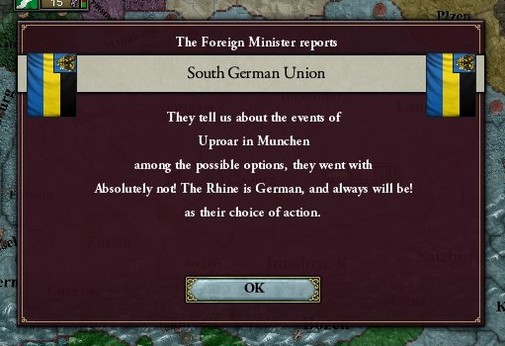

Protestations wouldn’t suffice, however, not for the South Germans. As thousands of soldiers poured across the Rhine, the new Prince of Frankfurt called for assistance from his fellow Germans, determined to retain his sovereignty.

And the Bavarians answered, issuing an ultimatum to Paris: withdraw from the Rhine, or face war.

The first morning of 1870 arrived, and with it, the ultimatum went unanswered. True to their word, the South German Union immediately declared war on the Dual Monarchy, with bloody battles exploding all along the French-Bavarian border.

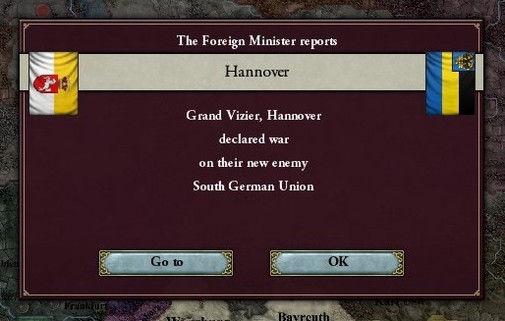

This was exactly what King August-Wilhelm had been waiting and hoping for: war between the two juggernauts of the continent. Determined to retake his rightful position as the dominant German state, Hannover declared war that very same day, with troops marching on Nuremberg before night had arrived.

It was the first day of 1870, and Europe had exploded into war.

World map: