Part 5: Opiate of the Masses

Chapter 5: Opiate of the Masses

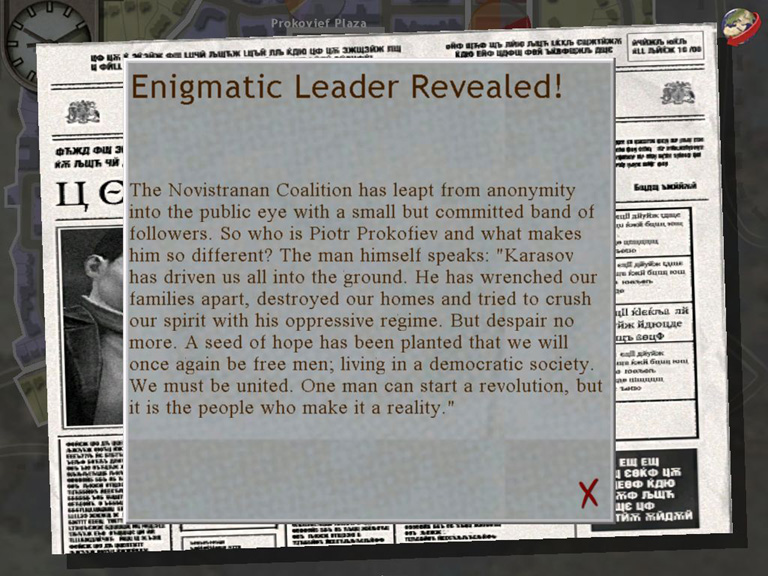

The days following Karasov's Presidential Declaration were busy ones for the Novistranan Coalition. Prokofiev attempted to hire a priest by the name of Oleg Baturin to his side, and while the local Ekaterine cleric joined him, the details on his condition to join the Coalition are still being worked out.

Shortly after Baturin joined alongside Prokofiev and Nasarov, the Novistranan Coalition really began to take off with the working-class population of Ekaterine. The rate at which they gathered support ignited the jealousy and enmity of the other factions, but the network of informants that Prokofiev had set up in the early days of his movement helped keep tabs on who was doing what. This would become very useful when it became clear that the other factions were attacking Coalition support using underhanded tactics.

* * *

Piotr Prokofiev's Diary - Thirteenth Entry: 21/02/1996

Marx wrote that religion was the opiate of the masses. Many believed that he simply meant religion was a disease, a way for societies to bog themselves down in morality and ethics, paving the way to oppression and disaster. However, I believe Marx meant that religion was not the disease of society, but merely a symptom. The true disease is the oppression of the working class, and religion is a way for the oppressors to keep the proletariat in line. Although, why should I deny the people that which comforts them? Much like a patient that takes drugs to alleviate their pain, so must the oppressed cling to a drug of their own to survive. I am not one to judge. If the people can be won with the love of God, then I will accommodate them.

After my talk with Nasarov, it seems increasingly clear to me that the middle-class, those men and women complicit in the elite's schemes and carrying the disease of the bourgeoisie, are necessary to my struggle. They may be oppressors without their knowing, but I can enlighten them to the error of their ways if I can get the proper spokesperson to carry my message.

Oleg Baturin, a local cleric in Prokovief Plaza, seems to be my best bet. I could risk getting into contact with Friar Karamozovv, but he's on the Church of Novistrana's payroll. I am already having enough trouble managing the Union of Socialist Workers, misguided as they are, as it is. I don't need the church to step up and cause further trouble, but if my encounter with Baturin fails, I'll get in touch with the good friar.

* * *

"Do you believe in God, Mr. Prokofiev?"

"I fail to see how this is relevant to our discussion," Prokofiev replied, unsure of the priest's intentions. Father Baturin, a thin, bald, and aging Novistranan, gave a small but sincere smile. Despite his frail physique for a man his age, the priest had a kind face and calmness of mind that gave him an aura of peace. It certainly helped keep his flock in order, as Prokofiev witnessed before inviting the man over for lunch at the Bar Solmaz, a quiet hideaway in Prokovief Plaza.

"It's not relevant to your movement, I agree," the priest said, then paused to sip from his wine. "I want to know what you believe, not what you say your faction believes."

"Father, I thought the idea of God was something only clerics like yourself needed to worry with," Prokofiev said, crossing his arms and frowning. "My faction is a coalition, not a one-man movement."

"Yes, yes, you made that quite clear earlier in our conversation," Baturin nodded, putting his glass back down on the restaurant table. He closed his eyes and rested his head on the tips of his fingers, his hands mimicking a Catholic prayer. "But if you want me to give you an answer regarding your offer to join the Novistranan Coalition, I need your answer in return."

Prokofiev sighed. He had been sitting and debating the needs of the people and attempting to hire the cleric before him for close to two hours. While he allowed Baturin some leeway on guiding the conversation, they hadn't touched on the subject of personal belief. Until now, anyway.

"Father, we have had quite a good talk up until this point, and we have even debated over the terms of your contract should you wish to join us. Are you still hesitant about joining me?"

"Far from it, I've made my decision quite a while ago," Baturin replied teasingly, a twinkle in his eye. "All I want to know is what you believe. Is it so hard for us to have one final topic of discussion?"

"No, it's not," Prokofiev shook his head. "I just don't want to have to waste your time preaching to me when you could be helping our comrades."

"This isn't about my preaching. I just want to know. Go on," Baturin pushed. "Humor me."

"Very well," Prokofiev shrugged. "I do not know what to believe in, Father. When I was young, I learned that organized religion was just another stone for the proletariat to carry. I never did enjoy it. I never enjoyed the idea of praising something that I couldn't see, or following something that could judge me just for being who I was."

He waited for Baturin to speak, but when the priest remained silent, Prokofiev continued. "Hell, I was anti-religion and an atheist for as long as I can remember thinking, 'Does God exist?' I thought that if an all-powerful being did exist, He would not have made us suffer each other's pain and hatred.

"Ever since I have witnessed the rise of Karasov and seen people turn to fighting him, I thought that the people's will was enough to carry their hatred, their desire for a better world. When I spoke to so many of them, though, they would admit that they were devout Catholics. They said they got their strength from God. I thought it was just a way for them to cope, but..."

"Yes?" Baturin prompted when Prokofiev stopped, thinking.

"Well, maybe they are on to something. I haven't gotten the time to research the spirit, only how society uses the idea of spirituality to control us. Maybe we do have something more within us. Something waiting to be released by someone greater than us."

"So, you are an agnostic?"

"I wouldn't put it that way, Father," Prokofiev replied, rubbing his chin and absentmindedly stirring the wine inside his glass before sipping from it. "Maybe this 'something' can be triggered by words, by a person who can speak to their heart. Maybe it can triggered by a man of vision instead of the Bible."

"An atheist, then," Baturin concluded, lowering his hands back to the table.

"I guess I've never changed, Father," Prokofiev said by way of apology. "My concerns are for the people, not with my own soul. If God exists, He can forgive me for worrying about the plight of the living rather than the mysteries of the dead."

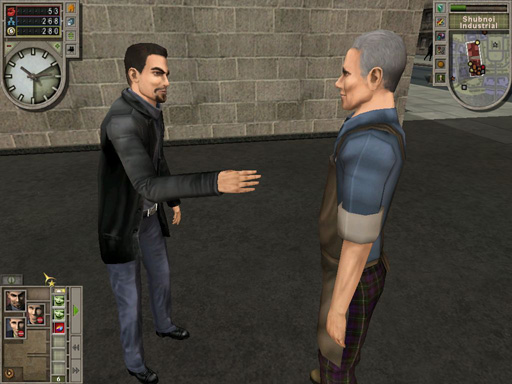

The two men sat looking at each other in silence. Prokofiev reached below the desk and drew out a fresh copy of the headhunting contract he had used with Josef Nasarov. This one was quite different in the terms of agreement, offering Baturin a number of resources to help with his local neighborhood's poor citizenry.

"I hope the fact I'm a non-believer won't cause you to reject my offer outright," Prokofiev said, sliding the contract forward. "The Novistranan Coalition could use someone like you to speak to the hearts of the faithful."

"Too many people are worried about their own salvation and self-profit, my son," Baturin replied, ignoring the contract and staring into Prokofiev's eyes. "I do not blame them. We must do all we can to make sure we survive these days. I try to bring a sense of comfort to those who are in pain, but many times I end up donating to men and women who quickly turn to crime and organized groups who try to cause further conflict."

Even though Baturin wasn't mentioning names, Prokofiev knew he was speaking about the unions and other such institutions. He bit his tongue and let the priest continue.

"Still, those are the problems of our time, and I cannot convince them to wait for salvation. Rather, they must seize it for themselves, all the while trusting their soul to the Lord and coming to us for guidance. I do not care if you are a non-believer, Mr. Prokofiev," Baturin pointed at Prokofiev's chest. "I only care that you're trying to do the right thing. Your ideology of helping those less fortunate, while I find it highly aggressive in nature, is something that I can support in these times."

Baturin took the pen lying on the table and signed the contract while Prokofiev stared, his mouth slightly open in surprise. "I hope I can be of service to the Novistranan Coalition," Baturin bowed slightly with his hands clasped together. He was smiling warmly.

The two men got up and shook hands. I'll be damned, Prokofiev thought as he put the contract into a manila folder. This old man is good.

* * *

Piotr Prokofiev's Diary - Fourteenth Entry: 21/02/1996

Oleg Baturin turned out to be a much wilier man than I gave him credit for. While he is no follower of Marx or believer in the oppression of the proletariat, he agreed that oppression in Novistrana would no longer be tolerated.

The priest revealed to me on our way back to the headquarters that he had a small network of charities he kept in close contact with, and that he would be able to pull some strings to help one of our inner circle back on his feet if they began to waver. Despite his evangelical nature, he told me that what people liked to hear most from him were grim revelations of wrongdoing, fire and brimstone-like sermons demonizing oppressors like Karasov and factions that tried to play dirty. These sermons will come in handy to destroy support for other factions.

As a matter of fact, I have already asked Baturin to focus his efforts on the Kutuzov Works and target the Union of Socialist Workers for trying to play at union politics with us. I gave him the important information and sent him on his way. Josef seemed to be uncomfortable that he didn't get to voice his opinion on hiring the priest, but became even more perturbed when I told him the plan to eventually attack the Socialist Workers party. He told me that we should not be attacking a faction of fellow unionizers that promised a worker's paradise like our own, and that we should instead work together to mutual benefit.

I didn't tell him that I had evidence the Socialist Workers had been vandalizing businesses that supported us in Prokovief Plaza and Lissitzki Towers. I'm not sure he would have believed me at the time, anyway, since I didn't have the physical proof yet. Instead I tried to reason with him, but he wouldn't listen to my advice. He left greatly upset, warning me that he wouldn't put up with being enemies with his fellow workers. I shall have to remedy this, and I think I know just how to do it. Too bad that it's going to involve sending Baturin to stir the pot...

* * *

"Josef, I'm glad you could make it," Prokofiev nodded to his friend. He took the last drag of his cigarette, tossed it to the ground, and ground it under his black shoe. "We need to talk."

"Yes, yes we do," Nasarov growled, staring daggers at his friend and pointing at him accusingly. "You promised me that you wouldn't make our third man undermine the workers."

"That's true, and he did no such thing," Prokofiev frowned back, not liking how Nasarov was trying to close space between them. Maybe he shouldn't have picked an alleyway to confront his friend?

"What's this I hear about the Kutuzov Works abandoning nearly all of their support for the Union of Socialist Workers?" Nasarov wasted no time in getting to the point, leaning forward with fists clenched at his sides. "They say they did it because a priest who called himself a voice of the Novistranan Coalition told them that the Union worked a campaign of violence."

"So what?" Prokofiev shot back, quickly losing patience. "You know as well as I do that the vandalism ramping up in areas we control isn't just coincidence. And it's vandalism that wasn't happening until we started getting more support in the industries."

"That could be anyone! You're sending that priest in there without any proof! That's not the way we work!" Nasarov shouted, drawing attention from passerby outside of the alley.

"Then what is the way we work?" replied Prokofiev coolly, ignoring the eyes they were drawing. "What's your big plan for our movement?"

"It's not attacking our comrades in the unions!" Nasarov stabbed his finger in Prokofiev's chest, just short of touching the man himself. "We do not backstab each other!"

"No, we don't," hissed Prokofiev, "but we are the ones promising revolution outside this town, not them. Josef, I signed you up here with me because you are a man that can see past the lies. Don't try to deny that there is inter-union fighting!"

"I'm not going to be a part of it," Nasarov stated with a sense of finality. "If you're going to drag my name and my union into the muck to fight my co-workers, then count me out of this movement."

"Don't talk like that," Prokofiev lowered his voice threateningly. "You know as well as I do that if we can't get cohesive support behind our banner, we will never overthrow Karasov and free our comrades."

"Karasov? I don't give a shit about him right now when it's you who is directly antagonizing the unions!" the aged worker threw his arms up in the air, exasperated. "Why bother using muscle when we're just going to smash each other around with it?"

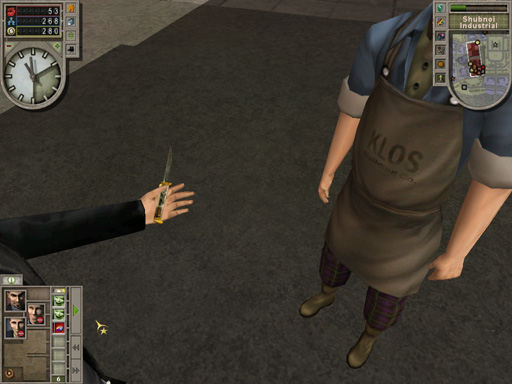

"Because sometimes you need to force someone to face the truth before they're ready," Prokofiev said. He drew out two sharp-looking knives from his pocket. The knives' metal handles were gilded and looked quite ornate.

"What are you doing with those?" Nasarov said quickly, staring at the knives Prokofiev casually clutched on his left hand. Prokofiev handed him one of the blades as an answer, and Nasarov blanched. "What the hell is this about?"

"This is about solidarity, comrade," Prokofiev replied with great intensity. "I want you to answer me honestly. Even knowing that I have sent one of our own to attack your unions, are you still my second? Are you still a comrade, still my friend?"

"What... What's gotten into you?" asked the activist, first staring at the knife then at the visionary in front of him. "What kind of question is that to make with a God-damned knife in your hand?"

"Just answer me!" Prokofiev said, raising the hand with the knife slightly. He then lowered his voice and the knife. "Please."

"I..." Nasarov began, confused, but then straightened his back. "You've been a friend of mine since I've met you, Prokofiev. Even when you were still a kid and I was already getting into the factories to help my family, I always considered you as a true comrade."

"Enough to see your 'true comrade' challenge the very thing you have dedicated yourself to?" Prokofiev asked, no, demanded of him.

"...You... Yes. Yes, you are a true friend, Prokofiev," Nasarov said after a few moments. "You always were loyal."

"Loyal enough for you to consider me as a brother?"

"Yes," Nasarov replied without hesitation. "I loved you like a brother. I still do."

"Then let us make a symbol of it," Prokofiev stated, motioning with the knife. "I want you to make a cut on your right hand."

Oh, you bastard, Nasarov thought, shaking his head even as a smile grew on his face. You vicious little bastard.

"Just draw the blade horizontally across your palm, like so," Prokofiev mimed the motion, pretending to cut his right palm with the knife on his left hand. "It will only hurt for a moment."

"But... why?" Nasarov asked, the smile still on his face, but testing his friend to see if it really was what Prokofiev meant.

"We will become blood brothers, Josef," Prokofiev replied, his face unreadable. "If you do not wish to make this gesture for me, then simply walk away. I will not be upset with you. I will continue the movement by myself, and you will continue getting the assistance I promised you when you signed that contract."

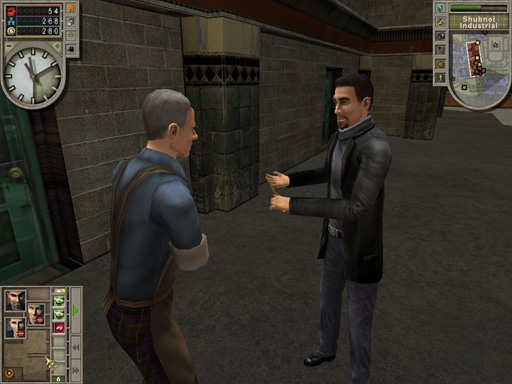

"So what will it be?" Prokofiev asked after the two looked each other over for a few silent moments. The knife rested lightly against his palm. "Are you going to open your eyes, or walk away from it all?"

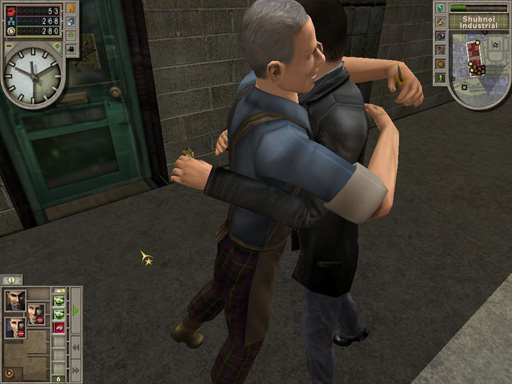

Nasarov didn't speak. Instead, he drew the knife across his right palm as Prokofiev instructed. The pain was sudden and made him snap his arm away in a quick jab of agony, but he quickly regained composure. Prokofiev then cut his own hand, remaining perfectly still as he made a swift slash with the blade.

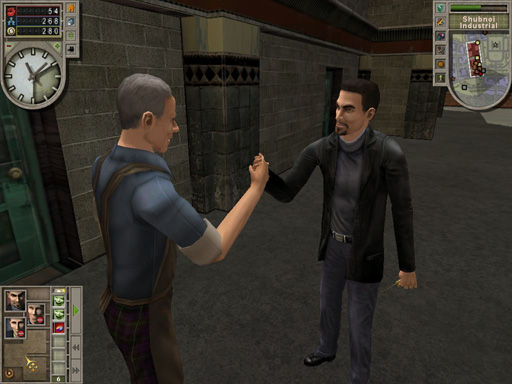

Without speaking, the two clasped their cut hands together, letting the blood mingle between their palms. They then embraced each other in a strong hug.

"You remembered it all without my help," Prokofiev said to his friend, happiness evident in his face. "I'm proud of you, Josef."

"It took me a moment to remember," Nasarov admitted. "It's been so long since we did this, and I didn't recognize the knives right away."

The ritual the two had performed was perfected when the two men were but teenagers. The knives were a pair of heirlooms from the era of Cossacks, and had been in Prokofiev's family as long as they had been made. After the imprisonment of Prokofiev's parents, the four friends Prokofiev, Nasarov, Titov, and Filatov had performed the blood ritual to mark themselves as loyal brothers, even if they never saw each other again. Prokofiev, it seemed, was the only one who still remembered the meaning of the faint scar on their right hands. He was the only one with a real reason to.

"I will continue in the Coalition, comrade," Nasarov nodded once, handing his knife back to Prokofiev.

"Then you need to see these," Prokofiev replied, drawing a series of photographs from his left pocket as he put the knives away in his black jacket. "Those are from the Socialist Workers."

"You... You weren't lying," Nasarov said deflated, examining the photos. "Why didn't you show me these before?"

"Because I wanted to make sure you would still stand tall with me when all you have is my word," Prokofiev said.

"I see," Nasarov said softly, looking down at the ground to mask his momentary shame. He raised his head after a moment, his face all business. "All right. What do you want me to do?"

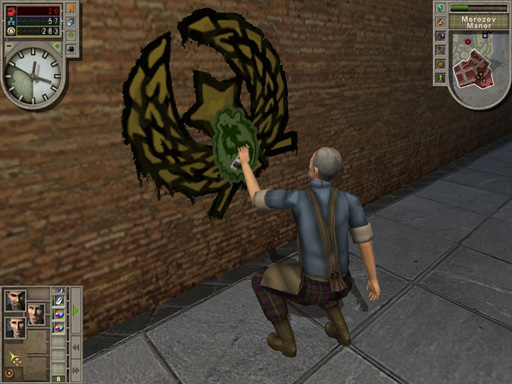

"Buy a can of spray paint," Prokofiev replied as they walked out of the alley. "I want you to speak in the language of our people with a little old-fashioned propaganda. Let them know who is responsible for the recent crime wave."

...

You can count on me, comrade, Nasarov thought after he completed the fifth anti-capitalist tag of the night, running off before he was caught. As he ran he glanced at the fresh cut on his right hand, deep in thought.

* * *

"Caught the attention of the Church of Novistrana, huh?" Josef Nasarov asked Oleg Baturin as they ate lunch in the Coalition's apartment headquarters the following day.

"I was approached by Bishop Baranov, actually," Baturin replied as he sipped his coffee with care.

"Bishop Baranov?" asked Nasarov, messily eating his soup.

"Baranov's not a man to be crossed," warned the priest. "He may speak lightly, but he is a true believer."

"Fine by me," Nasarov shrugged, slurping the remainder of his soup noisily. "Don't see anything wrong with a fellow praying man."

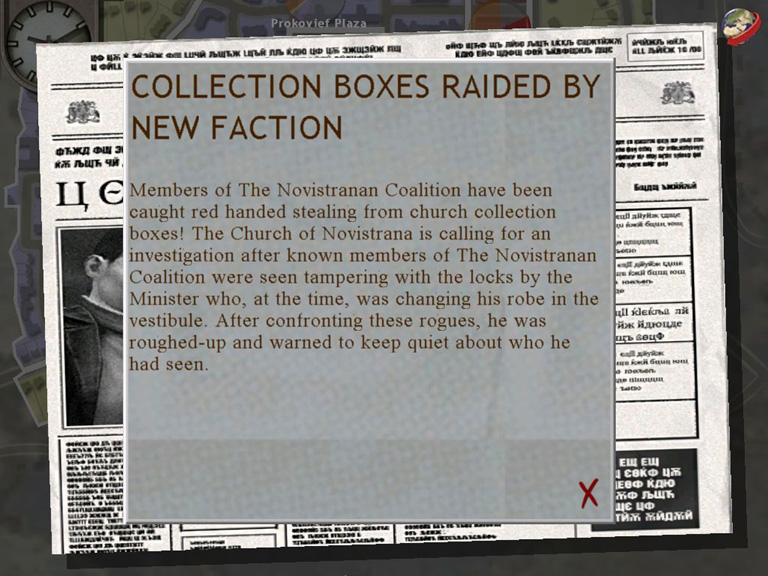

"Well, he's seen something wrong with us, apparently," Prokofiev interrupted as he walked inside the dining area. Carrying two newspapers, he threw the afternoon edition of the Ekaterine Echo on the table. "He's got someone on the inside writing about our activities, a man called Moriz Kalmakov."

"Is this your work, Josef?" Baturin asked after they skimmed the article, raising an eyebrow.

"Father, I haven't gone near Lissitzki Towers," Nasarov growled. "I've been busy with my canvassing and graffiti. Do not accuse me of stealing from the Church ever again."

"I apologize, my son. That was rash of me," bowed the priest before turning to face Prokofiev with the same raised eyebrow.

"I've been at my rallies. Both of them successes, I might add. This Kalmakov is writing sheer lies, and nobody is calling him out on it," Prokofiev asserted, giving Nasarov the morning's edition of the paper. "But here are some good news! Thanks to you two, we're finally on the political map. I made sure that the Echo got an interview from me after the second rally."

"Is this why the Church is targeting us?" asked Nasarov. "Because we're encroaching on their space?"

"Well, we want the faithful to support us," Baturin pointed out. "We need the flock to follow us instead of them."

"The middle-class is willing to support the Church's platform because they have a clean image. We need to strike back at Moriz specifically, get him to stop printing those false columns," Prokofiev explained as he took a seat at the table. "But before that, I want to discuss something much more important. I have the next step of our movement in mind."

The two other men leaned forward at the table, ready to conspire.

* * *

Novistranan Coalition Dossier - Abram Baranov: Faction Leader (The Church of Novistrana)

Baranov is the Bishop of Ekaterine Church. He is a supporter of the Church of Novistrana, a small but growing sect concerned with high morals and family values. Baranov has brought this campaign to the town of Ekaterine with the intention of cleaning up corruption.

* * *

To finish off today's long update, I will be talking about Sleaze.

Sleaze is the dirty reputation of certain actions. Nobody likes a punk smashing up a shop in the name of another faction, and nobody likes having to answer the door only to get an overeager volunteer trying to poll you about your political beliefs. When a faction runs an action that is sleazy and dirty, other factions can jump on it and use the bad fact to boost the effectiveness of their own action, so long as they have enough knowledge that a sleazy action took place in that district.

For example, let's say that an enemy faction is vandalizing property loyal to you in a district. If you have knowledge of the action, you can then run an action to point out the dirty tricks your opposition is relying on. Only certain actions can take advantage of Sleaze, like Canvass, Graffiti, or Revelation. The fun part is that the sleazy action doesn't need to be targeted at you. You can use the trace of other inter-faction fights to boost your own worth or attack a particular faction.

This is where the interface of the game sucks, though. You can't access the sleazy action from the strategy screen. You need to click the little dot that represents an enemy action to zoom in to ground level and look for that spinning icon. Then, you need to click on the icon and click yet another button in order to launch an action from there. Why you can't do it from the strategy screen is beyond me.

Basically, sleaze is bad when you do it, good when others do it. After running a really sleazy action, you may want to consider running some misinformation in that district so your opponents don't get wind of it.