Back to Index

About the Yakuza

Forums poster Arthur D Wolfe was kind enough to share many informative posts and fun facts about the real-life Yakuza to compliment the LP and to give better understanding to it. I've done my best to collect that information here.

An Introduction to the Yakuza

When talking about yakuza, it is important to understand that they are an integral part of Japanese culture. Unlike most criminal organisations that struggle to hide in the dark, the yakuza are fairly open about their existence and their business. Where else in the world can you find a Mafia that has offices open to the public, complete with signs out front? The unique symbiosis between the yakuza, the people and the state extends to the point where it could be said that they form the triangle of society; remove one corner, and it collapses.

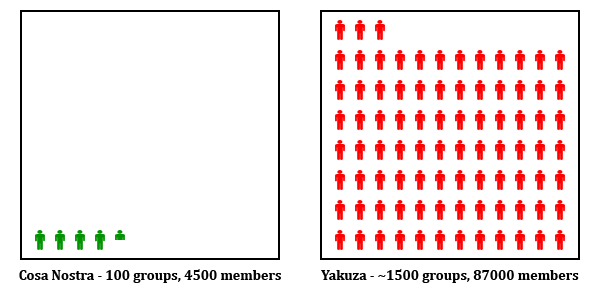

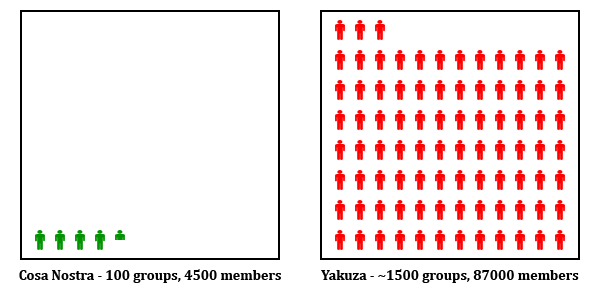

The above statement may sound somewhat absurd to those living in the west, who are used to a system that is harsh on organised crime. For it to make sense, it is important that we put things into a bit of perspective. The organisation that most closely resembles the yakuza is the original Mafia, the Cosa Nostra. With most of its holdings in the Mediterranean and United States, the Cosa Nostra are regarded as one of the biggest and most dangerous criminal organisations in the west. So, how do they compare to the yakuza?

The Cosa Nostra have 4,500 active members worldwide. The yakuza have roughly 87,000 – in Japan alone. For those interested in geography, this is a nation slightly smaller than the state of California and with a population less than half that of the United States. Let this sink in for a moment. Then realise that these are active members, which does not count the numerous thugs and henchmen that follow the orders of local bosses. The yakuza form the biggest criminal entity on Earth, yet reside in a nation with one of the lowest violent crime rates in the first world – an almost absurd combination.

What has allowed the yakuza to grow to such great numbers in a subdued society? How far does their influence extend? Where did they come from, and how did they get where they are? My intention is to answer all these questions and more.

The Origins of the Yakuza

While scholars have not reached full agreement in the subject, the most common heritage ascribed to the yakuza is one that begins in the late sixteenth century with the kabukimono, boisterous ronin and vagabonds that walked the streets in flamboyant dress and used vulgar speech to set themselves apart from the common folk. They referred to themselves as hatamoto-yakko, men of the shogun, but they had no such relation – they were little more than gangs formed by those samurai and soldiers left behind by a society on its way to stability and peace.

The kabukimono were wild and lawless, causing trouble wherever they gathered. Their crimes ranged from simple dine and dash to cutting down civilians for amusement; they would also riot or vandalize public property to alleviate boredom. Despite this chaotic behaviour they were loyal to one another; some even swore to protect their fellow gang members from friends and family should it become necessary. Their antics and relationships became one of the primary inspirations of kabuki theatre, an art form that is still regarded as one of Japan's national arts.

What a kabukimono may have looked like.

The kabukimono faded away over time as the shogunate government became more organised and regular police forces could be established. The shogunate was aided in their efforts by the machi-yakko, civilian police forces formed by volunteers. The modern yakuza claim their heritage begins here, with these “servants of the people” and not the violent kabukimono. Certainly, the machi-yakko were much closer to the chivalric ideal of the yakuza, working to protect and safeguard the people, but there is little historical evidence to link the two.

The modern yakuza appears in the latter half of the seventeenth century in the form of bakuto, gamblers, and tekiya, peddlers. The former were closely knit groups that gave birth to the modern version of the oyabun-kobun (father role – child role) relationship that is the base of yakuza society today. They provided the people with less legal services such as gambling, protection and prostitution – an acceptable arrangement for the government, who preferred such things kept orderly in the hands of a competent organisation. The tekiya peddled illegal goods and controlled the black market, travelling alone or in small groups all over Japan. They also became proficient information brokers, and some found careers as spies for the shogunate.

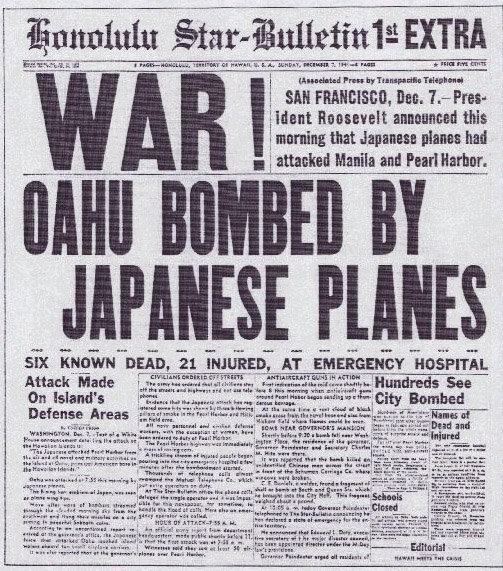

With time the bakuto and tekiya took control of the Japanese underworld, and on the eve of the twentieth century their organisations were close to those of the modern yakuza groups. However, they were still regarded as criminals, and the police had run out of patience with them; efforts had been made by the government to suppress them, and their growth had stagnated. But fate was on their side. Due to certain events beginning in 1941, the yakuza would undergo an amazing rebirth...

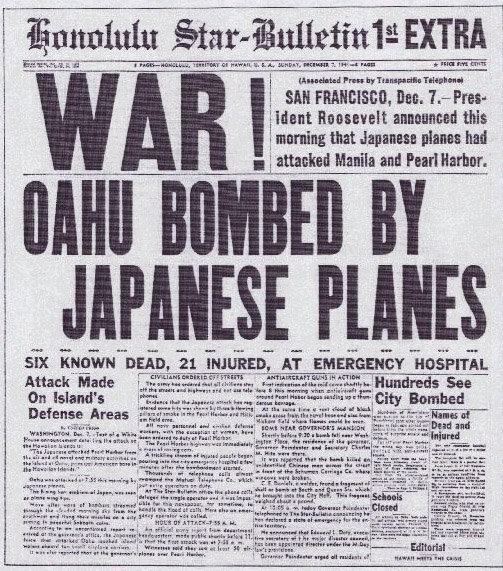

"December 7th, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy" - Franklin D. Roosevelt

The Modern Yakuza Emerge

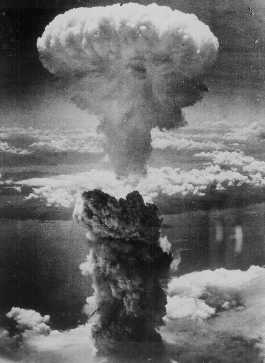

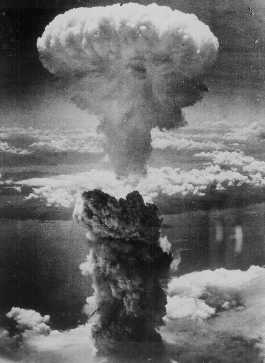

The first of only two nuclear weapons deployed against fellow men...

The second world war ends in a complete victory for the Allies, with Japan being little more than a burnt out husk housing a starving people. Old Tokyo has been burnt to the ground by systematic fire bombing, medical supplies are worth their weight in gold and the people look to the emperor for guidance... They receive none.

The United States install an occupational government and move thousands of troops onto Japanese soil to keep order. Relief efforts, however, are slow coming - the majority of support is going to Europe, and Japan put second. In this country of martial law, chaos and lucrative business opportunities, the yakuza begin their rise to prominence.

A black market of unparalleled size is opened by the tekiya, funnelling military supplies from both armies to the people. Gigantic stores of amphetamines, used as combat drugs during the war, keep minds off the hunger. The occupational government, unable to cope with the crime waves, turn a blind eye to the yakuza as they begin their clean up and take complete control of the underworld. Indeed, some less ethical army representatives do business with the yakuza who provide prostitution, alcohol and drugs for the American soldiers - a business deal that would extend to US soil before long, and last for decades.

A third yakuza archetype, the gurentai, or violent groups, materialises during the post-war years. They are openly violent thugs that sell their services to the highest bidder, cracking down on socialist ideas and unions on order from the occupational government and right-wing politicians. They intermingle with the bakuto and tekiya, and the gangs grow explosively; the modern yakuza groups are born, and begin to spread out over Japan.

By the early sixties, legendary bosses like Yoshio Kodama have earned billions of dollars on drugs, prostitution, speedboat racing and construction kickback schemes. The new Japanese government, having been built alongside these criminal organisations, are forced to rely on them to solve matters with methods not available to the police.

Yakuza often wear black suits, normally reserved for funerals in Japan.

By 1970, the yakuza have complete control over every racket in Japan. Reported crime is at an all-time low; after all, no one is stupid enough to try to steal a piece of the cake when there are tens of thousands of armed gangsters sitting around it. An understanding has been reached between the zaibatsu (giant industrial corporations), the government and the yakuza. Money flows in all directions, and the trinity is complete. People, government and organised crime all rely on one another to function.

The economical boom of the '80s make the yakuza richer than ever, and they enjoy a second golden age. This is also the time they seriously begin excursions abroad, setting up operations in Russia, Europe and the United States. American companies make hesitant contact with these new players, and the FBI starts striking deals. The future seems bright... but dark clouds are forming just beyond the horizon.

The Yakuza Hierarchy

Much like the rest of Japanese society, the yakuza have a strong emphasis on loyalty and the importance of seniority. All members of the organisation are expected to obey their seniors without question, sacrificing themselves without hesitation should the need arise. Yakuza culture states that all followers are teppodama (lit. "rifle ball"), bullets to be fired by their boss. The bullet does not think for itself; it is simply aimed and released.

To foster this kind of blind loyalty, it was necessary for the yakuza to implement a system of reliance. This resulted in the oyabon-kobun relationship (roughly father role - child role), popular among the bakuto already during the seventeenth century. In such a relationship, the oyabun "adopts" kobun, offering them protection, advice and work in exchange for servitude. This may sound strange to a westerner, but in Japan such family loyalty is natural; a father is simply meant to be obeyed.

The adoption ceremony is known as sakazuki-goto (sakazuki being a small sake cup), and consists of the participants taking turns drinking from the same cup in what is originally a Shinto ritual. The kobun keeps the cup after the ceremony, both as a memento and a physical contract - it has to be returned or destroyed in case of an expulsion. The kobun may later hold sakazuki-goto ceremonies of his own and thus adopt kobun of his own. Through this method the family will grow and branch off, to the point where a new family may be formed.

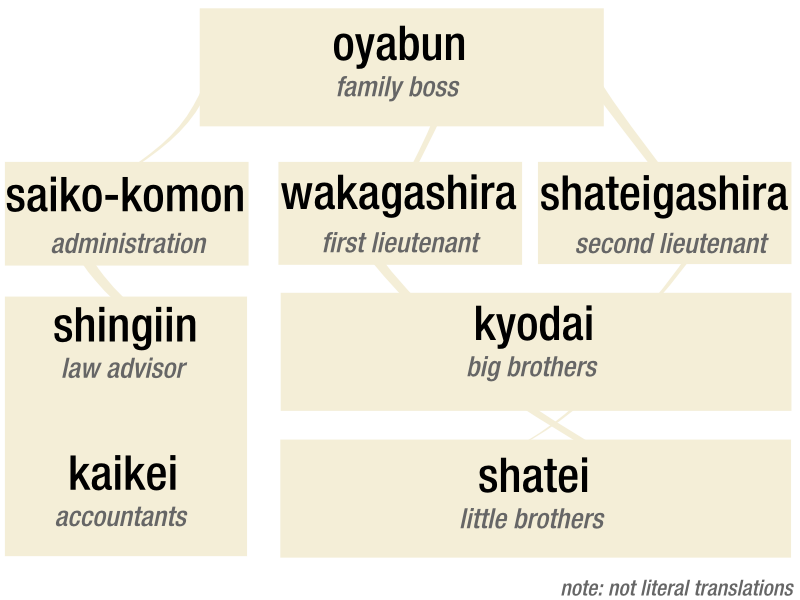

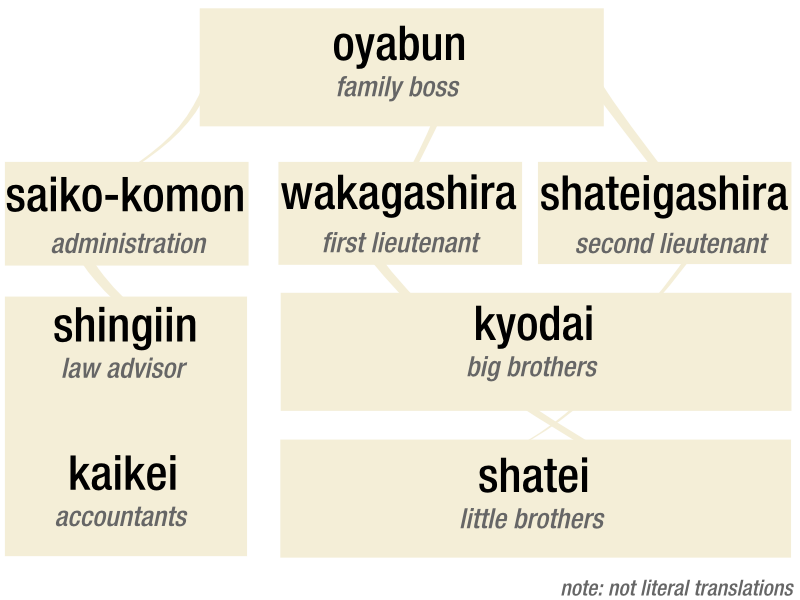

Yakuza family hierarchy, courtesy of Wikipedia.

The oyabun appoints lieutenants and advisers among his kobun and also selects external advisers that are not officially part of the organisation, such as lawyers and press contacts. Thus the family is complete, with all important roles filled and everyone knowing their place. As a yakuza group grows, however, it becomes more difficult to keep a clear organisational layout. Groups like the Yamaguchi-gumi, with literally hundreds of affiliate families, need a more bureaucratic system.

Larger yakuza groups are constructed similarly to corporations. At the top is the group boss, referred to as kumicho (family boss), a rank that implies absolute authority. In descending order, the ranks below the kumicho are saiko-kanbu (executive officers), kanbu (officers), kumi-in (soldiers) and jun-kosei-in (trainees). Within this new hierarchy, families may exist on different levels; family heads are ranked by proximity to the kumicho, which means that a oyabun that is kobun of the kumicho will almost always outrank one who is not.

While the organisation appears complicated to an outsider, those within the group generally only need to keep track of who is immediately above and immediately below. More complicated relations are generally settled on seniority within the group or by judgement of the next rank up; the decision, as always, lies with the boss.

Yakuza Ranks and Responsibilities

While the yakuza hierarchy is simple enough once you grasp the oyabun-kobun relationship and its intricacies, it is just the beginning. Since the average yakuza organisation is built similarly to a corporation, many specific ranks and positions are used to denote seniority, responsibility and influence.

Starting from the very top of the pyramid, we begin with the kumicho. As head of the family, his word is law and his actions unquestionable. All members of the family are expected to revere and obey the kumicho, and do everything in their power to ensure that he is untroubled. It is common for the kumicho to not give literal orders but instead clue his officers in on what to do. This way he can not be directly connected to any crime, which ensures his safety should the police come knocking.

Kanbu – Yakuza Officers

Below the kumicho are the kanbu, or officers, taking the form of executives, advisers and lieutenants. The higher ranks, saiko-kanbu, are generally in close relation with the kumicho. All kanbu are allowed to form families and groups of their own, which means that hierarchies branch off from them as well.

The kumicho employs a number of advisers, komon, that assist him in matters of business, diplomacy and war. Of this little council, the head advisers, saiko-komon, are regarded as the senior members and are directly below the kumicho. Most of the administration is handled by these advisers, with help from specialists such as law advisers, shingiin, and accountants, kaikei.

Equal to the saiko-komon in rank, the so-honbucho, or headquarters chief, takes care of the family's main office and logistics. The so-honbucho prepares vehicles and plans trips, and have been known to serve as quartermasters when the organisation goes to war.

The first tier of officers below the kumicho and his advisers is comprised of gashira, lieutenants. Of these, the kumicho chooses one as his second in command; this individual is referred to as the wakagashira, or first lieutenant, and is supported by a fuku-honbucho, who acts as advisor and assistant. The remaining gashira are regarded as shateigashira, second lieutenants, and operate in other areas of the organisation's territory.

Kumi-in – Yakuza Soldiers

The “working class” of the yakuza, kumi-in, soldiers, are the kobun of a gashira or other officer. They handle most everything that needs to be done; driving, manning telephones, patrolling territory, cleaning, supervising apprentices... In addition they sometimes work in one of the businesses controlled by the organisation or provide protection for such venues.

This tier of the yakuza organisation is the most numerous, generally forming some fifty-five percent (55%) of the total number of members. Kumi-in are not allowed to form any branching families or take initiatives without a go-ahead from their boss, making them the employees of the yakuza corporation. These are the members most commonly encountered by civilians and police.

Jun-kosei-in – Yakuza Apprentices and Partners

Being a jun-kosei-in, or trainee, is not the most exciting way of life. Long hours, little to no pay, constant pressure from above and thoughtless obedience is what can be expected by those aiming to join a yakuza family. Used for menial tasks and as tools, the jun-kosei-in have little else to do but work hard and hope to be admitted into the organisation.

Normally, a jun-kosei-in is not paid but rather taken on as a volunteer of sorts. Due to the working hours being long (sometimes from six in the morning to midnight!) and there being no salary, they often live with parents, girlfriends or in one of the organisation's offices. It takes a long time to be accepted by the yakuza, and some jun-kosei-in remain in their position for over half a decade. Even after being moved up to the rank of kumi-in their salary is rarely above minimum wage.

There is, however, another group of individuals that share the “rank” of jun-kosei-in. These are the shuhensha, associates that enjoy a business relationship with the organisation while remaining outside it. The most common group within the shuhensha are the kigyo shatei, business brothers, who profit from maintaining various deals with the yakuza. They act as fronts, run legit businesses with yakuza funding, handle the economical aspect of cons and extortionist practices, and so on. Informers, black market contacts and enterprising politicians fill out the shuhensha ranks.

Making Money – The Yakuza Business

If there is one thing all criminal organisations have in common it is the almost uncanny ability to devise new ways by which to make money. The yakuza in particular are legendary for working everywhere from below street level up to corporate boardrooms. All ways of making money, be it hustling, extortion or gambling, are referred to as shinogi, an old term that roughly translates as “up against the wall”. While the original meaning was to find oneself at the end of one's rope and being forced to rely on crime or dishonourable business to survive, in the world of the yakuza it has taken on a new life.

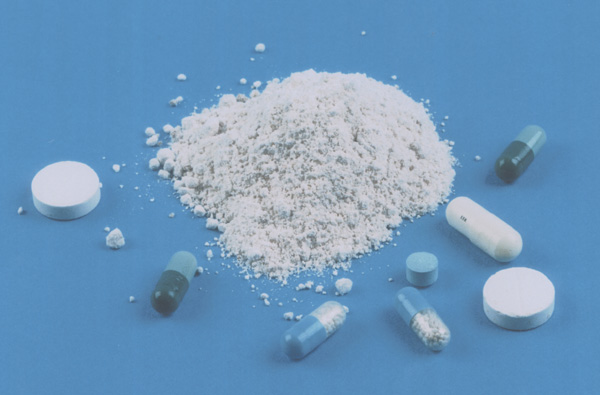

At the most basic level, yakuza engage in the traditional trades; gambling, prostitution, drugs, buying and selling illegal goods, etc. While gambling was the big source of income for early yakuza, it has since been eclipsed by the drug trade. Post-war Japan was so loaded with amphetamines (originally meant to be used as combat drugs) that some yakuza groups could literally appropriate it by the metric tonne. To this day, shabu, Methedrine, remains the drug of choice among the Japanese; it is present in every echelon of society, as a party drug, appetite suppressant and simple pick-me-up for stressed students. Cocaine and heroin has never taken hold in Japan, due in fact to a deal between the yakuza and the government, where the latter promised to turn a blind eye to the amphetamine trade if the former would keep these heavy drugs out of the country. The yakuza have kept their word, and both cocaine and heroin remain 'luxury' drugs.

Amphetamine(c) – now at your local yakuza dealer!

Prostitution is a dark and unpleasant side of the yakuza business. Many groups have made fortunes off of trafficking young girls from the rest of Asia, most of which are lured to the country with promises of a job or Japanese citizenship. While attempts have been made to put a stop to this modern slavery, many politicians have been implicated over the years as having taken part in trips to hotels and cruises on ships offering the company of young girls. While these accusations may be unfounded in many cases, enough evidence exists to suggest that many powerful politicians would prefer the matter of prostitution be swept under the carpet entirely.

Apart from these standard “services”, the yakuza joined the rest of Japan in the hunt for liquidity during the economic revolution of the 80s. When real estate prices sky-rocketed during the development years, many yakuza turned to the landshark business, becoming known as jiageya (literally “one who drives up land prices”). Through more or less sophisticated means these entrepreneurial gentlemen acquired land for construction projects which was paid for quite handsomely. In many cases simple threatening or violent bargaining was used, but the more refined jiageya devised ingenious methods such as walking around the block with a half-dozen angry dogs all day, or, in one case, opening a chicken farm with hundreds of hens in a backyard, letting the noise and smell of waste drive the neighbours out.

As the economic bubble reached its critical point, stockholders' meetings all over the nation were invaded by yet another new breed of yakuza: the sokaiya, corporate blackmailers. Since Japan is a country where honour and a good name makes or breaks your career, disturbances at official events like these stockholders' meetings can spell disaster. The sokaiya, having bought a single share of stock and thus earning access, arrived in droves at the meetings and proceeded to shout obscenities, accuse the board of various forms of corruption and generally misbehave. The panic these men created would cause the stock value to plummet, costing companies millions of dollars. Today, it is common practice for bigger companies to pay a neat sum to the local yakuza groups to have their sokaiya 'take the day off'.

Yakuza inspiration does not stop here, of course. Other common practices include renting out plastic plants for $500 a month, organising illegal immigrants into construction crews, running insurance scams, selling “teenage schoolgirl panties” (bought by the truckload from China and carefully spritzed with a saline solution), sending fake invoices, tricking bankrupt individuals into signing long-term loans, and, strangely enough, running completely legitimate businesses in accordance with the law. In short: if there is a way to make money, legally or illegally, there is likely an expert at it among the yakuza.

Yakuza Fun Facts!

-In 1960, US president Dwight D. Eisenhower had been invited to visit Japan, but socialist demonstrations and rioting had left the Japanese government worried that they would be unable to protect him. They contacted Yoshio Kodama, the de facto leader of the rightist yakuza of the time, and requested his support. In three days, Kodama raised an army of 28 000 yakuza, thugs and volunteers; enough to line the path of the presidential motorcade. In exchange, the Japanese prime minister officially signed and endorsed Kodama's memoirs - the signature was included on the first page of the printed version.

In the end, Eisenhower's visit was cancelled.

-The Yamaguchi-gumi, the single largest crime syndicate in the world, even openly shares the names of some of their more prominent hitmen (Japanese word for a yakuza hitman - and their official title - is hittomanu). Their full names are available on Wikipedia, and these are active enforcers.

-The ritual act of cutting off a joint from the pinky finger (known as yubitsume) is actually a form of apology or punishment expected of a yakuza who fails in his duties. It is usually done voluntarily, but more proactive bosses may present you with a knife and some white paper to wrap the result in. For the ritual to be considered complete, your boss must accept the severed joint in person.

Why the pinky? Well, when wielding a katana or other japanese sword, you grasp the hilt strongly with the small fingers; as such, losing a joint off the pinky weakens your grip substantially. This forces you to rely more on your comrades in fights, which motivates you to remain loyal and work harder. Yubitsume does not end at the pinky, however; if you continue to screw up, you are expected to keep offering finger joints. Bad enough at your job, and you will end up with stumps on your hands.

-When Yamaguchi-gumi and the Ichiwa-kai (a Yamaguchi-gumi offshoot) started the now legendary Yama-Ichi War, the police were initially hesitant to get involved. The war went on for four years between '85-'89, but only thirty-six yakuza were killed in the over two hundred recorded gun battles. The police finally intervened after a shipment from the United States meant for the Yamaguchi-gumi was intercepted by the customs authority. Its contents? Dozens of crates containing grenades, heavy machine guns and reusable rocket launchers.

The war ended in a Pyrrhic victory for the Yamaguchi-gumi, with many of its prominent members arrested in the subsequent crackdowns. While some Ichiwa-kai members sought police protection, the majority were readmitted into the Yamaguchi-gumi and matters settled in the Japanese way - everyone apologised and returned to work.

-Yakuza tattoos, a heritage from the bakuto, are used both for decoration and as calling cards. In general, any Japanese person with a back or shoulder tattoo larger than a few inches across can safely be regarded as a yakuza. This has lead to many bathhouses and other "bare torso" areas to have special signs that forbid individuals with tattoos from entering; the sign generally depicts the stereotypical yakuza with a punch perm haircut and full back tattoo.

The tattooing itself is no pleasant procedure either; it is traditionally done by hand with a bamboo needle, something that is a good five times as painful as any tattoo gun. The work can take years to complete over dozens of sessions, and prominent tattooists only place their work on men of reputation and good standing. To have your back adorned with a master's work is usually more than enough to earn the respect of your peers.

-The word yakuza originates from gambling, as it is the absolute worst hand attainable in the blackjack-like card game Oicho-Kabu. The syllables ya (8), ku (9) and za (3) add up to twenty, which in Oicho-Kabu is a worthless hand. The term yakuza is therefore often translated as just that - "worthless".

Due to 893 literally spelling yakuza in Japanese, the number has been used as a reference for a long time. Protection money is paid out to "Customer #893", many hotels either do not have a room 893 or it is always "reserved", and in Yakuza a secret end-game quest earns you... yes, 893 experience points.

-On January 17th of 1995, a massive earthquake shook the Japanese city of Kobe, turning much of the city into a disaster zone. The Japanese government, stunned by the event, took several hours to mobilise an organised response and was even then blocked by the damage caused to roads and other infrastructure. Luckily for the inhabitants, a certain yakuza group had its headquarters in the city.

Less than an hour after the earthquake, the Yamaguchi-gumi's Kobe members headed out onto the streets with blankets, food and water for the victims. They used their cars to transport wounded to the hospitals and evacuation zones and even deployed a helicopter to search for stranded survivors and organise rescue operations from the air. Their efforts saved dozens of lives and was lauded in the press as what the government should have done but was too incompetent to manage. In the months to come, the group donated millions of dollars to charity and reconstruction efforts.

Of course, this ensured that the construction contracts went to companies closely connected with the Yamaguchi-gumi, and it is generally seen as bad form to mention that the helicopter did not actually belong to them.

-The Chou-Han dice game (as seen in Chapter 7) was the game that paved way for the bakuto, or gambler, class of yakuza back in the 16th century. Traditionally the person in charge of the dice is only allowed to wear cloth wraps on their torso, both to ensure that no cheating takes place and to show off their tattoos. The tattoo was the mark of a gambler, and inspired trust; since gambling was illegal, anyone who willingly displayed their tattoos like that took the brunt of the risk involved. If a group of officials raided the gambling hall, they would be the primary target.

-Japan, with its strong sense of tradition and spirituality, has many festivals during the year. The people responsible for the layout of festival grounds and what stands get the good spots are, of course, the yakuza. The tekiya, or 'peddler', division of the yakuza takes great care in keeping order on the festival grounds and help out setting things up and taking them down. Money is made by selling cheap baubles and toys at inflated prizes; this is commonly referred to as the "peddler tax" and is something the festival-goers expect.

In addition, many yakuza take great pride in participating in the festivities during some festivals. They can be seen carrying portable shrines, competing in sumo matches or leading the local teams. Of course, some may be sore losers, and it is par of the course for rival groups in an area to take the chance to poke a few eyes or land a few nutshots when the opportunity arises.

Showing off your tattoos is normally taboo, but not during a festival!

Back to Index