Part 33: February 9 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour there will be a special on picnicking in Britain, preparing for spring in Britain. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-third part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the sacking of London.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-third part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the sacking of London. The Dutch controlled London after the first siege of London, but they could not control England from London alone. Schafter eventually received sufficient intelligence from what agents he could send abroad, and from the barrister Arnold Drackenboch before deciding that his forces would have to withdraw from England or face destruction while trapped on hostile land. However, his troops would not be able or ready to move until spring the next year when the Dutch fleet would have a chance at breaking the blockade. He eventually decided to attempt his breakthrough through the limited defenses at Greenwich, as the British were heavily defending Portsmouth.

The Dutch controlled London after the first siege of London, but they could not control England from London alone. Schafter eventually received sufficient intelligence from what agents he could send abroad, and from the barrister Arnold Drackenboch before deciding that his forces would have to withdraw from England or face destruction while trapped on hostile land. However, his troops would not be able or ready to move until spring the next year when the Dutch fleet would have a chance at breaking the blockade. He eventually decided to attempt his breakthrough through the limited defenses at Greenwich, as the British were heavily defending Portsmouth.

Greenwich. England had many port cities, many of them still have a strong tie to boating for both entertainment and business.

The navy however, could not come ashore to capture or destroy the British fleet guarding Greenwich, as the December weather was fairly rough with rough winds blowing away from Greenwich. As they couldn’t have come to port until Schafter had pushed them out to sea, they wouldn’t be capable of evacuating regardless.

The navy however, could not come ashore to capture or destroy the British fleet guarding Greenwich, as the December weather was fairly rough with rough winds blowing away from Greenwich. As they couldn’t have come to port until Schafter had pushed them out to sea, they wouldn’t be capable of evacuating regardless.

Despite the small size of the English channel, the water could get very turbulent. The Dutch didn't want to sail their ships close into shore during the storm season.

Those months granted the British ample time to draw forces towards London. Without even time to repair the walls, the Dutch had a broken fortress to defend with a mere one and a half thousand men against near seven thousand British troops across England, but with the remaining fortifications, Schafter was confident that he could hold out until ships could be landed in spring. That many would survive was a different matter.

Those months granted the British ample time to draw forces towards London. Without even time to repair the walls, the Dutch had a broken fortress to defend with a mere one and a half thousand men against near seven thousand British troops across England, but with the remaining fortifications, Schafter was confident that he could hold out until ships could be landed in spring. That many would survive was a different matter.

British forces from across Britain converge on London. Schafter is outnumbered nearly three to one between the four British armies.

The British assault was organized by April and consisted of over four thousand men. Intending to block in the Dutch before they could depart, the British had enough men to attempt an assault on the walls rather than a siege. This gave the Dutch a brief glimmer of hope, as a siege would have required armies pulled from Amsterdam to relieve them. The British moved forward briskly, aware that there was a breach in the Dutch controlled walls, moving around the defenses towards the gap. The Dutch Holland guard had, in contravention of orders moved forward past the gap to form firing lines and then charge the advancing British forces, holding them up past the walls.

The British assault was organized by April and consisted of over four thousand men. Intending to block in the Dutch before they could depart, the British had enough men to attempt an assault on the walls rather than a siege. This gave the Dutch a brief glimmer of hope, as a siege would have required armies pulled from Amsterdam to relieve them. The British moved forward briskly, aware that there was a breach in the Dutch controlled walls, moving around the defenses towards the gap. The Dutch Holland guard had, in contravention of orders moved forward past the gap to form firing lines and then charge the advancing British forces, holding them up past the walls.

The blue guard defend a breach made when they had taken the fortress. The British would be focusing their assault on that breach.

The Dutch had not yet repaired the walls that had been battered in 1744, and so the Dutch blue guard were tasked with holding the gap in the central courtyard. Along the walls were the remaining Holland guard and line infantry, which were likely redundant as the British at that time had no interest in scaling the walls. Their plan was to draw the entirety of the Dutch forces into the breach and place additional forces to sneak around the flanks of the Dutch fortifications. Unopposed, those elements could either attack the defenders from the rear, or capture the fortress. Tasked with finding weaknesses along the Dutch walls were the Welsh Fusillier battalion, and the Scottish black watch, both formations which were tough and independent enough to cause severe damage alone.

The Dutch had not yet repaired the walls that had been battered in 1744, and so the Dutch blue guard were tasked with holding the gap in the central courtyard. Along the walls were the remaining Holland guard and line infantry, which were likely redundant as the British at that time had no interest in scaling the walls. Their plan was to draw the entirety of the Dutch forces into the breach and place additional forces to sneak around the flanks of the Dutch fortifications. Unopposed, those elements could either attack the defenders from the rear, or capture the fortress. Tasked with finding weaknesses along the Dutch walls were the Welsh Fusillier battalion, and the Scottish black watch, both formations which were tough and independent enough to cause severe damage alone.

Royal Welch Fusiliers. A grenadier battalion, they were an effective assault regiment.

Schaften had no real defensive plan. He knew that he would require the brunt of his forces at the breach, but that alone would be insufficient to fend off the British who would certainly exploit the situation by moving formations along the exposed and vulnerable Dutch walls. He was also keenly aware that his men would be firing at over three times their number in enemy infantry, meaning it was very probably that his forces would run dry of both shot and powder. Given the circumstances, he would have to improvise.

Schaften had no real defensive plan. He knew that he would require the brunt of his forces at the breach, but that alone would be insufficient to fend off the British who would certainly exploit the situation by moving formations along the exposed and vulnerable Dutch walls. He was also keenly aware that his men would be firing at over three times their number in enemy infantry, meaning it was very probably that his forces would run dry of both shot and powder. Given the circumstances, he would have to improvise.

While the Dutch kept a large magazine of powder, it was difficult to restock on powder in the middle of the battle, and they had only enough shot for the battle. While they could cast more after the battle, they didn't have the time or resources then.

Impetuous members of the Holland guard moved beyond the chokepoint of the walls to get early shots at the British force. Forming squares to receive their cavalry, and then pushing into the masses of British infantry, the foolish yet brave attack accounted for hundreds of British soldiers. They delayed six battalions of infantry and two battalions of cavalry for a substantial period of time, allowing the garrison along the walls ample time to take their shots into the far end of the melee ensuing below.

Impetuous members of the Holland guard moved beyond the chokepoint of the walls to get early shots at the British force. Forming squares to receive their cavalry, and then pushing into the masses of British infantry, the foolish yet brave attack accounted for hundreds of British soldiers. They delayed six battalions of infantry and two battalions of cavalry for a substantial period of time, allowing the garrison along the walls ample time to take their shots into the far end of the melee ensuing below.

Parts of the Dutch Holland guard sally forth to hold the British outside the walls. Over impetuous, the Dutch guard charged straight into the thick of things.

With the death of the forward elements of the Holland guard, the British managed to rush the breach. The gap was held by the Dutch Holland guard as well as the blue guard. Firing at the advancing troops, repelling them by the bayonet, and launching artillery shells into the masses, the British first assault was pushed back. The battle was as bloody as the Holland guard’s stand outside the walls, and the gap in the fortress was soon choked with corpses.

With the death of the forward elements of the Holland guard, the British managed to rush the breach. The gap was held by the Dutch Holland guard as well as the blue guard. Firing at the advancing troops, repelling them by the bayonet, and launching artillery shells into the masses, the British first assault was pushed back. The battle was as bloody as the Holland guard’s stand outside the walls, and the gap in the fortress was soon choked with corpses.

Firing by platoon, the shots into the British approaching the gap in the Dutch walls never ceased. As the left reloaded, the men to their right fired, and so on along the line. The constant, accurate fire of the guards accounted for thousands killed.

Even tied by the Dutch along the main breach, the British had managed to get a few battalions across the walls and into the central courtyard. The Royal Welsh Fusilliers managed to push over the Dutch walls and began firing at the Dutch artillery which had been firing over the walls. Dutch reserve infantry, Hussars and another line pulled from the gap were able to surround them and force them into flight, but a howitzer was taken out of the fight by the assault.

Even tied by the Dutch along the main breach, the British had managed to get a few battalions across the walls and into the central courtyard. The Royal Welsh Fusilliers managed to push over the Dutch walls and began firing at the Dutch artillery which had been firing over the walls. Dutch reserve infantry, Hussars and another line pulled from the gap were able to surround them and force them into flight, but a howitzer was taken out of the fight by the assault.

The Royal Welsh Fusiliers, caught in a vice in the London fortress. They managed to destroy a howitzer and ease the Dutch presence at the front, but were wiped out for their efforts.

The battle continued to wear on for hours. The Holland guard defending the gap were running low on munitions as were the blue guard. A few cursory assaults on the wall left of the breach were made, but to little result. The attacks however, forced the Dutch to station troops along the walls to repel attacks, which was what the British wanted. While the Dutch were able to evacuate most of their troops in time, several were killed when the wall collapsed, opening a second breach directly beside the first.

The battle continued to wear on for hours. The Holland guard defending the gap were running low on munitions as were the blue guard. A few cursory assaults on the wall left of the breach were made, but to little result. The attacks however, forced the Dutch to station troops along the walls to repel attacks, which was what the British wanted. While the Dutch were able to evacuate most of their troops in time, several were killed when the wall collapsed, opening a second breach directly beside the first.

The Holland guard had taken to the wall to defend against the black watch, but were forced to retreat back when the British blew the wall apart.

This opened up more for the British to attack, but at the same time, the Dutch had enough men remaining to push back their lines presenting a wider gun line around the breaches. The British hoped their advantage in numbers would let them smash through the choke point and sent in another wave of assailants, these coming faster than the previous ones. The Dutch were well situated to fire into the attackers, and managed to push them back, but by then, the Dutch were running out of ammunition. The blue guard and two battalions of the Holland guard had run dry as well.

This opened up more for the British to attack, but at the same time, the Dutch had enough men remaining to push back their lines presenting a wider gun line around the breaches. The British hoped their advantage in numbers would let them smash through the choke point and sent in another wave of assailants, these coming faster than the previous ones. The Dutch were well situated to fire into the attackers, and managed to push them back, but by then, the Dutch were running out of ammunition. The blue guard and two battalions of the Holland guard had run dry as well.

The Dutch expand their defensive line to fire into the two breaches. This gave them more firepower to deal with the multiple battalions assaulting from multiple angles, but at the same time, they were already running dry on ammunition. With more men fighting, more ammunition was expended.

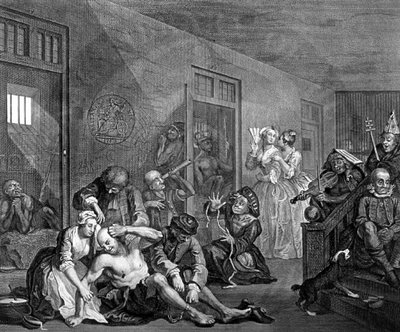

The battalion of line which still had munition withdrew in case they were needed at a later time while the guard charged the breach, meeting four British battalions. The guard fought valiantly, and while they were already well bloodied, they acquitted themselves well. It was said that the soldiers of the Dutch guard were heavily terrible, covered in blood from head to toe, and many after the horrors of the hours of conflict had gone utterly mad, and had fought like mad men. Such was the ferocity of their charge that the British infantry fell back before they had taken severe casualties.

The battalion of line which still had munition withdrew in case they were needed at a later time while the guard charged the breach, meeting four British battalions. The guard fought valiantly, and while they were already well bloodied, they acquitted themselves well. It was said that the soldiers of the Dutch guard were heavily terrible, covered in blood from head to toe, and many after the horrors of the hours of conflict had gone utterly mad, and had fought like mad men. Such was the ferocity of their charge that the British infantry fell back before they had taken severe casualties.

The Dutch guard, after hours of fighting, out of ammunition and near dead of exhaustion charge straight into the British line. Terrified of the Dutch guard, the British fall back.

That assault accounted for nearly all of the British infantry, granting the hussars an opportunity to destroy the British artillery trains which had been firing into the Dutch ceaselessly since the battle began. A detachment of infantry and the hussars crept out to bypass the melee along the gap, charging across the field, hitting the British artillery and the cavalry guarding them.

That assault accounted for nearly all of the British infantry, granting the hussars an opportunity to destroy the British artillery trains which had been firing into the Dutch ceaselessly since the battle began. A detachment of infantry and the hussars crept out to bypass the melee along the gap, charging across the field, hitting the British artillery and the cavalry guarding them.

The Hussars defeat the British artillery, now that the entire infantry line was drawn away. Their defeat marked the end of the battle, with the Dutch far too tired and weakened to continue chasing.

With that, the last of the British attackers in the second siege of London had ended. Schafter had lost nearly a thousand men, but had killed almost four thousand. The presence of fortifications and the power of the guard had made all the difference in regards to their ability to hold out against such a powerful attack.

With that, the last of the British attackers in the second siege of London had ended. Schafter had lost nearly a thousand men, but had killed almost four thousand. The presence of fortifications and the power of the guard had made all the difference in regards to their ability to hold out against such a powerful attack.

The second siege of London was one of the bloodiest in the war. Nearly the entire Dutch force had been wiped out, and thousands of British soldiers were dead.

Schafter likely suffered from post traumatic stress disorder after the battle. He and his forces had faced artillery fire for hours, and the fields had been choked with the stench of blood and death. Confined to such a small battlefield, the effects were multiplied, and as it had been merely Schafter’s second battle, and following four months of intense apprehension and stress, it was very likely that the battle changed him. He was nervous, and until the army was to be deployed back to Amsterdam through Greenwich, he had himself locked in London tower. When they did deploy, he wore the coat of a cavalryman rather than the accoutrement that a commanding officer was generally meant to wear, and looked about himself very fitfully the entire time.

Schafter likely suffered from post traumatic stress disorder after the battle. He and his forces had faced artillery fire for hours, and the fields had been choked with the stench of blood and death. Confined to such a small battlefield, the effects were multiplied, and as it had been merely Schafter’s second battle, and following four months of intense apprehension and stress, it was very likely that the battle changed him. He was nervous, and until the army was to be deployed back to Amsterdam through Greenwich, he had himself locked in London tower. When they did deploy, he wore the coat of a cavalryman rather than the accoutrement that a commanding officer was generally meant to wear, and looked about himself very fitfully the entire time.

The tower of London was more a prison than anything else at the time. He locked himself in it because the rooms in the Somerset house were a bit more open, letting him see the city that hated him.

By Spring however, the breeze still pushed away from the harbour at Greenwich, and the seas were rough which meant the Dutch ships would have to fight into the wind. To accommodate this, the Eerste Edelle, the Dutch steam ship was sent. This would be her first main engagement in which she was an active combatant.

By Spring however, the breeze still pushed away from the harbour at Greenwich, and the seas were rough which meant the Dutch ships would have to fight into the wind. To accommodate this, the Eerste Edelle, the Dutch steam ship was sent. This would be her first main engagement in which she was an active combatant.

The Dutch steam ship, the SS Eerste Edelle.

The Dutch fleet led by their steam ship moved into port as the remnants of Schafter’s army pushed into Greenwich. With no army present in Greenwich, the navy was forced into sea where the Dutch lay in wait. With the harbour secure, even before the British fleet was destroyed, the Dutch were preparing to embark upon their ships.

The Dutch fleet led by their steam ship moved into port as the remnants of Schafter’s army pushed into Greenwich. With no army present in Greenwich, the navy was forced into sea where the Dutch lay in wait. With the harbour secure, even before the British fleet was destroyed, the Dutch were preparing to embark upon their ships.

The British fleet forced out into the sea by the Dutch forces. Sailing with the wind, and the Dutch against it, they hoped to break to the north and catch a trade wind before the Dutch ships could catch up to them.

The British fleet guarding Greenwich was thankfully minimal, a fact which had helped the Dutch in deciding where they would retreat through. With a brisk wind behind them, and rough seas, the ships hope to break past the Dutch ships and make for Ireland. Assuming the Dutch would not be capable of catching the light brigs while sailing into the wind, the British made way as quickly as possible.

The British fleet guarding Greenwich was thankfully minimal, a fact which had helped the Dutch in deciding where they would retreat through. With a brisk wind behind them, and rough seas, the ships hope to break past the Dutch ships and make for Ireland. Assuming the Dutch would not be capable of catching the light brigs while sailing into the wind, the British made way as quickly as possible. The Dutch fleet led by the Eerste Edelle pushed forward as best they could. The British were put onto the back heel by their movement, and were forced to turn and fight. As they rounded Britain and began to move north and west, they knew the Dutch ships would gain on them as they lost the wind. They could attempt to run to Sweden, wait for more favourable winds and sail to Ireland from Greenland, but they would have to bypass two more fleets to do so, both of which had decent odds of capturing them.

The Dutch fleet led by the Eerste Edelle pushed forward as best they could. The British were put onto the back heel by their movement, and were forced to turn and fight. As they rounded Britain and began to move north and west, they knew the Dutch ships would gain on them as they lost the wind. They could attempt to run to Sweden, wait for more favourable winds and sail to Ireland from Greenland, but they would have to bypass two more fleets to do so, both of which had decent odds of capturing them.

The British and Dutch clash. The British hope to break past them by skirting to the North side of the British fleet heading east, then north again away from the Dutch ships.

The Eerste Edelle while severely under gunned by contrast to a heavier vessel had a thick hull, one that was capable of preventing it from taking significant damage from the lighter British ships. The lead and iron shot was insufficient to defeat the steel reinforced boiler that took up a great deal of the ships mid section, and the hull had been constructed with far greater strength to withstand the strain that the paddlewheels exerted on the overall structure. Cannon fire bounced off the wooden hull as she advanced towards them.

The Eerste Edelle while severely under gunned by contrast to a heavier vessel had a thick hull, one that was capable of preventing it from taking significant damage from the lighter British ships. The lead and iron shot was insufficient to defeat the steel reinforced boiler that took up a great deal of the ships mid section, and the hull had been constructed with far greater strength to withstand the strain that the paddlewheels exerted on the overall structure. Cannon fire bounced off the wooden hull as she advanced towards them.

The steam ship design was robust, and would lead to an arms race of high power guns in the 1800s, rather than an increase in the number of cannons.

As the entire British line was forced to turn and fight, the Eerste Edelle slowed her engines to allow the rest of her fleet to regroup to her, just ensuring to keep a steady distance to prevent the British from running. Once the fleet had regrouped, they came down upon the brigs destroying them quickly and efficiently. The steam ship proved its worth by blowing several of the light ships apart. While she had thirty guns, they were of a much heavier caliber than the ones upon the brigs allowing a greater amount of penetration.

As the entire British line was forced to turn and fight, the Eerste Edelle slowed her engines to allow the rest of her fleet to regroup to her, just ensuring to keep a steady distance to prevent the British from running. Once the fleet had regrouped, they came down upon the brigs destroying them quickly and efficiently. The steam ship proved its worth by blowing several of the light ships apart. While she had thirty guns, they were of a much heavier caliber than the ones upon the brigs allowing a greater amount of penetration.

The Dutch fleet managed to struggle their way up to the steam ship and the British brigs. The Eerste Edelle always kept close enough to the British to prevent flight. When contact was finally made, the British brigs were easily dispatched.

With the fleet destroyed, the Dutch ferries managed to pull into Greenwich and evacuate the forces of Schaften. Arriving in Calais, then Rotterdam, Schaften and the guard were secreted back to the Hague, where the Dutch had intended to keep their withdrawal under wraps, at least until they could put a positive twist to the events that transpired. Shortly after the withdrawal from Greenwich, another two thousand British soldiers retook London, a sum of soldiers which would have certainly overwhelmed the few hundred defenders left to Schaften.

With the fleet destroyed, the Dutch ferries managed to pull into Greenwich and evacuate the forces of Schaften. Arriving in Calais, then Rotterdam, Schaften and the guard were secreted back to the Hague, where the Dutch had intended to keep their withdrawal under wraps, at least until they could put a positive twist to the events that transpired. Shortly after the withdrawal from Greenwich, another two thousand British soldiers retook London, a sum of soldiers which would have certainly overwhelmed the few hundred defenders left to Schaften.

The trip to Calais was faster than the trip to Rotterdam. The ships stopped at Calais first to weather out the last of the rough winter storm before progressing to Rotterdam.

The press had still believed London to be in the hands of the Dutch, and the Dutch people were not accustomed to defeat. While rumour had eventually gotten out and was put to the forefront of attention from the gutter press, the government was at a loss as to what to do. Schaften, touted hero of the battle was a wreck, Crieckenbeeck was dead, and the guard was down to a tenth of their full strength.

The press had still believed London to be in the hands of the Dutch, and the Dutch people were not accustomed to defeat. While rumour had eventually gotten out and was put to the forefront of attention from the gutter press, the government was at a loss as to what to do. Schaften, touted hero of the battle was a wreck, Crieckenbeeck was dead, and the guard was down to a tenth of their full strength.

While he would never set foot into one himself, Schafter's family created several asylums with slightly greater oversight and slightly better conditions than the bedlam houses that were the then-current refuge for the mad.

From a strategic overview, London was a Dutch success. The Dutch could draw upon far more men than the British could in a far shorter time to replace the massive losses they had suffered, and the British army had suffered a total of seven thousand casualties whereas the Dutch and their four thousand casualties. The British were left with perhaps two thousand men from across the isles, but the Dutch had at least five thousand left on Europe, theoretically to guard the mainland.

From a strategic overview, London was a Dutch success. The Dutch could draw upon far more men than the British could in a far shorter time to replace the massive losses they had suffered, and the British army had suffered a total of seven thousand casualties whereas the Dutch and their four thousand casualties. The British were left with perhaps two thousand men from across the isles, but the Dutch had at least five thousand left on Europe, theoretically to guard the mainland.

The British and Dutch armies faced off once more from across the channel. Dutch forces now outnumbered the British, but were not confident that the Swedish would not attack them if they left Amsterdam bare.

Invading with those forces would be risky, but with the press slowly coming around to calling the coalition government’s competence into question, the Dutch were forced into a corner. While the best of their army had suffered horrendous casualties, and Schaften was next to useless in his current state, the guard had retreated to Amsterdam. Though down to only a few hundred men from a full regiment, the remaining guard would form a nucleus for the guard to be rebuilt, though many of them were in a state much like Schaften.

Invading with those forces would be risky, but with the press slowly coming around to calling the coalition government’s competence into question, the Dutch were forced into a corner. While the best of their army had suffered horrendous casualties, and Schaften was next to useless in his current state, the guard had retreated to Amsterdam. Though down to only a few hundred men from a full regiment, the remaining guard would form a nucleus for the guard to be rebuilt, though many of them were in a state much like Schaften. London was in a state much like Amsterdam. London was retaken less than a year from its sacking, and the British army had pushed the Dutch off of Britain completely. While the populace at large celebrated the reclamation of London, the government was in a state of extreme consternation. They were aware of just how few men they had remaining, how much damage economic or otherwise the Dutch had caused, and the large number of Dutch soldiers remaining on Europe. Government information to the public was scarce and carefully phrased when it was released, and the press was kept tightly under heel. Tightly wound up, the Dutch and British were on the brink of yet another battle. The tremendous number of casualties suffered by the British had swung the odds highly in favour of the Dutch.

London was in a state much like Amsterdam. London was retaken less than a year from its sacking, and the British army had pushed the Dutch off of Britain completely. While the populace at large celebrated the reclamation of London, the government was in a state of extreme consternation. They were aware of just how few men they had remaining, how much damage economic or otherwise the Dutch had caused, and the large number of Dutch soldiers remaining on Europe. Government information to the public was scarce and carefully phrased when it was released, and the press was kept tightly under heel. Tightly wound up, the Dutch and British were on the brink of yet another battle. The tremendous number of casualties suffered by the British had swung the odds highly in favour of the Dutch. Next we’ll be visiting some of the best parks for spring picnics in Britain. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we’ll be visiting some of the best parks for spring picnics in Britain. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.