Part 6: November 17 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be discussing the best bike paths in London. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the sixth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the state of Europe, a decade after the fall of France, and the impending clash between Spain and the United Provinces.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the sixth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed the state of Europe, a decade after the fall of France, and the impending clash between Spain and the United Provinces. By 1709, the Flemish spy Willem Ganesvoort, working as a double agent for the Dutch, had reported in to Madrid, and took note of a suspicious troop movement. Following them as a guide to the French countryside, he suspected the Spanish army straight up towards France from the south. Reporting covertly to the Dutch ministers, they were able to move the army of Christian van Waldeck, an army of a similar size and composition, south to meet them.

By 1709, the Flemish spy Willem Ganesvoort, working as a double agent for the Dutch, had reported in to Madrid, and took note of a suspicious troop movement. Following them as a guide to the French countryside, he suspected the Spanish army straight up towards France from the south. Reporting covertly to the Dutch ministers, they were able to move the army of Christian van Waldeck, an army of a similar size and composition, south to meet them.

Ganesvoort trailing the Spanish army.

Attempting to evade Waldeck, the Spanish headed north and east towards Marseilles. The Dutch army moving south, attempted to meet them around Lyou, but were delayed by dense terrain when the Spanish suddenly broke north west to Nantes, successfully getting around Waldeck.

Attempting to evade Waldeck, the Spanish headed north and east towards Marseilles. The Dutch army moving south, attempted to meet them around Lyou, but were delayed by dense terrain when the Spanish suddenly broke north west to Nantes, successfully getting around Waldeck.

Waldeck is caught in the forests as the Spanish evade their armies.

With the Dutch behind them, the Spanish needed to sprint their army as fast as possible to Paris, but the Dutch were unwilling to allow the Spanish free reign ransacking the countryside and evel less willing to risk Paris in a siege.

With the Dutch behind them, the Spanish needed to sprint their army as fast as possible to Paris, but the Dutch were unwilling to allow the Spanish free reign ransacking the countryside and evel less willing to risk Paris in a siege. To this end Ouwerkerk moved the Paris militia and the conscripts from the United Provinces directly south, meeting the Spanish just north of Bordeaux, which the battle was named after. The battle of Bordeaux was fought June 10th, 1710 after considerable time was spent pushing about the Dutch army into position. The Spanish, desperate for a breakthrough, attempted to meet the attack head on, while Ouwerkerk was satisfied moving his forces about in attempt to blockade and slow the Spanish, possibly until Waldeck would arrive. Finally moving to a breakthrough by 2:00 PM, the Spanish quickly positioned their cannons and prepared to advance.

To this end Ouwerkerk moved the Paris militia and the conscripts from the United Provinces directly south, meeting the Spanish just north of Bordeaux, which the battle was named after. The battle of Bordeaux was fought June 10th, 1710 after considerable time was spent pushing about the Dutch army into position. The Spanish, desperate for a breakthrough, attempted to meet the attack head on, while Ouwerkerk was satisfied moving his forces about in attempt to blockade and slow the Spanish, possibly until Waldeck would arrive. Finally moving to a breakthrough by 2:00 PM, the Spanish quickly positioned their cannons and prepared to advance.

Ouwerkerk casually waiting for the Spanish breakthrough.

The Dutch army was nearly twice the size of the Spanish army, many of whom were veterans of the Paris conquest and the Mustard rebellion. However, they were considerably worse in terms of quality and discipline, and many were press ganged from the French populace. It would not be unlikely that the army would break and flee if the Spanish managed to present stiff opposition.

The Dutch army was nearly twice the size of the Spanish army, many of whom were veterans of the Paris conquest and the Mustard rebellion. However, they were considerably worse in terms of quality and discipline, and many were press ganged from the French populace. It would not be unlikely that the army would break and flee if the Spanish managed to present stiff opposition.

Dutch troops were lined as far as the eye could see, but their numbers were their only advantage.

The Dutch had ended their deployment with a thick, 5 rank thick line across to accommodate their much weaker composition of infantry, and to prevent complete domination by cavalry. Center, and in the position to receive the greatest amount of fire were the Dutch conscripts. To their right were the Amsterdam militia, and their left the Paris militia. Each was organized into a section to act on specific orders (for example, Paris militia were used to flank, the conscripts were used to engage directly) Their far left flank was anchored by the pike militia, intended to ward away cavalry, while the right contained their regiments of horse, who would counter charge and tie down the Spanish cavalry until the flank could be secured with bayonets.

The Dutch had ended their deployment with a thick, 5 rank thick line across to accommodate their much weaker composition of infantry, and to prevent complete domination by cavalry. Center, and in the position to receive the greatest amount of fire were the Dutch conscripts. To their right were the Amsterdam militia, and their left the Paris militia. Each was organized into a section to act on specific orders (for example, Paris militia were used to flank, the conscripts were used to engage directly) Their far left flank was anchored by the pike militia, intended to ward away cavalry, while the right contained their regiments of horse, who would counter charge and tie down the Spanish cavalry until the flank could be secured with bayonets.

Militia were forced to use deep lines, wasting many guns to ward off cavalry charges.

The Spanish had anchored their left flank with 2 detachments of guns, though they were left relatively unguarded. Their remaining gun battery was deployed in their right flank attended by two regiments of horse. Their infantry was deployed in a long comparatively thin line, though the thicker Dutch line still stretched half again as far. Two more regiments of horse were left in reserve, one including Colonel Chaves, leader of the Spanish army.

The Spanish had anchored their left flank with 2 detachments of guns, though they were left relatively unguarded. Their remaining gun battery was deployed in their right flank attended by two regiments of horse. Their infantry was deployed in a long comparatively thin line, though the thicker Dutch line still stretched half again as far. Two more regiments of horse were left in reserve, one including Colonel Chaves, leader of the Spanish army.

Thin Spanish lines advancing on the Dutch. The thin formation wasted far fewer guns.

The Spanish, finding the Dutch flank overlapped their left, shifted their lines leaving their left flank cannons vulnerable. Using the woods as cover, the Dutch regiments of horse on the right flank sprinted forward to spike the Spanish demicannons. Emerging through the foliage, the Dutch horsemen managed to demolish the Spanish cannons before wheeling back around their own lines.

The Spanish, finding the Dutch flank overlapped their left, shifted their lines leaving their left flank cannons vulnerable. Using the woods as cover, the Dutch regiments of horse on the right flank sprinted forward to spike the Spanish demicannons. Emerging through the foliage, the Dutch horsemen managed to demolish the Spanish cannons before wheeling back around their own lines.

Dutch cavalry bursting forth from a small stand of trees, catching the immobile Spanish cannons off guard.

Meanwhile, the Spanish had straightened their lines, the remaining cannons, firing grape into the advancing Dutch managed to kill many of their assailants, but the Dutch advance pushed the center and right of their formation into the Spanish.

Meanwhile, the Spanish had straightened their lines, the remaining cannons, firing grape into the advancing Dutch managed to kill many of their assailants, but the Dutch advance pushed the center and right of their formation into the Spanish.

The central Spanish artillery battery exacts a terrible toll with their grapeshot, fired point blank.

On their right, the Spanish regiments of horse attempted to delay the massive Dutch left flank, moving across the Dutch flank to get behind the Paris militia. However, they were intercepted by the Dutch Pike militia, who were able to tie them down under the militia’s arc of fire. Quickly despatched, the Dutch left flank was able to swing around before the Spanish could engage the Dutch center.

On their right, the Spanish regiments of horse attempted to delay the massive Dutch left flank, moving across the Dutch flank to get behind the Paris militia. However, they were intercepted by the Dutch Pike militia, who were able to tie them down under the militia’s arc of fire. Quickly despatched, the Dutch left flank was able to swing around before the Spanish could engage the Dutch center.

The Dutch still used an ancient battalion of pike armed soldiers. Here they make a good showing against the Spanish cavalry.

Caught in a “v” formation, the Spanish forces began receiving tremendous amounts of fire from all sides. The Amsterdam militia had moved far North behind the Bordeaux villas, attempting to fully encircle the Spanish forces in a closed triangle.

Caught in a “v” formation, the Spanish forces began receiving tremendous amounts of fire from all sides. The Amsterdam militia had moved far North behind the Bordeaux villas, attempting to fully encircle the Spanish forces in a closed triangle.

The Dutch catch the Spanish forces in a wedge. Capping it off, they surrounded the Spanish forces in all sides with only 3 fronts.

Out of ammunition, and being destroyed by the Spanish grape shot, the Dutch conscripts were ordered forward en masse with their bayonettes, finally silencing the last battery of Spanish cannon. Joining them from the left, the exhausted Pikemen were ordered to charge the regiments of Spanish line.

Out of ammunition, and being destroyed by the Spanish grape shot, the Dutch conscripts were ordered forward en masse with their bayonettes, finally silencing the last battery of Spanish cannon. Joining them from the left, the exhausted Pikemen were ordered to charge the regiments of Spanish line.

Despite being flanked, pinned down and utterly outnumbered, the Spanish infantry put up a very brave showing.

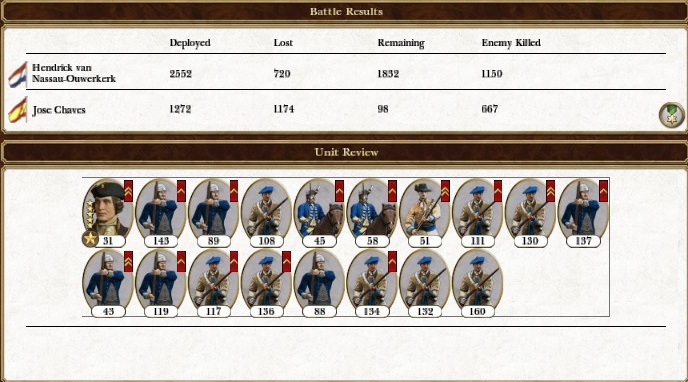

The Amsterdam militia, unable to fire into the Spanish safely, charged the Spanish from behind as well. Sandwiched between the militia and conscripts, the Spanish were quickly run down. The Spanish lost 1100 men, killed or captured, less than 100 of them escaped. Jose Chaves, colonel and leader of the Spanish army was killed during the ensuing melee leaving Lieutenant Coello in charge, who managed to retreat the remaining cavalry, dragging a demicannon behind.

The Amsterdam militia, unable to fire into the Spanish safely, charged the Spanish from behind as well. Sandwiched between the militia and conscripts, the Spanish were quickly run down. The Spanish lost 1100 men, killed or captured, less than 100 of them escaped. Jose Chaves, colonel and leader of the Spanish army was killed during the ensuing melee leaving Lieutenant Coello in charge, who managed to retreat the remaining cavalry, dragging a demicannon behind.

Casualty list for the battle of Bordeaux

Attempting to retreat to the Atlantic coast, hoping to evade the Dutch that surrounded them to the north and south, the fragments of the Spanish army were in dire straights. Ouwerkerk returned with the entire force of militia to Paris, sending the conscripts and regiments of horse in pursuit. They would assist Waldeck in pacifying and dominating Spain after they had destroyed the last remnants of the Spanish army.

Attempting to retreat to the Atlantic coast, hoping to evade the Dutch that surrounded them to the north and south, the fragments of the Spanish army were in dire straights. Ouwerkerk returned with the entire force of militia to Paris, sending the conscripts and regiments of horse in pursuit. They would assist Waldeck in pacifying and dominating Spain after they had destroyed the last remnants of the Spanish army.

After the main Battle of Bordeaux, the battle of Paris, and the later battle of Goa, the Dutch citizen soldier became a figure of reverence and a nationalistic icon in Dutch society.

The Spaniards, exhausted, were able to use their sole cannon to stop the Dutch cavalry from quickly running them down, and so the Dutch were forced to attack with infantry and cavalry. The Dutch conscripts caught up with them by June 21st, and were deployed for battle by early morning. Advancing with the intent of taking the Spanish gun, the Dutch moved briskly forward. Cannon fire from the single Spanish gun failed to make a significant impression on the infantry as they advanced, and so the Spanish cavalry was forced to engage and block.

The Spaniards, exhausted, were able to use their sole cannon to stop the Dutch cavalry from quickly running them down, and so the Dutch were forced to attack with infantry and cavalry. The Dutch conscripts caught up with them by June 21st, and were deployed for battle by early morning. Advancing with the intent of taking the Spanish gun, the Dutch moved briskly forward. Cannon fire from the single Spanish gun failed to make a significant impression on the infantry as they advanced, and so the Spanish cavalry was forced to engage and block. The Dutch, formed in thick blocks were not well trained enough to form squares. Instead, in thick block formations, the Dutch regiments had angled to form supporting fire towards each regiment in turn. The Spanish cavalry could engage the Dutch infantry in their flanks, but the group behind them was able to fire at the easy targets the cavalry presented, even as they did fight in melee. The few remaining cavalry, once they had been fired upon, were easy prey for a quick Dutch counter charge, which swarmed and eliminated the last of them.

The Dutch, formed in thick blocks were not well trained enough to form squares. Instead, in thick block formations, the Dutch regiments had angled to form supporting fire towards each regiment in turn. The Spanish cavalry could engage the Dutch infantry in their flanks, but the group behind them was able to fire at the easy targets the cavalry presented, even as they did fight in melee. The few remaining cavalry, once they had been fired upon, were easy prey for a quick Dutch counter charge, which swarmed and eliminated the last of them.

Dutch conscripts used covering arcs of fire, so any regiment that was charged by cavalry was under the firing arc of any other formation.

The Dutch cavalry, now with a free line into the Spanish, sprinted forward into the Spanish guns. Lieutenant Coello, now outnumbered nearly nine to one, just stood and watched as his artillery was demolished. He ordered his men to disperse, abandoning the army and officially ending the Spanish invasion of France. The end of this invasion was not the end of the fighting for the Dutch conscripts however. They would take part in counter invading Spain.

The Dutch cavalry, now with a free line into the Spanish, sprinted forward into the Spanish guns. Lieutenant Coello, now outnumbered nearly nine to one, just stood and watched as his artillery was demolished. He ordered his men to disperse, abandoning the army and officially ending the Spanish invasion of France. The end of this invasion was not the end of the fighting for the Dutch conscripts however. They would take part in counter invading Spain.

Coello watches his men die before throwing down his sword in despair.

Departing on ferries from Brest, the Dutch conscripts landed in the North coast near Bilbao, just as Waldeck managed to move across the pass to Spain from France by land. The counter attack had been planned for summer of 1711, hopefully before the Spanish could gain a new army.

Departing on ferries from Brest, the Dutch conscripts landed in the North coast near Bilbao, just as Waldeck managed to move across the pass to Spain from France by land. The counter attack had been planned for summer of 1711, hopefully before the Spanish could gain a new army. The Spanish had managed to raise something before the Dutch arrived. A small army of a few battalions of line. Knowing they would be unlikely to withstand the whole Dutch army, they instead moved their army North to attack the Dutch conscript force, hoping to kill them off, reverse course, then lift the impending siege at Madrid.

The Spanish had managed to raise something before the Dutch arrived. A small army of a few battalions of line. Knowing they would be unlikely to withstand the whole Dutch army, they instead moved their army North to attack the Dutch conscript force, hoping to kill them off, reverse course, then lift the impending siege at Madrid.

Spanish line intercept Dutch conscripts at Bilbao.

The skirmish of Bilbao, the large conscript force backed with Dutch regiments of horse against a smaller force of Spanish line was simply a repeat of the tactics in Bordeaux. Dutch infantry managed to gain the Spanish flank, pouring fire across the Spanish lines. A bayonette charge along with the outflanking cavalry managed to rapidly destroy the Spanish army. The Spanish lines were folded along their right flank, then smashed by cavalry and couldn't use their superior firepower (even though outnumbered) to defeat the Dutch.

The skirmish of Bilbao, the large conscript force backed with Dutch regiments of horse against a smaller force of Spanish line was simply a repeat of the tactics in Bordeaux. Dutch infantry managed to gain the Spanish flank, pouring fire across the Spanish lines. A bayonette charge along with the outflanking cavalry managed to rapidly destroy the Spanish army. The Spanish lines were folded along their right flank, then smashed by cavalry and couldn't use their superior firepower (even though outnumbered) to defeat the Dutch.

A Dutch wave of conscripts slams into the Spanish lines. Cavalry charged them from the rear in a coordinated assault.

Marching briskly down to Madrid on April 8th, 1711, Waldeck met up with the conscripts from the north and besieged Madrid, marching south towards the city with great speed. He fully intended to assault the city rather than wait it out.

Marching briskly down to Madrid on April 8th, 1711, Waldeck met up with the conscripts from the north and besieged Madrid, marching south towards the city with great speed. He fully intended to assault the city rather than wait it out.

Waldeck quickly reaches Madrid after combining the main force and the conscript garrison.

The old fortresses around Madrid, manned almost entirely by volunteers was scarcely in any condition to contest the city against the Dutch. A mere 1300 men arrayed against the more professional army of 1800 Dutch could only survive thanks to their fortifications. Marching to Buitrago del Lozoya, the Spanish could use that strong point to check a Dutch advance on the city itself.

The old fortresses around Madrid, manned almost entirely by volunteers was scarcely in any condition to contest the city against the Dutch. A mere 1300 men arrayed against the more professional army of 1800 Dutch could only survive thanks to their fortifications. Marching to Buitrago del Lozoya, the Spanish could use that strong point to check a Dutch advance on the city itself.

The ruined walls of Buitrago del Lozoya

Waldeck, confident that the new model Dutch army, armed with their new 12 pound foot artillery believed he could take this crumbling Spanish castle, and on November December 9th, he ordered his army forward.

Waldeck, confident that the new model Dutch army, armed with their new 12 pound foot artillery believed he could take this crumbling Spanish castle, and on November December 9th, he ordered his army forward. Wheeling his cannons forward, he was able to march far closer far faster than the Spanish had anticipated, setting up their cannon before the garrison could even properly man their own. The Dutch, playing things relatively safe, fired crippling volleys of cannon fire at the aging walls, while Spanish return fire could not match the range of the Dutch guns, and certainly not hit a target from those distances that were smaller than a castle wall.

Wheeling his cannons forward, he was able to march far closer far faster than the Spanish had anticipated, setting up their cannon before the garrison could even properly man their own. The Dutch, playing things relatively safe, fired crippling volleys of cannon fire at the aging walls, while Spanish return fire could not match the range of the Dutch guns, and certainly not hit a target from those distances that were smaller than a castle wall.

The Dutch assailed the castle walls from a distant hill. The castle's return cannon fire was beyond their effective range, while the Dutch cannons could scarcely miss such a large target.

The Spanish walls crumbled after several hours of battering, killing many of the men garrisoned along it. The Dutch, no longer under threat of fire from atop the city walls moved their men forward, along with their cannons.

The Spanish walls crumbled after several hours of battering, killing many of the men garrisoned along it. The Dutch, no longer under threat of fire from atop the city walls moved their men forward, along with their cannons.

The wall collapses.

Formed in dense formations along the left flank, and thin firing lines along the right and centre, the Dutch were wheeling their cannons forward so as to fire grape through the breach. The Spanish seeing this started to sally forth from the crumbling fortification in a direct frontal charge.

Formed in dense formations along the left flank, and thin firing lines along the right and centre, the Dutch were wheeling their cannons forward so as to fire grape through the breach. The Spanish seeing this started to sally forth from the crumbling fortification in a direct frontal charge.

The Dutch prepare for a Spanish counter attack as they prepare their cannons to fire grape into the breach.

The Dutch center and right held against the desperate Spanish charge, firing into the mob as they moved forward. The left flank however, crashed into the right flank of the compressed Spanish forces, routing their left and pushing their right flank into a massed mob, which rallied in the breach of the fortress.

The Dutch center and right held against the desperate Spanish charge, firing into the mob as they moved forward. The left flank however, crashed into the right flank of the compressed Spanish forces, routing their left and pushing their right flank into a massed mob, which rallied in the breach of the fortress.

The Dutch manage to outflank the Spanish as they sally forth from the breach.

A few hold outs managed to make a last stand along the right side breach of the castle, but all around, the Dutch army pressed in. Sweeping past the defense on the Spanish right, leaving two battalions to pin them down, a mass of Dutch troops swept through the Spanish fortress. The desperate melee on the left suddenly enveloped from behind, the remaining Spanish citizens for the most part threw down their arms, several of them pleading for their lives.

A few hold outs managed to make a last stand along the right side breach of the castle, but all around, the Dutch army pressed in. Sweeping past the defense on the Spanish right, leaving two battalions to pin them down, a mass of Dutch troops swept through the Spanish fortress. The desperate melee on the left suddenly enveloped from behind, the remaining Spanish citizens for the most part threw down their arms, several of them pleading for their lives.

The Spanish fight in a series of semi connected desperate last stands.

Victorious, the blue coated Dutch paraded into the city of Madrid, only to find empty coffers, and a country in financial disarray. Despite the massive size of it, Spain was granting less income than even the city of Amsterdam. The much anticipated overthrow of the Spanish Hapsburg oppressors revealed a tired, crumbling skeleton of their former glory.

Victorious, the blue coated Dutch paraded into the city of Madrid, only to find empty coffers, and a country in financial disarray. Despite the massive size of it, Spain was granting less income than even the city of Amsterdam. The much anticipated overthrow of the Spanish Hapsburg oppressors revealed a tired, crumbling skeleton of their former glory. In Amsterdam, it was played up as a glorious victory, much akin to David and Goliath, the Dutch republicans as heroes and champions of freedom over the Spanish monarchy, but the truth very much was that the Dutch trade juggernaut, and their massive population of French and colonial men to draw troops from could not have been stopped by anything the Spanish Hapsburgs had left to muster. With their richest trade partner, the French eliminated and her home ports block in their own territorial waters, nothing could have held back the Dutch by then.

In Amsterdam, it was played up as a glorious victory, much akin to David and Goliath, the Dutch republicans as heroes and champions of freedom over the Spanish monarchy, but the truth very much was that the Dutch trade juggernaut, and their massive population of French and colonial men to draw troops from could not have been stopped by anything the Spanish Hapsburgs had left to muster. With their richest trade partner, the French eliminated and her home ports block in their own territorial waters, nothing could have held back the Dutch by then. What’s more, Charles the Cursed of Spain, upon hearing the arrival of the Dutch upon his shores, had a fit of illness, and suffered what is suspected to have been a heart attack in February. Always in sickly health, and without an heir, the Dutch arrived in a Spain without a Hapsburg. Just before their conquest, a French prince, Phillip V, idle in the new French capitol in Strasburg had been made the first Bourbon King of Spain.

What’s more, Charles the Cursed of Spain, upon hearing the arrival of the Dutch upon his shores, had a fit of illness, and suffered what is suspected to have been a heart attack in February. Always in sickly health, and without an heir, the Dutch arrived in a Spain without a Hapsburg. Just before their conquest, a French prince, Phillip V, idle in the new French capitol in Strasburg had been made the first Bourbon King of Spain.

Phillip V, the first Bourbon monarch of a ruined Spain.

The French monarchy, now in a semblance of control over the crumbling Spanish nation immediately joined them in their war against the Dutch, hoping to use the armies and rebels from Spain, as well as the Spanish colonies in an attack back against the Dutch.

The French monarchy, now in a semblance of control over the crumbling Spanish nation immediately joined them in their war against the Dutch, hoping to use the armies and rebels from Spain, as well as the Spanish colonies in an attack back against the Dutch. In our next broadcast, we present the battle of Nancy, and the last breath of France. This has been episode 6 of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war.

In our next broadcast, we present the battle of Nancy, and the last breath of France. This has been episode 6 of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war.Next, we’re presenting the best bike paths of London for the autumn biking season. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.