Part 27

A Four-Method Analysis of the Final Period of the Great Renaissance Era

The Great Renaissance is generally divided into four periods: The Early Period, the Changing Century, the Late Period, and the Final Period. These periods are separated by key events. Here is a short timeline:

- 1200 AD -- Denaturalists found the University of Moscow.

- 1200 AD through 1250 AD -- The Early Renaissance Period

- 1253 AD -- Lord Riv contracts tuberculosis, marking the beginning of the epidemic.

- 1250 AD through 1350 AD -- The Changing Century

- 1350 AD -- Lenin exiles the liberal leadership.

- 1351 AD through 1478 AD -- The Late Renaissance Period

- 1478 AD through 1481 AD -- The Russo-Spanish War (Now called the Three Year War.)

- 1481 AD through 1581 AD -- The Final Renaissance Period

- 1582 AD -- Russangxi Nationalists dismantle the Russian Civil Service.

Part IV: A Political Analysis of the Final Renaissance Period

by Georgi Malenkov

There is no greater nation than ours. Mythic kingdoms pale in comparison. Medieval hyperboles fall short of the modern truth. There are as many people alive right now as lived during the rest of human history combined. Every day, Moscow consumes more food than the Grand Duchy of Parthian once ate in a year. If agriculture stopped tomorrow, our planetary reserves would empty in 48 hours. Our citizenry is the entire human race, and we need help, always.

We require support, organization, and leadership, or the state will break and we will starve. Our party system provides us the stability and training necessary to keep that system running--to keep us fed, healthy, and warm.

In today's history file, I'll tell you the story of this system's birth, an event we call the First Cultural Revolution. Its completion marks the transition between the Final Period of the Great Renaissance and the Industrial Era.

The Political Repercussions of the Three Year War

]

]The Taoist Monastery burns while the Aide to the Executive, Masr Golyi, surrenders to Tsar Krasny Kavkaz on behalf of Parliament.

The official date for the end of the Three Year War is April 11th, 1481, almost a year before Davydov conquered Madrid, and long before Traitor Nilus was captured in the Sacking of Seville on November 30th, 1482, the first Nilus Day. Aberrant historian Mark Azadovskii noticed this discrepancy in 1624 while searching for the identity of Nilus's infamous "Historian," the alleged engineer of the Three Year War. Today, you probably know the Historian as the Phantom Liar. Why did the war officially end before Davydov's campaign did? Why did one and a half centuries pass before the discrepancy was discovered?

Prior to the war with Spain, Tsar Krasny Kavkaz was engaged in a quiet but significant conflict with Parliament. To understand his trouble, you need to know a little about his grandfather Casimir Kavkaz, a little about his father Sergei Kavkaz, and a little about the Liberal Letters.

During the reign of Tsar Casimir Kavkaz, the crown's opinion had inevitably become law. Casimir was a popular figure and an erudite scholar. He was unquestionable. When Sergei took the throne, the opposite was true. Sergei was a disinterested Tsar, and he left the operation of the state to Parliament. Because these first reigns were generally peaceful and efficient, the question of dominance was ignored. The Liberal Letters were lauded in academic circles. A major flaw was ignored: the Letters had no provision to cleanly resolve conflicts of executive power.

By the time Sergei retired, The Executive of Parliament, Luka Ivanov, had grown used to having the final word. Sergei's successor and son, Krasny, admired his grandfather greatly, and he expected the same deferential treatment from Parliament that his grandfather had received. In general, this wasn't a significant problem. Most issues before the government were simple, and Luka and Krasny agreed on their solutions. In these cases, Luka smartly stood silent and granted Krasny full credit for the decisions.

But regarding the public treasuries, the executives couldn't disagree more. Luka planned to expand the bureaucracy to compete with private accounting firms and banks. Krasny coveted most of the budget for the training of officers, the salaries of professional soldiers, and the expensive equipment of contemporary military brigades. There wasn't enough money for both men.

In 1480, Luka eyed Krasny's expenditures and decided that they ought to be appropriated for his liberal projects. He tried to shame Krasny into conceding governmental control. Luka believed there wasn't a war in the foreseeable future, so he publicly decried Krasny's military spending. He wrote and distributed a big-letter poster. It read,

The danger isn't readily apparent to a modern reader, so let me elaborate.Luka Ivanov posted:

Hear the jingle of the tax-man? That's your coin in his purse. At oath, Tsar Krazny swore to spend every kopek on your behalf. He honestly believes he does, but as any man of reason knows, he doesn't. A swarm of swindlers coerces him to prepare for war in a time of peace. Help the Tsar spend your money justly. Tell him to heed Parliament and reduce military spending, or tell the tax man that you won't pay.

At the time, tax evasion was difficult to punish and crime was rampant. Millions of poor peasants locked their doors when the tax-man came. The nobles, guildmasters, plantation owners, and merchants paid some taxes, but their properties were maliciously self-appraised below their actual values. In short, the rich paid less than they really owed, and the poor paid nothing at all.

Taxes were the Empire's lifeblood. When funds were scarce, local governments encouraged payment with festivals, plays, highly visible public works, and other visceral rewards for paying taxes. If that didn't work, they rounded up brute squads and pillaged the local townships. The government was eternally desperate, and the people knew it. Hoping to avoid such bloody crackdowns, the citizens nurtured a hypocritical culture. They openly encouraged paying taxes but privately practiced tax evasion. To admit this hypocrisy or threaten its stability was taboo. For this reason, it was unheard of, even deplorable, for someone with any influence to decry taxation. For nationalist ideologues like the Denaturalists, it was tantamount to treason.

The outcry was immediate, but Luka was prepared. He directed his supporters to deliver speeches on his behalf. While carefully sidestepping the subject of tax evasion, Luka outlined the Empire's foreign policy. The populace was only dimly aware of actual international relations, and their ignorance played into the his hands. Despite Spain's aggressive behavior north of Crimea, his message was, "It's all safe on all sides. Russia is at peace with her neighbors. Krasny shouldn't prepare to fight them. He should leave the money for the people."

Because Krasny was busy handling the Dukes of China, he hesitated and lost his chance for a quick resolution. He didn't respond to Luka until Parliament reconvened the next year. During the five-month interim, Luka continued to consolidate his position. He founded a federal news department, Agitprop, and headed the department with his second-in-command, Aide to the Executive Masr Golyi.

"Agitprop" stood for "Agitation and Propaganda," but not in the way that we know these words. Agitation meant grabbing the attention of an uninterested People. Propaganda meant distributing important knowledge. In this way, Agitprop was a primitive State News File. Lies weren't associated with its name until the Final Cultural Revolution, though Luka lied in its founding months. Russian diplomats relayed rumors of the Spanish military assembling in Cordoba. Russian spies couldn't locate the queen or her generals. Russian intelligence officers supposed that they were preparing for war. Nevertheless, Agitprop said, "There is universal peace."

Because the Tsar had failed to react, more members of Parliament assembled behind Luka. The initial taboo, already broken, faded in importance as the months passed and the People began to believe Luka's message. That year, almost no taxes were collected in the old duchies. Publicly recognizing the reduced income, Parliament reconvened in February in order to reduce expenditure and account for the public treasury. It seemed they were going to cleanly eliminate Krasny's influence on the budget as a matter of course.

What they didn't know came back to hurt them. Though Krasny hadn't responded for months, he hadn't wasted the days either. Almost immediately after Luka printed his first big-letter poster, Krasny left Moscow and made a two month overland trip to Shanghai. Because time was critical and travel was slow, he rushed through a three day meeting with influential Chinese and Russangxi Denaturalists. These men, bankers and merchant moguls, offered money and political support, but they demanded a high price from the Tsar. Krasny had to promise that the military would not request supplies or war equipment from the Chinese provinces during Krasny's reign. Why didn't they want to pay for a war? Why was war on their minds?

To the attentive reader, it might seem that the Denaturalists knew about the upcoming war. Let me assure you, they didn't. Krasny's promise benefited them under any conditions. Even in peacetime, investing in military supplies was an economic loss. As one banker selfishly wrote, "Capital invested into a business will renew itself and draw gold. Capital invested in a gun will burn up in a puff of smoke."

Be certain though, that these men expected war. They were privy to the same rumors as the Tsar, and as Denaturalists, they planned to support Empire in case Spain moved against Crimea. Reluctantly, Krasny agreed to their demands and returned to Moscow with a caravan of accountants representing the Chinese banks. Upon arrival in Moscow, the banks graciously donated a vast sum to shore up the lost taxes. Immediately, Luka's Denaturalist supporters abandoned him and took a neutral stance. If Krasny were able to dominate Parliament, then they would not work against him. But if Luka were able to maintain his grip, then they would not hinder him either. They simply waited to choose the winning side.

Infuriated by the wavering support, Luka assembled an address before the palace. In a half-hour speech, he laid out the opening salvo of a violent political battle. Here is a transcript of the final seconds.

Krasny spent two days crafting an official response. He wrote a pamphlet called Pravda, the Russian word for truth. Within its pages, he relayed digests of military reports and laid out the history of Russia's relationship with Spain. He published the full text of Isabella II's letter to Casimir Kavkaz, and he included rumors of military movements in the Crimean wilderness. He concluded with a fascinating piece of social engineering. Rather than pleading for the People's approval, he simply declared that Parliament failed to act in the People's interest, and that he would "henceforth take absolute executive control as an emergency measure." In line with this declaration, he ordered General Davydov to assemble an army and prepare to move towards Crimea within the week.Luka Ivanov posted:

[Luka holds up a gold kopek above his head]

So, here it is! The pocket change of Chinese bankers. It's money, taxes, debt. How should I use it? How should I spend it? I think this money from the People should be used for the People. Nothing else would be appropriate. Yet Tsar Kavkaz has different plans. He prepares for war. He will take this boon, this generous donation, and he will spend it frivolously. He will buy cannons, grenades--expensive, fragile toys. He will buy weapons, when we need plowshares!

[pause to hear the crowd cheer]

Are you the People?

[crowd response: affirmative cheers]

Who rules Parliament?

[crowd response: more cheers]

There are men who fear the Tsar. They wait in the wings. They refuse to work on your behalf. Do you know who these men are? No? They are your representatives!

[crowd response: cheers bordering on mob frenzy]

Men, women, we will have restraint! Restraint! We will not take Parliament unjustly. Restraint! If they will wait, we will wait. Restraint!

[crowd response: volume drops until Luka's voice can be heard]

Men and women of the People. Today, by hearing your voices, you have told your governors what you desire. To the members of Parliament, you have reminded them that they represent you. To Kavkaz and his supporters, you have said, "Spend the money on the People--or else!"

[cheers continue until Luka leaves the platform]

The publishing of the Pravda surprised Parliament as much as it surprised the People, and though there was some official protest against the Tsar's military deployment, it was ineffectual. Resistance was conflicted. Local political commentators were divided--royalists approved and liberals disapproved--and as a whole, the People showed little ability to act. The military deployment simply compounded the problem. Many of the professional soldiers were eager to campaign and earn double wages, and none of them wanted to see this political conflict resolved before they'd left Moscow and earned some field pay.

Luka realized that Parliament would only stay relevant if it conceded the political battleground to Krasny but maintained executive control. On the next Saturday, when the Taoists relaxed in prayer, he convened Parliament in an emergency session and laid out a defensive, cost-effective strategy against Spain. Essentially, he conceded that Spain was moving but refused to declare war. He expressed "strong disagreement" with Krasny's emergency measures and chastised the Tsar for withholding "valuable diplomatic and military reports." Essentially, he acknowledged that Krasny was right, but he refused to let the Tsar officially deflate Parliament's role.

Despite Luka's effort, Krasny continued to consolidate his power base. He called on independent members of Parliament and bribed them with Chinese gold. By the end of a fortnight, Krasny had enough of Parliament in his pocket that he could guarantee gridlock and potentially win contested votes.

Luka prepared another response, a speech. It was part of an increasingly desperate plan to draw public pressure on Krasny. He saw the Tsar's power conglomeration as tyranny. Unfortunately, before he could deliver his blow, "The Hedonist" was published by an anonymous Crimean Jew. It detailed the gruesome sexual deviancy of Isabella III and painted a lurid picture of a slaughtered Jewish township. Krasny capitalized on the People's momentary rage and declared war on Spain. To avoid appearing as traitors, Parliament quickly legitimized the declaration with a unanimous vote to "protect Crimea at all costs."

It's simplest to compare the war's course with Luka's influence. While Davydov marched to Cordoba, Luka's power waned. He and his supporters hid themselves in the Taoist Monastery of Moscow and spent much of their time collecting information about the war. They were looking for a mistake they could pin on Krasny. Luka's position improved as Davydov approached Barcelona. The effects of the war seemed negligible, and the People's interest receded. Once Barcelona fell and the news reached Moscow, Luka's position waxed full like the moon. He had a chance to discredit the war effort, and he took it.

Madrid was the next target in Davydov's campaign. It was considered extremely difficult to conquer, if not impossible. Traitor Nilus commanded their defenses; Madrid's ports couldn't be blockaded for at least a decade; and Spain was assembling the largest defense force yet seen in human history. Even with the fully mobilized Russian military at hand, Davydov would be outnumbered 3 to 2. Taking a page from Krasny's political playbook, Luka paid out of pocket to publish his own Truth paper, the Russkaya Pravda, or Russian Truth. This paper analyzed the war effort and listed Madrid's forces in excess of 100,000 trained warriors. It broke down the fiscal costs of an extended siege in terms of kopeks per head per household. He claimed that conquering Madrid would eventually cost each family an entire ruble of silver. He tactfully declined to calculate the human costs, but the language of the paper implied grim results. "We'll lose the soldiers," Luka wrote, "not to death, but to decades wasted beside foreign walls. And the war will not be defensive, but pointlessly offensive."

Luka published the Russkaya Pravda in January of 1481. The response was immediate and favorable. Academics rotated petitions in Moscow, Parthian, Shanghai, Grozny, St. Petersburg, and Delhi, to which tens of thousands of names were affixed. The People's will was clear. It was time to end the war to save money and lives.

If nothing else had occurred, Luka would've totally undermined Krasny. 1481 was an election year in Parliament's 7-year cycle, and if the war dragged on until the beginning of summer, Luka would've used it to "clean house." Parliament was rotten with Krasny's money, and it wouldn't haven taken much work to produce evidence against dozens of bribed Denaturalist representatives. Armed with the People's favor, Luka could've had many of the candidates blacklisted from eligibility, if not outright arrested for treason. In effect, Luka would've broken the Denaturalist element in Parliament, opening the door for a liberal majority.

But something else occurred. Krasny was without scruples. By late February, he'd mailed official correspondence to Davydov. Hidden in the text was the following message: "Break Spain within three years. Bring Traitor Nilus to Moscow before January 1485. I'm officially ending the war in April 1481. Combat will continue at your discretion. Requests for supply will not be answered after September 1484. Collect supplies at Barcelona. Do not send soldiers home without sending Nilus first."

In March, Krasny organized the members of a conspiracy. His inner circle included two generals, Semyon Gudzenko and Iosif Utkin, nine members of Parliament, and the Aide of the Executive Masr Golyi. Though Masr was a liberal, he was first and foremost greedy. Bribery put him in Krasny's employ. This conspiracy was designed to accumulate and hide the expenditure of public funds for campaign wages.

Krasny's plan was simple. If you haven't figured it out for yourself, I'll explain. He planned on lying to the public. He would declare the surrender of the Spanish crown and officially end the war. Unofficially, the war could continue. Luka would be discredited, and Krasny could arrest him for spreading panic and dissent.

It may seem hard to believe that Krasny could successfully cover up a war. But that's exactly what he did. On record, Traitor Nilus remained at large, and Davydov's forces were redeployed to police the Spanish provinces and find Nilus. Off record, Davydov was entrusted to conquer Madrid and bring back Nilus before their cover story failed.

Since correspondence between Davydov and the Tsar had to cross the Crimean wilderness or travel through Egypt at great expense, it was supposed that the war would end long before the truth filtered back to the Empire. Some of Krasny's conspirators feared that Spanish sailors might break the news in Saxon or Parthian, but their fears were unfounded. After Cordoba fell, the docks were closed to Spanish traders, and all contact ceased between China and Spain.

An aerial photograph of the contemporary Taoist Monastery in Moscow. It's now a garden on the roof of a skyscraper. In its center is a plaque memorializing the death of Luka Ivanov.

At dawn on April 11th, 1481, Tsar Krasny Kavkaz officially accepted the surrender of the Spanish crown. Within an hour, Luka Ivanov heard the news and panicked. Knowing full well that the war was far from over, he figured that Krasny would come to arrest him and keep him quiet. He collected several of his closest supporters--including Masr Golyi--and hid in Moscow's Taoist Monastery. He barricaded the Monastery's Inner Court--a walled garden--and surrounded it with a contingent of mercenaries and loyal Parliamentary guardsmen. Quickly, he drafted another issue of the Russkaya Pravda. It called for a revolution against the Tsar and the immediate execution of many Denaturalist members of Parliament. It was his war cry against tyranny.

Krasny assembled a military force of his own. In addition to the Tsar's personal guards, Iosif Utkin and Semyon Gudzenko contributed two hundred fully-armed grenadiers. They were given official orders to arrest Luka Ivanov and seventeen other liberal members of Parliament for treason and spreading panic. By eleven in the morning, all but nine of the wanted men had been arrested in their homes. The rest were missing, presumably hiding with Luka. Krasny was temporarily frustrated. He didn't know where to find them. In fact, given enough time, Luka might have published the next issue of the Russkaya Pravda and incited a Civil War. Fortunately (or unfortunately), just before noon, Masr Golyi contacted Krasny with a messenger and betrayed Luka's position.

At noon, Krasny's forces marched down to the Taoist Monastery. By one in the afternoon, they'd surrounded the grounds and made contact with the monks. Luka had requested sanctuary, and the head of the monastery refused to hand him over to the Tsar. Knowing full well that Luka had to be captured and eliminated before he could craft a public response, Krasny ordered an assault on the Monastery. Most of the outbuildings were set on fire, and the monks voluntarily surrendered. Luka, however, refused to leave the Inner Court of the Monastery. He gated and barred all the entrances. Seeing this as an opportunity to legitimately kill a political enemy, Krasny ordered the Monastery to be razed. The general's grenadiers attacked the south end of the inner court with grenades and shortgonnes. After killing sixteen of the pike-wielding Parliamentary guards, they blasted open one of the south gates and extracted Masr Golyi. Afterwards, they set fire to the south end of the Inner Court's garden and moved west to bolster the watch along a tree-shrouded hillside.

By three in the afternoon, the fires had spread through most of the Inner Court's vegetation. Forced to run from the fire, Luka tried to escape through a northwest gate, only to meet Palace guards. His personal soldiers were armed with shortgonnes and sabers, but they were outmatched in both skill and number. After a short firefight, a bullet struck Luka in the lower intestine. The rest of his guard surrendered, and within the hour, Luka passed out from blood loss and died. Two other gonnefights broke out a half hour later, when the rest of Luka's supporters tried to escape the blazing Inner Court. They were pinned down by the generals' forces, and either died from the fire or from grenade shrapnel. In one short, bloody afternoon, the liberal faction was eliminated.

Uphill from the monastery, Masr Golyi surrendered on behalf of the rebels, and on the spot, Krasny pardoned him and awarded him the title of Executive of Parliament. Krasny's control of the executive was complete.

And that explains why the war officially ended before Davydov's campaign did. The Tsar used it as part of an excuse to control Parliament. But why did one and a half centuries pass before the discrepancy was discovered?

First and foremost, it's important to realize that Tsar Krasny's declaration of victory was wholly believed. As expected, news of the fighting in Madrid and Seville didn't reach the Empire until Davydov returned with Traitor Nilus in chains. Nilus, a paranoid delusional, later attempted to point out the improper date, but his raving testimony only served to bolster the Tsar's account. If Nilus believed in the Phantom Liar, why would anyone trust his account of the actual war? Davydov and his soldiers could have revealed the discrepancy, but they were permanently retired to the Spanish provinces and their families were moved to meet them. This led to a few leaks, but the audacity of the truth was too much to be believed, and the rumors of a deliberate discrepancy were ignored. Since Spain used a different calendar, the difference in dates was thought to be a flaw in calculation.

In short, people chose to believe the lie because the truth was too messy and destructive to consider. Eventually, when Mark Azadovskii discovered the truth, Luka Ivanov was posthumously pardoned. But by then, it was too late to make a difference. History had moved on in the last century, and people weren't afraid to look back on their ancestors and think, "They were fools to believe."

Recessions: Old Russia's Poverty, the Tsar's Decline, The Liberals' Death

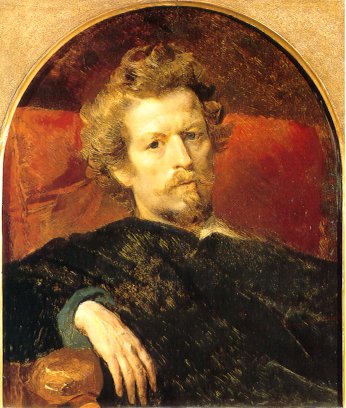

Tsar Krasny Kavkaz, one of the last officially recognized autocrats.

As the Final Renaissance began, the preceding events touched off three trends which survived to the middle of the Period. Historians blame all three trends on Tsar Krasny, but a more accurate assessment is that Krasny injured three institutions, and in the post-war decline, it was inevitable that these institutions would decay. The economies of the Old Russian Duchies recessed; the crown lost its legitimacy as an executive institution; and the Liberal party withered and died. I will review each of these shortly.

Old Russia's Poverty

During the Russo-Chinese War, Tsar Krasny kept his promises to the Chinese bankers. Russian production centers were focused on the war effort, while Chinese and Indian guilds were left alone. Given the freedom to act and access to Russian markets, the Chinese companies produced larger volumes of marketable goods like textiles, tools, and processed construction materials. Without competition from their Russian counterparts, the balance of trade slowly slipped in favor of the Chinese, and the flow bullion drained the Old Russian Duchies of wealth.

Since kopeks and rubles were made of silver and gold, the quantity of coins in Old Russia decreased. This led to a double-whammy of economic crises: the region recessed as production flowed into the bottomless pit of military expenditure, and in the local economies, the kopek and the ruble deflated--each coin increased in value. Debtors in the region found themselves unable to pay back their creditors. Many of the skilled workers fled to find jobs in richer provinces, or if they didn't have any salable skills, they fled to Spain to find any jobs at all.

Parliament might have introduced protectionist acts on behalf of the Russian Duchies, but Krasny flatly refused to impose intranational tariffs. In effect, he left Russia's wounded economy bleeding into the rest of the Empire. Over the following decade, 1481 to 1491, Old Russia suffered one of history's earliest deflationary spirals. Because of deflation, consumers lost confidence in the value of goods. They got the most food and shelter out of each ruble by hoarding it and waiting for deflation to appreciate its value. Because the consumers weren't paying for anything besides food and rent, producers dropped their prices and slowed production to remain profitable. Slowed production led to lower wages, and lower wages led to lower prices. Lower wages and lower prices meant less money for everyone and even greater deflation. It was a vicious cycle with no end in sight.

By the turn of the century, the recession ended and Old Russia began the long road to recovery. Low market prices lured Yangtsen workers back to the Duchies of Moscow, St. Petersburg and Grozny. Cheap resources lured investors and their vast fortunes. These middle and lower class immigrants brought the Russangxi language with them and forced the first step towards ethnic fusion. Since the period of recovery was longer than the period of deflation, Old Russia remained economically disadvantaged until growth rates fully recovered in the 1530s. At the same time, Chinese clearcutting slowed, and the cheap lumber market crashed, slowing growth in the otherwise prosperous Chinese Duchies.

Old Russia regained its glory as the heart of the Empire, but the mark of poverty remained for a dozen decades in its broken streets and fading facades. It wouldn't gleam again until the Renovation and the Final Cultural Revolution.

The Tsar's Decline

Tsar Krasny's grab for power scarred Parliament for decades. Though new faces filtered in and out during Krasny's reign, they had little effect on the day-to-day management of the Empire. After the death of Luka, Masr Golyi had adopted the role of the Executive of Parliament for life, and he'd made himself Krasny's pawn. Without a leader or any executive mouthpiece, Parliament became little more than the vestigial third arm of Krasny's autocracy.

Ironically, this secondary position weakened the crown rather than Parliament. Parliamentary culture was cowed into following Krasny, but in being cowed, they also elevated Krasny and made him unique. In common lore, he was a legend--"the man who defeated the bloody Steel Buddhists." How could anyone hope to follow that reputation? As Krasny and Masr aged, "young" members of Parliament planned to peacefully assume the mantle of the Executive. Krasny's sons were terrible students of politics and totally disinterested in their father's work. It was the People's opinion that nobody could completely fill Krasny's shoes, and Parliament assumed that it would have to carry on his work.

Eventually, in 1542, Boris Kavkaz ascended to the throne. Boris rattled his own personal saber for a few years, but reality impugned his self-importance. The next Executive of Parliament, Mikhail Zadornov, publicly said, "The members of Parliament appreciate your enthusiasm, Your Highness Tsar Kavkaz IV. However, these affairs of state shouldn't concern someone of your importance. We will handle everything. You may retire to your palace."

That was the first public dismissal of the Tsar, but it wouldn't be the last. In essence, Krasny's reputation was so great that the People believed nobody could replace him. By becoming one of the most powerful Tsar's, he had set the cultural stage for a Parliament which believed there could never be another like him. When Krasny left the throne, its legitimacy and importance left with him.

The Liberals' Death

This is the shortest and saddest story in the Final Renaissance. Krasny needed to legitimize his consolidation of power. It was easiest to villanize the former Executive and his supporters. Krasny declared the liberal members of Parliament to be traitors, forced the living members to sign confessions, published detailed and fictional accounts of their crimes, and publicly executed everyone who was arrested on April 11th.

Uncritically, the People believed the Tsar's story. After such a political purge, anyone with clout distanced themselves from the liberal faction. The People still appreciated the liberal ideals, but they quickly and happily denounced the liberal party and called them "unfaithful to the philosophy." For nearly a decade, the only political party was Denaturalist. Eventually, Russangxi politicians, running as part of the independent "Free Market" party, filled in the power vacuum left by the liberals. After that, the liberals' popularity declined rapidly until it terminated in the 1502 elections, when the last openly liberal incumbent declined to run again.

Pure liberalism was dead.

The Decline of the Russian Civil Service

These moldering books are the records of the Russian Civil Service in Shanghai. The last entry was placed in these books in 1584, before the office closed. They are awaiting scheduled attendance by the World State before 2071.

Mikhail Zadornov was the Executive of Parliament between 1523 and 1565. He was a precocious politician. His guild district elected him to his first state position, District Representative, when he was only 17. Six years later, at the age of 23, he passed a bar exam at the University of Moscow and became a prominent Denaturalist lawyer. At the age of 29, he quit his practice to run for Parliament and won one of Grozny's two-dozen seats. Three years later, Masr Golyi retired because of a heart condition, and Mikhail ran for the Executive position. He lost to Pavel Borodin, but Pavel withdrew from the race because of an attack of catatonia. He conceded victory to Mikhail, who won only because his competitors had wasted their votes on Pavel. However, Mikhail proved to be an excellent Executive. He kept the position for six terms before retiring because of illness.

Zadornov's most important contribution to history was his willingness to hire private contractors for state jobs. This set a precedent and is considered the primary cause of the decline of the Civil Service. He introduced the Notary Bill of 1527 and created the cottage industry of middle-class civil servants. These private notaries were authorized to resolve issues of private law, authenticate wills and private settlements, witness contracts, convey property, and handle matters of succession and estate. He wrote the 1544 Public Works Contracting Bill and opened the door to private construction companies working on public works--irrigation ditches, aqueducts, public plumbing, roads, public buildings, and the like. In 1563, he proposed an amendment to the Liberal Letters decoupling the Civil Service from the court system. Unfortunately, while this amendment failed to find ratification in Parliament, it was not a lost effort. During the First Cultural Revolution, it inspired the separation of civil and criminal courts, the introduction of appeals, and the judicial power of interpretation--"the legal capability to reinterpret or dismiss the letter of the law in mitigating circumstances or situations of unusual merit."

Pobisk Kuznetsov

Though Pobisk Kuznetsov is best analyzed in a sociological context, he is worth discussing as a minor political figure. Between the retirement of Executive Zadornov and the rise of business mogul Ivan Bunin, there was a decade when Pobisk Kuznetsov was the center of public attention. His main attraction was his incredible speaking voice--in an era without electronic amplification, his loud, clear words carried well over large distances and boisterous crowds. Furthermore, his natural training was as a linguist, and he spoke almost two dozen languages with near-fluency. He toured the Empire and spoke to the People in their native tongues while advocating a massive sociological shift. He undeniably influenced the adoption of Russangxi in most of the major cities in Old Russia, India, and China.

Thanks to him, Ivan Bunin had an audience.

Ivan Bunin: Father of the First Cultural Revolution

One of the earliest photographs in the State Archives, this silver-plate photograph of Ivan Bunin shows that he was descended from Moskva parents.

Little is known about Ivan's lineage, but he was undoubtedly taught Russangxi as his native tongue, and he knew only passable amounts of Russian and Chinese. He was born somewhere in China, probably Shanghai, but he left his family at the age of 13 and moved to Barcelona to find work with one of the Russangxi entrepreneurs.

During his stay, he changed jobs every few months for almost three years until he met Gregoria Apaza, the rich daughter of Jesu Apaza and Alla Sizova. He married into her family and inherited Jesu's Russangxi business, a major Spanish road-building firm. Jesu's workers had graveled almost every major road between Barcelona, the coast, the Moskva River, and the Doñana Industrial Park, and they had the manpower to build roads between the local townships and provinces. At the age of 19, he took over the business and began building a circle of contacts in high places.

In 1574, Gregoria's cousin Luis Apaza was elected mayor of Barcelona. Ivan took this opportunity to broker a landmark deal. After using his family relationship to contact Luis, Ivan offered to build and maintain a highway from Barcelona to Crimea if Luis invested part of Barcelona's tax revenue in the development. He promised to tariff interprovincial traffic and pay part of the road's profits back to Barcelona, keeping a small portion for himself and paying the rest back to any other investors he could find. Luis was reluctant, but Ivan was convincing. He pointed out that Civil Service barely appraised the condition of Spain, let alone sent workers to develop its infrastructure. If anyone was going to rebuild the conquered provinces, it would be the People. Luis accepted Ivan's offer under the condition that he wouldn't pay for any of the road built in Crimea.

With Barcelona's gold in his account, Ivan contacted three Crimean bankers--Alexander Bayanova, Yuri Samoylov, and Vadim Mayarchuk--and made a similar offer. If they paid for the Crimean half of the highway, he would pay them a small share of the tariffs collected in trade. Samoylov agreed immediately, but Bayanova and Mayarchuk only agreed under the condition that their caravans would not be tariffed along the road. Ivan signed all three onto the deal with a public notary, and began construction of the highway in 1576.

Construction continued without hindrance until 1579, when Duke Lerrmontov of Crimea arrested two of Ivan's contractors while they were surveying unclaimed land near the White Hills north of Crimea. They were released a week later, but though their lives were spared, the damage had been done. They'd inadvertently drawn the Duke's attention to Ivan's trans-Crimean highway. The Duke was head of the local Civil Service, and he was furious to learn that Ivan planned on privately building and taxing a road along the Crimean border. He wrote Ivan a letter demanding that "Bunin-Apaza's company and associated workers must abandon the road for salvage by me, Duke Vasili Lerrmontov of Crimea, and the Russian Civil Service. If Ivan Bunin or associated workers refuse my request, I will arrest them for crimes against the Grand Duchy of Crimea."

By this point, the Duke's title was mostly honorary. In all but a handful of provinces and duchies, the Dukes were inconspicuous or bankrupt. Dukes had little to do with the actual business of the Russian Civil Service, and in a general sense, the title of Duke was only legally transferred out of a sense of tradition. Nobody had seriously exercised the power of the Duke for nearly half a century, and for Ivan's generation, the letter was a meaningless threat.

Ivan threw aside the letter and continued construction without hesitation. Unfortunately, Duke Lerrmontov could bite. The Grand Duchy of Crimea was underdeveloped, and the Duke was still rich enough to be the creditor of a tenth of the Crimean peasantry. Unwilling to let the banks eliminate him, Lerrmontov had repeatedly used his waning political power to quash economic interests and infrastructural development. He realized that his power inversely correlated with progress, and he wouldn't go gently into obsolescence.

Lerrmontov rounded up an armed posse of thirty men and arrested the contingent of Ivan's workers in Crimea. He then mailed another letter to Ivan, and threatened to execute the head of Ivan's Crimean contingent unless Ivan stopped construction and handed his contract over to the Russian Civil Service.

Enraged, Ivan personally left Barcelona and traveled to Moscow, where he pleaded to have his case heard before Parliament. When Parliament's current Executive Evgeny Shvarts read the secretary's summary of the argument, he became intensely interested in the previously unknown conflict between a private contractor and the Duke of Crimea. Since Lerrmontov was considered something of a troublemaker, Evgeny hurried the case into session and had it put to vote in less than two days. Lerrmontov wasn't even given enough warning to appear in his defense, and Parliament ordered him to release Ivan's workers and to cease and desist harassing Ivan and his associates.

Duke Lerrmontov learned about the case at the same time he received its ruling. Appalled at what he thought was an outrage of due process, he not only denied the release of Ivan's workers, but he arrested Ivan in Crimea and demanded him to sign a release giving the highway project to Lerrmontov. Ivan refused, so Lerrmontov tortured him by making him sit in the jetliner position for nearly twelve hours. When Ivan finally signed the release under duress, Lerrmontov rounded up a military response and went to arrest Ivan's company in the Crimean wilderness. Lerrmontov then tossed Ivan in jail, where Ivan waited for seven months.

Ivan's wife, Gregoria, sent a letter of protest to the Executive of Parliament. After two months on a secretary's desk, the letter reached Evgeny. When he learned of the gross injustice, he ordered General Utkin II to march with a full brigade of grenadiers. If the Duke refused to release Ivan and his associates, then Utkin II was commanded to overthrow Duke Lerrmontov and free Ivan by force.

In 1581, Utkin II arrived in Crimea and delivered his demands. Lerrmontov didn't outright refuse to comply, but he bandied words for time. He secretly hoped to execute Ivan before the general removed him from prison. Fortunately for Ivan, Utkin II was an insightful man, and he demanded to hold custody over the prisoner while Lerrmontov considered his options. Unable to resist any longer, Lerrmontov agreed to release Ivan to the military. Unfortunately for Ivan, four of his workers were knifed to death by Lerrmontov's guards before Utkin's soldiers managed to remove them from the prison. When Lerrmontov refused to hand the guards over to Utkin for punishment, the general arrested Lerrmontov in a short skirmish which resulted in the death of Lerrmontov's personal bodyguard.

When Ivan Bunin finally made it back to Barcelona to resume construction, he found that Lerrmontov had maliciously sabotaged most of his work. Hundreds of miles of road were scarred by ploughs, tons of gravel were scattered across the countryside, all the horses and oxen were gone, and every piece of equipment had been sold or broken. The Trans-Crimean highway was ruined, and it would take years to get back to speed, if he could. Ivan wrote a pamphlet describing his story, and in its conclusion, he called for the dissolution of the Duchies and the replacement of Civil Service. Both institutions, he felt, were outmoded, and if they acted, could only do harm as they had to him.

The following year, 1582, was the year of the Russangxi response. Today, we call it the First Cultural Revolution, but at the time, it was a spontaneous gahtering of community. A solid identity, the identity built by Pobisk Kuznetsov, moved together and began underbidding Civil Service contracts. The loss of money was staggering--if anyone tried this level of boycott today, markets would collapse--but the message was clear. Civil Service would no longer be tolerated. Private companies would do the work at any price, because the government was no longer desired.

After nine months, the economic effect became crippling. Several of the provinces were suffering from massive deflation because the Russangxi's low wages were lowering prices. Ivan Bunin used this time to write and publish a series of political essays, the Bunin Letters. In these essays, he advocated three things:

1. The dissolution of the Duchies, the dissolution of Civil Service, and the creation of Provincial Judicial Districts.

2. The privatization of most public works.

3. The ratification of Zadornov's court amendments.

He called himself "A Russangxi Voice"--though he had no assigned authority--and the Russangxi revolutionaries seemed to accept him as their representative. In the last week of the Parliamentary session in 1582, Ivan met with Evgeny and discussed resolutions to the increasingly horrible condition of the economy. Things had reached such a low that in the day before the meeting, the Russian marketplace had been overrun by desperate farmers demanding an end to the crisis and the resumption of proper wages. Unless the Russangxi returned to work at the full cost of labor, the non-Russangxi farmers simply couldn't charge enough for the food to make a profit.

Evgeny talked with Tsar Kavkaz V and declared an official Constitutional Congress. Within a week, plans were set in motion to revoke all titles of Duke, disassemble the vestigial scraps of the Russian Civil Service, and implement the changes required by the Russangxi. Parliament rewrote the third section of the Liberal Letters to take into account "the new People." Money was budgeted to recompense Ivan for the damages caused by Lerrmontov, and the Russangxi people were asked to return to work at full wages.

The new third section of the Liberal Letters was named Bunin's Letter, and with its official signature into the Constitution, the First Cultural Revolution ended, and the Industrial Era began.

So far...

Whee. Finished this one late at night. :] That's it for the Renaissance. It's also the end of all the turns I've played so far, so my next update will include NEW TURNS and MORE STRATEGY and stuff like that.