Part 2: November 5 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be playing Beethoven’s 5th symphony in preparation for an hour long documentary on the great musician which will be after the news. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. Next week, we will be presenting a special on the international spy games being held in Zurich comparing the intelligence officers of over 30 nations worldwide. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the second part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last segment, we discussed the conspiracy to divide the French forces, to garner many allies to march on Paris, and the disembarkation of the Dutch militia to the English channel with which they would invade Paris.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the second part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last segment, we discussed the conspiracy to divide the French forces, to garner many allies to march on Paris, and the disembarkation of the Dutch militia to the English channel with which they would invade Paris.

France in a strong defensive position for the impending invasion at sea, but poorly garrisoned in Paris on land.

The Dutch had set sail in their heavily armed ships. Two fifth rate warships accompanied by several escorts made their way to the English Channel, currently held by the French. Here would be one of the most crucial naval battles of the eighteenth century. The French, with 7 ships against 5, with three of their ships being rated frigates compared to the two Dutch frigates, were at a considerable advantage. Escorting the barges carrying the invading Dutch militia from the North to Center of the English Channel, the Dutch fleet needed to clear not only the French channel fleet, but also their garrisoned fleet stationed at Le Havre. Outgunned, the Dutch would have to outwit the French channel fleet if they had any hope of invading Paris. If they failed, the French would pursue them, sink their fleet, and kill the entire Amsterdam militia. This was the Battle of Le Havre, also known as the Battle of the Eastern Channel.

The Dutch had set sail in their heavily armed ships. Two fifth rate warships accompanied by several escorts made their way to the English Channel, currently held by the French. Here would be one of the most crucial naval battles of the eighteenth century. The French, with 7 ships against 5, with three of their ships being rated frigates compared to the two Dutch frigates, were at a considerable advantage. Escorting the barges carrying the invading Dutch militia from the North to Center of the English Channel, the Dutch fleet needed to clear not only the French channel fleet, but also their garrisoned fleet stationed at Le Havre. Outgunned, the Dutch would have to outwit the French channel fleet if they had any hope of invading Paris. If they failed, the French would pursue them, sink their fleet, and kill the entire Amsterdam militia. This was the Battle of Le Havre, also known as the Battle of the Eastern Channel.

Dutch ships moving out to fight in the Battle of the Eastern Channel.

The leader of the Dutch fleet was Lieutenant Admiral Philips van Almonde. The son of a wealthy businessman, Pieter Jansz van Almonde and long time officer of the Dutch Navy, the aged van Almonde was a veteran of countless successful actions against the French navy. Most famous prior to this battle for his contributions during the 9 years war, the battle of Le Havre would be pivotal in perpetually assuring Dutch dominance in the Atlantic.

The leader of the Dutch fleet was Lieutenant Admiral Philips van Almonde. The son of a wealthy businessman, Pieter Jansz van Almonde and long time officer of the Dutch Navy, the aged van Almonde was a veteran of countless successful actions against the French navy. Most famous prior to this battle for his contributions during the 9 years war, the battle of Le Havre would be pivotal in perpetually assuring Dutch dominance in the Atlantic.

Philips van Almonde, Admiral of the Dutch Atlantic fleet.

Against him was the Marquis of Chateaurenault, Vice Admiral Francois Louis de Rousselet. Similar to van Almonde, Rousselet was a veteran of the 9 years war, and had won several victories against the Dutch. Having ousted the Anglo-Dutch alliance at Beachy Head and Lagos only a decade prior, he was an ideal pick against van Almonde.

Against him was the Marquis of Chateaurenault, Vice Admiral Francois Louis de Rousselet. Similar to van Almonde, Rousselet was a veteran of the 9 years war, and had won several victories against the Dutch. Having ousted the Anglo-Dutch alliance at Beachy Head and Lagos only a decade prior, he was an ideal pick against van Almonde.

Marquis Chateaurenault

Departing from Rotterdam in the chill of November, the fleet was cleared for action November 16th, 1702, meeting the French channel fleet by midday. Unprepared and separated from their support at Le Havre the French attempted to regroup south west of their starting position. The Dutch sprinted forward directly west cutting nearly into the wind. The small sloop, the Burk van Alkmar set about harassing the French fleet, firing chained shot into their sails, cutting apart rigging and sail alike. The French fleet pushing back into the easterly wind, were gradually losing speed due to the speedy 18 gun boat shredding their sails and were agitated into a hasty pursuit.

Departing from Rotterdam in the chill of November, the fleet was cleared for action November 16th, 1702, meeting the French channel fleet by midday. Unprepared and separated from their support at Le Havre the French attempted to regroup south west of their starting position. The Dutch sprinted forward directly west cutting nearly into the wind. The small sloop, the Burk van Alkmar set about harassing the French fleet, firing chained shot into their sails, cutting apart rigging and sail alike. The French fleet pushing back into the easterly wind, were gradually losing speed due to the speedy 18 gun boat shredding their sails and were agitated into a hasty pursuit.

The French Channel Fleet moving towards their supporting ships from Le Havre

Philips had hoped for just such an event, cutting across the French fleet, with her smallest and most vulnerable ships at the fore, Philips crossed the T, forcing the supporting French ships, the Robuste, the Entrepenante and the Raileur to capitulate almost immediately, fleeing with damaged rigging out of the channel and into the Atlantic.

Philips had hoped for just such an event, cutting across the French fleet, with her smallest and most vulnerable ships at the fore, Philips crossed the T, forcing the supporting French ships, the Robuste, the Entrepenante and the Raileur to capitulate almost immediately, fleeing with damaged rigging out of the channel and into the Atlantic.

The Dutch fleet crosses the T at Le Havre.

In the ensuing close ranged cannon fight, the Dutch ships fired high into the approaching sails and managed to destroy the main mast of the French flag ship, the Spartiate. The unfortunate Admiral of the French fleet, Francois, Louise de Rouselette was crushed, reputedly by a falling crew member that he had sent into the shredded rigging to patch the failing sails. Killed early in the battle, his extensive knowledge of the Dutch, as well as his calming hand over the French navy were lost, and what should have been a wondrous victory to the French was at that moment lost. Just before his death, he had expressed his frustration that they could not close with the Dutch, and so his first Lieutenant, Sir Henry Murat, assuming he had desired a rapid engagement, issued the order for the French fleet to charge.

In the ensuing close ranged cannon fight, the Dutch ships fired high into the approaching sails and managed to destroy the main mast of the French flag ship, the Spartiate. The unfortunate Admiral of the French fleet, Francois, Louise de Rouselette was crushed, reputedly by a falling crew member that he had sent into the shredded rigging to patch the failing sails. Killed early in the battle, his extensive knowledge of the Dutch, as well as his calming hand over the French navy were lost, and what should have been a wondrous victory to the French was at that moment lost. Just before his death, he had expressed his frustration that they could not close with the Dutch, and so his first Lieutenant, Sir Henry Murat, assuming he had desired a rapid engagement, issued the order for the French fleet to charge.

The main mast of the Spartiate falls, killing Marquis Chateaurenault.

Still sailing directly into the Dutch fleet, the French managed to bring their guns around, setting the Burk van Alkmar to flight in multiple deadly salvoes from the large French ships before the brave sloop was also forced to strike its colours. The van Brandenburg and the Wassenaer exchanged several volleys with the much larger Patriote and would eventually strike their colours as well. While both sides had forced a trio of vessels out of the fight, the Dutch had but 2 ships remaining. The Ter Goes and Wapen van Holland, van Almonde’s personal flag ship.

Still sailing directly into the Dutch fleet, the French managed to bring their guns around, setting the Burk van Alkmar to flight in multiple deadly salvoes from the large French ships before the brave sloop was also forced to strike its colours. The van Brandenburg and the Wassenaer exchanged several volleys with the much larger Patriote and would eventually strike their colours as well. While both sides had forced a trio of vessels out of the fight, the Dutch had but 2 ships remaining. The Ter Goes and Wapen van Holland, van Almonde’s personal flag ship.

The Ter Goes and Wapen van Holland surround the Le Malin and Vengeur, which receive crippling fire. The Patriote struggles to close the distance.

Frantically pushing towards the Dutch into the wind, the remaining leaderless and often mast-less vessels of the French navy advanced piecemeal at the rate that their damages sails could individually take them. The last of the Dutch ships were practically at anchor, broadsides turned to the advancing French fleet. The Le Malin managed to arrive relatively intact and was able to exact a great deal of vengeance at point blank to the remaining Dutch ships, though she was outclassed by both her adversaries. Whilst the Le Malin was duelling with the Ter Goes, the Wapen van Holland was actually boarded by the tiny brig, the Vengeur, the sole surviving supporting ship of the French navy. Attempting to distract the mighty flagship, the crew knew they would not win nor survive the assault, but the distraction did prevent the guns from firing over the remaining French ships as they advanced.

Frantically pushing towards the Dutch into the wind, the remaining leaderless and often mast-less vessels of the French navy advanced piecemeal at the rate that their damages sails could individually take them. The last of the Dutch ships were practically at anchor, broadsides turned to the advancing French fleet. The Le Malin managed to arrive relatively intact and was able to exact a great deal of vengeance at point blank to the remaining Dutch ships, though she was outclassed by both her adversaries. Whilst the Le Malin was duelling with the Ter Goes, the Wapen van Holland was actually boarded by the tiny brig, the Vengeur, the sole surviving supporting ship of the French navy. Attempting to distract the mighty flagship, the crew knew they would not win nor survive the assault, but the distraction did prevent the guns from firing over the remaining French ships as they advanced.

The Wapen van Holland rakes the Le Malin, the Spartiate is nowhere in sight.

However, the distraction came to naught. The Patriote and the Spartiate were unable to close the gap before the Le Malin was forced to surrender, nor before the crew of the Vengeur were slaughtered in brutal hand to hand combat by the marines of the Wapen van Holland. Missing great masses of their rigging, and heading directly into the Dutch broadsides, the Patriote and Spartiate were soon captured as well.

However, the distraction came to naught. The Patriote and the Spartiate were unable to close the gap before the Le Malin was forced to surrender, nor before the crew of the Vengeur were slaughtered in brutal hand to hand combat by the marines of the Wapen van Holland. Missing great masses of their rigging, and heading directly into the Dutch broadsides, the Patriote and Spartiate were soon captured as well.

The French ships strike their colours, allowing the Ter Goes to disengage and put themselves in position to receive the remaining French ships.

By the time the fleet had fought its way through the French, the convoy of barges had already disgorged her troops on the French coastline who immediately set about besieging Paris. The battle of Le Havre wouldn’t finish until the fighting had spilled out almost 50 miles west in the Atlantic nearly 12 days later, where the Robuste, the Entrepenante and the Raileur were run down and captured.

By the time the fleet had fought its way through the French, the convoy of barges had already disgorged her troops on the French coastline who immediately set about besieging Paris. The battle of Le Havre wouldn’t finish until the fighting had spilled out almost 50 miles west in the Atlantic nearly 12 days later, where the Robuste, the Entrepenante and the Raileur were run down and captured.

The Dutch fleet still hard at work as the Dutch militia march on Paris.

In fact, the remaining ships were not captured in a direct chase. Though they had to repair much of their rigging to get to speed, the small ships could easily slip away from the larger Dutch ships during the night or by following near thick fog. It was an act of duplicity that saw the last of the French channel fleet captured.

In fact, the remaining ships were not captured in a direct chase. Though they had to repair much of their rigging to get to speed, the small ships could easily slip away from the larger Dutch ships during the night or by following near thick fog. It was an act of duplicity that saw the last of the French channel fleet captured. The Dutch had managed to capture the Spartiate in relatively good order, needing a new mast, but otherwise sea worthy. In nearly a weeks time, the Dutch had replaced the masts and much of her rigging before setting to sea. Staying near the French coast, the Dutch in control of the Spartiate managed to get within visible range of the French ships, who came towards her, thinking it had escaped the battle in French control. However, as the massive 5th rate ship of the line drew closer, the French ensign was thrown aside for the Dutch one, and far in the distance behind it, the Dutch fleet could be seen closing rapidly.

The Dutch had managed to capture the Spartiate in relatively good order, needing a new mast, but otherwise sea worthy. In nearly a weeks time, the Dutch had replaced the masts and much of her rigging before setting to sea. Staying near the French coast, the Dutch in control of the Spartiate managed to get within visible range of the French ships, who came towards her, thinking it had escaped the battle in French control. However, as the massive 5th rate ship of the line drew closer, the French ensign was thrown aside for the Dutch one, and far in the distance behind it, the Dutch fleet could be seen closing rapidly.

The Dutch flag is run up on the Spartiate as the French support brigs are fired upon.

It was a short and brutal battle. The Spartiate alone was sufficient to demoralize and decimate the remaining French sailors and the surviving captains and officers were willing after only a minimal show of effort to surrender their ships to the Dutch in exchange for their lives. Many had not wanted to be killed by their own cannons from their former admiral’s ship.

It was a short and brutal battle. The Spartiate alone was sufficient to demoralize and decimate the remaining French sailors and the surviving captains and officers were willing after only a minimal show of effort to surrender their ships to the Dutch in exchange for their lives. Many had not wanted to be killed by their own cannons from their former admiral’s ship.

The French surrender almost immediately as the Spartiate gets among them.

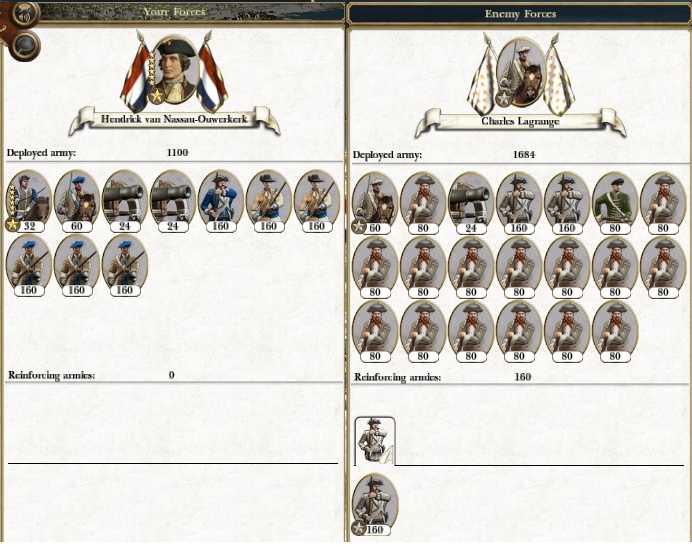

At Paris, things were worse than they were at sea. The city walls slated for construction 2 years prior were on the verge of completion, but could not yet be occupied to prevent the Dutch from invading the city, and so the battle was to take place on an open field. While the Dutch were outnumbered two to three, the French army consisted almost entirely of patriots using barely functional firelock muskets which would not have been out of place over a hundred years ago. Only 700 of the 2000 Frenchmen were part of the regular army, and perhaps a third of their remaining number had been properly drilled in the use of a firearm.

At Paris, things were worse than they were at sea. The city walls slated for construction 2 years prior were on the verge of completion, but could not yet be occupied to prevent the Dutch from invading the city, and so the battle was to take place on an open field. While the Dutch were outnumbered two to three, the French army consisted almost entirely of patriots using barely functional firelock muskets which would not have been out of place over a hundred years ago. Only 700 of the 2000 Frenchmen were part of the regular army, and perhaps a third of their remaining number had been properly drilled in the use of a firearm.

The troop rosters for the Battle of Paris.

The Dutch militia were led by the cousin of William of Orange, Hendrick van Nassau-Ouwerkerk. Having moved back and forth between London and Amsterdam as both General and Master of the Horse in England and in the United Provinces, he was officially commissioned as a general and field marshal of the Dutch but 2 years prior the invasion. Abandoning his London estate house at Downing Street, he set across the channel with but a month to organize the ramshackle militia. Now, his forces were arrayed against a leaderless French garrison at Paris itself.

The Dutch militia were led by the cousin of William of Orange, Hendrick van Nassau-Ouwerkerk. Having moved back and forth between London and Amsterdam as both General and Master of the Horse in England and in the United Provinces, he was officially commissioned as a general and field marshal of the Dutch but 2 years prior the invasion. Abandoning his London estate house at Downing Street, he set across the channel with but a month to organize the ramshackle militia. Now, his forces were arrayed against a leaderless French garrison at Paris itself.

10 Downing Street, the London home of Lord Overkirk.

Not willing to have the main body of French infantry rejoin the garrison and lift the Dutch investment of the city, Ouwerkerk was forced to rapidly march on the city itself. Once taken, he could fortify the city and call in the regulars and conscripts that were rapidly being raised across the united provinces. While unpopular, the conscription bill insured the Dutch army was ready to fight where and when necessary. Most important however, was keeping the militia mostly intact against the French, so that he could easily control the rebellious French countryside.

Not willing to have the main body of French infantry rejoin the garrison and lift the Dutch investment of the city, Ouwerkerk was forced to rapidly march on the city itself. Once taken, he could fortify the city and call in the regulars and conscripts that were rapidly being raised across the united provinces. While unpopular, the conscription bill insured the Dutch army was ready to fight where and when necessary. Most important however, was keeping the militia mostly intact against the French, so that he could easily control the rebellious French countryside.

Ouwerkerk was forced to march in a cold, snowy January to Paris to avoid fighting the main body of French troops.

Ouwerkerk had deployed his aged army in the style of pike and shot. Pike men were put in a central position to support multiple rows of guns, while cannons were positioned to fire between the central lines. He and his cavalry were deployed along the left flank, with the intention of rolling the French back.

Ouwerkerk had deployed his aged army in the style of pike and shot. Pike men were put in a central position to support multiple rows of guns, while cannons were positioned to fire between the central lines. He and his cavalry were deployed along the left flank, with the intention of rolling the French back.

The deployment of the Dutch army.

It was a bloody battle. The French, again with only a junior officer in command, Colonel Charles Legrange, pushed forward in a disorganized mass. Unable to control the patriotic, but ill disciplined citizens, the French right flank of firelock armed citizenry pushed into the Dutch militia, but was almost immediately routed by combined cavalry and pike charges.

It was a bloody battle. The French, again with only a junior officer in command, Colonel Charles Legrange, pushed forward in a disorganized mass. Unable to control the patriotic, but ill disciplined citizens, the French right flank of firelock armed citizenry pushed into the Dutch militia, but was almost immediately routed by combined cavalry and pike charges.

The French advance in a ragged horde, unable to maintain a straight formation.

On the Dutch right, the Dutch pike-men had been moved to fight the French formation, but encountered incredibly stiff resistance and a brutal melee from the professional regiments that had been left to defend Paris. their formation broke on contact, and the brave men fought a bloody melee, sword against gun. Eventually, the bayonet won out, the superior discipline shattering the militia's resolve, but by then it hardly mattered. The plug bayonet having fouled their guns, the remaining regulars were little more than glorified spear men.

On the Dutch right, the Dutch pike-men had been moved to fight the French formation, but encountered incredibly stiff resistance and a brutal melee from the professional regiments that had been left to defend Paris. their formation broke on contact, and the brave men fought a bloody melee, sword against gun. Eventually, the bayonet won out, the superior discipline shattering the militia's resolve, but by then it hardly mattered. The plug bayonet having fouled their guns, the remaining regulars were little more than glorified spear men.

A general melee on the left broke out, while the pike men on the right engage the French line infantry.

Even though the Dutch had routed the French right flank, the Dutch left wing of pike men and cavalry had nearly run dry. Unable to decisively rout the French center after turning the flank, a bloody melee broke out between the militia and the French citizenry. While both regiments of pike militia were routed, they had taken hundreds of French citizens along with them. The Gendarmarie of the Dutch had also routed, leaving the Dutch with their small regular force, the musket armed militia, the cannons, general Ouwerkerk and his general staff. The French still had hundreds of troops, including two detachments of their professional army.

Even though the Dutch had routed the French right flank, the Dutch left wing of pike men and cavalry had nearly run dry. Unable to decisively rout the French center after turning the flank, a bloody melee broke out between the militia and the French citizenry. While both regiments of pike militia were routed, they had taken hundreds of French citizens along with them. The Gendarmarie of the Dutch had also routed, leaving the Dutch with their small regular force, the musket armed militia, the cannons, general Ouwerkerk and his general staff. The French still had hundreds of troops, including two detachments of their professional army.

The Dutch rearranging their lines of militia to fire on the French lines.

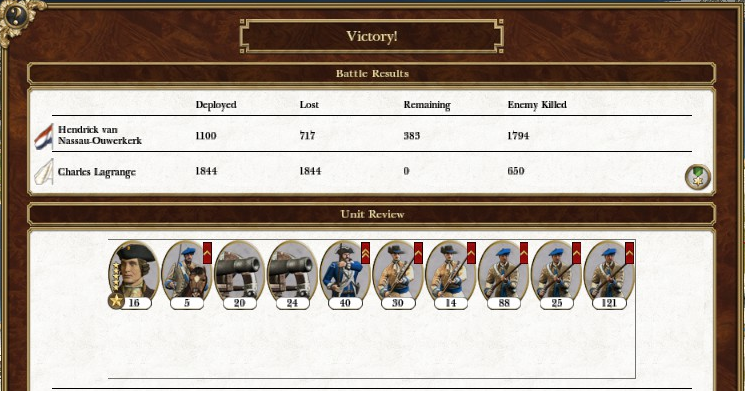

After half an hour of fighting through the center of the French and Dutch lines the French finally collapsed under the much greater weight of Dutch bullets, which outnumbered their own guns greatly. Only the Paris guard, and the colonel’s personal guard remained arrayed against the remaining three hundred Dutch militia and their cannons. Forced to advance into the teeth of the Dutch guns, the French, who were already on the brink of collapse, lost all hope as Colonel Legrange was decapitated by a cannonball. The Dutch formed a rapid charge, which ousted the final piece of French resistance in the Parisian garrison.

After half an hour of fighting through the center of the French and Dutch lines the French finally collapsed under the much greater weight of Dutch bullets, which outnumbered their own guns greatly. Only the Paris guard, and the colonel’s personal guard remained arrayed against the remaining three hundred Dutch militia and their cannons. Forced to advance into the teeth of the Dutch guns, the French, who were already on the brink of collapse, lost all hope as Colonel Legrange was decapitated by a cannonball. The Dutch formed a rapid charge, which ousted the final piece of French resistance in the Parisian garrison.

The final French infantry charge against the Dutch, outnumbered at that time three to one.

The daring assault starting at sea and ending in the streets of Paris was a success. One that few would have dreamed possible. However, the situation was not ideal for the Dutch. Their army had lost over 700 men, leaving a very depleted garrison to hold Paris. The countryside was lit with patriotic fervor, and the main French army which had turned to Westphalia turned its eyes back west to Paris. Ouwerkerk spent no small amount of time immediately drafting the local radicals and republicans into his militia force. Already in a shambles, he was desperate to enlist whoever he could, and his dispatches to Amsterdam called for a thousand able bodied troops, which could not be found. France had been taken. Time would tell if it could be held.

The daring assault starting at sea and ending in the streets of Paris was a success. One that few would have dreamed possible. However, the situation was not ideal for the Dutch. Their army had lost over 700 men, leaving a very depleted garrison to hold Paris. The countryside was lit with patriotic fervor, and the main French army which had turned to Westphalia turned its eyes back west to Paris. Ouwerkerk spent no small amount of time immediately drafting the local radicals and republicans into his militia force. Already in a shambles, he was desperate to enlist whoever he could, and his dispatches to Amsterdam called for a thousand able bodied troops, which could not be found. France had been taken. Time would tell if it could be held.

The survivors of the Battle of Paris number fewer than 400 Dutch soldiers. The remaining few French soldiers throw down their arms and coats and meld with the citizens.

Cayenne and Martinique were also taken immediately by the much better equipped Dutch American trade armies. Martinique was taken by the professional force of colonial marines from the Leeward Islands with no resistance, while native auxiliaries and militia captured Cayenne after a short but brutal battle against a primarily native garrison. Of note, the Dutch native auxiliaries, armed only with their traditional hand crafted axes performed with particular valour, destroying and disrupting several companies of native bowmen.

Cayenne and Martinique were also taken immediately by the much better equipped Dutch American trade armies. Martinique was taken by the professional force of colonial marines from the Leeward Islands with no resistance, while native auxiliaries and militia captured Cayenne after a short but brutal battle against a primarily native garrison. Of note, the Dutch native auxiliaries, armed only with their traditional hand crafted axes performed with particular valour, destroying and disrupting several companies of native bowmen.

Native auxiliary infantry wearing dapper blue Dutch coats were a brave and effective shock force in the 1700s.

News of the assault and capture of Paris set Europe ablaze. The Spanish, which had not taken the threat of the Dutch seriously, declared war by the following June, but were preempted by the Dutch at Flanders, where the new formed Dutch regulars under Christiaan van Waldeck had waited to pounce. The sparse garrison traditionally under the aegis of their French allies where quickly overrun.

News of the assault and capture of Paris set Europe ablaze. The Spanish, which had not taken the threat of the Dutch seriously, declared war by the following June, but were preempted by the Dutch at Flanders, where the new formed Dutch regulars under Christiaan van Waldeck had waited to pounce. The sparse garrison traditionally under the aegis of their French allies where quickly overrun.

The tiny Flander's garrison is quickly surrounded and overrun.

The French stationed around Alsace Loraine were forced into indecision when Claude de Vilars was murdered at an estate in the town of Nancy, leaving Camille d’ Hostun in charge. He was not made aware of his promotion to Field Marshall as Vilars wasn't found dead for nearly a week after his death. It had appeared that he had been lynched by royalists who personally blamed Vilars for the fall of Paris. It could have been coincidence, but Ganesvoort, the Dutch spymaster and agent provocateur was in Nancy at the time, hiding well away from Paris or any nobility that could identify him. Without their premier general, their armies in disarray, Paris and the countryside taken, France had been virtually destroyed.

The French stationed around Alsace Loraine were forced into indecision when Claude de Vilars was murdered at an estate in the town of Nancy, leaving Camille d’ Hostun in charge. He was not made aware of his promotion to Field Marshall as Vilars wasn't found dead for nearly a week after his death. It had appeared that he had been lynched by royalists who personally blamed Vilars for the fall of Paris. It could have been coincidence, but Ganesvoort, the Dutch spymaster and agent provocateur was in Nancy at the time, hiding well away from Paris or any nobility that could identify him. Without their premier general, their armies in disarray, Paris and the countryside taken, France had been virtually destroyed.This has been the second look into the second 80 years war, presented by David Stephenson. Next, the London symphony orchestra will be performing Beethoven’s 5th symphony. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.