Part 12: December 5 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be playing several pieces by Pyotre Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and following that, we will be presenting an analysis of the nutcracker waltz. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twelfth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the Dutch strategy as they attempted to attack Britain.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twelfth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the Dutch strategy as they attempted to attack Britain. By now, the Dutch battalions were often down to half strength or less. Virtually no battalions remained at full strength, meaning their army numbers were deceptive. It would take 3 years and 30 million guilders to repair them, crippling the ability of the Dutch government to raise new battalions. Despite that, between 1722 and 1744, 15 new battalions were raised, or over 2000 men.

By now, the Dutch battalions were often down to half strength or less. Virtually no battalions remained at full strength, meaning their army numbers were deceptive. It would take 3 years and 30 million guilders to repair them, crippling the ability of the Dutch government to raise new battalions. Despite that, between 1722 and 1744, 15 new battalions were raised, or over 2000 men.

While the battalion list implied a large army, the Dutch battalions were down to as few as 9 men.

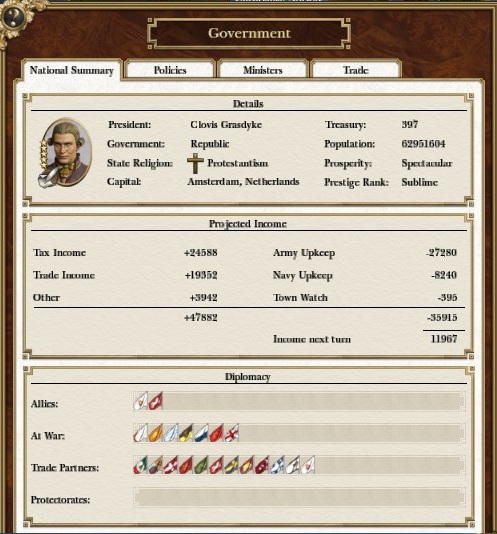

And administrating them was a new cabinet. For the first time in decades, the Orange party could not win the election, their popularity at an all time low after their mistakes during their time in office. The republican party was skilled, diplomatic and far less militant. The aged Clovis Grasdyke had taken the reigns as Statholder, and had assessed the Dutch situation as untenable in terms of offense. He would spend his first term consolidating Dutch holdings, and preparing for a major offensive years down the line.

And administrating them was a new cabinet. For the first time in decades, the Orange party could not win the election, their popularity at an all time low after their mistakes during their time in office. The republican party was skilled, diplomatic and far less militant. The aged Clovis Grasdyke had taken the reigns as Statholder, and had assessed the Dutch situation as untenable in terms of offense. He would spend his first term consolidating Dutch holdings, and preparing for a major offensive years down the line.

Elected in 1722, the Republican party finally won an election. Campaigning on their reputation as older, more experienced politicians, the young and energetic ministers were perhaps too impatient in their policies and conquests.

Those thousands of soldiers pushed to the front were a tremendous tax burden. The total army cost rose from 52 million guilders every year, to 76 million guilders every year. The new battalions they rose cost them an initial cost of almost a year’s profits. Unlike nearly every year prior, the Dutch could not raise new factories, or expand industry or commerce in any theater, and profits dropped like a rock.

Those thousands of soldiers pushed to the front were a tremendous tax burden. The total army cost rose from 52 million guilders every year, to 76 million guilders every year. The new battalions they rose cost them an initial cost of almost a year’s profits. Unlike nearly every year prior, the Dutch could not raise new factories, or expand industry or commerce in any theater, and profits dropped like a rock.

Dutch finances in 1722, at the start of Clovis' term. Military costs were already exorbitant, but expansion and reinforcement would increase the bi-annual cost to 150% this value.

Even worse were constant raids across several Dutch theaters. The Cherokee in the Americas, the Bavarians in Germany and the Marathas in India, all incapable of directly challenging the Dutch in combat constantly raided the Dutch countryside, burning down factories, fields and schools. The total in tax and trade revenue after considering losses was down from 20 million guilders every year to 10. These expenditures were considered necessary, and the republican government couldn’t simply ignore that the Dutch needed to be prepared for war and conquest.

Even worse were constant raids across several Dutch theaters. The Cherokee in the Americas, the Bavarians in Germany and the Marathas in India, all incapable of directly challenging the Dutch in combat constantly raided the Dutch countryside, burning down factories, fields and schools. The total in tax and trade revenue after considering losses was down from 20 million guilders every year to 10. These expenditures were considered necessary, and the republican government couldn’t simply ignore that the Dutch needed to be prepared for war and conquest.

The Dutch weren't hastled by major engagements. Instead, raiders focused on damaging the Dutch economy. Anything to slow the Dutch Juggernaut.

The early 1720s were relatively peaceful, with the Dutch battalions too crippled to continue fighting, and their opponents without the armies needed to beat them. After accounting for reinforcements of their damaged battalions, the Dutch had several options available to them when considering their new army regiments and where they would be.

The early 1720s were relatively peaceful, with the Dutch battalions too crippled to continue fighting, and their opponents without the armies needed to beat them. After accounting for reinforcements of their damaged battalions, the Dutch had several options available to them when considering their new army regiments and where they would be. In India, the Dutch had only average line infantry, but very weak cavalry. V.O.C. company cavalry were comparable to the Gendarme of Europe. They were weaker than provincial cavalry, and were certainly no match for the Indian lancers and camel nomads. That difference in cavalry meant in the Indian theater, the Dutch had to focus on their line infantry, using only a little cavalry to destroy artillery.

In India, the Dutch had only average line infantry, but very weak cavalry. V.O.C. company cavalry were comparable to the Gendarme of Europe. They were weaker than provincial cavalry, and were certainly no match for the Indian lancers and camel nomads. That difference in cavalry meant in the Indian theater, the Dutch had to focus on their line infantry, using only a little cavalry to destroy artillery.

Dutch V.O.C. cavalry were far inferior to the cavalry of India. Unable to block enemy cavalry or seek out and destroy the Sidar lancers, they were relegated only to flanking infantry and spiking artillery.

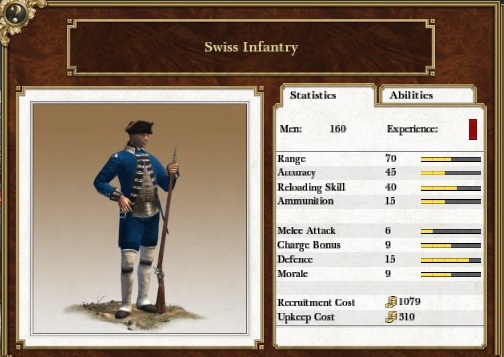

In the European theater, the Dutch had far more options. The Swiss were the best shots they could hire, but at a considerable premium. The Scots could also be hired, and were considered the best close quarters fighters in Europe, better even than the Barghir in India. However, they were no better shots than the standard line infantry, and cost a premium.

In the European theater, the Dutch had far more options. The Swiss were the best shots they could hire, but at a considerable premium. The Scots could also be hired, and were considered the best close quarters fighters in Europe, better even than the Barghir in India. However, they were no better shots than the standard line infantry, and cost a premium.

The Dutch planned on purchasing more of the excellent Swiss mercenaries. While costly, their reputation preceded them, and their accuracy with the musket was unmatched across Europe.

Grenadiers were recruited in small numbers to supplement a few Dutch armies. Their undersized battalions could use their deadly grenades to quickly shatter small sections of the enemy line, giving the Dutch a chance to encircle their enemy’s forces. The grenade was a short fused iron pot filled with black powder. The men who used these were the tallest, strongest and best trained men they could find in the United Provinces, as it took strong men to throw the heavy iron bombs. Because of their stature and strength, they were considerably stronger than average in melee combat.

Grenadiers were recruited in small numbers to supplement a few Dutch armies. Their undersized battalions could use their deadly grenades to quickly shatter small sections of the enemy line, giving the Dutch a chance to encircle their enemy’s forces. The grenade was a short fused iron pot filled with black powder. The men who used these were the tallest, strongest and best trained men they could find in the United Provinces, as it took strong men to throw the heavy iron bombs. Because of their stature and strength, they were considerably stronger than average in melee combat.

Grenadiers, already tall, could be easily identified by their tall caps. The Dutch recruited several to attach to their armies, as their grenades could very potently destroy small breaches in enemy lines.

For cavalry, the Dutch could recruit a much wider variety of cavalry. Both light and heavy dragoons offered a versatile formation, but could not shatter infantry in a strong rear charge. They could rely on their medium provincial cavalry, effective when charging but slow moving. They were a solid choice to intercept and defeat enemy cavalry. The one the Dutch settled on recruiting were the light Hussar regiments. Hussars were light cavalry, and in some ways the opposite of grenadiers. Only the shortest, lightest men could be made Hussars, as it let their horses run much faster. The Hussars were originally an Eastern Europe formation, but their success made them popular even as far as Amsterdam. They were ideal to run down fleeing enemies and spike enemy artillery. The Dutch, opting away from direct cavalry charges would use the less versatile, but agile Hussars to provide mobility in their armies. That they were inexpensive was an added benefit for the rapidly constricting Dutch purse.

For cavalry, the Dutch could recruit a much wider variety of cavalry. Both light and heavy dragoons offered a versatile formation, but could not shatter infantry in a strong rear charge. They could rely on their medium provincial cavalry, effective when charging but slow moving. They were a solid choice to intercept and defeat enemy cavalry. The one the Dutch settled on recruiting were the light Hussar regiments. Hussars were light cavalry, and in some ways the opposite of grenadiers. Only the shortest, lightest men could be made Hussars, as it let their horses run much faster. The Hussars were originally an Eastern Europe formation, but their success made them popular even as far as Amsterdam. They were ideal to run down fleeing enemies and spike enemy artillery. The Dutch, opting away from direct cavalry charges would use the less versatile, but agile Hussars to provide mobility in their armies. That they were inexpensive was an added benefit for the rapidly constricting Dutch purse.

At the time, the Dutch cavalry options at home were relatively limited, but so were the other cavalry of Europe. The Dutch Hussars were sufficient to counter provincial cavalry, but moved considerably faster.

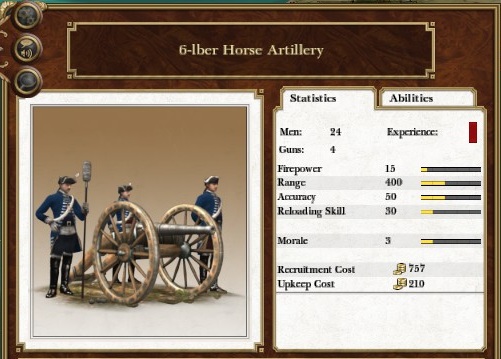

When looking at artillery, the Dutch favoured the light 6 pound horse artillery and the 24 pound howitzer. The 6 pound guns were ideal against armies in the field, while the Howitzer was useful in rough or obstructed terrain, even around enemy fortifications. The 12 pound foot artillery wasn’t necessary in combat against infantry, and against fortifications, they preferred the howitzers, even though fortification defenses could often outrange them.

When looking at artillery, the Dutch favoured the light 6 pound horse artillery and the 24 pound howitzer. The 6 pound guns were ideal against armies in the field, while the Howitzer was useful in rough or obstructed terrain, even around enemy fortifications. The 12 pound foot artillery wasn’t necessary in combat against infantry, and against fortifications, they preferred the howitzers, even though fortification defenses could often outrange them.

The 6 pound horse cannon was light enough that a team of horses could move it very rapidly. Faster than infantry could run. However, their light munitions were insufficient to defeat fortress walls, forcing them into a specialist role in firing only at enemy armies.

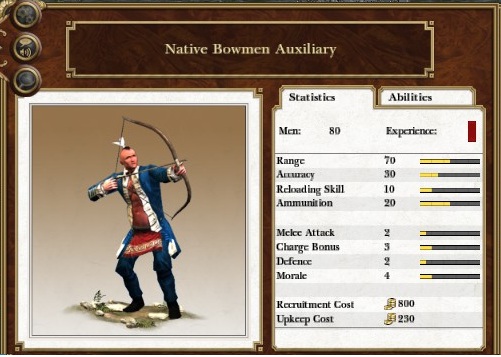

In the Americas, the Dutch had to make due with the men they could find locally. Natives could be armed much like the men in India, in the European style, but they did not take well to it. They vastly preferred an irregular style of fighting, either fighting with their muskets in a loose, disorganized formation, or using bows to pick enemies off at a distance. Giving up on the idea of using the natives as a disciplined firing line, the Dutch instead had them use their traditional hand axes to act as a sort of shock troop. For their firing line, the Dutch simply used colonial marines, which were essentially boat transported line infantry. These line infantry were identical to the line infantry in Europe, but unlike the V.O.C., they were not matched against overwhelming discipline and fire power. Instead, the local natives fought in near disorganized mobs relying on stealth, terrain and ambush to fight.

In the Americas, the Dutch had to make due with the men they could find locally. Natives could be armed much like the men in India, in the European style, but they did not take well to it. They vastly preferred an irregular style of fighting, either fighting with their muskets in a loose, disorganized formation, or using bows to pick enemies off at a distance. Giving up on the idea of using the natives as a disciplined firing line, the Dutch instead had them use their traditional hand axes to act as a sort of shock troop. For their firing line, the Dutch simply used colonial marines, which were essentially boat transported line infantry. These line infantry were identical to the line infantry in Europe, but unlike the V.O.C., they were not matched against overwhelming discipline and fire power. Instead, the local natives fought in near disorganized mobs relying on stealth, terrain and ambush to fight.

Armed with bows or European muskets, native infantry fighting at range were incompatible with the drilled discipline of a firing line. The Dutch made them shock specialists in melee rather than funding bows or irregular musket fire.

All these considerations would take years to solidify. As it were, the Dutch economy was rapidly spiralling downward due to rampant military spending, and without the means to improve their infrastructure, creating new armies would be far down the road. At this point, the only silver lining was that their titanic economy was still exceeding their spending. The armies had already become massive in size, with a total of 23,000 Dutch under arms. An incredible sum considering that near 10,000 had been killed in the disaster that was 1720 to 1721.

All these considerations would take years to solidify. As it were, the Dutch economy was rapidly spiralling downward due to rampant military spending, and without the means to improve their infrastructure, creating new armies would be far down the road. At this point, the only silver lining was that their titanic economy was still exceeding their spending. The armies had already become massive in size, with a total of 23,000 Dutch under arms. An incredible sum considering that near 10,000 had been killed in the disaster that was 1720 to 1721.

Dutch military upkeep had increased dramatically, but after Meijer was sacked and replaced by the hyper competent Karel van der Werff, upkeep actually paid was increased only a few million guilders every year.

By 1724, the enemies of the United Provinces had amassed a few small armies which were able to burn down and attack small economic centers of the Dutch Empire. These armies forced the Dutch into action, and in late 1724 the Dutch offensive continued. With a massive deficit in infantry and numbers, the Bavarian army sent to harass the Dutch in Westphalia was quickly destroyed as the same army moved south to Munich. They were supposed to link up with Waaldeck from Milan, but the old general had contracted typhoid after an evidently unsanitary eye surgery and died in 1723. Ouwerkerk and his old ways would be in charge until they Dutch could afford a replacement general to lead their new model army.

By 1724, the enemies of the United Provinces had amassed a few small armies which were able to burn down and attack small economic centers of the Dutch Empire. These armies forced the Dutch into action, and in late 1724 the Dutch offensive continued. With a massive deficit in infantry and numbers, the Bavarian army sent to harass the Dutch in Westphalia was quickly destroyed as the same army moved south to Munich. They were supposed to link up with Waaldeck from Milan, but the old general had contracted typhoid after an evidently unsanitary eye surgery and died in 1723. Ouwerkerk and his old ways would be in charge until they Dutch could afford a replacement general to lead their new model army.

Christiaan van Waldeck was brought back to Amsterdam and given a heroes funeral for his conquest of Spain.

The Dutch deployment saw the garrison of Gibraltar move to Morocco, besieging the city and hoping to starve it out. The Arcot army near the eastern coast of India moved to take Hyderabad. Defended by only a few raiding parties that scattered at the approach, Hyderabad capitulated without a fight to the early Dutch push, but the Dutch were incapable of making it a profitable venture, as the buildings had been torched and their fields plundered. The city was in such a state of mutiny that their taxes had to be cut, and the city ended up more a drain on their resources than it was a benefit with thousands of guilders being put to their policing. The army brought back into reserve at Mysore was pushed forward towards Bangalore, while the still depleted Goa army was used to destroy irregular formations attempting to cause havoc in the interior of the Dutch held India. Across the whole advance North, the Dutch encountered tiny raiding groups, dispatching them as they drove towards their cities forcing the Indian soldiers to regroup around Arcot, hoping to slip past the army in Hyderabad and take their back city. Lastly, in the Americas, the Dutch moved troops from Jamaica and Port Royal to try to take out the sizeable garrison in Nassau.

The Dutch deployment saw the garrison of Gibraltar move to Morocco, besieging the city and hoping to starve it out. The Arcot army near the eastern coast of India moved to take Hyderabad. Defended by only a few raiding parties that scattered at the approach, Hyderabad capitulated without a fight to the early Dutch push, but the Dutch were incapable of making it a profitable venture, as the buildings had been torched and their fields plundered. The city was in such a state of mutiny that their taxes had to be cut, and the city ended up more a drain on their resources than it was a benefit with thousands of guilders being put to their policing. The army brought back into reserve at Mysore was pushed forward towards Bangalore, while the still depleted Goa army was used to destroy irregular formations attempting to cause havoc in the interior of the Dutch held India. Across the whole advance North, the Dutch encountered tiny raiding groups, dispatching them as they drove towards their cities forcing the Indian soldiers to regroup around Arcot, hoping to slip past the army in Hyderabad and take their back city. Lastly, in the Americas, the Dutch moved troops from Jamaica and Port Royal to try to take out the sizeable garrison in Nassau.

The Dutch position in Hyderabad was unprofitable, untenable, and their buildings were commonly burned down by Maratha raiders. However, denying it to the Marathas was a necessary blow.

They weren’t the only ones on the move however. The massive British channel fleet had gone missing, and the Dutch couldn't find them anywhere near them. With their armies so thoroughly out of position, the Dutch were incapable of capitalizing on this absence and could not cross her forces across the channel, which would have ended the war very quickly indeed.

They weren’t the only ones on the move however. The massive British channel fleet had gone missing, and the Dutch couldn't find them anywhere near them. With their armies so thoroughly out of position, the Dutch were incapable of capitalizing on this absence and could not cross her forces across the channel, which would have ended the war very quickly indeed.

The British navy and army had moved from the channel, much to the alarm of the Dutch. The United Provinces, so far out of position, were completely incapable of capitalizing.

The British fleet in fact, was seen with a full flotilla of transport ships around the East Indies according to several Dutch trade ships that had retreated from them. The Dutch had figured that the British were preparing to invade Dutch positions held in India, but had wanted to destroy any Dutch fleets that could have stranded their troops on India beforehand. It was also possible that they had intended to land around Panama and attack eastward to Dutch holdings in the northern coast of South America. The Dutch had to prepare for either event.

The British fleet in fact, was seen with a full flotilla of transport ships around the East Indies according to several Dutch trade ships that had retreated from them. The Dutch had figured that the British were preparing to invade Dutch positions held in India, but had wanted to destroy any Dutch fleets that could have stranded their troops on India beforehand. It was also possible that they had intended to land around Panama and attack eastward to Dutch holdings in the northern coast of South America. The Dutch had to prepare for either event.

The V.O.C. trade fleet encounters the British channel fleet before retreating half way round the globe to Madagascar.

Also, the British were moving in the Mediterranean. Having captured Tunisia from the Prussians, the British clearly intended to expand their resource base on North Africa to contend the Dutch control of Spain. Dutch frigates and support ships were tentatively prepared to intercept or evade the British ships of the line. While the Dutch had considerably more numbers, the British were using a heavier class of ship. The Dutch would likely have to rely on bomb ketches to ignite the British rigging preventing her from returning fire without risking an explosion. They could also hope to hold the British Mediterranean fleet back until their channel fleet had ferried their troops across the channel, freeing them up to move south and overwhelm the British fleet.

Also, the British were moving in the Mediterranean. Having captured Tunisia from the Prussians, the British clearly intended to expand their resource base on North Africa to contend the Dutch control of Spain. Dutch frigates and support ships were tentatively prepared to intercept or evade the British ships of the line. While the Dutch had considerably more numbers, the British were using a heavier class of ship. The Dutch would likely have to rely on bomb ketches to ignite the British rigging preventing her from returning fire without risking an explosion. They could also hope to hold the British Mediterranean fleet back until their channel fleet had ferried their troops across the channel, freeing them up to move south and overwhelm the British fleet.

The British in Algiers had established a strong fleet of ships of the line. The Dutch countered with an explosive bomb firing support ship to bolster their frigates, the Spartiate and the Ter Goes.

With the Dutch besieging Morocco, if they managed to take it, the North African theater would provide yet another avenue of attack for the Dutch and British forces across the world, which would make it the widest spread war the world would see for over 2 centuries, and it was already the widest spread war to have ever occurred.

With the Dutch besieging Morocco, if they managed to take it, the North African theater would provide yet another avenue of attack for the Dutch and British forces across the world, which would make it the widest spread war the world would see for over 2 centuries, and it was already the widest spread war to have ever occurred. By late 1724 hostilities had recommenced in earnest with the major battle of Morocco. The Dutch forces from Gibraltar besieging the city had forced the isolated Moroccans out of their fortress into an open field battle. Outnumbered, the Dutch simply deployed in as long and thin a line as they possibly could. Under normal circumstances, this would have been a tremendous advantage over their opponents, but in this battle, the Dutch were had mostly militia, which were to be used in dense formations only.

By late 1724 hostilities had recommenced in earnest with the major battle of Morocco. The Dutch forces from Gibraltar besieging the city had forced the isolated Moroccans out of their fortress into an open field battle. Outnumbered, the Dutch simply deployed in as long and thin a line as they possibly could. Under normal circumstances, this would have been a tremendous advantage over their opponents, but in this battle, the Dutch were had mostly militia, which were to be used in dense formations only.

The Dutch militia spread thin to counter the large North African army.

As bloody a battle as their thin lines made it, the Dutch did manage a victory. As they had the only cannons in the field, they were easily able to draw the Moroccans into their gun fire. Relying on Amazon warrior women and dessert nomads, none of whom were well versed in anti cavalry doctrine, the 4 battalions of medium cavalry held in reserve by the Dutch managed to break the backs of many of the Moroccan units as they engaged the line infantry and militia from the front. The camel gunner cavalry used by the Moroccans were both too slow and too inept in melee to try to emulate this tactic, and were incapable of catching the Dutch provincial horse. By the end of the day however, the Morrocan army maintained a hold of their fortress leaving the Dutch to remain outside their walls until 1725.

As bloody a battle as their thin lines made it, the Dutch did manage a victory. As they had the only cannons in the field, they were easily able to draw the Moroccans into their gun fire. Relying on Amazon warrior women and dessert nomads, none of whom were well versed in anti cavalry doctrine, the 4 battalions of medium cavalry held in reserve by the Dutch managed to break the backs of many of the Moroccan units as they engaged the line infantry and militia from the front. The camel gunner cavalry used by the Moroccans were both too slow and too inept in melee to try to emulate this tactic, and were incapable of catching the Dutch provincial horse. By the end of the day however, the Morrocan army maintained a hold of their fortress leaving the Dutch to remain outside their walls until 1725.

The Dutch dead number in the hundreds, making it a very costly victory, especially considering Morocco remained in Moroccan hands.

In early 1725, the Dutch troops in Bavaria faced a similar situation. However, the Dutch were outnumbered at the siege of Munich too heavily, and so they retreated back so they could link back up with the Amsterdam Guard army which had just beaten the forward element of the Bavarian army. Now clear of the vandals that threatened the industry of Europe, the Dutch were in a good position to push further east. Each push however, took them further away from a now critically exposed England.

In early 1725, the Dutch troops in Bavaria faced a similar situation. However, the Dutch were outnumbered at the siege of Munich too heavily, and so they retreated back so they could link back up with the Amsterdam Guard army which had just beaten the forward element of the Bavarian army. Now clear of the vandals that threatened the industry of Europe, the Dutch were in a good position to push further east. Each push however, took them further away from a now critically exposed England.

The Dutch offensive recommenced, pushing further east. Replenishing armies took all the funds that could have otherwise funded an army to take Britain.

Even in India, the Dutch were faced with armies sallying forth from their cities to lift Dutch sieges. Around Bangalore, the Indian army faced a Dutch force consisting almost entirely of V.O.C. line infantry. Those line infantry simply fired their volleys into the Maratha army and pushed them back without too much difficulty. V.O.C. cavalry managed to rout a few battalions who were entangled in melee combat against the V.O.C., and the backup was greatly appreciated by the infantry who were superior in a gun fight, but inferior where charged.

Even in India, the Dutch were faced with armies sallying forth from their cities to lift Dutch sieges. Around Bangalore, the Indian army faced a Dutch force consisting almost entirely of V.O.C. line infantry. Those line infantry simply fired their volleys into the Maratha army and pushed them back without too much difficulty. V.O.C. cavalry managed to rout a few battalions who were entangled in melee combat against the V.O.C., and the backup was greatly appreciated by the infantry who were superior in a gun fight, but inferior where charged.

V.O.C. infantry line up from horizon to horizon in India. Unable to rely on their cavalry, and with their superior gun drill compared to the Sepoy's, Dutch V.O.C. armies had become very one dimensional.

It was a fairly simple and straightforward battle. Dutch line infantry were in a strong position to destroy weak elements in the Maratha lines, and the cavalry used those gaps to encircle their stronger battalions. The more uniform Dutch lines on the other hand, had no open gaps available for the Maratha cavalry, who were repelled in a bloody series of frontal charges.

It was a fairly simple and straightforward battle. Dutch line infantry were in a strong position to destroy weak elements in the Maratha lines, and the cavalry used those gaps to encircle their stronger battalions. The more uniform Dutch lines on the other hand, had no open gaps available for the Maratha cavalry, who were repelled in a bloody series of frontal charges.

The Dutch line is charged all across the front. The Maratha charge has gaps which are exploited in counter charges and cavalry maneuvers.

Once again, after 2 years consolidating their position, the Dutch were making advances across India and Europe. For now, the Americas could wait until the Dutch army at Nassau could destroy the British threatening the Dutch flanks while their other armies advanced.

Once again, after 2 years consolidating their position, the Dutch were making advances across India and Europe. For now, the Americas could wait until the Dutch army at Nassau could destroy the British threatening the Dutch flanks while their other armies advanced.

A Dutch marine army moves to take the Bahamas. Once it is taken, it will land in Florida allowing the Dutch an advance northward.

Even so, these advances were becoming more and more costly, and provinces taken were not able to repay the costs let alone the tragic human costs. With tax and trade fees from newly acquired provinces barely covering the expense of policing them, the Dutch would have to shatter the Maratha and Austrian will to fight if they desired keeping any of their profits from their new territories.

Even so, these advances were becoming more and more costly, and provinces taken were not able to repay the costs let alone the tragic human costs. With tax and trade fees from newly acquired provinces barely covering the expense of policing them, the Dutch would have to shatter the Maratha and Austrian will to fight if they desired keeping any of their profits from their new territories.

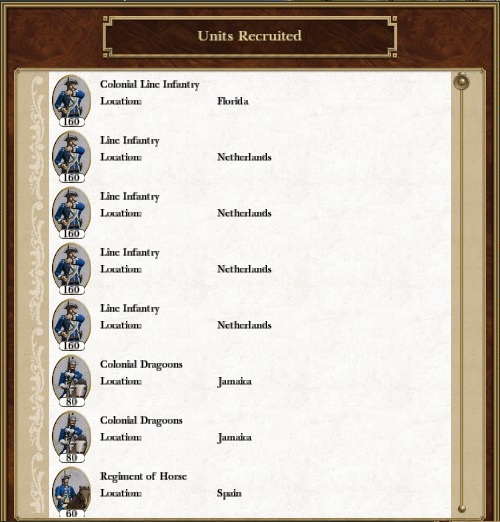

Maintaining the war was costly in both men and money. The Dutch recruitment just before 1725 involved thousands of men.

In our next broadcast, we will be looking into the broadening war, and the unstoppable Dutch. Next we will be listening to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. In half an hour, we will be presenting an analysis of the nutcracker waltz. World news has been moved back an hour for today and for the rest of the Christmas season. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

In our next broadcast, we will be looking into the broadening war, and the unstoppable Dutch. Next we will be listening to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. In half an hour, we will be presenting an analysis of the nutcracker waltz. World news has been moved back an hour for today and for the rest of the Christmas season. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.