Part 35: February 15 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour Doctor O’Connell will be presenting interesting findings from Alaska on new Meteors discovered this past year. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-fifth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the ceasefire between Britain and the Dutch.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-fifth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the ceasefire between Britain and the Dutch. While a ceasefire does not guarantee lasting peace, and certainly does not imply that the nations involved were not still technically at war, it did give both sides incentive to reassess their position, their opponent and their goals, and after a half decade of considering their options while paying an idle army, peace became more and more likely.

While a ceasefire does not guarantee lasting peace, and certainly does not imply that the nations involved were not still technically at war, it did give both sides incentive to reassess their position, their opponent and their goals, and after a half decade of considering their options while paying an idle army, peace became more and more likely.

The Dutch send thousands of idle troops to both police Ireland, and to guard their acquisition from a British takeover. The last thing they wanted was the British to retake it from rebels, as it would invalidate the Dutch territorial rights.

Most politicians at the time were optimistic that the ceasefire would lead to a peace treaty before the end of their contract, and so the general tone was one of economic focus, but backed by military wariness. Especially along the Eastern Front, the Dutch were preparing themselves for the eventuality of a Polish invasion. However, at peace, and with less than a year between the ceasefire and 1758 election, the Dutch ministers had to insure that they were keeping the interest of the public.

Most politicians at the time were optimistic that the ceasefire would lead to a peace treaty before the end of their contract, and so the general tone was one of economic focus, but backed by military wariness. Especially along the Eastern Front, the Dutch were preparing themselves for the eventuality of a Polish invasion. However, at peace, and with less than a year between the ceasefire and 1758 election, the Dutch ministers had to insure that they were keeping the interest of the public. By the mid 1700s, the citizens of the Dutch Empire were on the whole, wealthier, better educated and more globally aware than they had ever been before. Keenly aware that nearly everyone within the Western Atlantic Federation had prospered due to the Dutch and the tremendous spending that had come to them from the Dutch, but at the same time, they knew that their supposedly free nations were heavily influenced or outright controlled by the Dutch.

By the mid 1700s, the citizens of the Dutch Empire were on the whole, wealthier, better educated and more globally aware than they had ever been before. Keenly aware that nearly everyone within the Western Atlantic Federation had prospered due to the Dutch and the tremendous spending that had come to them from the Dutch, but at the same time, they knew that their supposedly free nations were heavily influenced or outright controlled by the Dutch.

As places such as the palace of Versailles no longer had a steady income of tax revenue to fuel a monarchist's home, many were rented out to nobility who would congregate, talk politics, and use the opportunity to be seen with the local government.

This atmosphere bred a curious state where the intellectuals of the day spent considerable time talking about politics, political parties and of economics. Political talk and participating in politics had become a major pastime of the wealthy who were either patrons to the intellectuals, or where themselves philosophers and scholars. Following them were a great number of others who were significantly less intrigued by politics, but who greatly wished to remain as part of the times. The Germans refer to it as zeitgeist, and the zeitgeist of 1758 was one of political participation. Hundreds of third party political groups sprung up across the Empire, less to demonstrate any real political clout and far more to remain fashionable.

This atmosphere bred a curious state where the intellectuals of the day spent considerable time talking about politics, political parties and of economics. Political talk and participating in politics had become a major pastime of the wealthy who were either patrons to the intellectuals, or where themselves philosophers and scholars. Following them were a great number of others who were significantly less intrigued by politics, but who greatly wished to remain as part of the times. The Germans refer to it as zeitgeist, and the zeitgeist of 1758 was one of political participation. Hundreds of third party political groups sprung up across the Empire, less to demonstrate any real political clout and far more to remain fashionable.

In countries like Austria, the coffee house was also a major hub for intellectual discourse. Turkish styled coffee from the Ottoman trade partner of the Dutch was particularly popular.[/i]

This was effectively disastrous for the Republicans, as those smaller parties significantly diluted their vote. On the other hand, with thousands of officers returning home from the front lines to spend parts of their years away from the idle front lines, the Orange party was stronger than it had been in thirty years. Army officers, traditionalists, out of tune with fashion and often stoutly nationalist almost invariably voted for the Orange party, and their renewed presence at home and amid the politics gave the Orange party a near immovable bastion against the tiny parties which were picking apart the Republicans and V.O.C.

This was effectively disastrous for the Republicans, as those smaller parties significantly diluted their vote. On the other hand, with thousands of officers returning home from the front lines to spend parts of their years away from the idle front lines, the Orange party was stronger than it had been in thirty years. Army officers, traditionalists, out of tune with fashion and often stoutly nationalist almost invariably voted for the Orange party, and their renewed presence at home and amid the politics gave the Orange party a near immovable bastion against the tiny parties which were picking apart the Republicans and V.O.C.

Unlike the majority of the nobility, army officers demonstrated considerably greater solidarity which transferred over to politics.

To counteract this, the Republicans had dramatically improved economic spending. Many of the main old roads across both Europe and the East Coast of North America were built during this time as the Dutch put down hundreds of thousands of miles of metalled roads. These roads were smooth and durable, giving internal trade and supply far superior speed, and enabling resources to reach industry and towns which were otherwise out of reach. Overall, the ability to move materials and product rapidly helped improve the growing economy of the Empire as a whole, especially as industrial output was mostly required to fulfill the massive internal demand for the Empire.

To counteract this, the Republicans had dramatically improved economic spending. Many of the main old roads across both Europe and the East Coast of North America were built during this time as the Dutch put down hundreds of thousands of miles of metalled roads. These roads were smooth and durable, giving internal trade and supply far superior speed, and enabling resources to reach industry and towns which were otherwise out of reach. Overall, the ability to move materials and product rapidly helped improve the growing economy of the Empire as a whole, especially as industrial output was mostly required to fulfill the massive internal demand for the Empire.

Metalled road from the Dutch imperial age.

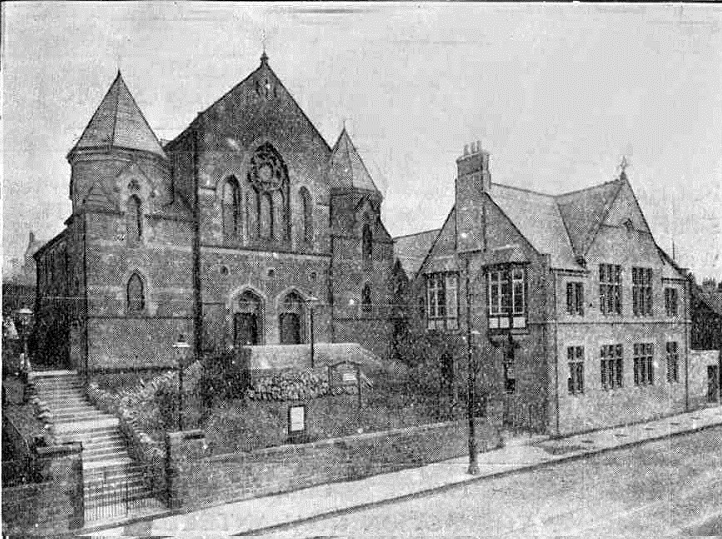

Besides roads, the Dutch also invested in hundreds of factories that they had at that point ignored. Even in towns traditionally noted for other specialties, especially those with beautiful and iconic churches, or universities found their former mainstay flooded by new, dirty factories. Those universities and churches either still exist to this day, were destroyed in the tumultuous times during the early to mid 1900s, or were restored as historical masterpieces. In the 1700s however, their importance was diminished, as aesthetics, religion and reason gave way to industry and wealth. As much as one could argue against such a path, the results were wealthier, better fed, healthier and often even happier people. It made the down to earth ideals of industrial success and economic success hard to argue against.

Besides roads, the Dutch also invested in hundreds of factories that they had at that point ignored. Even in towns traditionally noted for other specialties, especially those with beautiful and iconic churches, or universities found their former mainstay flooded by new, dirty factories. Those universities and churches either still exist to this day, were destroyed in the tumultuous times during the early to mid 1900s, or were restored as historical masterpieces. In the 1700s however, their importance was diminished, as aesthetics, religion and reason gave way to industry and wealth. As much as one could argue against such a path, the results were wealthier, better fed, healthier and often even happier people. It made the down to earth ideals of industrial success and economic success hard to argue against.

While a church had once been a centerpiece to a city, with grand buildings to overawe the remainder of the city, even a modest factory such as this could block out a church from the skyline, either from belching smoke, or their own blocky construction. The largest factory complexes were grand enough to overwhelm even famous churches, such as Westminster Abbey relied on the splendor and skill of the architecture rather than their size.

Of course, the workers themselves didn’t reap these benefits of society. Life in a factory could be outright Hobbesian, and the typical worker often found himself breathing rank, polluted air, water tainted by sewage and rats. Life in the lower class was fairly demoralizing, and while the wealthy and rich who avoided the rank lower streets while ruling the nation from on high, pressure had begun to boil from below.

Of course, the workers themselves didn’t reap these benefits of society. Life in a factory could be outright Hobbesian, and the typical worker often found himself breathing rank, polluted air, water tainted by sewage and rats. Life in the lower class was fairly demoralizing, and while the wealthy and rich who avoided the rank lower streets while ruling the nation from on high, pressure had begun to boil from below.

Life in factories and mines was nasty, brutish and short.

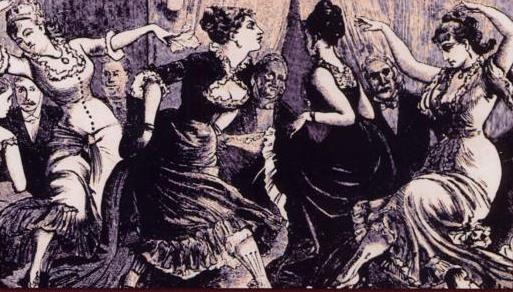

These pressures were released by a government fearful of rebellion, and unwilling to commit to oppressing the masses too heavily. Government sponsored brothels and places of ill repute were also funded during the mid 1700s, distilleries and breweries were paid as well as any other sector of industry so long as they agreed to keep their prices low in the poorer parts of town. There wasn’t much at all for the government to do in regards to keeping worker conditions in line, but they did institute minor fines to businesses which had an above average number of industrial deaths each month, and at the very least, the populace seemed content with their lot so long as the ale was plentiful and cheap, and prostitution was legal.

These pressures were released by a government fearful of rebellion, and unwilling to commit to oppressing the masses too heavily. Government sponsored brothels and places of ill repute were also funded during the mid 1700s, distilleries and breweries were paid as well as any other sector of industry so long as they agreed to keep their prices low in the poorer parts of town. There wasn’t much at all for the government to do in regards to keeping worker conditions in line, but they did institute minor fines to businesses which had an above average number of industrial deaths each month, and at the very least, the populace seemed content with their lot so long as the ale was plentiful and cheap, and prostitution was legal.

While the bawdy houses were technically created and funded by the government to placate the poor, the wealthy were not ones to miss out on a bit of discrete entertainment.

This elaborate spending of millions of guilders per year definitely did help the Dutch in controlling the populace, but as election loomed, it was clear it wasn’t doing enough. The republicans were forced to create yet another coalition government consisting of itself, the V.O.C. party, as well as five of the most influential minor parties. Those parties were the Historical Preservation society of Vienna, the Boston Representatives of North America, Schaften’s party (related to, but not led by General Schaften), the Royalist Party, and the Liberal Party.

This elaborate spending of millions of guilders per year definitely did help the Dutch in controlling the populace, but as election loomed, it was clear it wasn’t doing enough. The republicans were forced to create yet another coalition government consisting of itself, the V.O.C. party, as well as five of the most influential minor parties. Those parties were the Historical Preservation society of Vienna, the Boston Representatives of North America, Schaften’s party (related to, but not led by General Schaften), the Royalist Party, and the Liberal Party.

As official as they looked, this small group were not a major governing party. Such passive activism was considered socially fashionable, even if ineffective.

In the end, the Republicans controlled approximately thirty percent of the country, with the Orangists controlling just a few dozen votes more. However, the V.O.C. party controlled nearly ten percent of the vote, independants in the coalition another two, and the remainder had been wasted on small, largely irrelevant political parties.

In the end, the Republicans controlled approximately thirty percent of the country, with the Orangists controlling just a few dozen votes more. However, the V.O.C. party controlled nearly ten percent of the vote, independants in the coalition another two, and the remainder had been wasted on small, largely irrelevant political parties. This razor thin margin of victory forced the Dutch to continue along their path of industrial expansion even after the election. The new Republican ministers were not so foolish as to take their perilous government as strong enough to disappoint the populace. Spending remained constant in 1758 as compared to 1757, and would increase slightly over the next five years as the economy flourished during peace time.

This razor thin margin of victory forced the Dutch to continue along their path of industrial expansion even after the election. The new Republican ministers were not so foolish as to take their perilous government as strong enough to disappoint the populace. Spending remained constant in 1758 as compared to 1757, and would increase slightly over the next five years as the economy flourished during peace time.

The Dutch continue to pull more men from the fields and into factories. As the middle class grew, demand for product rose, but the Dutch were soon reaching the furthest their economy could stretch.

The Republicans were now led by Joordan Quintens. As the Stadtholder was a wartime office, he was moved to the back scenes of the Dutch government. While a moderately effective advocate for his party, he was largely irrelevant during his time in office.

The Republicans were now led by Joordan Quintens. As the Stadtholder was a wartime office, he was moved to the back scenes of the Dutch government. While a moderately effective advocate for his party, he was largely irrelevant during his time in office.

For once, the Statholder was not the leader of his party.

Joord Kieft, a fairly unremarkable man was made head of state, which during the 1760s was a primarily diplomatic office. His competence was put into question numerous times, but at the very least he didn’t start any wars as the Orange party had back in 1720.

Joord Kieft, a fairly unremarkable man was made head of state, which during the 1760s was a primarily diplomatic office. His competence was put into question numerous times, but at the very least he didn’t start any wars as the Orange party had back in 1720.

Kieft was a relatively unremarkable man, and got through his time in office primarily by delegating to more competent ministers. His own job, largely diplomatic in nature, was done with little to say of it.

Dirk Halse, the Dutch treasury minister was the representative of the V.O.C., and unlike the prior election, he was the only V.O.C. minister who had made it into office. One of their more talented ministers, Halse kept improving the Dutch economy, trade and spending. More than anything, he was a staunch supporter of efficient industry, and so many of the improvements and budgets done in his time in office were mostly based on his recommendations.

Dirk Halse, the Dutch treasury minister was the representative of the V.O.C., and unlike the prior election, he was the only V.O.C. minister who had made it into office. One of their more talented ministers, Halse kept improving the Dutch economy, trade and spending. More than anything, he was a staunch supporter of efficient industry, and so many of the improvements and budgets done in his time in office were mostly based on his recommendations.

Halse was the strongest of the V.O.C. candidates, and had backers from within the Republicans. He would have been a Republican if he wasn't a loyal company man.

His friend and Republican, Wim Wendels, who had strongly advocated for Halse was a similarly industrial man, but under his rule as minister of defense, conditions to maintain the army at its current state and professional standard were the priorities, and he needed to do so at minimal cost. As an industrial man himself, he enforced rulings stating that production of all military equipment was to be done in one several specific steam driven steel factories, and rifles, which required very specific caliber bullets could only be produced in any factory within ten hours of his office. By avoiding hand cast shot, he managed to encourage the production of mass produced shot from specialist factories, which sold it to him at low prices.

His friend and Republican, Wim Wendels, who had strongly advocated for Halse was a similarly industrial man, but under his rule as minister of defense, conditions to maintain the army at its current state and professional standard were the priorities, and he needed to do so at minimal cost. As an industrial man himself, he enforced rulings stating that production of all military equipment was to be done in one several specific steam driven steel factories, and rifles, which required very specific caliber bullets could only be produced in any factory within ten hours of his office. By avoiding hand cast shot, he managed to encourage the production of mass produced shot from specialist factories, which sold it to him at low prices.

Wendels was a man of many talents, but not necessarily of war. He was the very definition of a modern major general, but at the same time, his ability to organize and administrate the army through his various economic and administrative talents helped tremendously.

Wendels had made the latter ruling to allow complete standardization of the rifle’s shot and barrel size, which had to fit perfectly into a rifled musket. At that time and until the metric system was created in 1799, the Wendel Schot was the most heavily standardized unit of measure in the world, where instruments were designed to measure a shot to the standard size, which in metric would be 1.905 centimeters. His personal staff would ride out nearly every day to the various workshops to ensure that they were upholding those standards.

Wendels had made the latter ruling to allow complete standardization of the rifle’s shot and barrel size, which had to fit perfectly into a rifled musket. At that time and until the metric system was created in 1799, the Wendel Schot was the most heavily standardized unit of measure in the world, where instruments were designed to measure a shot to the standard size, which in metric would be 1.905 centimeters. His personal staff would ride out nearly every day to the various workshops to ensure that they were upholding those standards.

Musket and rifle shot prior to standardization had tremendous variability in caliber. This was because barrel width wasn't entirely standardized, and extra windage was expected when loading a smoothbore weapon.

The Lord Admiral was Dan van Vranken. While he had grown up in the countryside, he had a strong work ethic which kept him at the very least on par with the remainder of the government, but as a Dutch naval minister, he was a sore disappointment. The Dutch had hundreds of qualified naval officers, or politicians with more naval backgrounds, but virtually all of them, and certainly the best of them had been members of the Orange Party. He was unable to reduce or keep the Naval budget in check, but his diligence prevented the increase in cost to the navy within acceptable boundaries.

The Lord Admiral was Dan van Vranken. While he had grown up in the countryside, he had a strong work ethic which kept him at the very least on par with the remainder of the government, but as a Dutch naval minister, he was a sore disappointment. The Dutch had hundreds of qualified naval officers, or politicians with more naval backgrounds, but virtually all of them, and certainly the best of them had been members of the Orange Party. He was unable to reduce or keep the Naval budget in check, but his diligence prevented the increase in cost to the navy within acceptable boundaries.

Vranken wasn't a very capable naval administrator, as the best of them were in the Orange party, but his hard work kept costs from spiraling out of control.

The Justice minister was Arjan Courtland, many thinking his name was a pun. For the head of justice and administration of the police across the Empire, Courtland was an astonishingly easy going man. Through that nature however, Courtland was a very intelligent man who was very often more aware of a given situation than he seemed.

The Justice minister was Arjan Courtland, many thinking his name was a pun. For the head of justice and administration of the police across the Empire, Courtland was an astonishingly easy going man. Through that nature however, Courtland was a very intelligent man who was very often more aware of a given situation than he seemed.

Courland had been a moderator, rather than a barrister for much of his career, which gave him a much more convivial personality. This was a major factor in securing his office.

In India, the ruling minister was Josse Vanderbilt. Like many others, he was a firm advocate of industry and in advancing the economic state of India, but he did so with little regard to the safety or well being of the citizens of India. He deemed them to be second class citizens, and attitude which had not been common in previous ministers of India. While India would increase its industrial output by ten percent in the next 5 years, it also came closer to rebellion than any other region in the Dutch Empire.

In India, the ruling minister was Josse Vanderbilt. Like many others, he was a firm advocate of industry and in advancing the economic state of India, but he did so with little regard to the safety or well being of the citizens of India. He deemed them to be second class citizens, and attitude which had not been common in previous ministers of India. While India would increase its industrial output by ten percent in the next 5 years, it also came closer to rebellion than any other region in the Dutch Empire.

Vanderbilt was one of the few nationalists in the Republican party. He viewed the people of India as inherently inferior to the Europeans and the Dutch in particular.

Lastly, the American minister was Daniel Woorbeck, an American born Dutchman from Pennsylvania. He came from a strict Lutheran family, which coloured his opinions on policy and ideology, enforcing one of the most right wing governments in the Empire. Barely capable of speaking any European languages other than heavily accented German, he never did fit in entirely with the rest of the Dutch government, but he was popular with the relatively religiously conservative populace in the Northern portion of America. While Woorbeck would have been catastrophic in Europe, he fit well with North America.

Lastly, the American minister was Daniel Woorbeck, an American born Dutchman from Pennsylvania. He came from a strict Lutheran family, which coloured his opinions on policy and ideology, enforcing one of the most right wing governments in the Empire. Barely capable of speaking any European languages other than heavily accented German, he never did fit in entirely with the rest of the Dutch government, but he was popular with the relatively religiously conservative populace in the Northern portion of America. While Woorbeck would have been catastrophic in Europe, he fit well with North America.

Woorbeck had been a Lutheran minister before being elected governor of Philadelphia. From there, he expanded his base of support in Massachusetts and Albany. Florida, which had been heavily militarized in the 1730s were far more receptive to the Orange party which Karel Vrooman represented.

These ministers were certainly of a more peaceful state of mind, but noting that both the next election as well as the renewal or renegotiation of their ceasefire with the British coming in four years, they would need to strengthen themselves before the unthinkable could happen. Their first act in office was to enact the “50 years act” whereby a party could only run for national office if the officials had collectively held the title of governor, councillor, ambassador, senator or other equivalent office for 50 years. While this did not prevent those smaller political, nobility led parties from existing, it did stop them from diluting the ballots. The Dutch concession to win over those parties, as their support was required to avoid a vote of non-confidence, was to give them formal recognition at a municipal level so long as they could afford a local office, where they could then harass the city’s mayor by officially sitting in on all his meetings.

These ministers were certainly of a more peaceful state of mind, but noting that both the next election as well as the renewal or renegotiation of their ceasefire with the British coming in four years, they would need to strengthen themselves before the unthinkable could happen. Their first act in office was to enact the “50 years act” whereby a party could only run for national office if the officials had collectively held the title of governor, councillor, ambassador, senator or other equivalent office for 50 years. While this did not prevent those smaller political, nobility led parties from existing, it did stop them from diluting the ballots. The Dutch concession to win over those parties, as their support was required to avoid a vote of non-confidence, was to give them formal recognition at a municipal level so long as they could afford a local office, where they could then harass the city’s mayor by officially sitting in on all his meetings. Even so, control was slowly slipping away from the Republicans. Social reform across their empire was coming, but no one knew what it was to be. Europe was changing rapidly, and the world was shrinking, and as those factors moved around the befuddled Dutch, it became impossible for any one political party to maintain the control that a king could have years before.

Even so, control was slowly slipping away from the Republicans. Social reform across their empire was coming, but no one knew what it was to be. Europe was changing rapidly, and the world was shrinking, and as those factors moved around the befuddled Dutch, it became impossible for any one political party to maintain the control that a king could have years before.

The Dutch were aware that the public wanted change, but revolution was headed off by confusion over what change people wanted. People weren't even sure if the change should have been the government. In any event, few wanted a violent revolt after so many years of war.

Next we will be presenting world news followed by Doctor O’Connell discussing meteor sightings. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be presenting world news followed by Doctor O’Connell discussing meteor sightings. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.