Part 21: January 4 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we’ll be presenting a documentary on speculative fiction, and the inventions that followed. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-first part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed near all of the conquest of India.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-first part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last week, we discussed near all of the conquest of India. Dutch forces, many of them preparing themselves for the long trip back to Europe and to England, finally moved in to take out the last stronghold of the Maratha, but the Dutch command and government weren’t letting their guard down yet. And neither was the new 1740 republican cabinet. With India announced as conquered by the Dutch, miracles in America, which will be discussed later, and peace in Europe all ensured an easy sweep for the Republican party, even though they had retired to a new set of ministers under Arnold Van der Werff. An experienced cabinet of aged politicians, they had full knowledge of the situation their previous cabinet had been in.

Dutch forces, many of them preparing themselves for the long trip back to Europe and to England, finally moved in to take out the last stronghold of the Maratha, but the Dutch command and government weren’t letting their guard down yet. And neither was the new 1740 republican cabinet. With India announced as conquered by the Dutch, miracles in America, which will be discussed later, and peace in Europe all ensured an easy sweep for the Republican party, even though they had retired to a new set of ministers under Arnold Van der Werff. An experienced cabinet of aged politicians, they had full knowledge of the situation their previous cabinet had been in.

The cabinet in charge of the United Provinces as of 1740. They adopted the largest net tax profits of any cabinet to date.

With the tax income and net profits doubling since 1730, they had no intention of losing the advantages their predecessors had handed to them. This meant in part, that they did not invest in the army from the period of 1740 all the way up to 1745. The Dutch army evacuating from India would mean over five thousand troops would reinforce Europe. Instead of new armies, steam powered factories sprung up across Europe and India. These factory complexes could employ hundreds of Dutch, French, Spanish and Indian citizens, paying better wages than a farm hand could earn, and Dutch investment would be paid off in spades through tax revenue.

With the tax income and net profits doubling since 1730, they had no intention of losing the advantages their predecessors had handed to them. This meant in part, that they did not invest in the army from the period of 1740 all the way up to 1745. The Dutch army evacuating from India would mean over five thousand troops would reinforce Europe. Instead of new armies, steam powered factories sprung up across Europe and India. These factory complexes could employ hundreds of Dutch, French, Spanish and Indian citizens, paying better wages than a farm hand could earn, and Dutch investment would be paid off in spades through tax revenue.

Steam powered factories burned thousands of pounds of coal. Britain was the best source of coal, which meant the Dutch had to import their coal from all across their colonies, and from China.

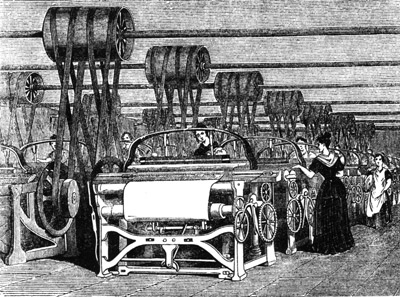

The first such factory built in the Den Haag had been the first practical application of the steam engine. Looms powered by steam were no longer dependent on the flow of water from rivers, and one could power far larger factories than before. Dutch looms churned out tons of cheap fabric, much of which was bought by the tens of millions of French.

The first such factory built in the Den Haag had been the first practical application of the steam engine. Looms powered by steam were no longer dependent on the flow of water from rivers, and one could power far larger factories than before. Dutch looms churned out tons of cheap fabric, much of which was bought by the tens of millions of French.

The steam powered factory of the 1700s could be built anywhere, their constant coal burning darkening the sky and buildings of the larger cities with soot and ash.

However, this meant the replenishment of forces in India had slowed. The infantry assumed this meant they were about to be recalled soon, but the reality was slightly different. The Dutch ministers assumed there would be another threat lurking behind the Maratha in India soon.

However, this meant the replenishment of forces in India had slowed. The infantry assumed this meant they were about to be recalled soon, but the reality was slightly different. The Dutch ministers assumed there would be another threat lurking behind the Maratha in India soon.

The Dutch, looking back behind them had made tremendous progress, and victory was in hand. However, it paid to remember that the Maratha were not the only Indian lords that had coveted their home nation.

The Dutch moved forward to attack Ahmedabad and Udaipur. The Maratha forces had been shattered in the Dutch push and had not consolidated back into Ahmedabad leaving it tremendously vulnerable. The Dutch assaulted the walls without hesitation. They were so eager that Crieckenbeeck, who had to file reports from his camp in Bombay, had been left behind by Colonel Hubertus Bulens. He had to gallop full tilt to the siege, and arrived after the troops had assaulted the walls.

The Dutch moved forward to attack Ahmedabad and Udaipur. The Maratha forces had been shattered in the Dutch push and had not consolidated back into Ahmedabad leaving it tremendously vulnerable. The Dutch assaulted the walls without hesitation. They were so eager that Crieckenbeeck, who had to file reports from his camp in Bombay, had been left behind by Colonel Hubertus Bulens. He had to gallop full tilt to the siege, and arrived after the troops had assaulted the walls.

Crieckenbeeck arrived a few hours after his army, making it just after the cannons had been prepared.

The Dutch marched straight forward, firing quicklime shells directly into the defenders and their fortifications, even as the Dutch infantry clamoured over the walls. The Maratha had nothing left to defend with, save sword and matchlock armed citizens, several of which were lined up on the wall. The Dutch forces simply overwhelmed them, overrunning position after position without slowing down.

The Dutch marched straight forward, firing quicklime shells directly into the defenders and their fortifications, even as the Dutch infantry clamoured over the walls. The Maratha had nothing left to defend with, save sword and matchlock armed citizens, several of which were lined up on the wall. The Dutch forces simply overwhelmed them, overrunning position after position without slowing down.

The walls were weakened and their morale diminished by shelling as the Dutch advanced making the assault more of a mop up than anything else.

The Maratha, desperate to stem the tide tried to reinforce the walls, and their breaches in the walls, but they couldn’t stop the Dutch advance. Whether it was on the walls or the through their breaches, the Dutch infantry pushed the Maratha back, running down everyone in their path. The Maratha tried to sally their cavalry forth and managed to destroy several cannon, but were too few in number to silence them all before reserve infantry drove them back. It was a classic case of too little too late.

The Maratha, desperate to stem the tide tried to reinforce the walls, and their breaches in the walls, but they couldn’t stop the Dutch advance. Whether it was on the walls or the through their breaches, the Dutch infantry pushed the Maratha back, running down everyone in their path. The Maratha tried to sally their cavalry forth and managed to destroy several cannon, but were too few in number to silence them all before reserve infantry drove them back. It was a classic case of too little too late.

The Dutch pushing through the sparse Maratha defenders through a breach in the wall. By now, the Maratha were too weak to stop them.

The Dutch having taken Ahmedabad, could now turn their attention to Udaipur. The forces in Udaipur hadn’t been destroyed by the advance of Crieckenbeeck and his forces in Bombay, leaving a large garrison to face the Dutch. However, unlike Ahmedabad, the city of Udaipur wasn’t fortified, making the battle an open field offensive. The Dutch opted to move forward in a dense fog early in the morning.

The Dutch having taken Ahmedabad, could now turn their attention to Udaipur. The forces in Udaipur hadn’t been destroyed by the advance of Crieckenbeeck and his forces in Bombay, leaving a large garrison to face the Dutch. However, unlike Ahmedabad, the city of Udaipur wasn’t fortified, making the battle an open field offensive. The Dutch opted to move forward in a dense fog early in the morning.

Dutch artillery moving through a dense fog in the suburbs of Udaipur. Target spotting, rudimentary as they already were, took a dramatic dive in accuracy.

Moving in and around the buildings around the suburbs, the Dutch managed to set their artillery up covered by buildings, the alleys and roads leading to them guarded by blocks of infantry. Quicklime shells rained down through the fog, hissing in the wet air. Maratha forces, scarcely made out through the dense air, were eventually hit by the Dutch lines as they advanced, often at point blank. The tremendous numbers of Dutch sweeping across the field making contact with the Maratha simply swept them aside. A battalion was lost in the fog, crushed by Maratha cavalry as determined later when the fog lifted, but otherwise, the Dutch simply marched over the Maratha forces.

Moving in and around the buildings around the suburbs, the Dutch managed to set their artillery up covered by buildings, the alleys and roads leading to them guarded by blocks of infantry. Quicklime shells rained down through the fog, hissing in the wet air. Maratha forces, scarcely made out through the dense air, were eventually hit by the Dutch lines as they advanced, often at point blank. The tremendous numbers of Dutch sweeping across the field making contact with the Maratha simply swept them aside. A battalion was lost in the fog, crushed by Maratha cavalry as determined later when the fog lifted, but otherwise, the Dutch simply marched over the Maratha forces.

Maratha cavalry in the fog appeared as though ghosts in the dark. They ran down the seventy third militia before running into too stiff resistance. Unable to organize a safe route of retreat in the murk, the offending cavalry were all found killed when the fog lifted.

It was 1740, the Dutch had finally eliminated the Maratha. The troops would have to remain for two to three years to stabilize their possessions, but the majority of the soldiers celebrated that milestone victory. However, when the Dutch had just prepared to ship back to Europe, the men were called back into action just months after their victory celebrations.

It was 1740, the Dutch had finally eliminated the Maratha. The troops would have to remain for two to three years to stabilize their possessions, but the majority of the soldiers celebrated that milestone victory. However, when the Dutch had just prepared to ship back to Europe, the men were called back into action just months after their victory celebrations.

BBC's very own Sue Perkins at a recreation of a 1700s celebration. Gluttony, inebriation and jollity were the words of the day, taken to an extreme that modern men would find enviable and frightening.

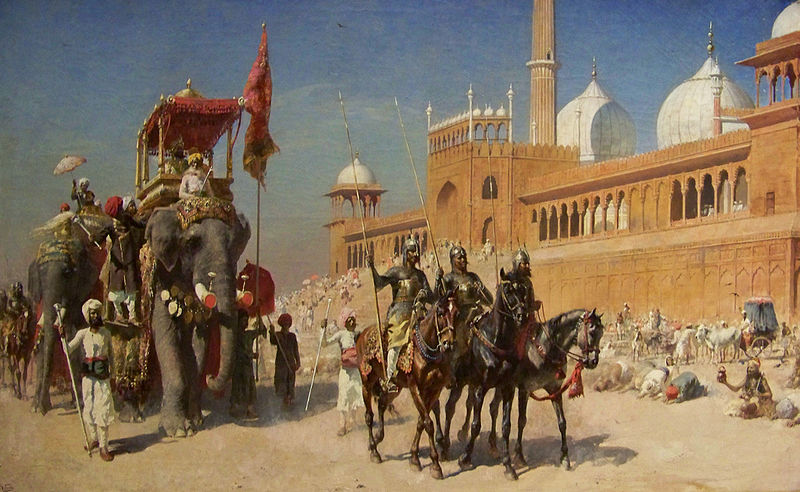

The Mughal, the former rulers of the Indian subcontinent, seeing the Maratha eradicated without having to lift a finger believed the continent was their birthright. Now with the Maratha out of the way, they tried to reclaim it, but were denied by the Dutch. Enraged, they moved to attack the Dutch in the north of India, hoping to quickly reclaim the continent by force.

The Mughal, the former rulers of the Indian subcontinent, seeing the Maratha eradicated without having to lift a finger believed the continent was their birthright. Now with the Maratha out of the way, they tried to reclaim it, but were denied by the Dutch. Enraged, they moved to attack the Dutch in the north of India, hoping to quickly reclaim the continent by force.

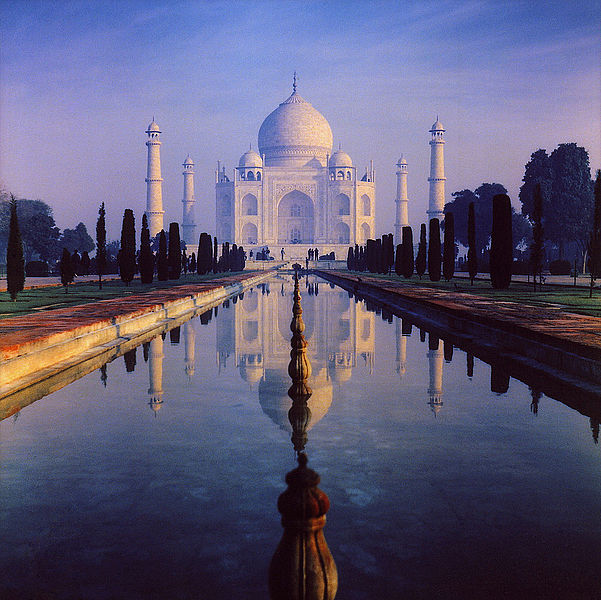

A symbol of Mughal power, the Taj Mahal was meant to project their Empire's power and invincibility. They were far from the days of the construction of that powerful monument.

It was not clever administration that had led to the downfall of the Mughal empire thirty years prior against the fledgling Maratha. This decision was no wiser. The Dutch forces now excited at the prospect of returning home, immediately moved out across all fronts, leaving the bare minimum across their holdings to prevent the Maratha from rebelling. Dutch forces managed to encircle Lahore and Srinagar without encountering much resistance, and Crieckenbeeck tore through Mughal forces that had moved to attack the Dutch before moving to Neroon Kot.

It was not clever administration that had led to the downfall of the Mughal empire thirty years prior against the fledgling Maratha. This decision was no wiser. The Dutch forces now excited at the prospect of returning home, immediately moved out across all fronts, leaving the bare minimum across their holdings to prevent the Maratha from rebelling. Dutch forces managed to encircle Lahore and Srinagar without encountering much resistance, and Crieckenbeeck tore through Mughal forces that had moved to attack the Dutch before moving to Neroon Kot.

The Mughal army was considered outright antiquated by the Dutch and even the former Maratha. Relying on medieval armies, weapons and tactics, their decision to go to war was foolish, the product of a delusional Emperor, Ahmad Shah Bahadur.

Mughal forces crossed the Indus river late in 1741. These had outdated compared to the Maratha, and perhaps even the forces of Mysore. Their army was almost entirely swordsmen, dervishes and pikemen. Lacking guns, they massed against the Dutch and performed suicidal full frontal charges. Rushing forward towards the Dutch, many of them were gunned down far before their realm of expertise could be exercised. The Dutch V.O.C., more than able to fight in melee pushed them back, destroying the advancing Mughal forces.

Mughal forces crossed the Indus river late in 1741. These had outdated compared to the Maratha, and perhaps even the forces of Mysore. Their army was almost entirely swordsmen, dervishes and pikemen. Lacking guns, they massed against the Dutch and performed suicidal full frontal charges. Rushing forward towards the Dutch, many of them were gunned down far before their realm of expertise could be exercised. The Dutch V.O.C., more than able to fight in melee pushed them back, destroying the advancing Mughal forces.

The Dutch lined against the Mughal. The Mughal had to charge forward into melee as quickly as possible.

The Dutch veterans, conquerors of the Maratha were quickly dispatching the far inferior Mughal forces. Pushing north towards the Indus river without delay, the Dutch were preparing to secure the remainder of India. The war with the Mughal would be over within a year.

The Dutch veterans, conquerors of the Maratha were quickly dispatching the far inferior Mughal forces. Pushing north towards the Indus river without delay, the Dutch were preparing to secure the remainder of India. The war with the Mughal would be over within a year.

The rain clears and the sun starts to appear as the Mughal assault is broken and driven back north of the Indus.

Approaching Neroon Kot across the Indus river, the Dutch forces met the Mughal forces attempting to prevent a river crossing. The battle in the rain and fog saw the Dutch pouring cannon fire and quicklime shells over the Mughal forces, covering an advance. The Dutch saw the Mughal attempting to make a crossing on the bridge to their left, but kept those in check with their reserve. Unable to remain under fire to wait for a Dutch advance, nor willing to back away from the crossing to allow a Dutch advance, the Dutch had forced the Mughal Empire to cross the narrow river crossing.

Approaching Neroon Kot across the Indus river, the Dutch forces met the Mughal forces attempting to prevent a river crossing. The battle in the rain and fog saw the Dutch pouring cannon fire and quicklime shells over the Mughal forces, covering an advance. The Dutch saw the Mughal attempting to make a crossing on the bridge to their left, but kept those in check with their reserve. Unable to remain under fire to wait for a Dutch advance, nor willing to back away from the crossing to allow a Dutch advance, the Dutch had forced the Mughal Empire to cross the narrow river crossing.

The Dutch fight the disparate Mughal forces along a river crossing.

The narrow river pass, well ranged in by the Dutch was a mass of bullets and shells. Choked with corpses, the Indus river crossing, which had included Mughal forces that were nominally meant to protect the towns, villages, cities and fortifications on the North of the river crossing saw Dutch forces advance into the Sindh region, capturing it without further opposition.

The narrow river pass, well ranged in by the Dutch was a mass of bullets and shells. Choked with corpses, the Indus river crossing, which had included Mughal forces that were nominally meant to protect the towns, villages, cities and fortifications on the North of the river crossing saw Dutch forces advance into the Sindh region, capturing it without further opposition.

Dutch forces could hardly miss the oncoming Mughal soldiers if they had tried. The Mughal forces were completely massacred.

Now, the armies that had swept from East to west during the last push against the Maratha had nothing left but to sack Lahore. Dutch soldiers completely swept over the city walls of the last outpost of the former great nation. Unable to adapt, the Mughal Empire, which had ruled the Indian sub continent since 1526 had fallen entirely. Dutch troops simply swarmed over the walls, their men superior in training, armaments, discipline and numbers, the Mughal could not even stop the Dutch from taking the walls directly.

Now, the armies that had swept from East to west during the last push against the Maratha had nothing left but to sack Lahore. Dutch soldiers completely swept over the city walls of the last outpost of the former great nation. Unable to adapt, the Mughal Empire, which had ruled the Indian sub continent since 1526 had fallen entirely. Dutch troops simply swarmed over the walls, their men superior in training, armaments, discipline and numbers, the Mughal could not even stop the Dutch from taking the walls directly.

1700s Dutch painters taking a cue from Rembrandt use light to portray the conquering Dutch forces as radiant warriors.

Unlike the great European nations under Dutch rule, the Mughal and Maratha countries were taken as new Dutch provinces without the same rights as the member states of the Western Atlantic Federation. Unlike France, which remained in name and nationalism, members of India were encouraged to live, act, eat and work as though they were Dutch. Dutch schools had become the norm over the past decade, and it was becoming clear that India, formerly a diverse nation of many cultures, was becoming more and more homogenously Dutch. Even their myriad religions were being replaced by Protestant teachings from the dozens of churches and schools.

Unlike the great European nations under Dutch rule, the Mughal and Maratha countries were taken as new Dutch provinces without the same rights as the member states of the Western Atlantic Federation. Unlike France, which remained in name and nationalism, members of India were encouraged to live, act, eat and work as though they were Dutch. Dutch schools had become the norm over the past decade, and it was becoming clear that India, formerly a diverse nation of many cultures, was becoming more and more homogenously Dutch. Even their myriad religions were being replaced by Protestant teachings from the dozens of churches and schools.

The Dutch government promoted Christianity in India, as cultural unhappiness and unrest was greater in India than it was in Catholic held regions. The change in religion caused outrage for a short period, but with the strong garrisons present before they were to be shipped out, the country was held in check until a generation had been brought around to Christian thinking.

India had been a religiously diverse nation, with Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus and Islams. Since 1720, Christianity had spread along with other Dutch teachings. Though not inclined towards the same sort of preaching as other Christian nations, the Dutch were having difficulties in controlling the religious populace of India, many of whom were unwilling to cooperate with the clashing culture of the conquering Dutch. Forced to burn down temples and spread Christianity to many nations in India to gradually acclimatize the Indian populace to Dutch culture and community values, the United Provinces were having almost as much difficulty in dealing with religious unrest as they were with Indian nationalists.

India had been a religiously diverse nation, with Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus and Islams. Since 1720, Christianity had spread along with other Dutch teachings. Though not inclined towards the same sort of preaching as other Christian nations, the Dutch were having difficulties in controlling the religious populace of India, many of whom were unwilling to cooperate with the clashing culture of the conquering Dutch. Forced to burn down temples and spread Christianity to many nations in India to gradually acclimatize the Indian populace to Dutch culture and community values, the United Provinces were having almost as much difficulty in dealing with religious unrest as they were with Indian nationalists.

India was a nation of many cultures and religions. Unable to accomodate for them, the confused Europeans did not administer the nation with the same tact or skill the Maratha or Mughal had. Instead, they homogenized the region.

However, the costs of policing and converting the population was well worth it. Indian factories were being expanded in the many wealthy towns and cities, and the Dutch were raking in tens of millions of guilders every year in tax revenue. With an annual tax take of thirty-seven-million guilders per year, the Indian sub continent was earning nearly as much as the Dutch were capable of earning in their European territories. With new steam powered factories built much like the one in Den Haag rolling into production across India, it would not be long until their most prosperous cities were just as great as the European industrial centers around France and Germany.

However, the costs of policing and converting the population was well worth it. Indian factories were being expanded in the many wealthy towns and cities, and the Dutch were raking in tens of millions of guilders every year in tax revenue. With an annual tax take of thirty-seven-million guilders per year, the Indian sub continent was earning nearly as much as the Dutch were capable of earning in their European territories. With new steam powered factories built much like the one in Den Haag rolling into production across India, it would not be long until their most prosperous cities were just as great as the European industrial centers around France and Germany. Now, the only remaining force beyond the Dutch in India were the Persians in Afghanistan. Far to the North and too weak to attempt the same aggressive attack as the Mughal, the Dutch were not afraid of the Persians. Instead, the Dutch by 1745, had finally earned enough of a respite to move their forces away and back to England. Loading into transports in the Indian Ocean, the Dutch were now prepared to finally end the war.

Now, the only remaining force beyond the Dutch in India were the Persians in Afghanistan. Far to the North and too weak to attempt the same aggressive attack as the Mughal, the Dutch were not afraid of the Persians. Instead, the Dutch by 1745, had finally earned enough of a respite to move their forces away and back to England. Loading into transports in the Indian Ocean, the Dutch were now prepared to finally end the war. The French had been beaten, the Spanish had been beaten, the Austrians had been beaten and the Maratha had been beaten. All at the hand of the tiny Dutch trade nation that had 40 years prior, been one of the least significant European nations in the world. Only Britain, protected by a narrow strip of ocean, and by fortuitous circumstances well beyond Dutch control could survive against them, and after 20 years of war without fighting, excluding the war in the Americas, the Dutch had finally set their eyes on letting peace reign. Surely without the British menacing the Dutch west, the Poles would have no interest whatsoever in declaring war, and without Polish backing neither would the Italian states. The end was in sight, so long as the Dutch could defeat Britain before Poland, Sweden or Russia could enter the war.

The French had been beaten, the Spanish had been beaten, the Austrians had been beaten and the Maratha had been beaten. All at the hand of the tiny Dutch trade nation that had 40 years prior, been one of the least significant European nations in the world. Only Britain, protected by a narrow strip of ocean, and by fortuitous circumstances well beyond Dutch control could survive against them, and after 20 years of war without fighting, excluding the war in the Americas, the Dutch had finally set their eyes on letting peace reign. Surely without the British menacing the Dutch west, the Poles would have no interest whatsoever in declaring war, and without Polish backing neither would the Italian states. The end was in sight, so long as the Dutch could defeat Britain before Poland, Sweden or Russia could enter the war.

The Dutch were most greatly threatened by the Polish.

Though by 1744 a strange diplomatic token was granted by the Russians implying war between them would be unlikely. Exchanging the technology for the steam driven pump designed to empty mines and quarries of ground water, the Dutch were given the region of Astrakhan in the far south east of Russia. Though the Russians clearly could conquer the region at any time they wanted, the Dutch were considering this gesture as a positive one. Hope and positivity for the end of a two decade long war was rampant across the United Provinces. Men from across Europe boasted that the English would be out of the war within five years once the army from India returned.

Though by 1744 a strange diplomatic token was granted by the Russians implying war between them would be unlikely. Exchanging the technology for the steam driven pump designed to empty mines and quarries of ground water, the Dutch were given the region of Astrakhan in the far south east of Russia. Though the Russians clearly could conquer the region at any time they wanted, the Dutch were considering this gesture as a positive one. Hope and positivity for the end of a two decade long war was rampant across the United Provinces. Men from across Europe boasted that the English would be out of the war within five years once the army from India returned.

The Russians sell Astrakhan to the Dutch in exchange for a steam pump patent.

All through that period of optimism, the Dutch in America didn’t have the same luxury. With British forces concentrated strongly across their southern border, the Dutch would have a difficult time holding on for five more years waiting for the support of the colonies from Britain to end. Having held their territory, and consolidating their position into a strong defensive point, the Dutch government had considered America a lesser priority compared to preparing for war in Europe.

All through that period of optimism, the Dutch in America didn’t have the same luxury. With British forces concentrated strongly across their southern border, the Dutch would have a difficult time holding on for five more years waiting for the support of the colonies from Britain to end. Having held their territory, and consolidating their position into a strong defensive point, the Dutch government had considered America a lesser priority compared to preparing for war in Europe.

Britain was fairly well dug in, with armies stretching up all across the coast.

The British however, would not wait. Nor would the Dutch minister of the Americas Rodolf Geiden and his generals. Watching and waiting for any opportunity or mistake, the Dutch of the Americas prepared their forces, scraped what few native auxiliaries they could not afford together, and prepared to advance.

The British however, would not wait. Nor would the Dutch minister of the Americas Rodolf Geiden and his generals. Watching and waiting for any opportunity or mistake, the Dutch of the Americas prepared their forces, scraped what few native auxiliaries they could not afford together, and prepared to advance.

The British still held much of North America, but a few key actions in the North near Quebec would provide a tremendous alteration to the course of the war in the Americas.

Karel Vrooman, the general of the Americas who had proven himself adequate taking over the islands around the east coast had truly proven himself when he was forced to defend against the British during their surprising sea borne assault at St. Augustine. By the time they had been repulsed and the Dutch had advanced well north, destroying both the Cherokee and Iroquois natives around the region, and pushing the British north of Philedelphia, Vrooman was by then a confident and on the rise general. Though not a strategic genius like Ouwerkerk or Waaldeck had been, nor the heroic figure Crieckenbeeck had proven to be, Vrooman had advanced quickly and efficiently, delegating much of his work to his junior generals.

Karel Vrooman, the general of the Americas who had proven himself adequate taking over the islands around the east coast had truly proven himself when he was forced to defend against the British during their surprising sea borne assault at St. Augustine. By the time they had been repulsed and the Dutch had advanced well north, destroying both the Cherokee and Iroquois natives around the region, and pushing the British north of Philedelphia, Vrooman was by then a confident and on the rise general. Though not a strategic genius like Ouwerkerk or Waaldeck had been, nor the heroic figure Crieckenbeeck had proven to be, Vrooman had advanced quickly and efficiently, delegating much of his work to his junior generals. Next broadcast, we move from India to North America. With tremendous financial power abroad, the ministers and generals of America wish to demolish British support abroad, while the Dutch ministers of Europe hope to smash aside British resistance directly in their own front door step.

Next broadcast, we move from India to North America. With tremendous financial power abroad, the ministers and generals of America wish to demolish British support abroad, while the Dutch ministers of Europe hope to smash aside British resistance directly in their own front door step. Next we will be discussing speculative fiction, looking at the books of tomorrow and a new year. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be discussing speculative fiction, looking at the books of tomorrow and a new year. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.