Part 99: Opiate of the Masses

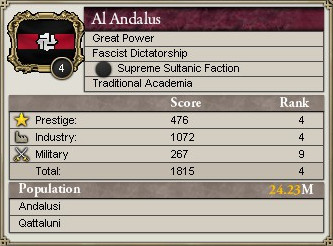

Chapter 19 - The Opiate of the Masses - 1909 to 1914By and large, the reign of the Zulfiqar dynasty had been fruitful and prosperous, bearing witness to an era of triumph unparalleled throughout the long history of Iberia. By the waning days of the nineteenth century, the Andalusi Empire stretched from Iberia to Africa to India, an economic and military behemoth that had brought an entire continent to a standstill. There was little doubt about it, Al Andalus ruled from the pinnacle of the world.

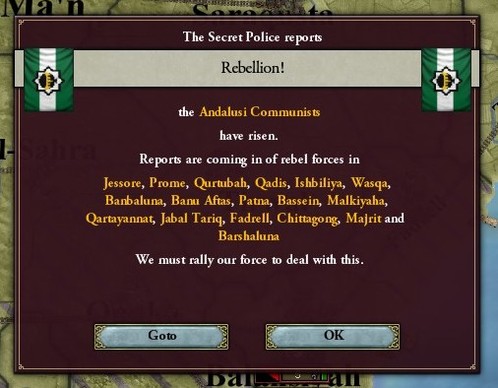

And just a decade later, everything had changed. Tensions between the left and right had cleft the country in two, riots and rampages became commonplace throughout the peninsula, demonstrations and protests were a daily occurrence and - most worryingly - rebellions were erupting all across the Andalusi Empire. Al Andalus was being challenged, and the army defending her was little more than a small, corrupt peacekeeping force, one that was scattered across the width of the globe.

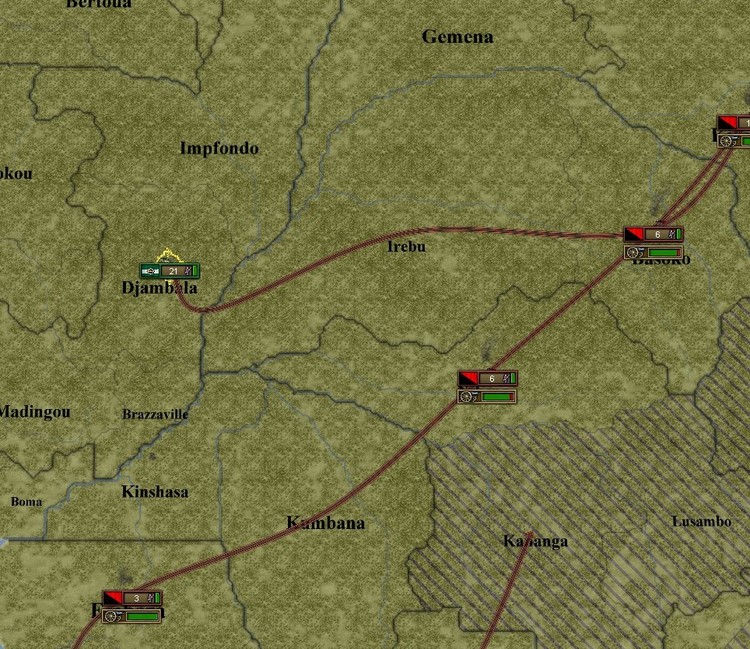

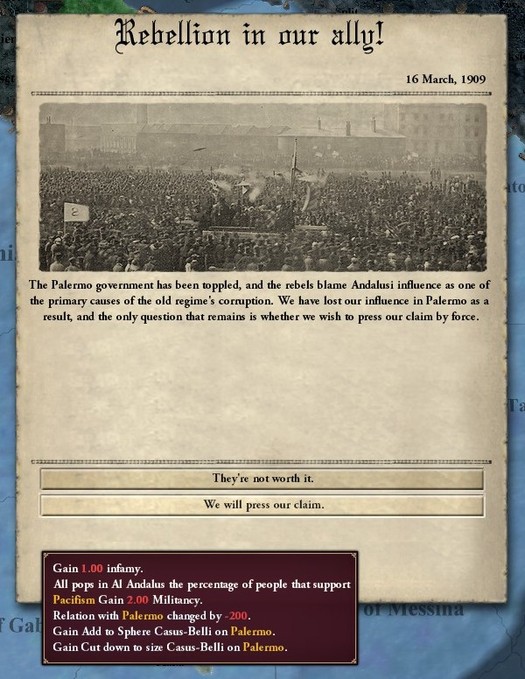

Starting close to home, there were 30,000 soldiers dedicated to quelling the rebellions in Palermo, just one of many countries to suffer a wave of revolutionary unrest after Serbia’s victory in the First Struggle…

40,000 Andalusi and African soldiers were committed to restoring order in India, where friction and hostilities were still lingering after the hard-won defeat of the Indian Uprising…

Another 25,000 soldiers were tied down in Africa, where secessionist and independence movements were quickly gathering steam…

And that left almost 70,000 soldiers to garrison and defend the Iberian peninsula. Not enough to repel an invasion from the north, but certainly sufficient to keep the peace, suppress any potential rebellions, and counter any attempted coups…

Or so it was thought.

The first decade of the twentieth century ended with the mass uprising of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese, Castilians, Qattaluni and even Andalusi, all rebels and rioters drawn the commoners and nobles, from the poor and rich, from the north and south - hundreds of thousands of revolutionaries, from every walk of life.

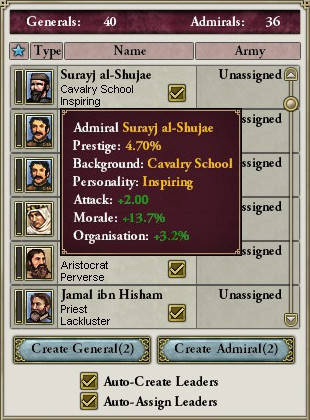

This was clearly a state of emergency, so Sultan Khuzaymah used his royal prerogative to override the aristocracy and personally appoint the new Grand Vizier. The Sultan was said to be dazed and delirious when he took to the stands, but he was surrounded by dozens of SGA agents, so nobody protested as he announced that Surayj al-Shujae would serve as his Grand Vizier. Surayj had already earned a reputation for his relentless ruthlessness during his tenure as Commander of the SGA, but his detractors and enemies had only one name for him — al-Attar. The Poisoner.

The vast majority of the rebels were Communists acting on orders from Belgrade, orders to ignite the masses, topple the government and bring the revolution to Iberia. They would not rest until Qadis was a smouldering ruin, so the new Grand Vizier immediately dispatched the army to crush them - however high their numbers climbed, these rebels were surely no match for the Andalusi Army.

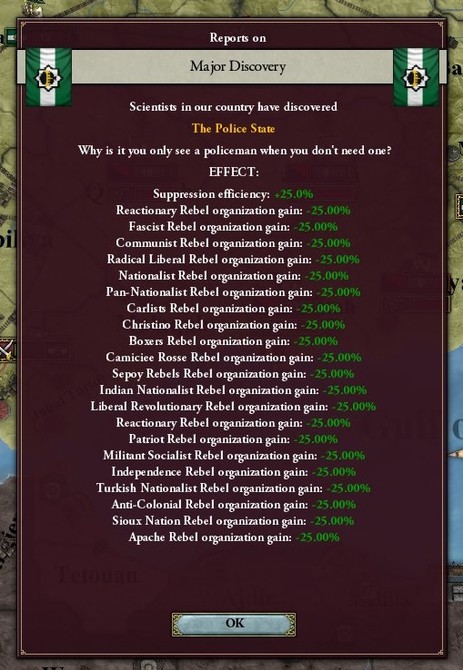

Half a million revolutionaries would certainly keep them busy, however, so it was imperative that any further rebellions be thwarted before they could begin. Acting on the Grand Vizier’s orders, the SGA thus launched a far-reaching propaganda campaign that played down the size of the rebellions, fabricated massacres and atrocities perpetrated by the revolutionaries, and blatantly discredited their leadership.

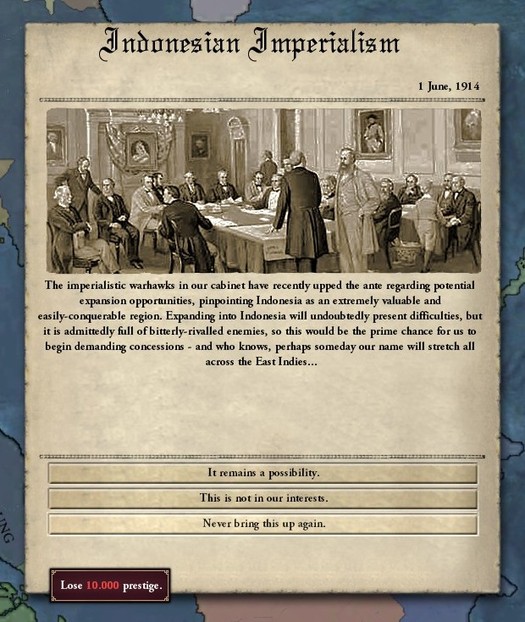

There were some within the government who even proposed that Al Andalus declare war on some Indonesian minor, in a half-hearted attempt to distract the general public from the problems at home. These suggestions were immediately shot down by Grand Vizier Surayj, of course. The army had enough to deal with as it was.

The same could not be said for Andalusia’s rivals, however. The Dual Monarchy, in particular, was thriving, with a populace that was largely united under their banners of constitutionalism and monarchism. The lack of internal troubles had allowed the Dual Monarchy to continue their imperialistic adventures abroad, with a series of unequal treaties and harsh peaces drawn up and signed over the course of the 1910s.

And they weren’t the only great power with interests in Indonesia. After their crushing defeat in the Continental War, the Sultanate of Morocco had regressed into absolutism once more, but Sultan Ajjedig used his powers to great effect, cracking down on corruption and issuing a series of expansionary laws that quickly brought his army and navy back to par. To add to that, the Sultan managed to negotiate a tripartite pact that reunited Morocco, Russia and the Dual Monarchy into their powerful alliance bloc - the Congressional Coalition.

In an effort to improve relations between the newly-allied powers, emissaries from Paris and Marrakesh had been negotiating a partition of Indonesia over the past few months, with lines arbitrarily drawn through Sumatra and Borneo, divvying the richly-populated islands between the two powers.

The Congressional Coalition was not completely unchallenged, however, with their principal rivals being the dual alliance of Germany and the United Republic — both of which were democracies with long histories of defeat and occupation to the nations of the Congressional Coalition. From the moment that this democratic bloc was formed, the two republics had been growing increasingly close to one another, with joint military exercises, extensive trade agreements and alliance summits organised between Germany and Celtica.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, there was a brief respite from the carnage and havoc in the form of Zubayr - the new heir to the Sultanate of Al Andalus. Apparently, Sultan Khuzaymah had managed to stagger away from his absinthe bottles and opium pipes long enough to sire a son, but the young boy was immediately plucked from his mother’s breast and taken into custody by Grand Vizier Surayj.

The Sultan himself never even protested, it would seem. He simply went back to his usual routines, enjoying the decadent pleasures and hedonistic indulgences provided to him by his Grand Vizier, drowning and smoking his worries and troubles away in the very same palaces where Sultans had once reigned with unyielding, unchallenged authority.

Once young Zubayr was whisked to a concealed location, along with all the wetnurses and servants and tutors he could possible need, Surayj al-Shujae turned back to the fires raging across the peninsula.

Al Andalus had been flourishing in recent years, but with the outbreak of clashes and fighting throughout the country, the rule of law disintegrated and famine swept across the peninsula. Starving commoners joined the revolutionaries in the streets and alleyways, calling for bread and clothes for themselves and their families. And when their pleas went unanswered, they joined the radicals and revolutionaries in calling for strikes, mutinies and anarchy instead. Trickling down from the north, all of these disaffected and disenfranchised commoners had one voice, shouting one thing: “The people will prevail!”

That rallying cry was promptly outlawed by the Grand Vizier, though he couldn’t actually do much to enforce that ban. The factory workers and miners yelling those words weren’t the real threat anyways, no, the real threat was in the north — where the radicals were gathered, trained and given guns, turning them into soldiers.

The Andalusi Army marched on these rebel armies whenever they drifted too far south, of course, with decisive battles fought at Majrit, Safra and Madinat Zaytuna. The farthest they had reached was Qurtubah, where the rebel attack coincided with mass uprisings in the city, forcing the Andalusi army to simultaneously repel the revolutionaries and suppress the rioters in brutal fashion. Needless to say, the holy city was bathed in blood during those long hours.

But it was to little avail, because the rebels just kept coming. In fact, it only seemed to be getting worse, with the trickle widening into a stream, the stream into a river and the river into an almighty flood. To finally stem the tide, Grand Vizier Surayj knew that he would have to march on the rebel stronghold, but that would almost certainly galvanise the northern governorates against him, transforming this petty uprising into a full-blown civil war.

No, that had to be avoided, at any cost.

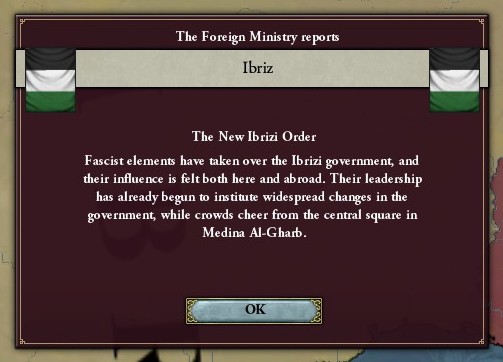

Whilst the fighting intensified in Iberia, the very same was happening across the vast and restless ocean, in Andalusia’s long-lost son — Ibriz.

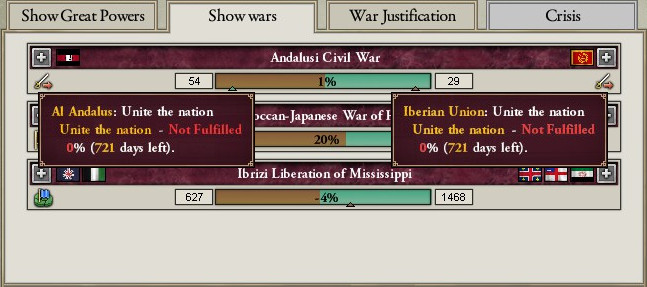

Ibriz had been hit hard by their defeat to New England, forced to pay massive reparations in addition to ceding vast swathes of land, surrendering everything east of the Mississippi to their longtime rivals. Needless to say, these punitive peace terms led to a surge of discontent in Ibriz, discontent that culminated in a bloody coup d’état that overthrew the democratic government, toppled the ruling oligarchs and brought a new order to power…

In a terrifying series of sweeping laws, complete power and authority was centralised around a single man, an ambitious politician who promised to turn his grand visions of Ibrizi ascendancy and supremacy into reality. Their surrendered territories would be retaken, those responsible for the treaty would be crucified, and the lives that had been lost on the bloody banks of the Mississippi would be repaid a thousandfold.

This new dictator was no fool, however, and immediately began seeking allies. When his overtures to Al Andalus were rebuffed, he turned to the sprawling empire of Japan instead, another nation that was led by a martial dictator…

And with economic and material assistance from their his new allies, the dictator of Ibriz launched a series of ambitious public projects in an effort to win the support of the masses, starting with the long-awaited completion of the Panama Canal — a daunting venture that been foiled multiple times on account of economic woes, internal troubles and disastrous wars.

Japan, meanwhile, were looking to gain something from this new alliance as well. Ever since the stalemate during the last Japanese-Chinese war, the former had been earnestly expanding their arsenals on land and sea, determined to storm to victory when tensions next exploded into a hail of bullets and gas.

And at long last, that time had come, and there would be no conditions or stipulations this time. This time, the shushõ of Japan made a single demand — that the Emperor of China submit to him, unconditionally and irrevocably, surrendering his crown and capitulating without a fight. The Emperor’s response was unsurprising.

The shushõ of Japan had been expecting his longtime enemies to decline, of course, giving him the perfect pretext for war. What he didn’t count on, however, was the possibility of the other Great Powers intervening against him. And that’s precisely what happened, with Almoravid Morocco declaring war on Japan a scant few days after hostilities erupted in East Asia.

The Berbers claimed that they were simply honouring a secret alliance between them and China, but the more skeptical questioned these motives. After all, it was common knowledge that the Berbers desired complete domination over the Indian subcontinent, and Japan was the largest obstacle to that ambition…

There were scarcely any who protested as African guns made their way across the Indian Ocean and into the hands of Indian conscripts, however, and the few dissenting voices were quickly silenced when the full might of the Russian Empire and the Dual Monarchy threw their lot into the conflict as well. All of the sudden, Japan was at war with half the world.

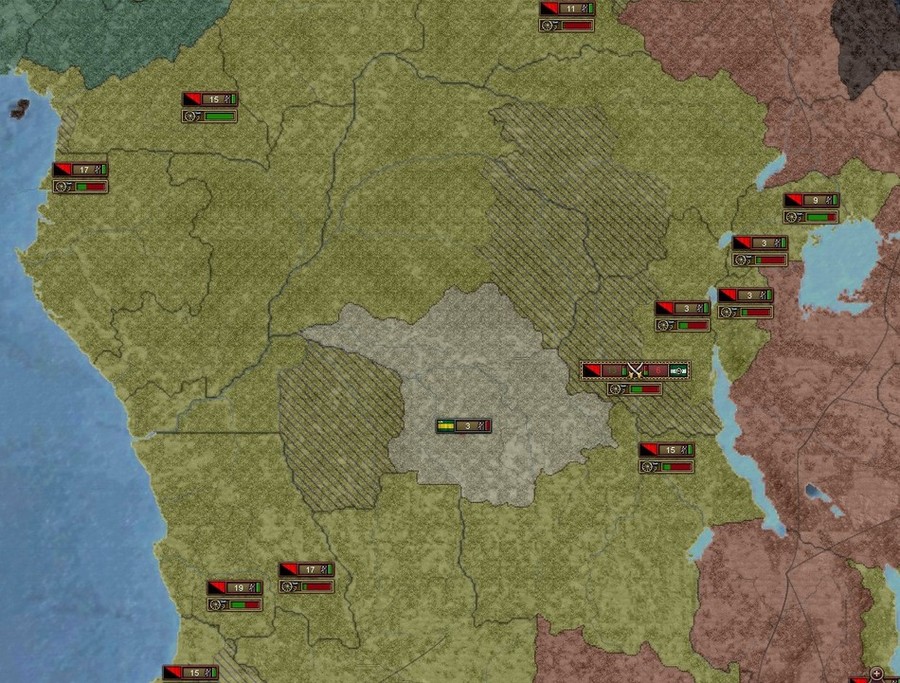

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, rebellions and revolts continued to sprout across the width of the peninsula. The Andalusi army had performed admirably in maintaining government control over southern Iberia, but its strength had been whittled down to a measly 30,000 soldiers, all weary and wounded and ill-equipped.

In contrast, the revolutionaries had only grown stronger, with two armies numbering 100,000 apiece gradually pushing southwards, almost entirely composed of veteran troops, with countless volunteers and fanatics following in their wake. The leadership of these militias was strengthened by dozens of defecting generals and commanders, having grown disillusioned with the rule of Grand Vizier Surayj and his ferocious lapdogs. Despite the Black Vizier’s best efforts, this crisis was beginning to spiral out of control.

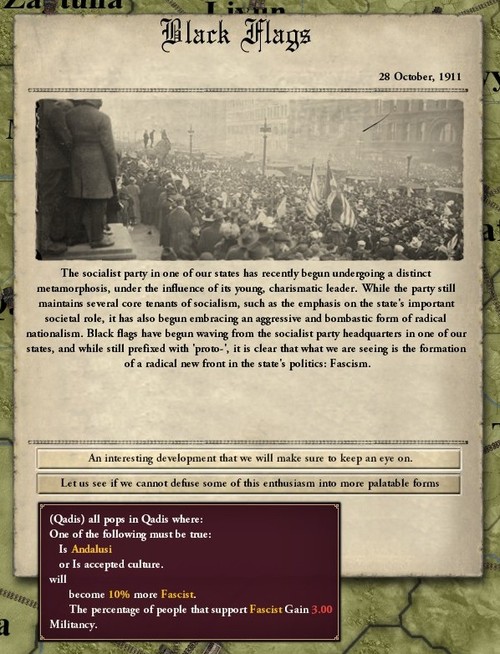

So Grand Vizier Surayj turned to his own strengths instead, calling upon the loyalists and royalists in the general public to defend their cities and homes against the invading radicals. SGA agents were deployed to highly-populated cities throughout Iberia, where they delivered impassioned speeches and whipped the crowds into a frenzy, waving black flags and promising retribution against the rebels.

The masses were not very responsive at first, but truckloads of food and supplies began pouring into those same cities before long, bearing the black device of the SGA.

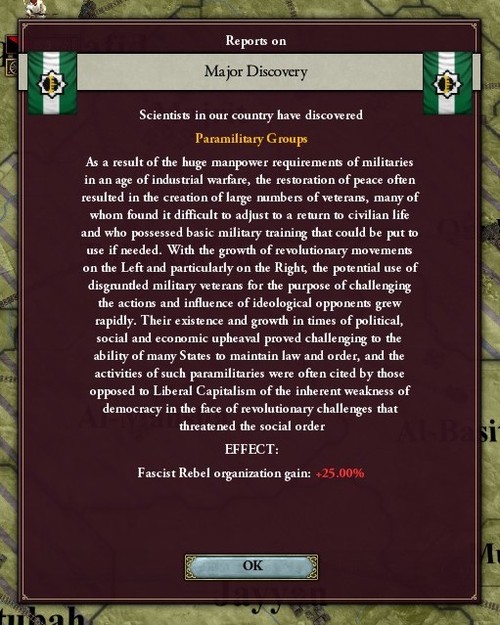

And with that, the commoners quickly began to answer the summonings of the Grand Vizier. Under the supervision of his most trusted agents, paramilitary corps were founded in cities throughout Al Andalus, with thousands of green volunteers drawn from Qadis, Ishbiliya, Qurtubah and other cities dotting southern Iberia, trained in guerilla-style tactics and garbed in black uniforms.

These blackshirts rapidly grew in strength in the months and years that followed, swelling from a few hundred to thousands, and from thousands to tens of thousands, tens of thousands of soldiers who were utterly devoted to countering the advance of the radical scum.

This was when the Black Vizier made his move.

In the dead of night, deep into the winter of 1913, a small number of veteran soldiers quickly and quietly secured control over the administrative and political centres of Al Andalus — the Zulfiqar Palace and the Majlis Assembly. At the same time, lone gunmen slipped across the city unseen, stealing into the homes and residences of several prominent viziers and sheikhs. And lastly, thousands of manifestos and pamphlets were distributed throughout the capital, pamphlets that declared the end of the rule of the Majlis, and the restoration of power to the Sultan.

By the time the sun dawned on Qadis, it was already over. Sultan Khuzaymah had been secured and imprisoned “for his own wellbeing”, along with an ample supply of opium. Large parts of the Reformed Socialist and Imperialist leadership were dead or dying, with the few survivors escaping the city and fleeing into exile. And the Grand Vizier himself was declared the regent incumbent of Al Andalus, the chief advisor to the monarch, the sole protector of the realm. Surayj al-Shujae had effectively declared himself the Autocrat.

The pamphlets distributed to the commoners did little to calm the tensions in the streets and alleyways of Qadis, where riots and clashes continued to spontaneously erupt between rebels and government officials. Determined to restore order in the capital, Surayj deployed his paramilitary forces against any resistors, with the blackshirts mobbing and killing anyone who dared speak against the Sultan or his poisoner. And before long, the black flag of the SGA was flying alongside the crowned pomegranate of Al Andalus, all but legitimising the coup d’état.

Once peace was forced on the capital, Surayj could turn his attentions back to the north, where the revolutionaries were gradually gaining ground on the army. If he was going to reverse their mounting victories, then he would need more bodies to overwhelm their sheer numbers, so the Black Vizier ordered a mobilisation of the general population — the first mobilisation since the outbreak of the Continental War.

And whilst boys were being pulled from their families and thrust into battles, the Andalusi armies deployed abroad were recalled to Iberia, once again on the orders of the Grand Vizier. There were no liberals or moderates who dared oppose his commands now, so the Indian Expeditionary Force were pulled from their station, leaving their hard-won peace to fragment and crumble behind them.

The same was done in Palermo, with 23,000 Andalusi soldiers evacuating the island and leaving the emirate to tackle their communist and liberal rebellions alone.

And in what could hardly be described as a surprise, the monarchy in Palermo quickly collapsed after the Andalusi withdrawal. As left-wing revolutionaries descended from the north, tens of thousands of workers rose up in Palermo’s largest uprising yet, with the starving rioters and firebrands defeating loyalist forces in a series of vicious street battles, forcing their way into the royal palaces and mansions, and stringing up the Jizrunid Emir in a messy, barbaric execution, quickly followed by his wives and children.

Grand Vizier Surayj didn’t care much, however, he needed all the soldiers he could get his hands on. Restoring the monarchy in Palermo could come later, there was always another Jizrunid to drag up and install onto the throne.

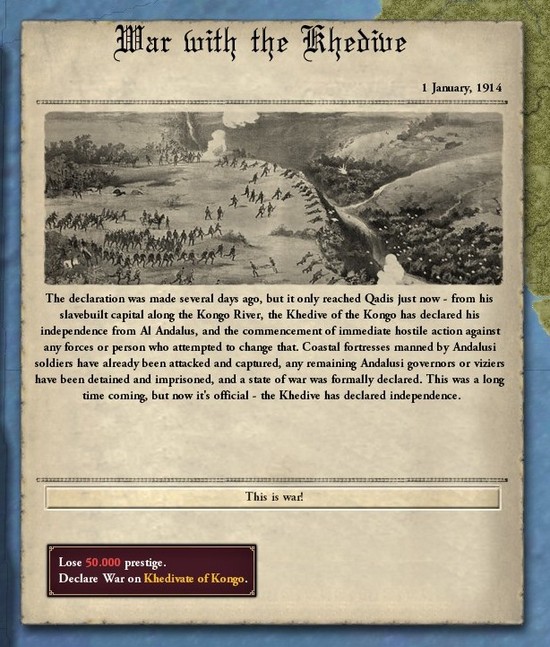

So similar orders were relayed to Africa, with the expeditionary forces stationed there ordered to march to coastal harbours, along with several thousand colonial troops. This time, however, it would not be so easy…

Whilst the Andalusi forces were making their way westward, marching on well-trodden routes along the southern forests and woodlands, tens of thousands of screaming soldiers came surging out of the murky depths and towards the Andalusi army, falling on them from every direction.

The commanding general managed to piece together a defensive line, but the ensuing battle could only be described as a massacre, with the Andalusi army wiped out in its entirety. And it would only get worse in the days that followed, with Andalusi fortresses captured and garrisoned, with Andalusi artillery and warships seized, with Andalusi diplomats and citizens detained.

And the Khedive of the Kongo — Wahb Min-al-Bita — was behind it all, formally declaring war a number of weeks later, before calling on his allies and correspondents in Morocco, Egypt and Japan to aid him in dealing an almighty blow onto Al Andalus.

Morocco and Japan were quite busy just then, however, with the two powers embroiled in a brutal war that was raging across the width of Asia. And nowhere were the battles bigger and bloodier than in India, where hundreds of thousands of conscripts clashed in dozens of engagements and campaigns that stretched from one end of the subcontinent to the other.

Japanese forces had initially made substantial gains into Moroccan India, even reaching the Deccan Plateau on the particularly-aggressive winter offensive of 1912, but they were always pushed back across the border by Berber troops. And much more gradually, the Berbers advanced into Japanese territories, crossing the Mahi River late in 1912, then the Luni River four months later, and finally the great Indus River in the dying days of 1913.

By year’s end, it had become clear that Japan had lost the war in India.

And little better could be said for the war in East Asia, where Russian forces had conducted one of the largest offensives in modern history. 70,000 Russians battled almost 120,000 Japanese soldiers in the humid heat of the Manchurian summer, seizing a series of decisive victories as the over-confident and under-equipped Japanese troops were forced to hastily retreat, surrendering city after city and abandoning vast swathes of richly-populated, immensely-fertile land to the enemy.

Finally, as the new year dawned on Japan, the home islands themselves came under threat. Russian leadership decided against invading the islands, as did the Moroccans, but telegrams and broadcasts were sent to the Japanese government with warnings to surrender unconditionally, or else suffer a fate far worse.

And with their armies crushed and morale shattered, the shushõ could do little but comply.

The fighting ended with the signing of an armistice in the early days of 1914, but the war would not formally come to a close for several months yet, with the victorious powers immediately diving into a series of meetings, negotiations, arguments and conciliations and settlements in an attempt to reach a peace that satisfied them all.

The papers were finally signed and dusted almost seven months later, with the grand premier of Japan personally ending the devastating conflict with a quick scribble of his name — and that would be his last action as shushõ, with the dictator assassinated by ultranationalists just four days later.

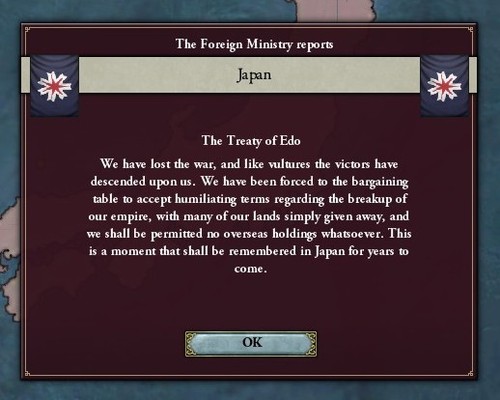

In addition to immense reparations and indemnities paid to each of the victors, the Treaty of Edo effectively dismantled the overseas empire of Japan. Starting with their vast possessions in India, the Almoravids finally achieved their long-sought ambition of dominance in the subcontinent by seizing Gujarat and Rajasthan, whilst Russia managed to subjugate the agrarian and naval beacon of Sindh.

Most of Russia’s battles were fought in Manchuria, however, and they used the leverage won in these battles to annex immense tracts of Siberia, Kamchatka, Primorskaya and Sakhalin into their empire. And in an effort to secure their influence in East Asia, they managed to convince the other Great Powers to create an independent nation in Manchuria, finally freed from the oppression and tyranny of the Japanese revolutionaries.

Japan was left frenzied and scathing, having been humiliated on land and sea alike, stripped of their richest and most valuable possessions, and left to lick their wounds whilst foreigners carved their empire amongst themselves — even the tiny island of Jeju, one of Japan’s oldest conquests, had been brazenly ripped away from them.

This peace would not be allowed to stand. It might survive a year, a decade, even a lifetime, but it would be challenged and reversed eventually, and its authors would be given the exact same treatment when their time came.

The Revolutionary Republic of Japan would have to bear through difficult days before then, however. The Treaty of Edo would become renowned for its carthaginian terms and draconian clauses, utterly inscrutable and infamously ruthless — and perhaps most importantly, it was the model on which all future treaties were founded. An ominous sign of things to come.

For now, however, the Great Powers were victorious, and they could turn their attentions closer to home - or, more precisely, towards Iberia.

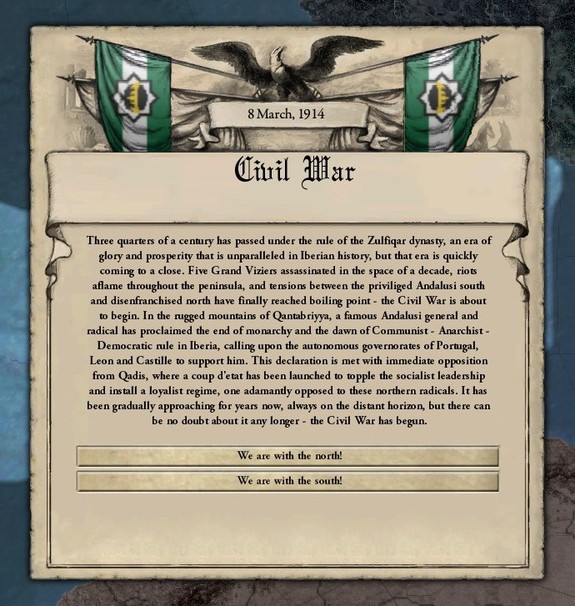

Despite delivering intimidating speeches and colourful threats, despite ordering countless kidnappings and political assassinations, despite battling fervently in assemblies and battlefields alike, Grand Vizier Surayj watched as his nation gradually slid towards the fearful spectre of civil war. Tensions between loyalists and radicals threatened to erupt into full-fledged battles throughout the country, all they needed now was a spark, a spark that would set the entire peninsula afire, a spark that finally arrived in the autumn of 1914…

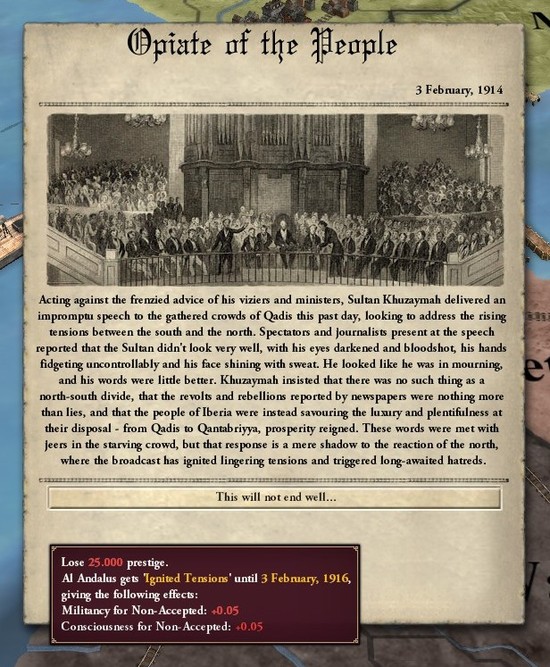

Sultan Khuzaymah, to the surprise of his courtiers and horror of his advisors, had decided to deliver an impromptu speech to the people of Al Andalus. He looked like a demon and spoke like a maniac, and his voice was broadcasted across the width of Iberia, with the Sultan vowing to root out the traitors who stole his son, promising to crush the radicals and revolutionaries who threatened his rule, pledging to lay waste to all those who dared to oppose him.

That speech and those words were the final blow, a blow that cracked the peninsula in two.

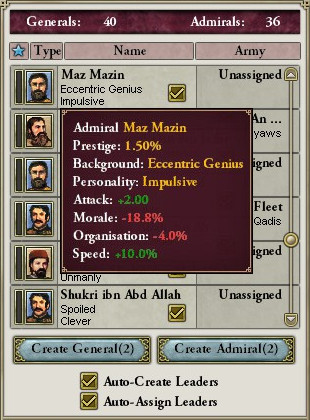

From his hidden fortress in the rugged mountains of Qantabriyya, the driving force behind the revolutionary movement finally revealed himself — Maz Mazin, simply called Rais or Leader by his followers, countered by delivering a speech of his own, one that was relayed into every home and factory and palace in the peninsula…

It was time for the proletariat to finally break the chains that shackled them to the distant past and abhorrent present, Maz Mazin screamed. It was time for them to look to a better future, one where they didn’t slave away in factories for all hours of the day, one where they weren’t subject to the whims and desire and pompous nobles, one where they didn’t live in fear of abduction or assassination. Or, to put it simply, one where they didn’t suffer under the neglectful rule of the Majlis and the Sultan.

The speech was short and effective, and Maz Mazin closed it with a phrase that would reverberate for decades afterward — “The people will prevail!”

All that was left now was for the people to decide where their loyalties lay, and what they were willing to die for.

World map: