Part 18: December 23 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be discussing an atheist's Christmas. How to enjoy the holidays, without worshiping Christ. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the eighteenth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the Dutch invasion of Austria, their situation in the Americas and their election.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the eighteenth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the Dutch invasion of Austria, their situation in the Americas and their election. Taking a moment to look away from the Dutch as they spread across the world, far to the East, their influence over a small island nation would create one of the most advanced armies in the conflicts of the 1970s. The small insular nation of Japan, which had banned all European trade after the Sengoku war, had allowed the trade nation of the United Provinces to exchange knowledge and technology from the small southern port city of Dejima in Nagasaki harbour. Even then, the Dutch could not sell the Japanese any books until 1720, limiting the Japanese ability to learn of the world at large save through word of mouth.

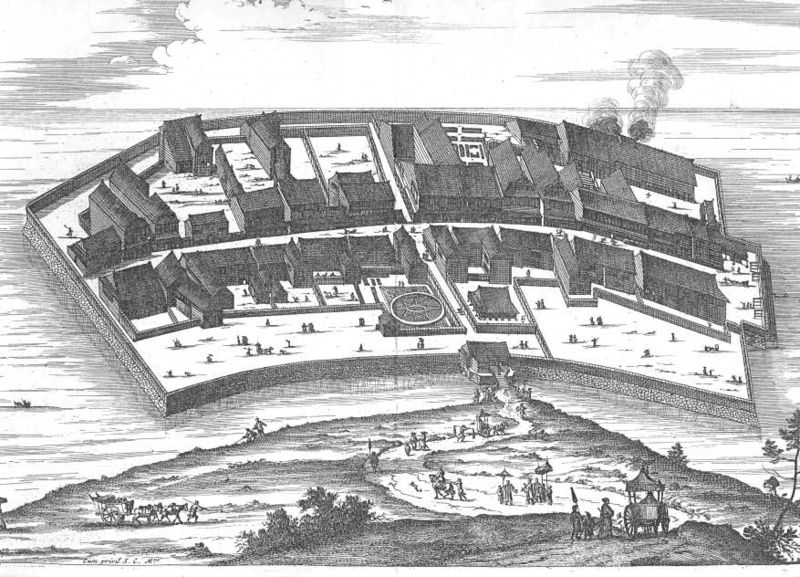

Taking a moment to look away from the Dutch as they spread across the world, far to the East, their influence over a small island nation would create one of the most advanced armies in the conflicts of the 1970s. The small insular nation of Japan, which had banned all European trade after the Sengoku war, had allowed the trade nation of the United Provinces to exchange knowledge and technology from the small southern port city of Dejima in Nagasaki harbour. Even then, the Dutch could not sell the Japanese any books until 1720, limiting the Japanese ability to learn of the world at large save through word of mouth.

Dejima was created for trade with foreigners. It was completely shut off from the rest of Japan preventing the spread of Western influence from leaving the small port.

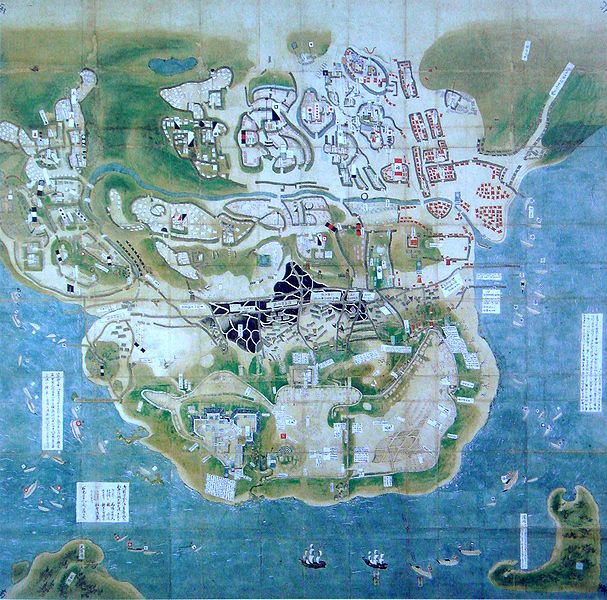

Shortly after the time the Dutch could trade and sell books, knowledge of European advancements, politics and philosophy, printed from machine print factories by the V.O.C. was cheap enough that their knowledge had spread over much of Japan. What most intrigued the Japanese were the maps that the Dutch had made updated from the start of the mid 1500s to the then present day. What had interested the Japanese was that a nation that had scarcely existed until 1581 had come to conquer an expanse of land greater than that of China, ruling over more people and earning more money. Their Empire stretched from a continent that the Japanese had never had any contact with, all the way to the east in India.

Shortly after the time the Dutch could trade and sell books, knowledge of European advancements, politics and philosophy, printed from machine print factories by the V.O.C. was cheap enough that their knowledge had spread over much of Japan. What most intrigued the Japanese were the maps that the Dutch had made updated from the start of the mid 1500s to the then present day. What had interested the Japanese was that a nation that had scarcely existed until 1581 had come to conquer an expanse of land greater than that of China, ruling over more people and earning more money. Their Empire stretched from a continent that the Japanese had never had any contact with, all the way to the east in India.

Maps printed in the 1700s were less accurate than those today, but the scale of Dutch conquest across those maps still intrigued the Japanese.

The local lords, many of whom were opposed to the Shogun after the Sengoku war, the largest civil war Japan had seen up until that time were of course, greatly interested in the progress the Dutch had made. Lords and scholars traveled to Dejima by the dozens for “Rangaku” meaning “Dutch studies.” These scholars were heavily influenced by Dutch industrial and scientific thinking. The Shimazu were particularly influenced by the Rangaku Dutch studies, and they were given the Shogun’s blessing to send a small number of scholars and generals aboard V.O.C. ships to see the extent of the Dutch Empire, and their advanced factories. Primarily, wishing to assess and spy on the western powers, the Dutch were more than happy to flaunt their wealth and prestige.

The local lords, many of whom were opposed to the Shogun after the Sengoku war, the largest civil war Japan had seen up until that time were of course, greatly interested in the progress the Dutch had made. Lords and scholars traveled to Dejima by the dozens for “Rangaku” meaning “Dutch studies.” These scholars were heavily influenced by Dutch industrial and scientific thinking. The Shimazu were particularly influenced by the Rangaku Dutch studies, and they were given the Shogun’s blessing to send a small number of scholars and generals aboard V.O.C. ships to see the extent of the Dutch Empire, and their advanced factories. Primarily, wishing to assess and spy on the western powers, the Dutch were more than happy to flaunt their wealth and prestige. The scholars were both astonished and disgusted by the machines used by the Dutch. A factory produced by the Dutch could stamp out a hundred sword bayonets in a day, while a master artisan took months to forge a small batch of katana. Lacking the spirit and mastery, the scholars learned that the bayonet’s poor quality was of little consequence, as the Dutch won their wars from the barrel of a gun, and with high explosives. Warrior spirit, which traveling Samurai found in the warriors of India, were distressed to see that half a continent, one far larger and more populous than the island of Japan had been pushed to the brink of complete domination by a nation with guns instead of spirit and explosives instead of honour.

The scholars were both astonished and disgusted by the machines used by the Dutch. A factory produced by the Dutch could stamp out a hundred sword bayonets in a day, while a master artisan took months to forge a small batch of katana. Lacking the spirit and mastery, the scholars learned that the bayonet’s poor quality was of little consequence, as the Dutch won their wars from the barrel of a gun, and with high explosives. Warrior spirit, which traveling Samurai found in the warriors of India, were distressed to see that half a continent, one far larger and more populous than the island of Japan had been pushed to the brink of complete domination by a nation with guns instead of spirit and explosives instead of honour.

A few craftsmen practicing the traditional means of sword smithing in modern day Japan. The art was kept alive by enthusiasts, collectors and the government over centuries of modernization.

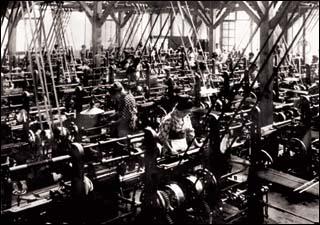

The small group of Japanese travelers and scholars had taken several lessons of Dutch science and progress to heart, and attempted to create their own industrial complex in Kagoshima. This first factory was produced as a silk weaving factory using the European cotton processing technology, and was a complete failure. Their inability to adapt to the specific needs of the material caused endless problems, jams and breakdowns to the machines. Their second attempt, also funded by the Shimazu was more controversial in the eyes of the Shogun. The second was a cast iron factory.

The small group of Japanese travelers and scholars had taken several lessons of Dutch science and progress to heart, and attempted to create their own industrial complex in Kagoshima. This first factory was produced as a silk weaving factory using the European cotton processing technology, and was a complete failure. Their inability to adapt to the specific needs of the material caused endless problems, jams and breakdowns to the machines. Their second attempt, also funded by the Shimazu was more controversial in the eyes of the Shogun. The second was a cast iron factory.

The Kagoshima silkworks, though a failure, were later made into a cotton producing facility receiving shipments from the west coast of the Dutch controlled Americas through Panama.

Under normal circumstances, this would not have been a tremendous problem, but in defiance of the Shogun’s decree against the manufacture of guns, the factory set about producing Dutch style fire arms using machined parts. Since the end of the Imjin war against Korea, the Tokugawa Shogunate had closely monitored possession and production of fire arms. Now with their ability to produce muskets by the hundred, the Shimazu were in clear defiance of the Shogun.

Under normal circumstances, this would not have been a tremendous problem, but in defiance of the Shogun’s decree against the manufacture of guns, the factory set about producing Dutch style fire arms using machined parts. Since the end of the Imjin war against Korea, the Tokugawa Shogunate had closely monitored possession and production of fire arms. Now with their ability to produce muskets by the hundred, the Shimazu were in clear defiance of the Shogun.

Contrary to popular belief, the Samurai had used, and had been adept in the use of guns prior to the 1700s. After the efficacy of the Matchlock in the Sengoku period, the Tokugawa Shogunate severely limited their production.

This wasn’t the first instance that European influence had led to a rebellion against the Shogun. In 1637, the Catholic population of Japan went into open revolt against the Shogun. The Amakusa, tired of religious oppression began what became known as the Shimabara rebellion. After their defeat, the Shogun expelled the Portuguese and Spanish from the country and outlawed Christianity. The Dutch, who had assisted the Shogun against the rebels were granted leave to remain so long as they did not observe any religious practice to Japan, did not attempt to sell Christian texts, and did not go outside of the port of Dejima.

This wasn’t the first instance that European influence had led to a rebellion against the Shogun. In 1637, the Catholic population of Japan went into open revolt against the Shogun. The Amakusa, tired of religious oppression began what became known as the Shimabara rebellion. After their defeat, the Shogun expelled the Portuguese and Spanish from the country and outlawed Christianity. The Dutch, who had assisted the Shogun against the rebels were granted leave to remain so long as they did not observe any religious practice to Japan, did not attempt to sell Christian texts, and did not go outside of the port of Dejima.

The ships at the bottom portion of this print are Dutch fighting on the side of the Shogun against the Catholics. They were asked to withdraw from the battle by the Shogun after the Amakusa questioned the honour of relying on mercenaries and merchants in combat.

This time however, the rebels were not the poorly funded and militarily weak Amakusa. The Shimazu were a stronger clan, with a long military history. Far from the reach of the Shogun and separated by the sea, the Shimazu were able to build up considerable force before they attempted to move openly against the Shogun.

This time however, the rebels were not the poorly funded and militarily weak Amakusa. The Shimazu were a stronger clan, with a long military history. Far from the reach of the Shogun and separated by the sea, the Shimazu were able to build up considerable force before they attempted to move openly against the Shogun.

The crest of the Shimazu.

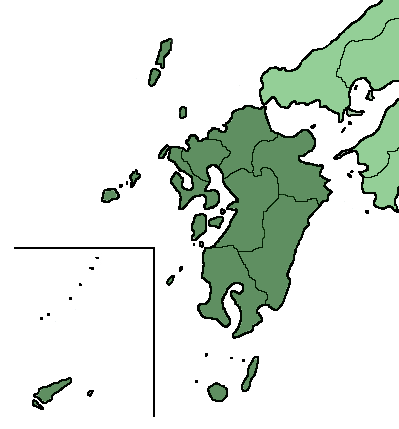

Shogunate forces were sent to dismantle the Kagoshima factory, which by 1745 had become a full industrial complex, as well as the local school which taught science, mathematics and philosophy in addition to the traditional Japanese arts. The Shimazu by then, hand conquered many of the southern islands of Japan. On the mainland, they would have faced considerable opposition, as the Tokugawa had established many policed and government maintained roads that would have allowed the much larger Shogun armies move with speed against the Shimazu. The islands however, required a strong navy, which the Japanese mainland lacked. The most adept sailors, the Mori were to make way to the Shimazu heartlands and put them their leaders to the sword.

Shogunate forces were sent to dismantle the Kagoshima factory, which by 1745 had become a full industrial complex, as well as the local school which taught science, mathematics and philosophy in addition to the traditional Japanese arts. The Shimazu by then, hand conquered many of the southern islands of Japan. On the mainland, they would have faced considerable opposition, as the Tokugawa had established many policed and government maintained roads that would have allowed the much larger Shogun armies move with speed against the Shimazu. The islands however, required a strong navy, which the Japanese mainland lacked. The most adept sailors, the Mori were to make way to the Shimazu heartlands and put them their leaders to the sword.

Kyushu, and the region controlled by the Shimazu and their allies.

The Mori arrived in Fukuoka in spring, having difficulty finding a safe landing area with the Shimazu cannons pointed towards many of the harbours around Kyushu. Having to wait until they could make a short crossing in the rain, when the relatively exposed cannons would have difficulty in keeping their powder dry, the Mori managed to make a rushed land fall without much incident with the Shimazu retreating their cannon out of the way of the Mori.

The Mori arrived in Fukuoka in spring, having difficulty finding a safe landing area with the Shimazu cannons pointed towards many of the harbours around Kyushu. Having to wait until they could make a short crossing in the rain, when the relatively exposed cannons would have difficulty in keeping their powder dry, the Mori managed to make a rushed land fall without much incident with the Shimazu retreating their cannon out of the way of the Mori. The Shimazu hadn’t abolished the military doctrine that they had acquired over the centuries in its entirety. While hundreds of peasants were armed with crude first print muskets from their new factories, hundreds more were armed with the more traditional long spear, and the Samurai went into battle with spears, swords and bows. As more and more guns could be produced, more of the men would be armed in the European fashion. The Mori were equipped with bows, spears and halberds much in the traditional style, as well as aged matchlocks from the previous war.

The Shimazu hadn’t abolished the military doctrine that they had acquired over the centuries in its entirety. While hundreds of peasants were armed with crude first print muskets from their new factories, hundreds more were armed with the more traditional long spear, and the Samurai went into battle with spears, swords and bows. As more and more guns could be produced, more of the men would be armed in the European fashion. The Mori were equipped with bows, spears and halberds much in the traditional style, as well as aged matchlocks from the previous war.

The modern line infantry were placed ahead of the Samurai, partly so the Shimazu could test them in battle.

The gun line of the Shimazu was somewhat poorly managed. Following Dutch doctrine, they were used as front line melee infantry against the oncoming Mori army. However, a factory defect meant their bayonets could not be locked in place, rendering the men virtually unarmed in melee combat. Using factory printed katana in melee instead, and with virtually no swordsmanship practice, the Shimazu peasants were quickly pushed back.

The gun line of the Shimazu was somewhat poorly managed. Following Dutch doctrine, they were used as front line melee infantry against the oncoming Mori army. However, a factory defect meant their bayonets could not be locked in place, rendering the men virtually unarmed in melee combat. Using factory printed katana in melee instead, and with virtually no swordsmanship practice, the Shimazu peasants were quickly pushed back.

Shimazu line infantry firing into the approaching Mori warriors. The oncoming mass had a profound impact on the poorly trained infantry's morale.

The battle had begun on a positive note, with the mortars scouring the field in front of them, killing hundreds as they closed in on the initial charge. The charge however, exacted immediate retribution, with the poorly equipped gunmen dying by the dozen.

The battle had begun on a positive note, with the mortars scouring the field in front of them, killing hundreds as they closed in on the initial charge. The charge however, exacted immediate retribution, with the poorly equipped gunmen dying by the dozen.

Howitzers firing explosive shells into the Samurai. By the 1740s, the Dutch were using a more delicate contact fuse on their high explosive shells making them far more deadly.

The battle was only saved when the heavy Shimazu cavalry made their way into the back lines of the Mori forces, causing a chain rout of the peasant soldiers. Unsupported, the few samurai of the Mori were surrounded and killed by the sword, bow and spear armed Shimazu samurai and ashigaru.

The battle was only saved when the heavy Shimazu cavalry made their way into the back lines of the Mori forces, causing a chain rout of the peasant soldiers. Unsupported, the few samurai of the Mori were surrounded and killed by the sword, bow and spear armed Shimazu samurai and ashigaru.

The Mori are pushed back and destroyed by the Shimazu forces.

The battle was not a clear cut victory for the industrialized Shimazu, and with a population base lower than that of the mainland, the Shimazu weren’t even in a position to completely replenish their army, having more weapons and ammunition than they could feasibly use in battle. Still, they consolidated their armies into a single force and departed in ships from Fukuoka to the main island of Honshu, cutting north to directly attack the spiritual capital of Japan, Kyoto. The Shogun’s personal fleet centered around the Nihon Maru was sunk in sea near Matsue under cannon fire from the more modern Shimazu fleet cleared the way for them to reach Kyoto.

The battle was not a clear cut victory for the industrialized Shimazu, and with a population base lower than that of the mainland, the Shimazu weren’t even in a position to completely replenish their army, having more weapons and ammunition than they could feasibly use in battle. Still, they consolidated their armies into a single force and departed in ships from Fukuoka to the main island of Honshu, cutting north to directly attack the spiritual capital of Japan, Kyoto. The Shogun’s personal fleet centered around the Nihon Maru was sunk in sea near Matsue under cannon fire from the more modern Shimazu fleet cleared the way for them to reach Kyoto.

The Nihon Maru was the pride of Japan, and the flag ship of the Shogunate. A veritable fortress on water, much like a modern castle, cannon fire was its undoing.

Claiming the assault was intended to place the Emperor back into his traditional seat of power, the small Shimazu force was stymied by the garrison that held Kyoto. The fortress of Kyoto had long been the formidable seat of power in Japan, but by the 1700s, real power had migrated to the city of Edo, the Shogunate capital. With that in mind, the army that defended Kyoto was not the strongest in Japan at the time, that army being confined to Edo directly under the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Claiming the assault was intended to place the Emperor back into his traditional seat of power, the small Shimazu force was stymied by the garrison that held Kyoto. The fortress of Kyoto had long been the formidable seat of power in Japan, but by the 1700s, real power had migrated to the city of Edo, the Shogunate capital. With that in mind, the army that defended Kyoto was not the strongest in Japan at the time, that army being confined to Edo directly under the Tokugawa Shogunate.

The outer courtyard of Kyoto castle. The walled outer courtyard was so large that conventional land battles complete with cavalry and artillery could be fought entirely enclosed by the fortifications.

The siege fielded with considerable artillery managed to push back many of the archers that would have otherwise rained down arrows into the advancing Shimazu infantry. Explosives, cannon fire and gun fire pushed the Shogunate forces onto the top of the castle. From there, the Shimazu continued to rain down explosive shells, arrow fire and gun fire as their samurai closed in on the walls, burned the gate houses and prepared for a coordinated assault.

The siege fielded with considerable artillery managed to push back many of the archers that would have otherwise rained down arrows into the advancing Shimazu infantry. Explosives, cannon fire and gun fire pushed the Shogunate forces onto the top of the castle. From there, the Shimazu continued to rain down explosive shells, arrow fire and gun fire as their samurai closed in on the walls, burned the gate houses and prepared for a coordinated assault.

The Shimazu are forced into a blazing choke point as the Tokugawa forces rally around their burning gate house. Shimazu forces circumvented the choke point in some places by scaling the walls.

The Shogun and the brunt of his forces were not defeated with the loss of Kyoto, and much of Japan had rallied against or with the Shimazu. The factory in the south of Japan had flourished into an industrial city, and many of their defects were corrected. However, as the Shimazu marched eastward to Edo, the Shogun was making his own preparations.

The Shogun and the brunt of his forces were not defeated with the loss of Kyoto, and much of Japan had rallied against or with the Shimazu. The factory in the south of Japan had flourished into an industrial city, and many of their defects were corrected. However, as the Shimazu marched eastward to Edo, the Shogun was making his own preparations. The Dutch at the start of the war, had backed off to a degree at Dejima, officially petitioning the Shogun and promising their support. While they still financed the Shimazu, the Dutch officially backed the Shogun under two concessions. One, the Shogun produce Dutch style factories and schools in Edo, Osaka and Yokohama, and that they open a new port similar to Dejima closer to the capital. In the end, the port was constructed in Nagoya.

The Dutch at the start of the war, had backed off to a degree at Dejima, officially petitioning the Shogun and promising their support. While they still financed the Shimazu, the Dutch officially backed the Shogun under two concessions. One, the Shogun produce Dutch style factories and schools in Edo, Osaka and Yokohama, and that they open a new port similar to Dejima closer to the capital. In the end, the port was constructed in Nagoya.

The Dutch district of Nagoya today.

The Shogun required considerable economic incentive to allow those concessions, but as the demilitarization policy had set thousands of samurai adrift for generations, many of whom were willing to work for the Shimazu as much as the Shogun, and the outdated matchlocks used by the shogunate forces were restricted to only a few gun smiths that could produce only a handful every year, leaving them far behind compared to the Shimazu. Indeed, what the Dutch were offering was not to sell arms to the Shogun, but the means for him to arm his own men on equal or superior terms to the Shimazu under government instituted buildings.

The Shogun required considerable economic incentive to allow those concessions, but as the demilitarization policy had set thousands of samurai adrift for generations, many of whom were willing to work for the Shimazu as much as the Shogun, and the outdated matchlocks used by the shogunate forces were restricted to only a few gun smiths that could produce only a handful every year, leaving them far behind compared to the Shimazu. Indeed, what the Dutch were offering was not to sell arms to the Shogun, but the means for him to arm his own men on equal or superior terms to the Shimazu under government instituted buildings. Of course, the Dutch had directed the Shogun to industries that required coal, iron and cotton. Commodities the Dutch were happy to provide at high prices, and which the Shogun could not acquire in sufficient numbers without them.

Of course, the Dutch had directed the Shogun to industries that required coal, iron and cotton. Commodities the Dutch were happy to provide at high prices, and which the Shogun could not acquire in sufficient numbers without them.

Cotton was lighter and cheaper than silk, and was cooler than wool making it a superior material for soldier's uniforms in the humidity and heat of Japan. Cotton uniforms were considered a "strategic resource" by the 1870.

The Shogun, wanting to save face and avoid admitting to foreign aid was forced into a pseudo industrial revolution. Claiming the factories and inventions had been created by the Shogun and his advisors, industry, science and Dutch studies had become a serious fad among the Japanese nobles. Industrialization and mechanization became standard facts of life in Japan.

The Shogun, wanting to save face and avoid admitting to foreign aid was forced into a pseudo industrial revolution. Claiming the factories and inventions had been created by the Shogun and his advisors, industry, science and Dutch studies had become a serious fad among the Japanese nobles. Industrialization and mechanization became standard facts of life in Japan. The Shimazu on the other hand had been forced to fight as though they had never industrialized. Without a stable supply line to their home ports, their ammunition and weapons had run dry, meaning the thousands of Samurai that filled their ranks were armed largely in the traditional style.

The Shimazu on the other hand had been forced to fight as though they had never industrialized. Without a stable supply line to their home ports, their ammunition and weapons had run dry, meaning the thousands of Samurai that filled their ranks were armed largely in the traditional style. With the aid of Dutch V.O.C. marines, the Japanese won a rousing victory against the Shimazu at Yokohama. Armed in the traditional manner, the Tokugawa army had moved forward cautiously against the Shimazu,watching as the Shimazu amassed their entire forces against the small line of Dutch V.O.C. The Dutch marines accounted for near to fifteen kills per man, standing in disciplined rows and firing into the far inferior Japanese line infantry. Though the Dutch line had been broken through, the late action of the Tokugawa arriving on the battered flanks caused the Shimazu to panic, resulting in a decisive win.

With the aid of Dutch V.O.C. marines, the Japanese won a rousing victory against the Shimazu at Yokohama. Armed in the traditional manner, the Tokugawa army had moved forward cautiously against the Shimazu,watching as the Shimazu amassed their entire forces against the small line of Dutch V.O.C. The Dutch marines accounted for near to fifteen kills per man, standing in disciplined rows and firing into the far inferior Japanese line infantry. Though the Dutch line had been broken through, the late action of the Tokugawa arriving on the battered flanks caused the Shimazu to panic, resulting in a decisive win.

The Dutch firing point blank into Japanese cavalry. The cavalry charge blunted, they were able to remain in a strong position by the time the Shimazu infantry came into contact with them.

The Shogun executed the leaders of the rebellion, and reneged on several Deals with the Dutch, withdrawing back into a state of seclusion, but the Shogun could not easily stave off increasing intellectualism within the Japanese populace. More and more of the merchant class found a way out of a vocation considered dishonourable by working in schools as scholars. No longer based on self denial and asceticism, many academies were focused on highly technical pursuits. This period of time would influence the Japanese greatly, and largely dictated their course for the next three hundred years.

The Shogun executed the leaders of the rebellion, and reneged on several Deals with the Dutch, withdrawing back into a state of seclusion, but the Shogun could not easily stave off increasing intellectualism within the Japanese populace. More and more of the merchant class found a way out of a vocation considered dishonourable by working in schools as scholars. No longer based on self denial and asceticism, many academies were focused on highly technical pursuits. This period of time would influence the Japanese greatly, and largely dictated their course for the next three hundred years.

A European style academy. The few of these schools allowed in Japan were taught by Japanese philosophers using Dutch texts, and many taught lectures in Dutch. Academy graduates often went on to found factories after graduation, as it was the most lucrative career a graduate could attain.

By the late 1700s, the V.O.C. had largely been pulled into the Dutch government itself, and then broken into thousands of independent companies. Part of this meant a sharp decrease in the Dutch influence of the far east during the 1800s. By 1820, Japan had gone into a state of complete seclusion, save for considerable expansion and trade on the mainland of Asia. For the most part, they would remain forgotten by the western world for the next two hundred years.

By the late 1700s, the V.O.C. had largely been pulled into the Dutch government itself, and then broken into thousands of independent companies. Part of this meant a sharp decrease in the Dutch influence of the far east during the 1800s. By 1820, Japan had gone into a state of complete seclusion, save for considerable expansion and trade on the mainland of Asia. For the most part, they would remain forgotten by the western world for the next two hundred years. But it was these formative years in the mid 1700s, at the peak of Dutch expansion and power that the Japanese were most heavily influenced. If it were not for these decades of scientific progress, obsession with Dutch technology and industrialization, the Japanese would have failed to become the technological menace that they were come the mid 1900s.

But it was these formative years in the mid 1700s, at the peak of Dutch expansion and power that the Japanese were most heavily influenced. If it were not for these decades of scientific progress, obsession with Dutch technology and industrialization, the Japanese would have failed to become the technological menace that they were come the mid 1900s.Next we will be presenting and atheist’s ideal Christmas. Following this, the reason to celebrate, or why it is important for communities to engage in communal ceremonies. World news has been moved back an hour for today and for the rest of the Christmas season. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

A note from our technical crew, this update to our web archives has been created using advanced visual hardware compared to previous broadcasts. Please tell us if you think the visual change is noticeable.