Part 92: The Scramble for Africa

Chapter 12 - The Scramble for Africa - 1880 to 1886Dominated by arid desert and dense jungle, Africa had always been a hostile and defiant land, largely uncharted by locals and foreigners alike. It perpetually hovered at the edges of maps, always beyond the borders of the world’s greatest empires and kingdoms, content with leaving it unclaimed and unconquered - it was, after all, far too large and wild to tame.

By the nineteenth century, however, nothing could be further from the truth. The sheer riches of Africa were already legendary, with rumours of the immense iron deposits, vast gold mines and boundless diamond veins quickly spreading across the old world, where campaigns for colonisation and imperialism were quickly gaining ground. These unequalled riches did not come without inflamed tensions, however, as the European powers began posturing and competing to expand their influence and territory in the continent.

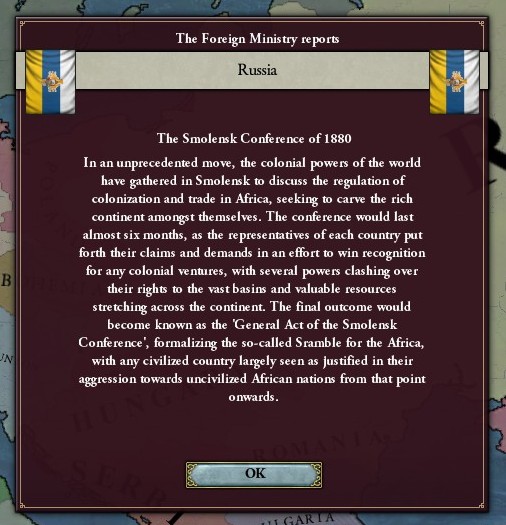

As a result, at the height of the summer of 1880, the Tsarina of Russia formally invited the colonial powers of the world to a great conference to discuss the regulation of colonisation and trade in Africa.

Sixteen nations sent representatives and emissaries to Smolensk, and for five long months, they argued and debated and bickered endlessly. Several dignitaries presented dubious claims to vast tracts of land in Africa, whilst others demanded freedom of trade in the Niger and Kongo basins, and others still insisted that ‘civilising missions’ be dispatched to end slavery and paganism amongst local tribes and polities.

When the conference finally closed late in the year, however, the colonial powers had agreed on just one thing: that the vast riches of Africa were there for the taking, by those willing to seize them.

The sabre-rattling Imperialists immediately drew up plans to seize vast tracts of land in every direction, with exploratory missions dispatched to Benue, Ruzizi, Songwe and Zambezi, quickly followed by armed expeditions and settler parties.

A crisis had already erupted in Qadis, however, where the Iron Vizier was assassinated in broad daylight. His tenure as Grand Vizier, however brief, would be glorified and lauded by countless politicians and historians in years to come, and his brutal assassination only cemented his mythos.

With the Majlis collapsing into its usual rancour, however, the Imperialists wasted no time in choosing a new Grand Vizier. Hoping to earn the public’s support for colonial ventures, they named Murad al-Din to the esteemed position, with the famous explorer-turned-politician commanding great popularity amongst the masses.

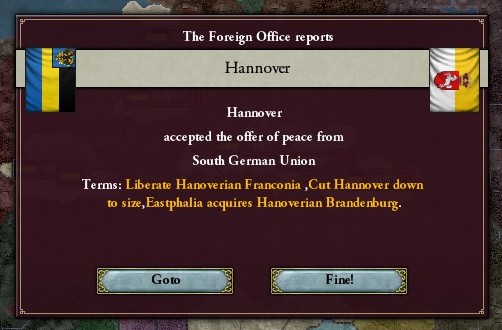

To the north, meanwhile, war erupted in Germany. The Kingdom of Hannover had quickly recovered from their devastating defeats to France and Bavaria, completing their reparation payments and fielding a new army, to the anxiety and dismay of the South Germans. This rapid rearmament campaign continued until the spring of 1881, when the chancellor of the South German Union finally intervened, declaring a preventative war on Hannover.

And in Britain, the Celtic Union declared war on the Dual Monarchy, with the Dublin parliament determined to take advantage of their weakened enemy. And surprisingly, they didn’t claim England at all, instead determined to seize Wales - rich in minerals and, more importantly, populated by Celts.

Across the width of Europe, meanwhile, the Dual Monarchy took advantage of this chaos by declaring war on the Celtic Union, determined to retake the territories ceded to their historic enemy.

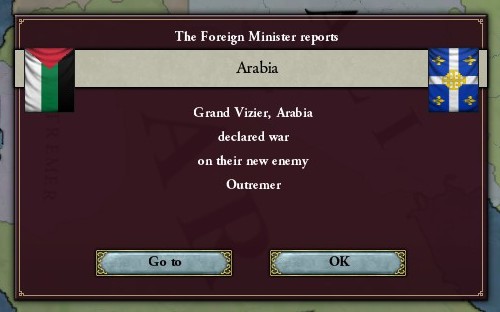

Just a few weeks later, the simmering tensions between Muslim and Christian exploded into conflict in the Middle East, where the Caliphal Alliance invaded the Kingdom of Outremer, backed by Crusader Egypt.

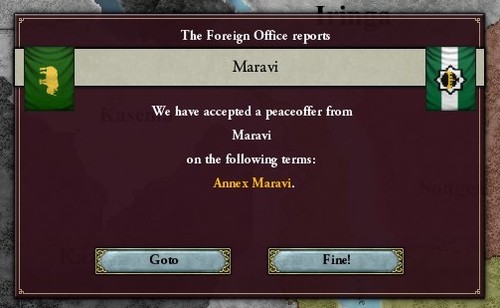

In Africa, meanwhile, the Andalusi continued with their rampant imperialism. Under the command of Balanabus Min-al-Bita, the colonial army invaded the petty tribal kingdoms dotting Angola and Mozambique, securing trade routes and seizing strategic cities, executing their kings and chiefs when they didn’t submit unconditionally.

Balanabus, who was quickly accumulating prestige and authority with every victory, even raised an autonomous navy late in 1881. Consisting largely of wooden frigates, the navy transported 8000 soldiers across the Mozambique Channel, landing them along the northern coast of Madagascar in the summer of 1882. From there, they marched inland and seized the capital of Antananarivo in a sudden offensive, quickly subjugating surrounding villages and towns over the next few weeks.

In fact, by January of 1882, the colonial possessions of Al Andalus stretched from the Benue to the Kunene rivers in the west, the Rumuva to the Zambezi rivers in the east, and across the entirety of the island of Madagascar. Within two decades, the Imperialists had managed to conquer an area that surpassed a million square miles - over five times the size of Iberia.

And the vast majority of that land was centralised under one man - Balanabus, self-proclaimed conquerer of the Kongo.

As his influence and authority continued to grow, however, so did his ambitions. With his territories and revenues swelling, Balanabus began to recruit and arm natives in the summer of 1883, intent on building an army loyal to him and him alone. Back in Qadis, there were very few viziers willing to protest, and those who did were quickly silenced with large pouches, heavy with coin.

This would not be the extent of Balanbus’ ambitions, however, with the commander demanding an inch and seizing a mile.

In the humid summer heat of his new capital, Balanabus declared himself the "Khedive of the Kongo", dispatching emissaries to obtain recognition from the Sultan and Majlis. Grand Vizier Murad immediately refused this absurd request, even going one step further, and warning him that any attempts to secede or seize autonomy would be met with military force.

Balanabus Min-al-Bita continued to style himself khedive, but the next few weeks passed without further incident, and Grand Vizier Murad let the tensions dwindle. For now.

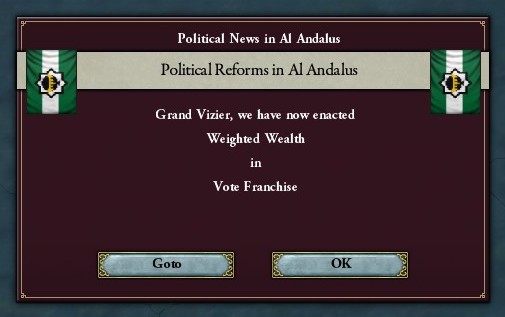

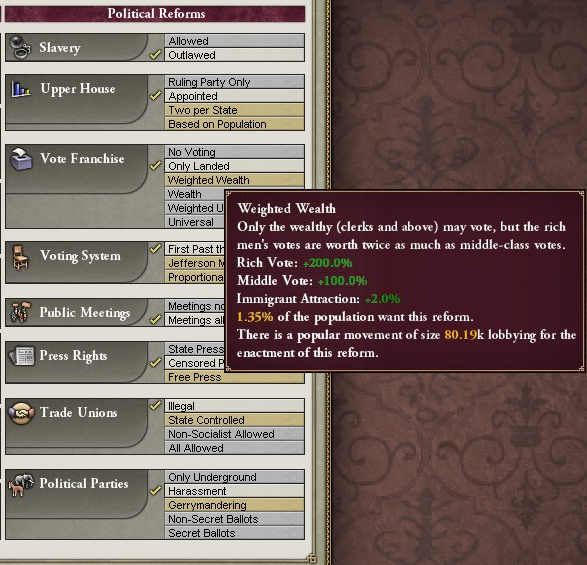

Back in Qadis, meanwhile, the Grand Vizier had other problems to tackle. The assassination of the Iron Vizier had led to an outpouring of liberalism, with thousands of commoners taking to streets in the weeks leading up to his funeral, defiantly marching in support of his ideals. The Imperialists saw this as an opportunity, cleverly installing outspoken liberals amongst their ranks, preaching for an expanded franchise and reformed voting laws - and within weeks, these mourners were transformed into marchers.

And late in 1883, at long last, the aristocrats of the Majlis yielded. Fearing the outbreak of further uprisings, the moderates largely agreed to support limited reform, and the voting franchise was extended to the capitalists of Al Andalus.

To the north, on the other hand, peace accords had finally settled the war in Britain. And remarkably, it was the Celtic Union who emerged triumphant, having rampaged southward and captured London within months.

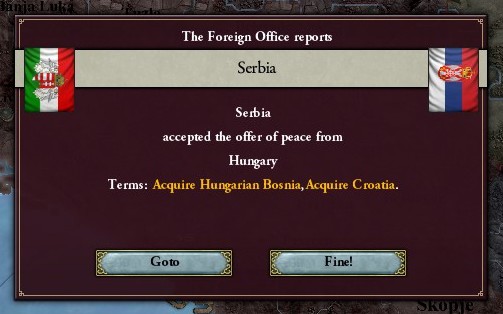

The war in Germany was still raging, but peace had also returned to the Balkan peninsula, where an expeditionary force of 20,000 Frenchmen had shifted the conflict decisively in favour of Serbia. The king of Hungary was forced to cede Bosnia and Croatia in the ensuing peace treaty, reversing all of his hard-won gains in a matter of months.

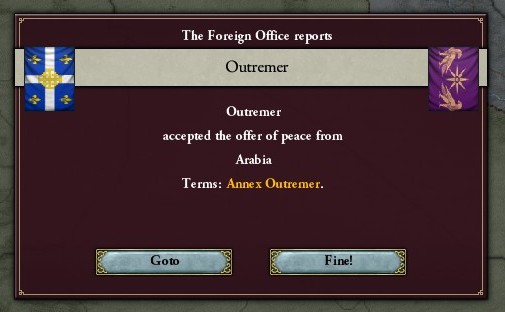

And in the Near East, the armies of Arabia and Armenia stormed across Outremer with ease, seizing Acre and Jerusalem before the new year had arrived. The Egyptian armies were busy quelling an uprising in Sudan, and with the isthmus of Suez left dangerously exposed, King Apanoub agreed to end their war.

And with that, almost fifty years after the Congress of Cádiz first established it, the Kingdom of Outremer was finally vanquished.

It wasn't long before the eyes of the world turned back on Qadis, however.

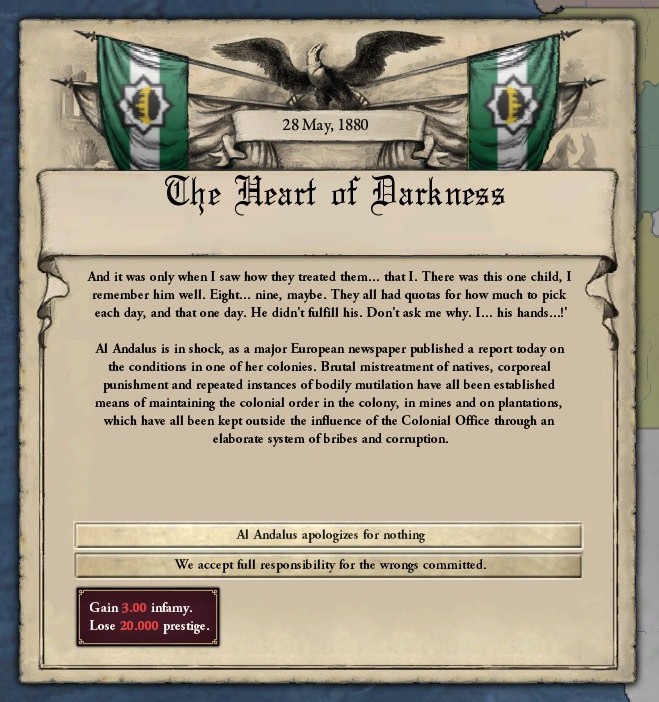

An undistinguished officer in the employ of Balanabus Min-al-Bita had, upon his return to Europe, published a series of novels and articles that exposed the blatant cruelty of his regime. According to these writings, Balanabus had levied tens of thousands of natives over the past decade, forcing them to work the vast farmlands, mine for precious ore, extract wild rubber, improve local infrastructure, establish manufactories and strengthen his autonomous army - with the peasantry facing torture and execution if they dared defy him.

These revelations were met with outcry and denunciations across much of Europe, but Grand Vizier Murad promptly denied them, claiming that these articles were the deranged imaginations of a lunatic.

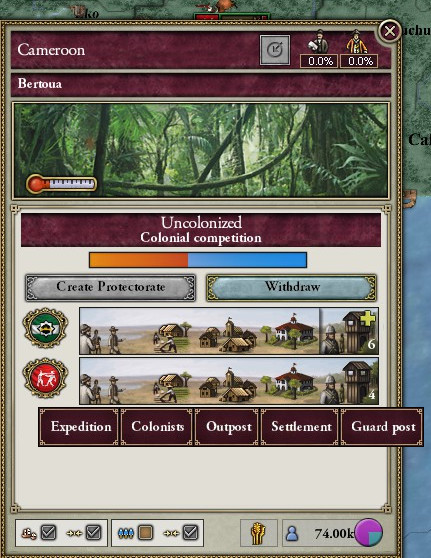

The self-proclaimed khedive, on the other hand, was focused entirely on the colonial crisis brewing in Cameroon.

Balanabus had dispatched an expedition early in 1882, with the party reaching the Benue before summer’s end, planting an Andalusi flag along the riverbank. That very same day, however, a heavily-armed company from Benin City crossed the river. Ignoring Andalusi claims, they quickly met with the tribal leaders that dominated the region, hoping to secure a protectorate over them. Realising that he was losing the race for Cameroon, Balanabus quickly retaliated by dispatching another expedition - this time accompanied by soldiers and colonists.

In the months that followed, an uneasy peace settled between the two expeditions, with the Andalusi slowly but surely gaining the upper hand through their settlements, guard posts and carefully-crafted treaties.

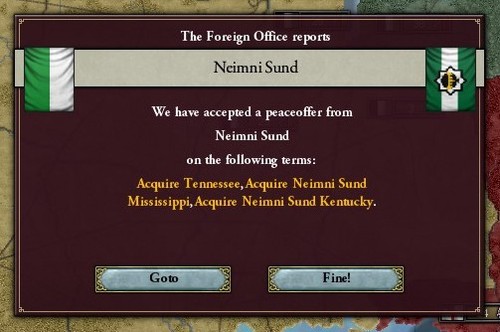

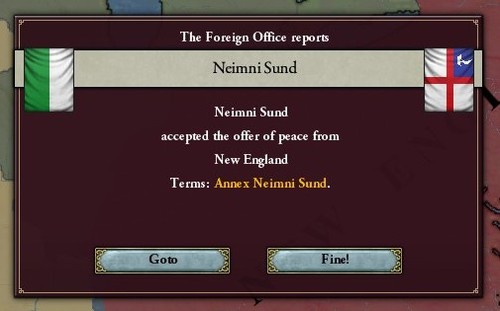

Across the storm-tossed waves of the Atlantic, meanwhile, the Revolutionary Republic of Ibriz and Kingdom of New England had - in a rare occurrence - just signed a pact. Temporarily united in alliance, the two powers launched a coordinated invasion of Neimni Sund in April of 1882, quickly crushing any resistance and partitioning the rump state between them.

Back in Europe, the Russian Empire was rearing its head for the first time in decades. Its rearmament program had been very successful, and with Russia now fielding the largest army in Europe, they launched another invasion of Scandinavia and seized another slice of the Baltics.

Triumph was quickly followed by tragedy, however, as Tsarina Dobroslava finally died at the venerable age of 80. Condolences quickly arrived from the other great powers, with Al Andalus even sending their crown prince to attend her funeral, as well as the coronation of her nephew and heir: Emperor Alexandrovich.

It wasn’t long before the prime ministers, chancellors and grand viziers of Europe turned eastward, however, where the Republic of Japan had just made a momentous announcement…

The Rajput states had been firmly within the Japanese sphere of influence for decades now, with the Japanese seizing coastal ports, demanding trading privileges, and slowly coming to dominate their internal and foreign affairs. By the 1880s, the Rajput princes had only the thin veneer of independence, with Japanese officials installed in any positions of real power.

And in October of 1884, this veneer was finally ripped away, with the shushõ of Japan formally consolidating the princely states into a single authority - the Japanese Raj.

A clear challenge to the Berber Raj, the Almoravid government immediately denounced this as rampant expansionism, and began a program to expand and upgrade their navy.

It was becoming increasingly obvious that the future of warfare lay in the seas, and fortunately for the Andalusi, almost two decades of imperialist rule had left them with a powerful navy - the Iron Fleet, now numbering almost 70 man-o'-wars, monitors and ironclads.

Despite this rapid expansion, however, the Andalusi Fleet was still outnumbered by the Almoravid Navy. If the Moroccans could concentrate the entire strength of their navy in one battle, then the Andalusi would almost certainly be overpowered, through numbers alone.

So with heavy funding from the Imperialists, the admiralty began experimenting with naval design, sparking a technological race in which they developed battleships - a decisive upgrade from earlier ironclads. Grand Vizier Murad managed to pass another expansionary law late in 1884, ordering five new warships based on their design.

In Germany, meanwhile, the South German Union had been waging war on Hannover for the past four years. They seized the upper hand in the victorious battle of Weimar, and from there the South Germans gradually occupied large parts of Hannover. By January of 1885, the Bavarians were in Hanover, with the decrepit King August-Wilhelm having fled to Smolensk months before.

The Russians offered to host peace talks, and over a series of meetings in Smolensk, a treaty was slowly drawn up. Hannover was forced to cede Minden and Göttingen to the Duke of Franconia, renounce any claims over Eastphalia, disband his standing army and pay heavy war indemnities to München.

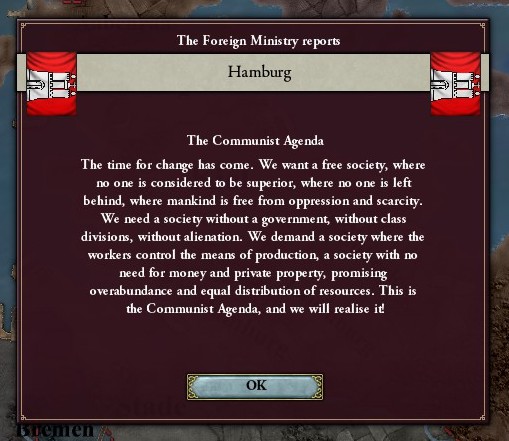

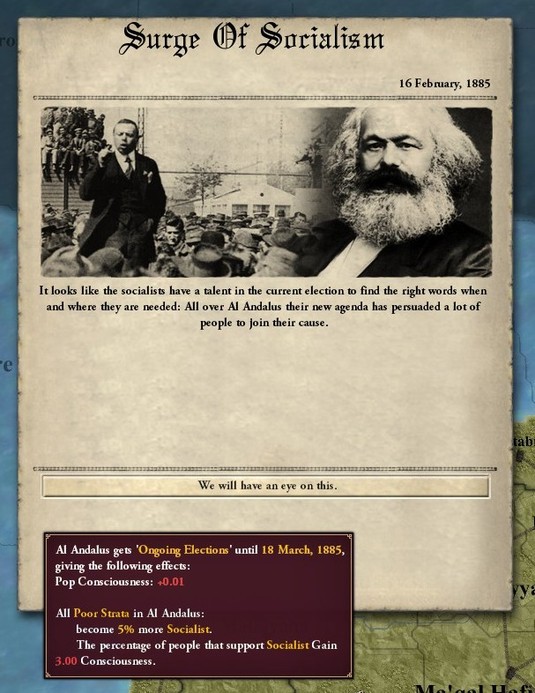

Needless to say, after almost five years of brutal occupation, vast swathes of north Germany were in turmoil and upheaval. The population had suffered for decades now, losing countless wars to France and Bavaria, fleeing the merciless sackings of enemy armies, enduring rising unemployment and rampant inflation - only to be brutally suppressed whenever they dared speak against the ruling class.

As the aristocrats of north Germany would soon learn, however, this constant oppression would only further radicalise their populace. And the peasants, labourers, workers and soldiers already had their rallying cry, defiantly shouting the words of a prominent radical-socialist, words that called for the outbreak of class warfare, for the overthrow of the bourgeoise, for the empowerment of the proletariat and for world revolution.

And these radical ideas weren’t contained to Germany, with a revolutionary political pamphlet - the Communist Manifesto - quickly carrying them to every club, every pub and every coffeehouse in Europe, inspiring a surge of support for socialism.

Demonstrations and riots were becoming increasingly common in Iberia, and eager to capitalise on this social unrest, a fringe faction within the Socialist party issued a public statement in which they formally severed ties with the socialists and established their own faction…

The Grand Vizier retaliated without hesitation, outlawing the radical political party, ordering raids on socialist offices and imprisoning any self-professed communists.

Whilst the assembly and public of Al Andalus erupted into chaos, however, the other great powers had not been idle…

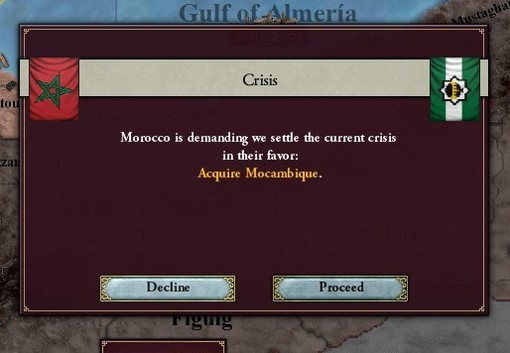

Al Andalus had not been alone in its imperialism, it would seem, with the Smolensk Conference sparking a flurry of colonial activity all across Europe. Over the past five years, the governments of Russia, Provence, Morocco, Benin and the Dual Monarchy had all launched colonial ventures of their own, carving large slices of territory from Africa.

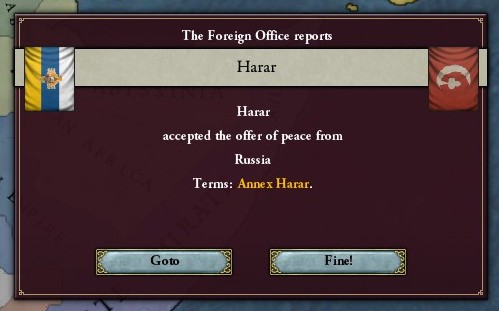

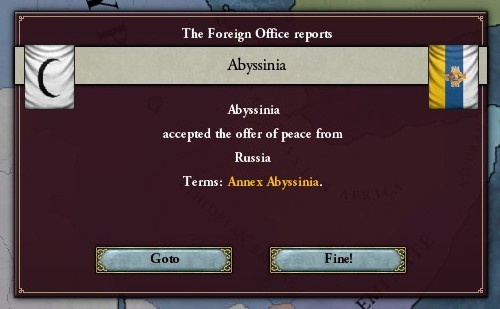

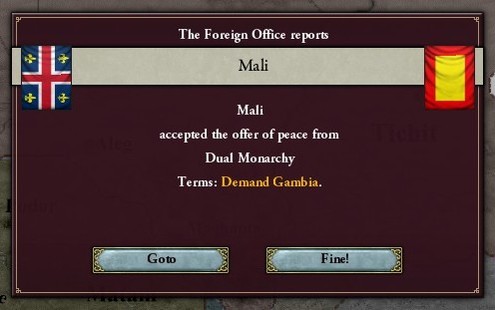

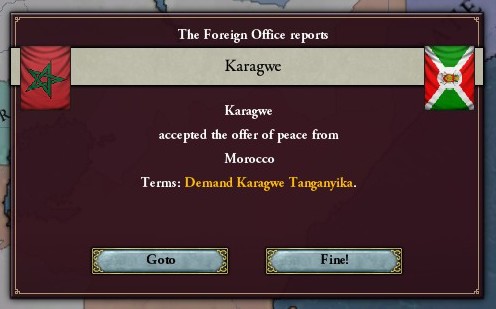

So far, Al Andalus is undoubtedly the biggest winner, with the ‘Khedive’ of the Kongo seizing the resource-rich southwestern coast of Africa largely unopposed, except for a short struggle in Cameroon. Benin was looming large to the north, with King Eweka loudly protesting the ‘foreign imperialism’ whilst desperately expanding throughout the Niger basin, with Morocco, Provence and Al Andalus gradually encroaching from the north, west and south. Egyptian expansion into Ethiopia, meanwhile, was challenged by the Russian Empire, which dispatched an army to invade Assab, Harar and Abyssinia in 1882. Further south, Morocco had rapidly expanded its holdings in eastern and southern Africa, with the Dual Monarchy finally establishing a trading post in Namibia late in 1885.

There’s no longer any doubt, the Scramble for Africa has begun.

The enormous riches and unchecked expansion in Africa made it a powder-keg for future wars, but the eyes of the world were fixed further north just then, towards the Iberian peninsula.

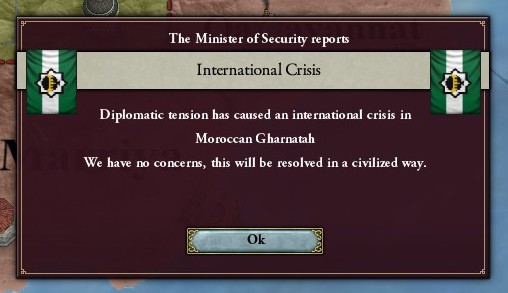

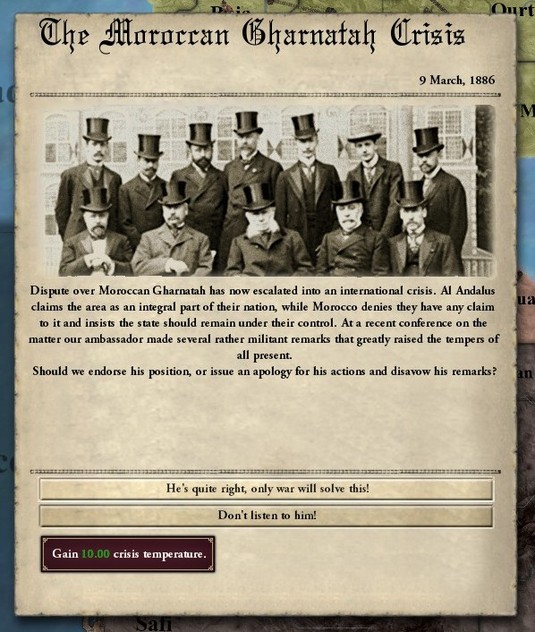

Dissidence and unrest were quickly rising, and as the Majlis al-Shura fractured into rivalled cliques, violent clashes between conservatives and radicals quickly became commonplace in the streets and alleyways of Qadis. Desperate to distract the unruly populace, Grand Vizier Murad dispatched the army to Granada early in 1886, stationing 60,000 troops a scant few miles from the Andalusi-Moroccan border.

The Berbers immediately retaliated - suspending military leave, reinforcing their garrisons in Qartayannat and Marriya, and ordering a partial mobilisation. And with the nation’s attention now transfixed on him, Grand Vizier Murad replied in kind, ordering the Iron Fleet to threateningly patrol the straits.

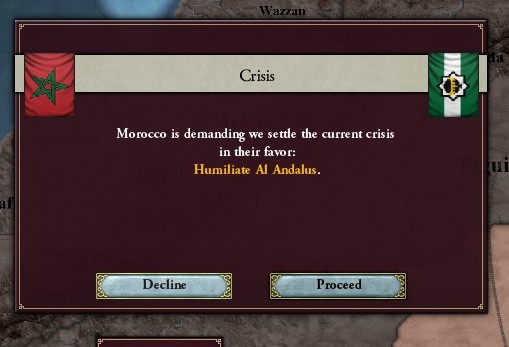

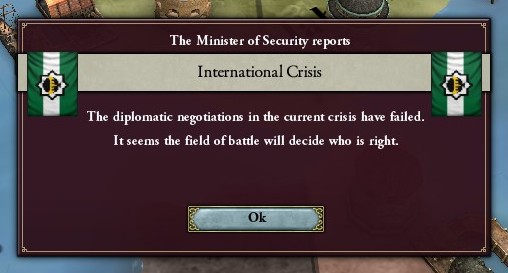

If Murad was hoping this would scare the Berbers into deescalation, then he had badly misjudged the situation. Instead, the Almoravid embassy demanded that the Andalusi withdraw from their border, warning the Majlis that war would follow if they refused to comply…

The Grand Vizier leaked these threats to the press, with the Andalusi Times immediately circulating them amongst the masses, who rallied behind the government and demanded satisfaction.

Murad’s ploy succeeded, and backed by his party and populace, he insisted that there would be no withdrawal without the surrender of Qartayannat and Marriya - rightful Andalusi territory.

On the world stage, however, Murad wasn’t nearly as convincing.

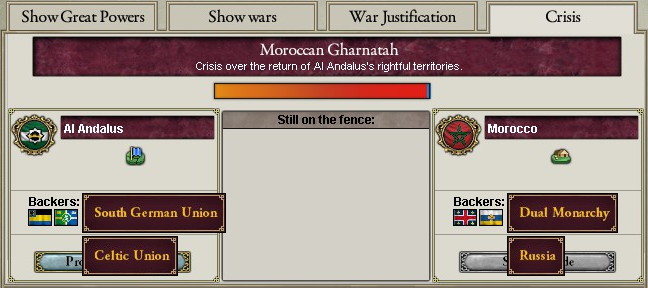

The South German Union immediately professed support for Al Andalus, but the Germans were strategic rivals to both Russia and France, who were worried by their ambitions for the complete unification of Germany. Paris and Smolensk thus declared for Morocco, hoping the crisis would escalate into war, if only to cut the South Germans down to size. And with the Dual Monarchy now opposed to Al Andalus, the Celtic Union quickly declared their backing for Iberia, determined to build on earlier victories.

Days quickly flew past, but neither Al Andalus or Morocco were willing to back down, with the two historic rivals set on a collision course. War finally arrived on the summer solstice of 1885, with Andalusi troops crossing the border and plunging Europe into war.

World map: