Part 49: March 29 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be talking about the production of chocolate, and why Swiss chocolate tastes so good. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the forty ninth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the start of the birth of the Federation that people know of today.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the forty ninth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the start of the birth of the Federation that people know of today. By 1780, the United Provinces had become restless. The Federation was fully formed as something altogether out of direct, perpetual Dutch rule. While the founding fathers of the Federation had been popular enough for their actions in many of the provinces, and recognized as great by the councillors elected from the independent nations of the Federation, not every Dutch minister would find himself in that enviable position. While they were in office, the populace of the United Provinces were largely placated by them and their ability to guarantee continued improvement to Amsterdam and their own bank rolls even as they funded the creation of new political offices in each of their surrounding nations.

By 1780, the United Provinces had become restless. The Federation was fully formed as something altogether out of direct, perpetual Dutch rule. While the founding fathers of the Federation had been popular enough for their actions in many of the provinces, and recognized as great by the councillors elected from the independent nations of the Federation, not every Dutch minister would find himself in that enviable position. While they were in office, the populace of the United Provinces were largely placated by them and their ability to guarantee continued improvement to Amsterdam and their own bank rolls even as they funded the creation of new political offices in each of their surrounding nations.

Even the Reichstag in Berlin was built with Dutch financing. Not a member of the Federation, the Dutch had invested in Prussian infrastructure to help them control the populace and keep them strong against the Polish crusades.

In 1782, six years after the beginning of the election, the council had been fully formed from national leaders from all across the Dutch conquered lands. Accommodating nations that were further East such as India, and their Mediterranean allies, the Western Atlantic Federation was renamed the Atlantic Federation, sensitive mostly to the idea that “western” had come to indicate a specific national type. While Atlantic was no longer appropriate anymore, at the very least, no one would find it relevantly exclusionary.

In 1782, six years after the beginning of the election, the council had been fully formed from national leaders from all across the Dutch conquered lands. Accommodating nations that were further East such as India, and their Mediterranean allies, the Western Atlantic Federation was renamed the Atlantic Federation, sensitive mostly to the idea that “western” had come to indicate a specific national type. While Atlantic was no longer appropriate anymore, at the very least, no one would find it relevantly exclusionary.

The trade ensign of the Western Atlantic Federation was adopted as the Federation symbol and flag.

Abroad, Prussia refused to join the Federation. Under new law, not only would the King of Prussia, Frederick the first have to abdicate the throne, but the region of Dresden would be granted its independence once more, and Prague would be returned to Austria. Unwilling to make those concessions, the Prussians were willing to remain only allies, and no more.

Abroad, Prussia refused to join the Federation. Under new law, not only would the King of Prussia, Frederick the first have to abdicate the throne, but the region of Dresden would be granted its independence once more, and Prague would be returned to Austria. Unwilling to make those concessions, the Prussians were willing to remain only allies, and no more.

Frederick Wilhelm II refused to join the Federation, which would necessitate that he relinquish control over the German states that had been granted to him. This likely led to Prussia's downfall in the 1800s.

The Ottoman Empire was in a similar state. Their own powerful ruler was unwilling to abdicate in favour of a democratic government, fully knowing that under the new Federation laws, the conquered provinces such as Greece and even Istanbul would have to be granted autonomy. The Ottomans wouldn’t officially join the Atlantic Federation for another fifty years under an exception.

The Ottoman Empire was in a similar state. Their own powerful ruler was unwilling to abdicate in favour of a democratic government, fully knowing that under the new Federation laws, the conquered provinces such as Greece and even Istanbul would have to be granted autonomy. The Ottomans wouldn’t officially join the Atlantic Federation for another fifty years under an exception.

The Ottoman Empire managed to defeat revolutionaries across their Empire, and remained a monarchy up until 1897.

These years were a new golden age for Europe, an age of enlightenment, science, wealth and industry. Only in the East of Europe did the state of the world remain in the olden days, based on tradition and personal martial prowess. Chivalry had a revival in the east, just as democracy took hold in the west, and the dividing lines between them grew sharper by the day.

These years were a new golden age for Europe, an age of enlightenment, science, wealth and industry. Only in the East of Europe did the state of the world remain in the olden days, based on tradition and personal martial prowess. Chivalry had a revival in the east, just as democracy took hold in the west, and the dividing lines between them grew sharper by the day.

The Dividing line lane down across Europe would remain the line in the proverbial sand for over a century, and would culminate in the great wars of the 1900s.

Still, their rule would not last forever, and a less forceful, charismatic panel of ministers would find themselves potentially unable to lead the council, meaning the Dutch could find themselves at a disadvantage in future negotiations, and may even find their own interests brushed aside as the members of the council each pushed and pulled to see their own interests put ahead of all others.

Still, their rule would not last forever, and a less forceful, charismatic panel of ministers would find themselves potentially unable to lead the council, meaning the Dutch could find themselves at a disadvantage in future negotiations, and may even find their own interests brushed aside as the members of the council each pushed and pulled to see their own interests put ahead of all others. As a fortunate turn of events for the Federation, those five men were granted a perpetual position within the Federation council. They had no vote, but were given both honour of both the opening and closing arguments of every meeting. Traditionally, the position of council overseer has been for one with superior reasoning and judgement than the typical councillor, and their power, in theory, was through their tremendous capacity to convince others of a sound course of action. Their appointment to the council’s overseers likely saved the Federation, and almost invariably saved their lives.

As a fortunate turn of events for the Federation, those five men were granted a perpetual position within the Federation council. They had no vote, but were given both honour of both the opening and closing arguments of every meeting. Traditionally, the position of council overseer has been for one with superior reasoning and judgement than the typical councillor, and their power, in theory, was through their tremendous capacity to convince others of a sound course of action. Their appointment to the council’s overseers likely saved the Federation, and almost invariably saved their lives.

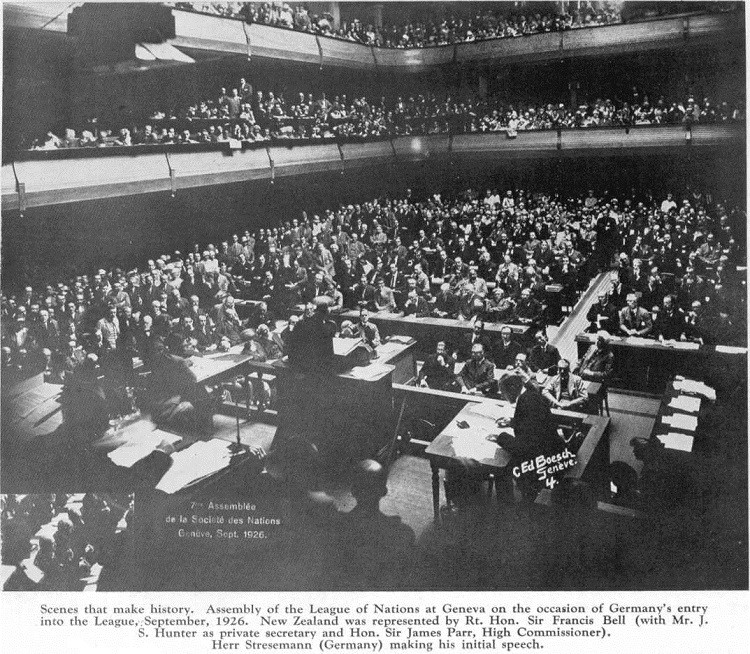

The Federation convenes in Geneva Switzerland, a neutral territory and meeting ground for the Federation. These meetings would continue in Geneva until after the second great war.

This cabinet had only two more years in office before they would turn all of their attention to the administration of the Federation, meaning the Dutch would have another election to determine their own rulers. But as this election came forward, the Orange party, tired of the government continually neglecting the United Provinces in favour of benefiting the Federation, had begun to conspire against them.

This cabinet had only two more years in office before they would turn all of their attention to the administration of the Federation, meaning the Dutch would have another election to determine their own rulers. But as this election came forward, the Orange party, tired of the government continually neglecting the United Provinces in favour of benefiting the Federation, had begun to conspire against them. Prior to the 1700s, the idea of nationalism had been fairly limited. Individuals would take pride from following certain charismatic leaders, or in the city that they could reside in. In the United provinces however, leadership was highly flexible, and the idea that one would have to change their focus of attention every eight years did not fit with the former model. Increasingly, it was the ideals, the accomplishments and the philosophies of the United Provinces that had led to the advent of an ultra nationalist movement. These few believed the Dutch people to be inherently culturally superior, or at the very least, believed that their culture itself was something to take tremendous pride in.

Prior to the 1700s, the idea of nationalism had been fairly limited. Individuals would take pride from following certain charismatic leaders, or in the city that they could reside in. In the United provinces however, leadership was highly flexible, and the idea that one would have to change their focus of attention every eight years did not fit with the former model. Increasingly, it was the ideals, the accomplishments and the philosophies of the United Provinces that had led to the advent of an ultra nationalist movement. These few believed the Dutch people to be inherently culturally superior, or at the very least, believed that their culture itself was something to take tremendous pride in.

Nationalism was often the main focus of propaganda, and every nation relied upon it. While nationalism could be harnessed for great evil, it could also be used to rally a nation towards a just cause.

This was personified most vocally by the Orange party, and an emerging group of royalists among the nobility. The philosophy in general, was that the military rulers of the United Provinces had conquered everything before them, and had marked their superiority, but the weak will of the Republican party had put the plebiscite ahead of the Dutch. Not just the nobility, but the poor and the labourers of the United Provinces as well. They believed that the Dutch people deserved what they had reaped, and that the infirm hearts of the Republicans that were buying the love of France, Spain, Germany, Britain were not a fit reward for the Dutch people.

This was personified most vocally by the Orange party, and an emerging group of royalists among the nobility. The philosophy in general, was that the military rulers of the United Provinces had conquered everything before them, and had marked their superiority, but the weak will of the Republican party had put the plebiscite ahead of the Dutch. Not just the nobility, but the poor and the labourers of the United Provinces as well. They believed that the Dutch people deserved what they had reaped, and that the infirm hearts of the Republicans that were buying the love of France, Spain, Germany, Britain were not a fit reward for the Dutch people.

Vienna is defended from the Polish crusaders who temporarily occupied Hungary. The garrison contained over ten thousand men, and cost over one hundred million guilders per annum to maintain.

Their goal was the “Emancipation of the Dutch people from the tyrannical wants and needs of her own vast Empire.” and they claimed that “The prize for victory at the cost of good Dutch blood and toil has been a great mound of lands, territories and goods, but piled high on our chest, it has done naught but suffocate us.” Their general desire was to abdicate entirely from their position in the Federation, and to let the hundreds of selfish millions that relied on Dutch trade to grow and prosper could rot, pay to defend their own borders, and turn to their own coffers to finance their growth.

Their goal was the “Emancipation of the Dutch people from the tyrannical wants and needs of her own vast Empire.” and they claimed that “The prize for victory at the cost of good Dutch blood and toil has been a great mound of lands, territories and goods, but piled high on our chest, it has done naught but suffocate us.” Their general desire was to abdicate entirely from their position in the Federation, and to let the hundreds of selfish millions that relied on Dutch trade to grow and prosper could rot, pay to defend their own borders, and turn to their own coffers to finance their growth. To a degree, this had become true. While the United Provinces was not the most industrially advanced nation in the world, it was the Dutch stock exchange, banks and trade ports that kept much of the otherwise stagnating business across their vast Empire afloat. Demand had nearly ceased and prices had plummeted, slashing profit to the bone. Many factories could not afford or justify the expense of expanding their facilities, or in purchasing the newest, safest machines. As such, the Dutch government often subsidized them in an attempt to placate the working classes. Farms conversely had run dry, and prices for food were skyrocketing. While Amsterdam itself had no problem feeding its own population, their own prices were heavily influenced by this external need, and it was again the people of Amsterdam who had to finance the tremendous land reclamation efforts that helped feed the Federation.

To a degree, this had become true. While the United Provinces was not the most industrially advanced nation in the world, it was the Dutch stock exchange, banks and trade ports that kept much of the otherwise stagnating business across their vast Empire afloat. Demand had nearly ceased and prices had plummeted, slashing profit to the bone. Many factories could not afford or justify the expense of expanding their facilities, or in purchasing the newest, safest machines. As such, the Dutch government often subsidized them in an attempt to placate the working classes. Farms conversely had run dry, and prices for food were skyrocketing. While Amsterdam itself had no problem feeding its own population, their own prices were heavily influenced by this external need, and it was again the people of Amsterdam who had to finance the tremendous land reclamation efforts that helped feed the Federation.

The Dutch were still the biggest traders of spice by volume, and still kept the largest take for themselves, but whereas before the Dutch had only a few million citizens to sell spice to, the Federation had over three hundred million, and with a near identical supply. The Dutch insured that their sale to foreign nations did not decline, and so the share for domestic markets had plummeted.

All in all, the average man living in Amsterdam had not had his station significantly improve since the 1740s, at which point pay levelled off sharply, as had the amount of investment into the Dutch cities. The Dutch spice trade from India had remained identical in volume since 1730, the average Dutch citizen in 1730 could buy himself five ounces of spice in a month on a worker’s wage, but by 1780. The population had grown far beyond the supply of spices from India, and worse, the Dutch were engaging in price manipulating practices to sell their spices in vast quantities without increasing the price by drawing mass amounts of spice from domestic market. Those same five ounces would be bought in a year or more.

All in all, the average man living in Amsterdam had not had his station significantly improve since the 1740s, at which point pay levelled off sharply, as had the amount of investment into the Dutch cities. The Dutch spice trade from India had remained identical in volume since 1730, the average Dutch citizen in 1730 could buy himself five ounces of spice in a month on a worker’s wage, but by 1780. The population had grown far beyond the supply of spices from India, and worse, the Dutch were engaging in price manipulating practices to sell their spices in vast quantities without increasing the price by drawing mass amounts of spice from domestic market. Those same five ounces would be bought in a year or more. The Orange party was acting behind the scenes, but evidence of their duplicity was well known after the fact. The Orange party was in direct or near direct control of at the very least eighty percent of the Federation’s armed forces, and every living, sane general was loyal to the Orangists rather than to the Republicans. While William the fourth of England was not to lead the Dutch after the revolution, he too was a part of the conspiracy. He had conspired with his cousin that he would remain influential in England, and he and his parliament would take back control of Britain while William the first would take control of the United Provinces. Influence of the two Williams would involve the British attempting to prevent the Federation from a disastrous civil war to reclaim the United Provinces, while William the First would insure the Military of the United Provinces would remain abroad to defend the Eastern European states for ten years before withdrawing in their tens of thousands back to Amsterdam.

The Orange party was acting behind the scenes, but evidence of their duplicity was well known after the fact. The Orange party was in direct or near direct control of at the very least eighty percent of the Federation’s armed forces, and every living, sane general was loyal to the Orangists rather than to the Republicans. While William the fourth of England was not to lead the Dutch after the revolution, he too was a part of the conspiracy. He had conspired with his cousin that he would remain influential in England, and he and his parliament would take back control of Britain while William the first would take control of the United Provinces. Influence of the two Williams would involve the British attempting to prevent the Federation from a disastrous civil war to reclaim the United Provinces, while William the First would insure the Military of the United Provinces would remain abroad to defend the Eastern European states for ten years before withdrawing in their tens of thousands back to Amsterdam.

William the fourth was a divisive figure in history. On one hand, he betrayed the Federation, denying them support from England to retake Amsterdam from the rebels, and heavily influencing the British parliament. On the other, he also spent a great deal of his effort in ensuring the Federation did not falter against an aggressive or opportunistic Poland.

This second guarantee was not one of altruism. The Polish crusaders were still at large, and if eighty percent of the Dutch army was withdrawn from the front immediately, the Dutch would find themselves exposed directly with much of Europe falling immediately to the Polish Empire. The last thing the Dutch wanted was the Polish Empire pushing directly to their border with the crusade still at hand.

This second guarantee was not one of altruism. The Polish crusaders were still at large, and if eighty percent of the Dutch army was withdrawn from the front immediately, the Dutch would find themselves exposed directly with much of Europe falling immediately to the Polish Empire. The last thing the Dutch wanted was the Polish Empire pushing directly to their border with the crusade still at hand.

Prague is pressured in the East, but is reclaimed by Prussian forces. The lines between Prussia and Poland were in constant flux, and with the collapse of Dutch economic aid to Prussia, the Federation could no longer afford to sustain the Prussian army. Their money and men had to be turned to their own forces to hold back the crusaders.

Current day knowledge of the events of the 1700s seems to imply that the Dutch Republican Party were actually aware of the conspiracy brewing around them. The fear for them, was the threat of a direct coup d’etat, as with the entire army a potential threat, up to and especially including the blue guard, the ministers would almost certainly die. In fact, correspondence of the time implied that agents of the Republican party had not tried to directly subvert the revolution, but rather, attempted to encourage a peaceful resolution of the revolution. The Dutch ministers, theoretically leaders of the Federation had negotiated positions in the council before the fall of the United Provinces, but to maintain some power and command some respect, they could not directly abdicate.

Current day knowledge of the events of the 1700s seems to imply that the Dutch Republican Party were actually aware of the conspiracy brewing around them. The fear for them, was the threat of a direct coup d’etat, as with the entire army a potential threat, up to and especially including the blue guard, the ministers would almost certainly die. In fact, correspondence of the time implied that agents of the Republican party had not tried to directly subvert the revolution, but rather, attempted to encourage a peaceful resolution of the revolution. The Dutch ministers, theoretically leaders of the Federation had negotiated positions in the council before the fall of the United Provinces, but to maintain some power and command some respect, they could not directly abdicate.

The Dutch ministers wished to avoid a bloody coup, and so spent much of their time abroad. While this meant the Orange party could effectively move in to capture the government entirely intact, it also meant the takeover would be relatively bloodless.

This cabinet was not the liberating cabinet of 1776, but the weak cabinet of Schouman that followed. In office for only four months before rebellion broke out, Schouman and his cabinet is scarcely remembered in detail, and their ability in office could not have been put to the test. The entirety of the Dutch parliament had been forced to flee to England, then to Paris.

This cabinet was not the liberating cabinet of 1776, but the weak cabinet of Schouman that followed. In office for only four months before rebellion broke out, Schouman and his cabinet is scarcely remembered in detail, and their ability in office could not have been put to the test. The entirety of the Dutch parliament had been forced to flee to England, then to Paris.

Xander Schouman knew he had no hope of controlling the government or his nation. While able to attain an easy majority from across the Empire, the Dutch people, who were the ones who had held all of the cards over the years were the one group to rebel.

The one notable member of the Dutch Republican party was the traitor Albert Grasdyke, who was an Orange sympathiser. It’s still uncertain how he managed to arrive as the Defence Minister, but with so many Orangists as the most qualified for the position, and so few of the Republicans fit for it, it was likely that many defence ministers were Orange sympathisers. It was likely that he was simply approached by the Orange party, or perhaps William the first to join in on the conspiracy after he attained office.

The one notable member of the Dutch Republican party was the traitor Albert Grasdyke, who was an Orange sympathiser. It’s still uncertain how he managed to arrive as the Defence Minister, but with so many Orangists as the most qualified for the position, and so few of the Republicans fit for it, it was likely that many defence ministers were Orange sympathisers. It was likely that he was simply approached by the Orange party, or perhaps William the first to join in on the conspiracy after he attained office.

Albert Grasdyke was considered a hero or a villain depending on who one asked. An old man, he could actually recall what the world was like when the nation was still just the United Provinces, and not the Federation. A time that he was very fond of.

Grasdyke betrayed the Republican Party in several ways. For one, pay meant to go to soldiers was embezzled by the tens of millions, stored under the Hague. This fomented a tremendous amount of hatred to the Republican party from soldiers in the field and abroad, and the Republicans were already unpopular to those men. Second, he made sure to move near all of the regiments suspected of loyalist ties to the far east theater, and recalled all of the battalions most directly loyal to the Orange party back to Western Europe. Schouman being a peacetime Stadtholder was neutered, and even had he wished to mobilize the armies otherwise, he no longer had the authority to do so.

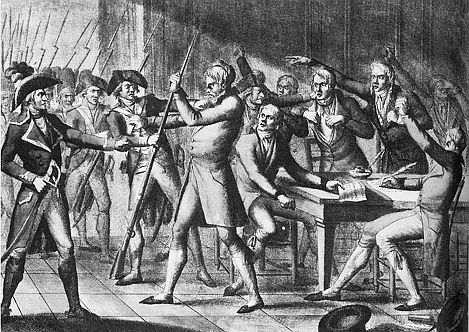

Grasdyke betrayed the Republican Party in several ways. For one, pay meant to go to soldiers was embezzled by the tens of millions, stored under the Hague. This fomented a tremendous amount of hatred to the Republican party from soldiers in the field and abroad, and the Republicans were already unpopular to those men. Second, he made sure to move near all of the regiments suspected of loyalist ties to the far east theater, and recalled all of the battalions most directly loyal to the Orange party back to Western Europe. Schouman being a peacetime Stadtholder was neutered, and even had he wished to mobilize the armies otherwise, he no longer had the authority to do so. Instead, in 1786, a mere four months after the election, the Orange party led their revolt. The fortresses around Amsterdam had already been secured by the Orange party from within, and all of the armies the United Provinces were loyal to the Orange revolution. Some of the best of the Dutch army would be assailing a parliament guarded by traitors. It was only by luck that their cabinet had managed to flee to England a week prior under the pretense of business.

Instead, in 1786, a mere four months after the election, the Orange party led their revolt. The fortresses around Amsterdam had already been secured by the Orange party from within, and all of the armies the United Provinces were loyal to the Orange revolution. Some of the best of the Dutch army would be assailing a parliament guarded by traitors. It was only by luck that their cabinet had managed to flee to England a week prior under the pretense of business.

The Dutch maneuver an army to block the Hannoverian members of the Federation from ruining the revolution. Meanwhile, two revolutionary armies prepare to officially take over Amsterdam and the Hague.

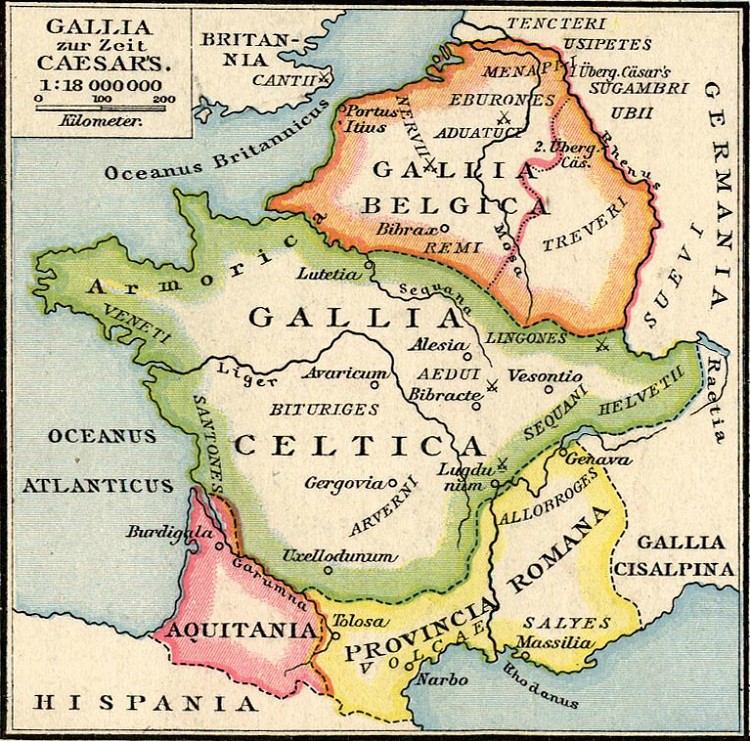

This would lead to the last battle the United Provinces would fight, and would mark their exit from the eighty years war. The final battle would not be a climax, they would not be destroyed in a bang, but with a whimper. Five hundred Dutch men, farmers, factory workers and the poor stepped forward to the defence of the Republic. Arrayed against them, the entire army of the Dutch Empire flying a new banner. One of the kingdom of Gallia, the official name of the Netherlands. Taking their name from the Roman term for their lands of Gallia Belgae, they hoped to invoke the notion of a fierce, martial land.

This would lead to the last battle the United Provinces would fight, and would mark their exit from the eighty years war. The final battle would not be a climax, they would not be destroyed in a bang, but with a whimper. Five hundred Dutch men, farmers, factory workers and the poor stepped forward to the defence of the Republic. Arrayed against them, the entire army of the Dutch Empire flying a new banner. One of the kingdom of Gallia, the official name of the Netherlands. Taking their name from the Roman term for their lands of Gallia Belgae, they hoped to invoke the notion of a fierce, martial land.

Gallia Belgia, from which Belgium takes its name was named by the Romans for the Gauls that inhabited that land, and the ferocious bellows they would make in battle, like a great beast of war. Believing the roman name for their lands more suitable for a powerful, civilized monarchy, the Dutch named their nation Gallia, but were commonly known as the Netherlands. The Netherlands meaning "the low lands" was not considered adequately regal, and the United Provinces not being indicative of a single kingdom, the monarchy preferred the Latin term.

Next, we will be talking Swiss chocolate, followed by world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next, we will be talking Swiss chocolate, followed by world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.