Part 94: The Peace of Narbuna

Chapter 14 - The Peace of Narbuna - 1890 to 1896The Continental War of 1886 to 1890 would go down in history as one of the costliest conflicts to ravage Europe yet, and with the Great Powers of Europe and North Africa all clashing for the right to dominate the old word, its sheer scale and widespread devastation was surpassed only by the Tirruni Wars. Over the course of almost five years, three million soldiers had lost their lives on the field, hundreds of thousands of civilians had fled their homes, and the balance of power in Europe was forever changed.

No single victor emerged from the Continental War, but the general consensus is that Al Andalus had the strongest claim to the spoils, having overwhelmed the Almoravid Navy on the seas, crushed the Berber and French armies on the battlefield, and seized the city of Marrakesh after a brutal year-long siege. Russian forces did eventually push them back to the Iberian peninsula, but the ensuing Treaty of Narbuna ratified their captured possessions in Qartayannat and Marriya, along with several other humiliating concessions.

And with that, as the nineteenth century draws to a close, Al Andalus reigns from the pinnacle of the world.

Wars rarely have clear-cut winners, however, especially after carnage and destruction wrought by the Continental War. And in the months that followed the armistice of 1890, it quickly became clear that the conflict would have far-reaching ramifications and consequences, well beyond the articles laid down in the Treaty of Narbuna.

The first of these repercussions was almost immediate. There had always been a steady trickle of emigrants leaving for the new world, but under the brutal years-long occupation of foreigners, this trickle quickly became a flood, so that millions of refugees had fled continental Europe by the dying days of 1889.

Millions may have fled the war, but there were still tens of millions left behind, forced to suffer ruinous sieges and devastating sackings without end. Local trade was snuffed out, food shortages became endemic, infrastructure was bombed relentlessly and civilians were forced into manual labour. And even then, the conscripts fighting on the frontlines had it even worse, facing daunting odds on land and sea alike.

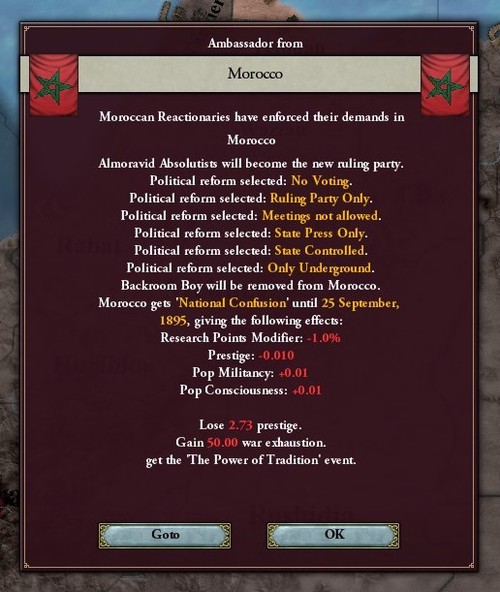

It was these disaffected soldiers who launched a series of coups and rebellions all across Europe, ignited by a reactionary revolution in Morocco, where senior officers stormed the parliament and restored absolute power to the Almoravid Sultan.

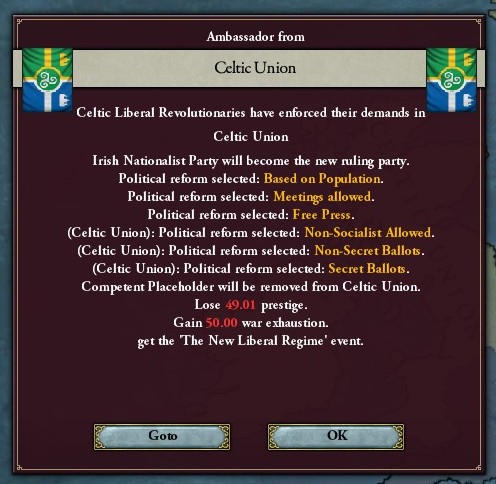

At the same time, the withdrawal of Russian forces from Ireland and Britain incited the outbreak of liberal revolts all across the islands, with hundreds of thousands of farmers, labourers and soldiers marching on government offices, burning and looting arbitrarily.

The rabble captured Dublin in November of 1890, proclaiming the abolition of monarchy and dawn of democratic government, thus bringing the 450-year rule of the ó Kildares to a violent, bloody end.

And it only got worse from there, with the wave of liberalism spreading across the width of the continent, spurring the outbreak of similar revolts. Al Andalus, Russia and France managed to quash the unrest, but an alliance of liberals and socialists toppled the despotic regimes in both Provence and Serbia.

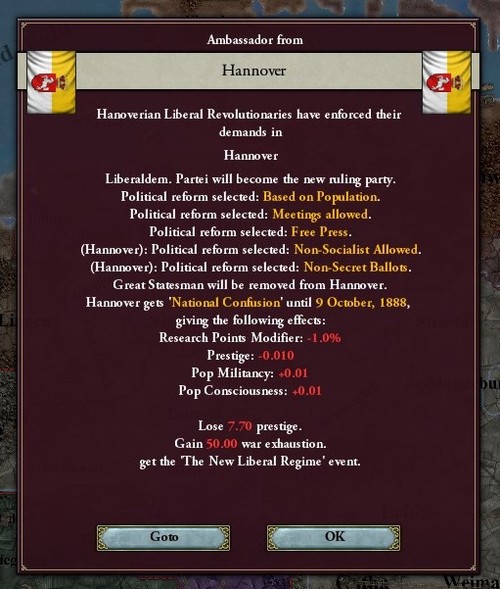

And this was quickly followed by revolution in Germany, where demonstrations had turned violent. Tensions had been escalating for decades now, with Hannover’s disastrous domestic policy, poor performance in wars and humiliating concessions to rivals giving rise to popular discontent, fuelling the widespread resentment and unrest that would eventually culminate in the Second German Revolution and the Republic of Hannover.

In their first democratic elections since the 1780s, the Germans elected a prominent populist to power, with the liberals gaining a majority in the reichstag. The new chancellor immediately began stressed the necessity of launching pre-emptive wars against the monarchies of Europe, so in the dying days of 1890, a few short hours after Christmas night, war was declared on the South German Union.

The European Exodus and the Revolutions of 1890 are both counted amongst the immediate consequences of the Peace of Narbuna, but neither truly affected Al Andalus, with the victorious kingdom instead suffering on the diplomatic front when the South German Union dissolved their alliance with Al Andalus.

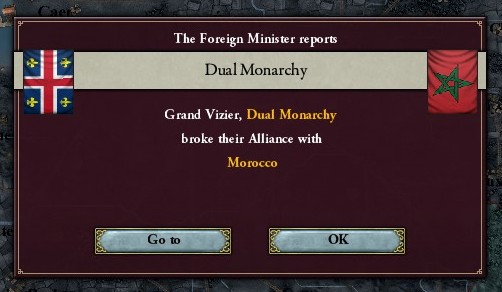

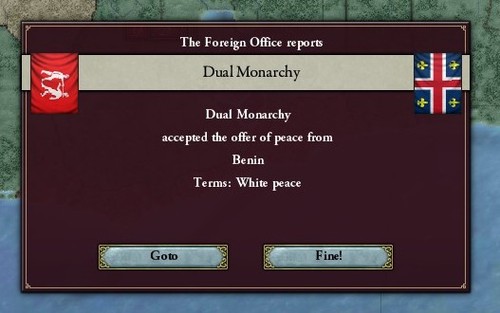

And a few weeks after war’s end, the Congressional Pact also collapsed, with the Dual Monarchy severing their alliance with the Almoravid Sultanate.

The Almoravid Sultanate immediately sent feelers out to the other European powers, striking a deal with the SGU, with the two powers signing a defensive pact later that year.

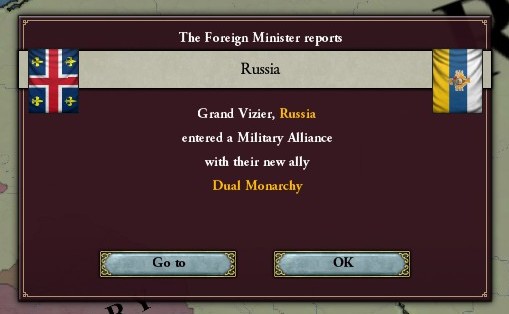

As for France, they turned eastward instead, formalising their pact with the hegemon of the east - Russia, which had ended the war on its own terms, stronger than ever.

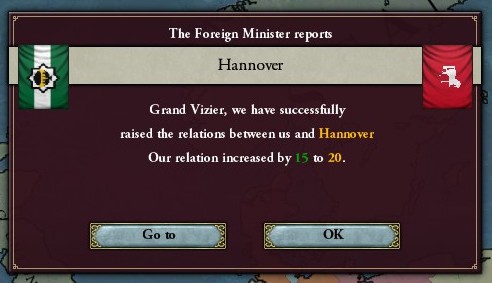

This flurry of diplomatic exchanges were over as quickly as they began, and within the space of weeks, Al Andalus found themselves diplomatically isolated in Europe. Not a great position to be in, so the Grand Vizier of Al Andalus dispatched diplomats to improve relations with the remaining great powers.

Grand Vizier Murad also had mounting crises to tackle at home, however. Al Andalus had begun the war with almost 200,000 dinars in reserve, but the conflict had proved to be far more costly than anticipated, and the Majlis was forced to withdraw expensive loans from domestic banks and foreign governments over the course of the war.

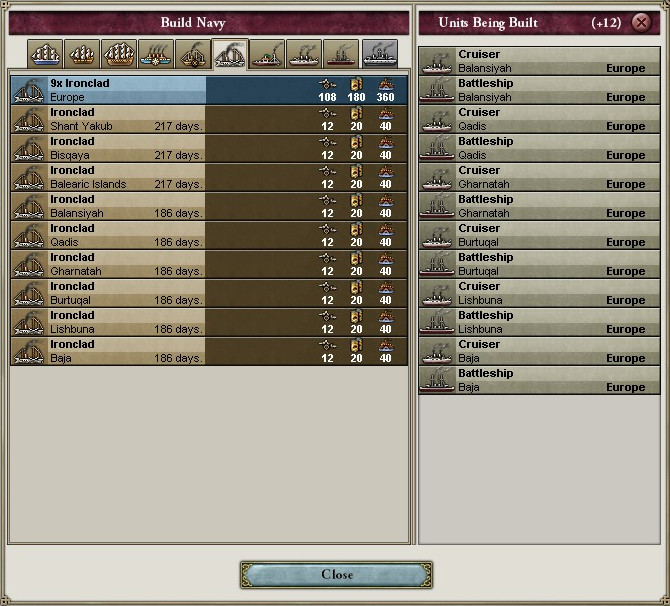

Much more important, however, was the state of the Andalusi Navy. The Iron Fleet had seized and held the straits of Gibraltar for the duration of the war, but at the cost of half its ironclads and monitors sunk, along with the vast majority of its man-o’-wars and frigates.

The importance of a navy had only been emphasised by the Continental War, so when Grand Vizier Murad presented the assembly with an expansionary bill mandating the construction of twelve new battleships and cruisers, it was quickly passed into law with little opposition.

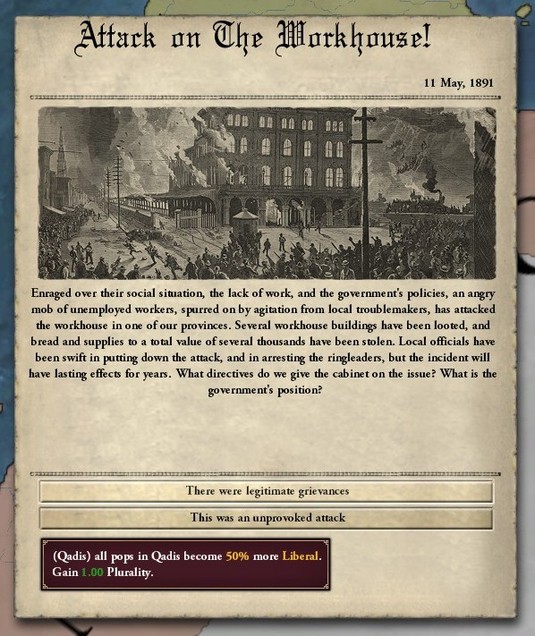

It wasn’t long before this string of successes came to an end, however, as socialism reared its ugly head yet again, with several demagogues calling for higher wages and safety standards, urging labourers to stage walkouts and strikes, and even advising workers to unionise!

This was a battle fought in busy thoroughfares and street corners of Al Andalus, and despite the blanket ban on spreading socialist ideals, these agitators launched a series of attacks on government offices and workhouses, seizing and burning thousands of dinars worth of food and supplies under cover of darkness.

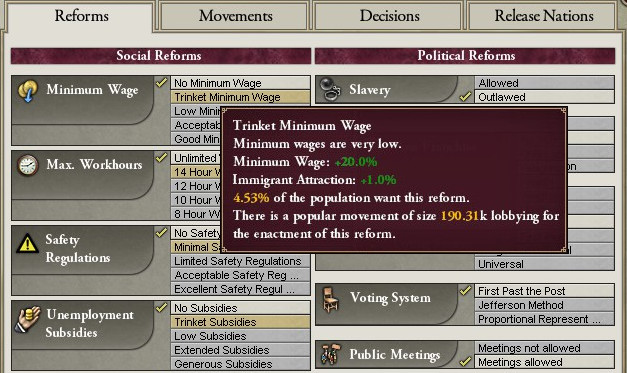

With his position becoming increasingly untenable, Grand Vizier Murad finally agreed to address the grievances faced by workers and labourers, if only to weaken the widespread popularity of socialism.

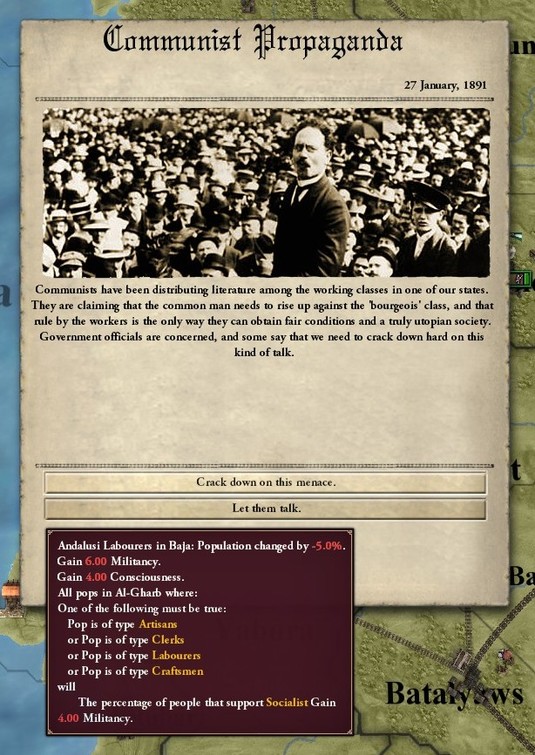

This reform only further encouraged the socialists to aim for bigger and bolder ventures, however. Before very long, communism began to gain traction amongst the lower classes, with socialist firebrands distributing communist literature, giving communist speeches and calling for communist revolution.

That was too far, and Grand Vizier Murad immediately dispatched the national guard against these rabble-rousers, whilst secretly convincing the secret police to infiltrate their organisations and syndicates.

At the same time, the great powers were quickly redirecting their resources to Africa, where explorers had begun charting the interior hinterlands of the Dark Continent for the first time in history.

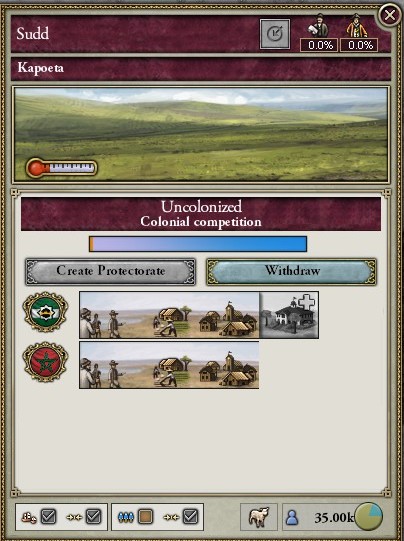

The arid desert and dense jungle of Africa were largely impenetrable, but that didn’t stop the European powers from claiming them all the same, with dozens of expeditions being launched into the sweltering tropics and drylands. The Imperialists were distracted by their expensive wars and domestic troubles, but Balanabus - who still illegally styled himself the Khedive of the Kongo - had ambitions of seizing Fashoda to the north, expanding into the lands surrounding Lake Zulfiqar, and uniting Andalusi Kongo and Mozambique by claiming the Land Corridor of Central Africa, which largely consisted of Malawai, Zimbabwe and Kilwa.

So whilst the Imperialists waged war on the home front, Balanabus began to challenge the other great powers for Africa’s interior, with the Khedive launching massive expeditions towards Sudan, Karagwe, Matobos and Botswanan, accompanied by tropical explorers, diplomats, translators, engineers, doctors, hunters, surveyors and hundreds of native mercenaries.

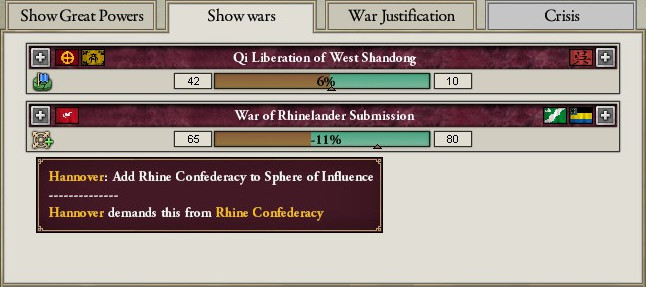

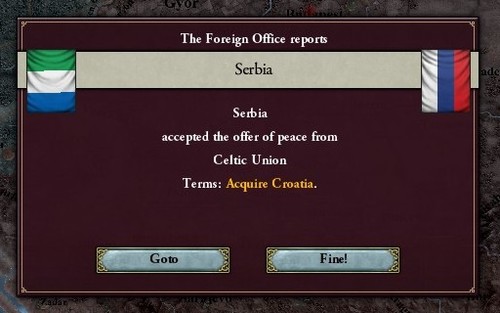

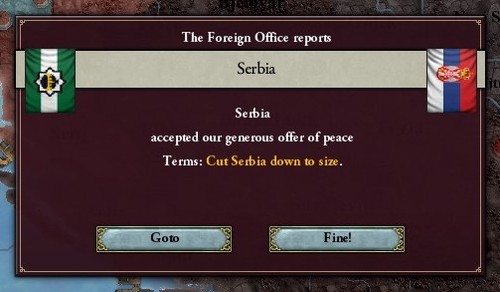

At the same time, the subsidiary conflicts borne from the Continental War had come to an end, with most of these contests ending on relatively-lenient terms.

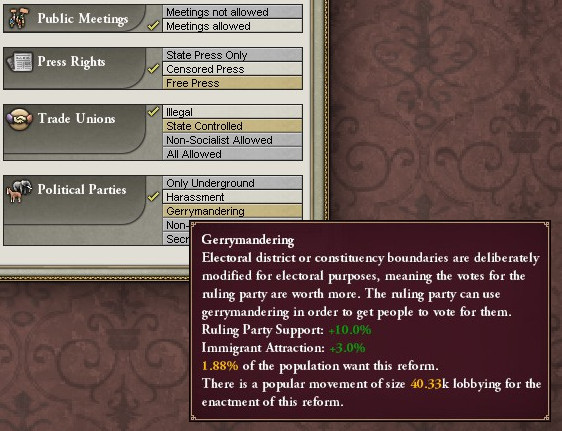

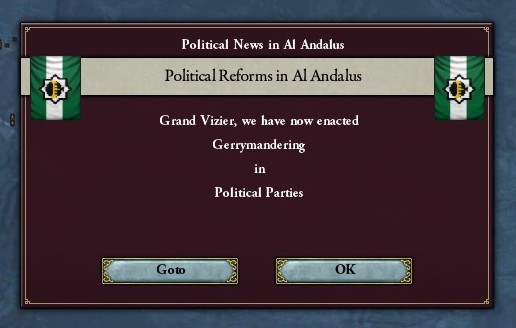

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the Majlis al-Shura had just passed another reform into law. The Imperialists had long sought to reform the political system of Al Andalus, and after vowing to weaken socialism on the masses, they managed to garner enough support to enact gerrymandering - but it also manipulated constituency boundaries so that the liberal voting base was superficially amplified.

The liberals announced the completion of the Naval Act of 1890 soon afterwards, with the strength of the Iron Fleet brought back up to a respectable 50 ships.

And with the navy finally reconstructed, the ruling party could renew their imperialist efforts abroad.

The Andalusi had conquered the Bengal Delta in 1880, but any further expansion in the subcontinent was hampered by European wars and domestic troubles. A decade later, however, the Imperialists could finally reignite their ambitions in the region, with the Indian Expeditionary Force immediately engaging a Cedi army beneath the walls of Rajbalhat - and, after a short but ferocious battle, decisively crushing them.

This was followed by another engagement a few weeks later, and the ensuing battle was just as bloody as the last. After four hours of heated battle, however, the Andalusi emerged triumphant, forcing the enemy abandon their guns and retreat en masse in another decisive victory.

With two massive armies utterly crushed, the Cedi Emperor was forced to pull back his forces and reconsider his strategy, withdrawing to Orissa for a short respite.

The Andalusi would give him no rest, however, and quickly pushed onto a forced march towards Cuttack - the capital of the Cedi Empire.

Panic quickly sweeping across his royal court, the Cedi Emperor was forced to make a decision then and there, and eventually opted to escape his capital and flee southward before the Andalusi arrived. This would prove to be a costly mistake - and his last one - as the emperor was killed in an uprising just weeks later, whilst the Andalusi managed to seize Cuttack with negligible opposition.

A boy-prince was crowned emperor just days later, but the war was a forgone conclusion by then, with the Andalusi pushing on one more campaign to completely subdue any remaining pockets of opposition.

Uprisings continued to erupt throughout the subcontinent, with three emperors crowned and deposed within a year, but the Expeditionary Force slowly and methodically occupying every city and town in the Cedi Empire.

It didn’t take long for a peacy treaty to be drawn up, with these negotiations eventually culminating in the Kolkata Agreement, whereby Al Andalus would retain all their conquests in Bihar, Bengal and Pegu, whilst the Cedi Empire maintained sovereignty in Orissa.

And as predictable as ever, the Almoravid government immediately criticised the stringent terms of the Kolkata Agreement, but they couldn’t do much more than that. Morocco was facing daunting troubles of their own, with a massive rebellion having erupted in the Berber Raj, where hundreds of thousands marched against Moroccan strongholds in an attempt to establish an independent, pan-Indian state.

Grand Vizier Murad kept a watchful eye on the rebellion, but he was also forced to divert his attentions further east, towards China.

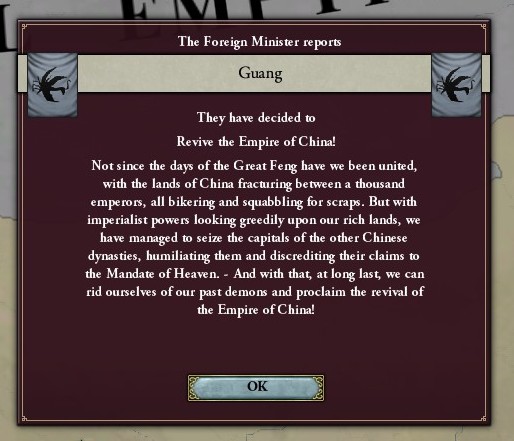

In the Land of a Thousand Emperors, the Guang dynasty had emerged as the dominant contender for the Mandate of Heaven, using their base in southern and western China to conquer the Song, invade the Qi and bloody the Wu, a series of campaigns that quickly culminated in the capture of Peking - once called Khanbaliq, the capital of the Yuan and Feng dynasties.

Ever-wary and ever-watching, the revolutionaries in Japan immediately intervened against the Guang, dispatching a number of expeditionary forces to seize Peking and force their withdrawal. Unfortunately for Japan, however, their expedition didn’t go exactly as expected.

With the help of several Western powers, the Guang had spent the past two decades desperately modernising - with new manufactories erected throughout their heartland, shipyards established along the coast of southern China and military experts invited to reform the army and navy - and by the 1890s, the Guang began counting themselves amongst the civilised nations of the world. So instead of the irregular masses they were used to fighting, the Japanese expeditionary force was faced with well-drilled, well-armed troops of a modernised army, who were able to grind the Japanese invasion into a stalemate.

For the Chinese, after six centuries of subservient rule to foreign peoples, this was hailed and celebrated as an unprecedented victory - and the Guang were quick to capitalise on it. At the height of the summer of 1895, in the Inner Court of the Forbidden Palace, the Guang formally proclaimed themselves Emperors of China, heralding the dawn of a new era in Asia.

As for Japan, well, this was a crushing defeat for them. In a culture dominated by perceived superiority and exceptionalism, the Japanese withdrawal from Peking was met with humiliation and anger, inciting the outbreak of revolts all across the country.

The blame was laid squarely at the feet of the democratically-elected shushõ, and with popular discontent quickly spreading, leading army officers managed to assassinate the shushõ and his allies in a sudden coup d’état. Within hours, the capital was captured, the government was overthrown and the opposition was dismantled, with an influential general installed as the supreme dictator of Japan.

Back in Europe, meanwhile, the French were on the offensive once again.

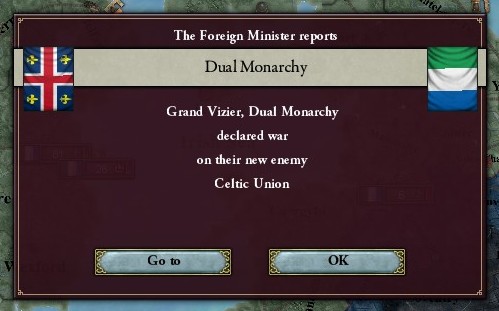

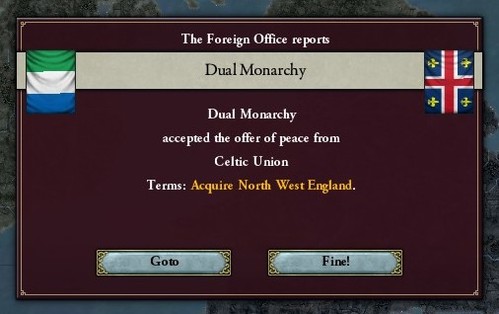

Backed by Russia, the Dual Monarchy invaded the United Republic in the spring of 1895 - fragile without allies, the United Republic didn’t stand much of a chance. And as expected, the 80,000-strong French-English army quickly crushed their conscripted levies and overwhelmed their pitiful defenses, seizing Manchester and Liverpool in the ensuing peace treaty.

Just then, however, the world's attentions were transfixed on Germany.

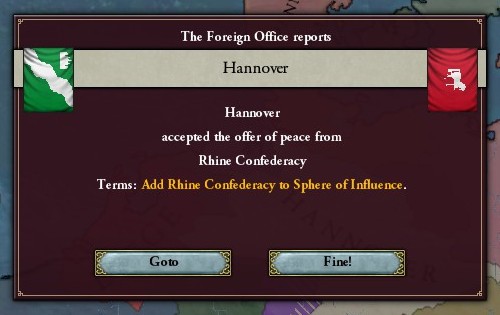

War had been raging between Hannover and Bavaria for the past five years, with the former’s undisciplined, disorderly forces well-balanced by the latter’s exhausted, mutinous conscripts. The South Germans held the upper hand early on, but republican troops managed to capture Trier in 1894, solidifying their control over the Rhine Confederacy. From there, they advanced into South Germany in the offensive of 1894, throwing hundreds of thousands into the trenches outlying München.

The city didn’t fall until August of 1895, bringing the war to an end. Archduke Karl of Bavaria quickly negotiated a peace with his enemy, surrendering his father’s hard-won influence in the Rhine to Hannover, in addition to the strategic city of Hannover. Even after the treaty was signed and dried, however, that wasn’t enough for the republicans.

A scant few days before their withdrawal from München, the Chancellor of Hannover declared the formation of the North German Republic, a confederation of the liberated principalities, duchies and kingdoms of northern Germany, rooted in liberal ideals and democratic principles.

The German Question had become more complicated than ever, and with every passing day, just as unsolvable.

Al Andalus was the first of the great powers to recognise the budding German Republic, with Grand Vizier Murad quickly establishing an embassy in Hanover, but it wasn’t long before he turned southwards - to Africa, where new imperialism was abound.

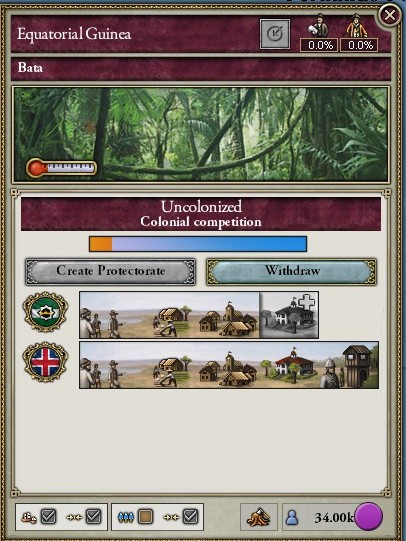

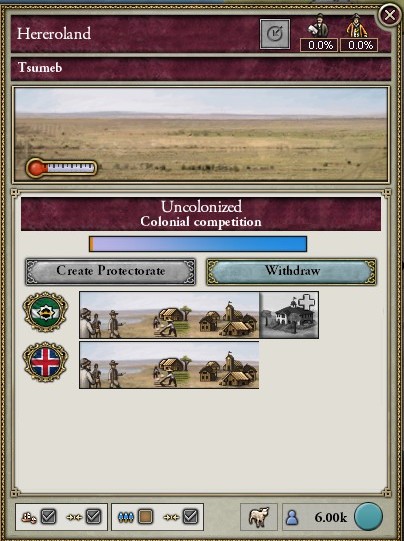

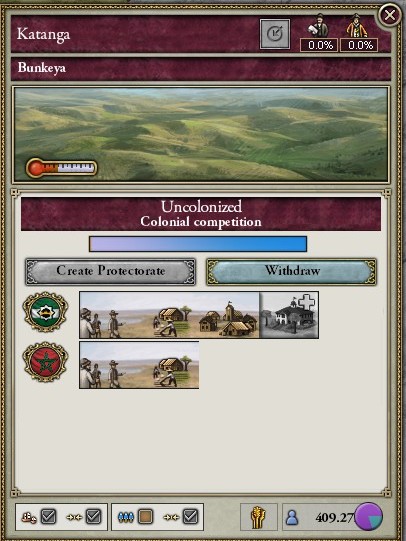

Over the past five years, the European powers had carved the last vestiges of Africa amongst themselves, with the charge led by Balanabus Min-al-Bita. The Khedive oversaw expansion towards Sudan and Karagwe, he warred and crushed the native kingdoms of Kilwa and Katanga, and he challenged Morocco for the land corridor of Central Africa.

But in the closing days of 1895, the self-proclaimed Khedive of the Kongo died, passing away in his summer palace-complex in Balbita. Within days, emissaries arrived in Qadis from his heir, with Wahb Min-al-Bita requesting that the Majlis formally recognise his succession to his father’s khedivate.

Whatever the assembly decides, few would dispute the sheer magnitude of Balanabus’ achievements, with the Khedive having single-handedly changed the face of a continent. In the earliest days of his rule, Africa had been vast and unexplored, rich and plentiful, treacherous and perilous, with native powers dominant and foreign colonialism non-existent. And now, upon his death some twenty years later, everything had changed.

Moroccan supremacy in North Africa had been shattered by the Continental War, and though they retained dominance in the Maghreb and Western Sahara, South Germany and Crusader Egypt managed to expand into Libya and Cyrenaica respectively. Egypt had also invaded the Ethiopian Empire, but their influence in the Horn of Africa was challenged by Russia, who gradually consolidated their many colonies and domains in the region under a single authority. Benin remains the only native power to successfully repel foreign invaders, and having seized large parts of the Niger basin, they now face the ambitious Provencal and Andalusi to their west and south. The Dual Monarchy had joined the scramble very late, seizing Namibia before butting heads with Al Andalus, who managed to bring the entirety of the Kongo basin under their control, as well as vast territories in Mozambique and Kilwa.

The Almoravid Sultanate of Morocco, however, had impeded and hindered the Andalusi at every turn. Upon the death of the Khedive, they capitalised on the ensuing uncertainty by enforcing protectorates on the native tribes ruling the Land Corridor of Central Africa, dividing Andalusia's African possessions in two.

The Scramble for Africa was over, but now that the colonial powers had conquered the continent, they would have to hold it.

World map: