Part 3

"In Egypt, winter is the best season for fighting but here it is a killer." Acestes warned Heruben. "We must draw contingent plans, in case we fail to capture Calleva before the weather makes siegecraft impossible."Heruben understood his brother's concern. In these strange lands, Summer was short indeed and his army had spent all of it marching and fighting. Now, only a day's march from Calleva, the weather had begun to foul. Already in some places, the snow was waist-high. "Should we be unable to maintain a siege through the weather, the countryside around the river Plowonida Thames, to the south, seems hospitable." Heruben started flipping through the cartographer's scrolls. "We could move our headquarters to the nearby community farm, a backwater village with a well. Ah, here's the map, the place is called Lond-"

"My lord, you sent for me?" Both Heruben and Acestes stopped, looked up at the man who had been shown into the command tent. He was a short, heavyset man with fair hair and skin, clad in a traveling robe of native design. He was quite obviously a Briton.

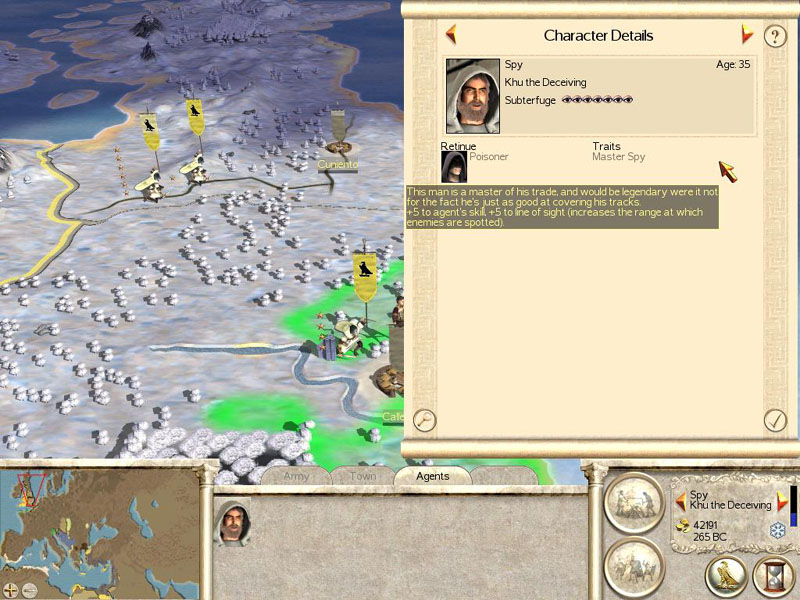

Acestes was obviously startled. A vast majority of the inhabitants of these lands had rejected the rule of the Ptolemies, tenaciously. A small number had ignored or tolerated the egyptians. Never had he seen one speak directly to the pharaoh, much less in perfect greek. Heruben, bemused by his brother's reaction, waved the visitor forward. "Yes, Khu, we were just reviewing some of your more recent work," he said while gesturing to the maps. "Acestes, this is Khu Eng, master spy, and master of first impressions," he added lightheartedly. "He and his family have served the Ptolemies since the days of Alexander the Great."

"Litharge, my lord." Khu Eng replied, pulling a jar of the white powder, Lead Oxide, from his robe. "Disguises the skin, and doubles as a poison in a pinch."

"Khu, your efforts in Britannia have been invaluable to the Ptolemaics. You have provided us with reconnaissance on our enemies, all of maps on the land, and detailed information on their settlements. Already the men are beginning to call the surrounding countryside 'Eng's Land.' "

Again, Khu bowed politely. "I do what I can, your majesty. When you have learned to love what you do, you shall never again work a day in your life."

"You know almost everything in these lands. So you must know that when we left Alexandria, so long ago, we did so upon news of my father's death and without ceremony. I am Pharaoh in name only, as I have yet to be officially crowned. After Calleva is ours, however, I will finally have a land to rule. There I shall make my capital, from which the influence of the Ptolemaics shall spread to the corners of the world. I would like to honor you by naming this land after you. I can become the Pharaoh of Eng's Land."

Khu Eng smiled cryptically, and then shook his head. "Like it or enjoy it, your majesty, but we came to this land of conquerers. As much as we have to bring to these barbarians, we will still need them if we are to survive in this corner of the world. It has been the folly of every failed tyrant in history to rob his subjects of their national identity. Your subjects will be the Britons, and their lands are Britannia."

"Ever are you modest." Heruben said understandingly. Khu wouldn't have given advice unless he felt it was damned important, and he knew the Britons more intimately than any other Ptolemaic. "Very well, Britannia it shall remain. That is all I wanted to speak with you about."

"Thank you, my lord. I will return to monitoring the enemy." Khu replied, bowing once more before turning and heading for the tent entrance. "Besides," he stopped at the flap and turned back to the Pharaoh, "Eng-land is a stupid name for a country."

* * * * *

75 miles to the northwest, Arrhidaeos Ptolemy and his bodyguards stood atop a hill overlooking the city of Isca Caerleon. So far the inhabitants, a welsh tribe calling themselves the Silures had resisted their attackers tenaciously, but Ptolemaics had constructed battering rams and were now smashing holes in their perimeter.

As soon as the main gate was battered open, the Silurians burst forth out of the gap and fell upon the surprised egyptians.

Yet even before they even had the chance to lower their 20-foot spears, the egyptians attacking the main gate were already surrounded. Though they were destroyed, 5 other phalanxes had succeeded in smashing holes in the palisade wall surrounding the city and entering the city.

They quickly discovered that the natives did not build their cities with narrow streets.

Arrhidaeos Ptolemy watched in horror as the entire first wave, half of his army, was obliterated, its fleeing remnants running for their lives into the wilderness.

Flexibility was a double-edged sword, for in the wide-open streets of Isca, it was now the Silurans' turn to be surrounded and cut down by their foes.

Slowly, the Egyptians gained ground until the Silurans had been pushed back to the village square, their last bastion of defense. Archers close behind them, the phalanxes moved to cover the front and the right flank. "Cavalry, follow me. We are entering the city." Arrhidaeos could sense the trepidation building in his horsemen. Cavalry were for open-field warfare, not street combat. He hoped he hadn't just damned himself.

* * * * *

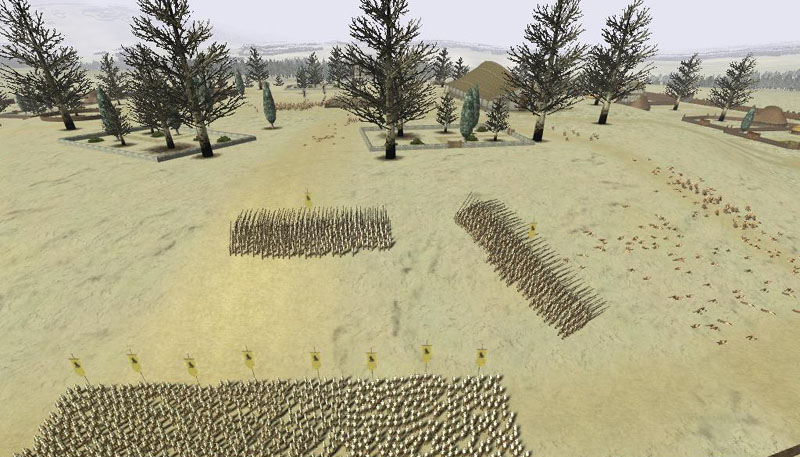

Heruben wiggled uncomfortably in the saddle of his horse, the blasted cold gnawing at the back of his neck. The ground underneath was frozen and the sky had become lead-gray with the approaching winter. This was terrible weather for three thousand men to fight in, but at least they had been given advance warning.

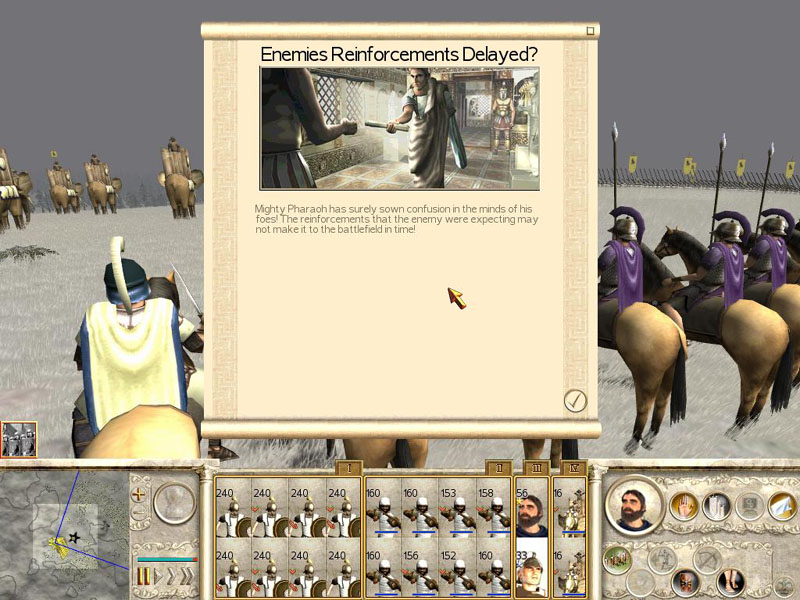

At four in the morning, Khu had ridden into the camp, bellowing over and over again that the Britons were coming. This was confirmed twenty minutes later when the army's scouts reported seeing a huge host of men leave the city of Calleva to attack the Pharaoh's army.

Before Heruben rode out to meet them, Khu had quietly informed him that the Britons were being lead by the dreaded Vortigern, a Gaelic general who had journeyed far from his home in the highlands in order to test himself against the Ptolomaics at Calleva. It was said that he was a giant of a man, standing at nearly six feet in height, with hair like fire.

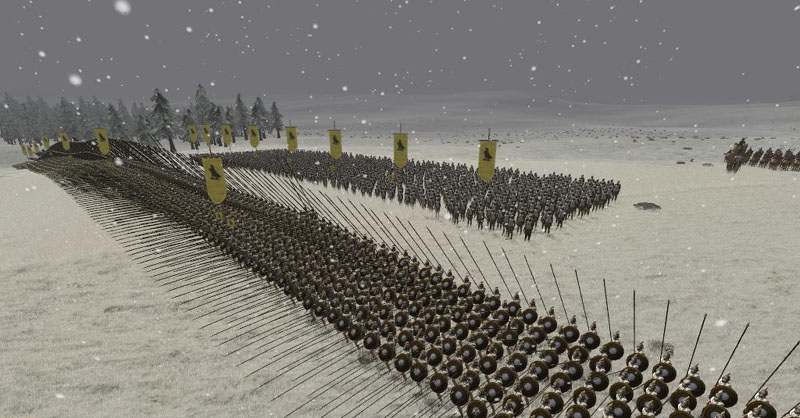

Yes, the phalanx was inflexible, to the point where a soldier couldn't move a few feet out of line without disrupting the entire formation. But who needed flexibility and maneuverability when your men spanned a half a mile? All he could do was wait. Heruben delighted at the thought of seeing Vortigern's horde throw itself against the Ptolemaic line as the Britons had earlier that summer.

The cold wind continued to blow from the south, and Heruben thought that for a moment he heard a musical note carried in the air.

The woad warriors who had been harassing his front line turned and ran like hell.

It was Khu again, who dismounted, spluttering for breath, and running towards the Pharaoh. "Your majesty! Your majesty! The south flank.... forest..." The panting spy was heavily favoring his left leg, and Heruben could only guess at the man's wounds. He looked to his right, to the south. The phalanx was so long, it's right flank extended all the way into the forest.

"Khu! Are you hurt? Speak, man, speak!"

"Those beasts, they're unstoppable! Vortigern attacks from your right! We haven't a prayer!"

Again, the eerie musical notes drifted across the battlefield. This time, Heruben recognized them as the pan flutes the Gaels used to coordinate their formations from afar. He had been completely outmaneuvered. "Riders!" Heruben summoned his command relays, "Tell the men to move formation! South, ninety degrees shift! move!."

The riders sped down the line, blaring their trumpets and the enormous phalanx slowly began to shift as thousands of men moved in formation. Heruben cursed his mistake. A phalanx this large had a turn-radius measured in city blocks. The wind blew again, and all he could hear was the blaring of a hundred flutes, joined by the screaming of men.

And then, emerging from the forest, four thousand barbarians descended on the egyptians' right flank.

* * * * *

The winter of 265 BC was the darkest season yet for the Ptolemaics, no news had come from Egypt in quite some time, and it was assumed that all of the former Egyptian holdings had fallen under the rising Seleucid tide. Arrhidaeos had succeeded in conquering Isca, but in doing so had sustained appalling casualties.

To the east, only 10 miles from their destination Calleva, the Pharaoh's army had been crushed by the Gael, Vortigern.

The Ptolemies had come from a long and proud line of tradition and history. They had all been raised in the fashion of greek royalty and hellenic courage. But out in the wastes of Britannia, the rules of survival and victory were different. The barbarian armies had triumphed over the best trained military on earth, heirs of the legacy of Alexander the Great.

Now, more than ever, those of the Ptolemy bloodline were expecting to die.