Part 34: February 12 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, professor Bogart will be discussing the etymology of Britain’s most common names. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-fourth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the retreat from London.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-fourth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the retreat from London. Dutch forces were severely depleted, and would take a year to fully recover the guard. It would take another six months to arrange another landing, and assuming the British could cover the port of Greenwich, another six months to actually invade.

Dutch forces were severely depleted, and would take a year to fully recover the guard. It would take another six months to arrange another landing, and assuming the British could cover the port of Greenwich, another six months to actually invade.

Without a direct port to 'Britain, the Dutch would not be capable of a succesful or rapid landing.

In Britain, it would take a year to re-establish their own guard, and the additional year before invasion would let them recruit at least a thousand more men from across Britain. This would mean the Dutch would have to send men from France and additional forces from Amsterdam to match the British forces, but since the Dutch had defeated near twice as many men in Britain as they had lost, the Dutch could possibly have conquered Britain even with England’s greater recruitment window.

In Britain, it would take a year to re-establish their own guard, and the additional year before invasion would let them recruit at least a thousand more men from across Britain. This would mean the Dutch would have to send men from France and additional forces from Amsterdam to match the British forces, but since the Dutch had defeated near twice as many men in Britain as they had lost, the Dutch could possibly have conquered Britain even with England’s greater recruitment window.

While the streets of London and Edinburgh were filled with men suitable for combat, Paris, Vienna, Amsterdam, and Seville had far more. Even with a year to recruit men which would not be available to the Dutch, Britain could not hope to match the Dutch recruitment from across their empire.

Britain knew they had scant few years to make their preparations, and part of their strategy was trying to garner allies to attack the Dutch. They had only one year to try and draw Dutch forces away from Britain, but by 1757, allies willing to aid the British cause were running short. Fewer still were willing to stir up trouble with the Dutch on their own indignation.

Britain knew they had scant few years to make their preparations, and part of their strategy was trying to garner allies to attack the Dutch. They had only one year to try and draw Dutch forces away from Britain, but by 1757, allies willing to aid the British cause were running short. Fewer still were willing to stir up trouble with the Dutch on their own indignation. The only nation besides the British officially at war with the Dutch by 1757 were the Quebecois in Canada. In essence, the intact colonial government of Quebec and Montreal of France, which had long hated the Dutch, and which had not existed at a time where it was proper to hate the British, had declared war with the Western Atlantic Federation as their attacks northward began to encroach on their territory. While the majority of the fighting up to that point in time had been conducted by the Portuguese, the government of Quebec had been promised Ireland if they could draw a large army away from Europe. They were hoping the Quebecois would manage to draw at least two thousand men to defend against a large scale assault from Montreal to Albany then further.

The only nation besides the British officially at war with the Dutch by 1757 were the Quebecois in Canada. In essence, the intact colonial government of Quebec and Montreal of France, which had long hated the Dutch, and which had not existed at a time where it was proper to hate the British, had declared war with the Western Atlantic Federation as their attacks northward began to encroach on their territory. While the majority of the fighting up to that point in time had been conducted by the Portuguese, the government of Quebec had been promised Ireland if they could draw a large army away from Europe. They were hoping the Quebecois would manage to draw at least two thousand men to defend against a large scale assault from Montreal to Albany then further.

Quebec was modeled around the large European cities of the day, with large stone structures which would not look out of place in Europe today. Many citizens of Quebec lived in a fairly European style, and their politicians spent a considerable amount of time in France, despite the ongoing war with the Dutch. Keeping abreast of fashion from abroad was a priority for the wealthy.

What Britain wasn’t aware of was that the Dutch had not moved their entire North American force back to Amsterdam, and worse still, they had severely underestimated the Portuguese who were in control of much of Eastern Canada. While the Dutch were relatively static in the North American theater, uninterested in conquering Quebec and Montreal, the Dutch had left the battles to the conquering Portuguese. However, the Dutch had noted a movement of several thousand troops massed just North of the Saint Lawrence River prompting them to move their forces towards Montreal.

What Britain wasn’t aware of was that the Dutch had not moved their entire North American force back to Amsterdam, and worse still, they had severely underestimated the Portuguese who were in control of much of Eastern Canada. While the Dutch were relatively static in the North American theater, uninterested in conquering Quebec and Montreal, the Dutch had left the battles to the conquering Portuguese. However, the Dutch had noted a movement of several thousand troops massed just North of the Saint Lawrence River prompting them to move their forces towards Montreal.

The St. Lawrence River required almost the same logistics to cross as the ocean. Quebec forces were searching along it to find a point where they could cross without the Dutch defending. Fishermen reported the movement to the Dutch, and prompted a Dutch mobilization.

At the same time, the Portuguese began moving from Ontario to sack Quebec city, leaving the Quebecois government in a very difficult situation. Unable to defend either upper or lower Canada, the Quebec government was faced with complete destruction without any reprieve from the British. They appealed to have their government relocated to Ireland, as they had in fact been assaulted by well over two thousand Dutch soldiers. However, as they had done nothing to draw Dutch forces which were located in Europe to the Americas, the British reneged on the deal.

At the same time, the Portuguese began moving from Ontario to sack Quebec city, leaving the Quebecois government in a very difficult situation. Unable to defend either upper or lower Canada, the Quebec government was faced with complete destruction without any reprieve from the British. They appealed to have their government relocated to Ireland, as they had in fact been assaulted by well over two thousand Dutch soldiers. However, as they had done nothing to draw Dutch forces which were located in Europe to the Americas, the British reneged on the deal.

This pretty much entirely explains everything you need to know about Canada.

And so the Dutch had their forces assault Montreal without having to delay their second invasion onto British soil. The Portuguese were much less cautious than the Dutch forces, and so made their way through Quebec after horrendous casualties. Their invading force had been reduced to a few hundred men, but had taken control of the city, at which point they moved to assist the Dutch at Montreal.

And so the Dutch had their forces assault Montreal without having to delay their second invasion onto British soil. The Portuguese were much less cautious than the Dutch forces, and so made their way through Quebec after horrendous casualties. Their invading force had been reduced to a few hundred men, but had taken control of the city, at which point they moved to assist the Dutch at Montreal.

The Dutch and Portuguese move to sack Montreal. The Quebecois force retreating from the capital was intercepted before they could meet up with the main garrison.

The Dutch had moved with more caution first encountering and defeating a small group of Quebec soldiers which were attempting to regroup at Montreal, retreating from Quebec. The Dutch moved their army towards that force, cutting it off and destroying it piecemeal before moving towards the city proper. The defensive garrison, tied in Montreal trying to prepare field fortifications were unable to move their forces to reinforce.

The Dutch had moved with more caution first encountering and defeating a small group of Quebec soldiers which were attempting to regroup at Montreal, retreating from Quebec. The Dutch moved their army towards that force, cutting it off and destroying it piecemeal before moving towards the city proper. The defensive garrison, tied in Montreal trying to prepare field fortifications were unable to move their forces to reinforce.

The Dutch moving into position to attack the smaller Quebec force.

This small force was quickly quashed by the Dutch army, leaving the much more powerful Montreal force to defend against the Dutch and Portuguese forces.

This small force was quickly quashed by the Dutch army, leaving the much more powerful Montreal force to defend against the Dutch and Portuguese forces.

The Quebec forces needed every man they could get to try and resist the Dutch assault, and so the loss of their retreating forces was a critical blow.

The Dutch at Montreal were to attack directly while a small disruptive force of Portuguese sharpshooters and artillery attacked the Quebec forces from behind, hopefully pulling them away from their fortifications. Montreal did not have proper fortresses to stop the Dutch from attacking the city directly, and so an artillery assault from behind was far more debilitating than it would be in any other siege situation.

The Dutch at Montreal were to attack directly while a small disruptive force of Portuguese sharpshooters and artillery attacked the Quebec forces from behind, hopefully pulling them away from their fortifications. Montreal did not have proper fortresses to stop the Dutch from attacking the city directly, and so an artillery assault from behind was far more debilitating than it would be in any other siege situation.

The Dutch turn their attention to the brunt of the remaining Quebecois forces.

The Dutch lines deployed slightly beyond cannon range, advancing with their infantry in a line to the right away from the townhouses and buildings which were being used the quarter and arm the Quebec army. Once again, the Dutch moved their melee oriented native auxiliaries, still drawn from members of the South American tribes moved through the city streets to avoid enemy fire, while the Dutch line infantry moved to keep in the open, and their artillery kept to the far right flank, away from the cities and near the hills.

The Dutch lines deployed slightly beyond cannon range, advancing with their infantry in a line to the right away from the townhouses and buildings which were being used the quarter and arm the Quebec army. Once again, the Dutch moved their melee oriented native auxiliaries, still drawn from members of the South American tribes moved through the city streets to avoid enemy fire, while the Dutch line infantry moved to keep in the open, and their artillery kept to the far right flank, away from the cities and near the hills.

Faintly seen from the Dutch position were wisps of smoke from the Portuguese cannon.

The Dutch were advancing quickly, but the Portuguese had come to the back ranks too quickly. While they succeeded in drawing the Quebec forces away from their fortifications, and more importantly, leaving their artillery critically exposed, the Portuguese cannons and light infantry were rapidly overrun. Their army was essentially sent to be run off, and the small force managed to flee.

The Dutch were advancing quickly, but the Portuguese had come to the back ranks too quickly. While they succeeded in drawing the Quebec forces away from their fortifications, and more importantly, leaving their artillery critically exposed, the Portuguese cannons and light infantry were rapidly overrun. Their army was essentially sent to be run off, and the small force managed to flee.

The Quebec lines abandon their fortifications.

By the time the Quebec forces managed to rearranged themselves to fight the Dutch, their cannon had been overrun on their left flank, and the Dutch had advanced their forces directly to the Quebecois defensive fortifications. Moving back to assault the Dutch, their forces expanded on their right flank to envelope the Dutch left, moving through the thick trees just outside their base.

By the time the Quebec forces managed to rearranged themselves to fight the Dutch, their cannon had been overrun on their left flank, and the Dutch had advanced their forces directly to the Quebecois defensive fortifications. Moving back to assault the Dutch, their forces expanded on their right flank to envelope the Dutch left, moving through the thick trees just outside their base.

Dutch lines are outflanked on the left.

This left them within close striking distance to the native auxiliaries however, which charged from the city streets and into the infantry, pushing the flanking force away from the battlefield. Pushing their way past the Quebecois right flank, they managed to charge into the remaining Quebec artillery. This left Dutch forces in a strong position as their cannon fired shrapnel shot into the Quebecois lines, while their own line infantry moved to match them. With the addition of Dutch natives attacking along their flank in melee, the Quebec forces were finding themselves pressured along the flank, and eventually the remainder of their forces collapsed.

This left them within close striking distance to the native auxiliaries however, which charged from the city streets and into the infantry, pushing the flanking force away from the battlefield. Pushing their way past the Quebecois right flank, they managed to charge into the remaining Quebec artillery. This left Dutch forces in a strong position as their cannon fired shrapnel shot into the Quebecois lines, while their own line infantry moved to match them. With the addition of Dutch natives attacking along their flank in melee, the Quebec forces were finding themselves pressured along the flank, and eventually the remainder of their forces collapsed.

The auxiliaries strike from the streets to clear away the Quebec right flank. This attack resulted in the final collapse of the Quebec garrison.

With the Dutch in control of Quebec and Montreal, the British were out of allies. Their next best hope, the Polish had declared war on them as well, and the Polish and Courlander fleets destroyed a fleet of ships meant to cover Greenwhich after a declaration of war from Poland. Due to power and intimidation, the Dutch now had few enemies, while the entire world hoped to take away England from Britain before the Dutch could claim it for their own.

With the Dutch in control of Quebec and Montreal, the British were out of allies. Their next best hope, the Polish had declared war on them as well, and the Polish and Courlander fleets destroyed a fleet of ships meant to cover Greenwhich after a declaration of war from Poland. Due to power and intimidation, the Dutch now had few enemies, while the entire world hoped to take away England from Britain before the Dutch could claim it for their own.

A Courland fleet moves in to finish off a British fleet after it had been damaged by the Polish forces.

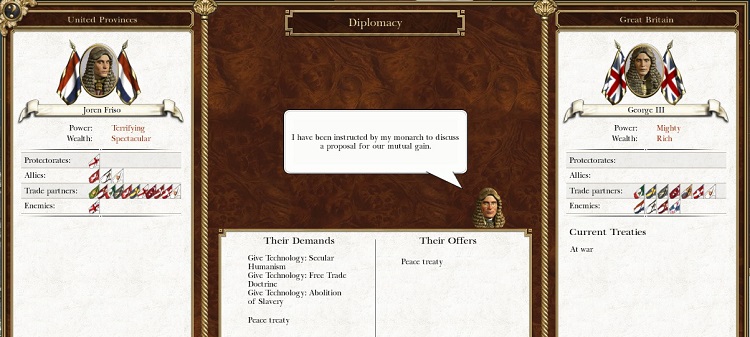

Britain however, was desperate. They needed more time to re-arm and prepare themselves for the battle which they knew was inevitable. While they knew that the Dutch forces would eventually attack regardless, they came to the negotiation table to attempt to gain a temporary ceasefire.

Britain however, was desperate. They needed more time to re-arm and prepare themselves for the battle which they knew was inevitable. While they knew that the Dutch forces would eventually attack regardless, they came to the negotiation table to attempt to gain a temporary ceasefire.

Britain had come to the table attempting to save face, making outrageous demands on the Dutch.

The Dutch, who had had forty years of ceaseless and pointless war with the British were caught off guard by this gesture, especially after they had lost London to the British. They were given essentially carte blanch on the terms, even though they had not acquired unconditional surrender, but needed time to assess the offer. Britain was willing to grant them full trade rights, Ireland, which was in a state of turmoil regardless, and at least five years of peace to be re-negotiated in four years.

The Dutch, who had had forty years of ceaseless and pointless war with the British were caught off guard by this gesture, especially after they had lost London to the British. They were given essentially carte blanch on the terms, even though they had not acquired unconditional surrender, but needed time to assess the offer. Britain was willing to grant them full trade rights, Ireland, which was in a state of turmoil regardless, and at least five years of peace to be re-negotiated in four years.

The Dutch had asked for Ireland, as well as unlimited trade rights. At first they had figured the British were mocking them with their harsh terms and offer, but when the British seriously considered accepting those terms, the Dutch were forced to look more closely at the offer.

The risk for the Dutch was that their time in office would end before the end of the ceasefire, meaning if the Orange party secured victory in the upcoming election, the Dutch may end up back at war with Britain. Such an event would be in part, desirable as the Dutch could practically taste victory, but at the same time, the entire point of the war had been to secure peace. While public opinion had been that the Dutch were doing well primarily because of their military conquests, at the same time, popular sentiment seemed to indicate the Dutch were optimistic that they were just another year from seeing the war end with peace, prosperity and victory. How would they react to just peace and prosperity?

The risk for the Dutch was that their time in office would end before the end of the ceasefire, meaning if the Orange party secured victory in the upcoming election, the Dutch may end up back at war with Britain. Such an event would be in part, desirable as the Dutch could practically taste victory, but at the same time, the entire point of the war had been to secure peace. While public opinion had been that the Dutch were doing well primarily because of their military conquests, at the same time, popular sentiment seemed to indicate the Dutch were optimistic that they were just another year from seeing the war end with peace, prosperity and victory. How would they react to just peace and prosperity? The Republican party was in a tight place. Turning down peace would inevitably be unpopular, but so would giving up the war. With more and more official announcements about the retreat from London, popularity for the Republicans was waning, and so this offer of peace was a very politically delicate situation.

The Republican party was in a tight place. Turning down peace would inevitably be unpopular, but so would giving up the war. With more and more official announcements about the retreat from London, popularity for the Republicans was waning, and so this offer of peace was a very politically delicate situation. By the end of negotiations, the Dutch did elect for a peaceful resolution. While it was played up as a British defeat which secured much in favour of the Dutch in reparations and land, the public opinion was mixed. Nationalists were furious that the Dutch had marched on to England and Scotland to take what they could through force. Many even believed that England was their right, and that allowing it to remain in a corrupted monarchy far removed from the rule of William the Third was heretical. The moderates however, believed that with peace secured at all fronts, the Dutch could finally look fully to civil matters, and that the Dutch trading companies could make millions off of trade with the British did not hurt to encourage many of those on the fence of the issue.

By the end of negotiations, the Dutch did elect for a peaceful resolution. While it was played up as a British defeat which secured much in favour of the Dutch in reparations and land, the public opinion was mixed. Nationalists were furious that the Dutch had marched on to England and Scotland to take what they could through force. Many even believed that England was their right, and that allowing it to remain in a corrupted monarchy far removed from the rule of William the Third was heretical. The moderates however, believed that with peace secured at all fronts, the Dutch could finally look fully to civil matters, and that the Dutch trading companies could make millions off of trade with the British did not hurt to encourage many of those on the fence of the issue.

While much reduced, Britain was still capable of outputting nearly ten million guilders in trade revenue to the Dutch every year. The British also profited greatly from the trade.

Ironically, by 1757, much of the Dutch industrial leaders, V.O.C. leaders and other business minded individuals had moved abroad, either to Paris, Cologne, India or the Americas. While several thousand who managed in insurance and stock trading had remained in the United Provinces themselves, the majority were men with a military or nationalist background. Several had gone so far as to decry the republican party as catering to other nations at the expensive of the United Provinces, leaving the Empire rich but the Emperors poor. This new generation of Dutch nationalists had not lived through Spanish persecution or rule, and few living could recall much of that time, and so the lessons of their past were not well remembered.

Ironically, by 1757, much of the Dutch industrial leaders, V.O.C. leaders and other business minded individuals had moved abroad, either to Paris, Cologne, India or the Americas. While several thousand who managed in insurance and stock trading had remained in the United Provinces themselves, the majority were men with a military or nationalist background. Several had gone so far as to decry the republican party as catering to other nations at the expensive of the United Provinces, leaving the Empire rich but the Emperors poor. This new generation of Dutch nationalists had not lived through Spanish persecution or rule, and few living could recall much of that time, and so the lessons of their past were not well remembered.

The Dutch long ago had fought to topple a regime which was similar to their own in many ways. The youths and leaders of the mid seventeen hundreds had pushed that from their minds as a new ideology took hold in many of the more militaristic among them.

After the past ten years as retired colonels, brigadiers and various other sorts flooded back in by the hundreds from India, America and Eastern Europe to Amsterdam, many becoming very active politically, the character of the average Dutch gentleman had begun to change. While years prior, it was the stockholder, the businessman or the factory owner, now it was the wealthy officer, either retired on a pension, or awaiting command of one of the many Dutch battalions which were in a perpetual state of paid stasis. With no wars left to be fought, they did little, but were necessary to deter war from potential enemies of the Dutch. Part of the upkeep and payment went to the austere appearing yet secretly lavish lifestyle of the typical Dutch army officer. While the men of their class may have been in puritanical clothes, the black silk, silver and golden army badges and expensive hats all spoke to a wealth which had to be shown only very subtly.

After the past ten years as retired colonels, brigadiers and various other sorts flooded back in by the hundreds from India, America and Eastern Europe to Amsterdam, many becoming very active politically, the character of the average Dutch gentleman had begun to change. While years prior, it was the stockholder, the businessman or the factory owner, now it was the wealthy officer, either retired on a pension, or awaiting command of one of the many Dutch battalions which were in a perpetual state of paid stasis. With no wars left to be fought, they did little, but were necessary to deter war from potential enemies of the Dutch. Part of the upkeep and payment went to the austere appearing yet secretly lavish lifestyle of the typical Dutch army officer. While the men of their class may have been in puritanical clothes, the black silk, silver and golden army badges and expensive hats all spoke to a wealth which had to be shown only very subtly.

All illusions of austerity were ignored entirely in government, where expensive art and decorations adorned the halls. The clothes of the average gentleman was relatively simple, but by no means affordable.

These men would bolster and strengthen the Orange party in the Netherlands, to the point where they were by far the most powerful domestic party. The Republicans kept control through their coalition with the V.O.C. which was well received the rest of the world over, but with more and more of their active military either retiring or idling in Amsterdam, more were turning to politics.

These men would bolster and strengthen the Orange party in the Netherlands, to the point where they were by far the most powerful domestic party. The Republicans kept control through their coalition with the V.O.C. which was well received the rest of the world over, but with more and more of their active military either retiring or idling in Amsterdam, more were turning to politics.

Even as the Dutch politics turned inward, their fleets continued to control the channel. The Dutch were not so foolish as to put their guard down.

While politics were busy pushing the Dutch through to a strange and unfamiliar time. They were in a short period of peace which seemed likely to lead to even greater lengths of peace as time wore on. Britain, in five years time would certainly not have the forces required to defeat the Dutch, now that the guard had returned to strength, that their forces in France had grown to a full scale army, and that Amsterdam had more forces by 1759 than they had when they first invaded. Combined, it seemed unlikely that Britain would renew hostilities when peace had run its course. Poland, now focused on blockading and harassing England, was drawn back into a war between themselves and Prussia, meaning hostilities could flare back to light in eastern Europe, but Poland was less than happy contemplating a war with a United Provinces which was not tied into a war in the west.

While politics were busy pushing the Dutch through to a strange and unfamiliar time. They were in a short period of peace which seemed likely to lead to even greater lengths of peace as time wore on. Britain, in five years time would certainly not have the forces required to defeat the Dutch, now that the guard had returned to strength, that their forces in France had grown to a full scale army, and that Amsterdam had more forces by 1759 than they had when they first invaded. Combined, it seemed unlikely that Britain would renew hostilities when peace had run its course. Poland, now focused on blockading and harassing England, was drawn back into a war between themselves and Prussia, meaning hostilities could flare back to light in eastern Europe, but Poland was less than happy contemplating a war with a United Provinces which was not tied into a war in the west.

Poland and Prussia renew their war. Prussia was but a shadow of their former glory, meaning the war could not last long.

Britain was certainly not in the clear by 1758. Though no longer at war with the Dutch, the worlds strongest Empire of the era, from invading their shores they did have to contend with Poland. While Poland was likely the third strongest, behind the Dutch and Ottoman Empires, they were still more than a match for Britain, so long as their boats could land ashore. It was only fortunate for Britain that the Polish were still in a state of unease against the Dutch, and so while Polish vessels patrolled the English channel, they were unwilling to move their armies away from the Dutch border.

Britain was certainly not in the clear by 1758. Though no longer at war with the Dutch, the worlds strongest Empire of the era, from invading their shores they did have to contend with Poland. While Poland was likely the third strongest, behind the Dutch and Ottoman Empires, they were still more than a match for Britain, so long as their boats could land ashore. It was only fortunate for Britain that the Polish were still in a state of unease against the Dutch, and so while Polish vessels patrolled the English channel, they were unwilling to move their armies away from the Dutch border.

A consequence of the peaceful period was that Schaften could safely retire without bringing disrepute to his name.

Next we’ll be looking at the etymological history of some of Britain’s most common names. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we’ll be looking at the etymological history of some of Britain’s most common names. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.