Part 29: January 28 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, we will be presenting a documentary on the culinary history of Great Britain, and what went wrong. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-ninth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the intense naval exchanges occurring in the English Channel.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the twenty-ninth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the intense naval exchanges occurring in the English Channel. Only one more battle would occur before the election. The Republican party had been riding on an all time high through their consistent victories, and the victories at sea fending off the English channel were a major part of their political campaign. However, they had not conquered as they had promised. The Dutch army which had been deflected from England, their new enemies in Poland and the increasing threat of the British army all conspired against them, a fact that the Orange party rallied behind. The Orange party being the more militant told the voting populace that as conquerors in days past, they argued that would be the best choice in the upcoming campaign, and that only they could take Britain.

Only one more battle would occur before the election. The Republican party had been riding on an all time high through their consistent victories, and the victories at sea fending off the English channel were a major part of their political campaign. However, they had not conquered as they had promised. The Dutch army which had been deflected from England, their new enemies in Poland and the increasing threat of the British army all conspired against them, a fact that the Orange party rallied behind. The Orange party being the more militant told the voting populace that as conquerors in days past, they argued that would be the best choice in the upcoming campaign, and that only they could take Britain.

William the Third during the glorious revolution. He attacked Britain to relieve King Charles, who was catholic.

This wasn’t an entirely false promise. It was the Orange faction that had invaded Britain before, and the Orange party was now using their own funds to reform the Blue Guard as the presidential and parliamentary guard. These were the Dutch political guard regiment which had accompanied William the third in his attack against England in the 17th century. Formed into the presidential guard after the war, the Blue Guard was formed out of the best troops Amsterdam had to offer, taking their best sergeants and veterans from across their empire. Regardless of who would win the election, these men would spearhead the assault.

This wasn’t an entirely false promise. It was the Orange faction that had invaded Britain before, and the Orange party was now using their own funds to reform the Blue Guard as the presidential and parliamentary guard. These were the Dutch political guard regiment which had accompanied William the third in his attack against England in the 17th century. Formed into the presidential guard after the war, the Blue Guard was formed out of the best troops Amsterdam had to offer, taking their best sergeants and veterans from across their empire. Regardless of who would win the election, these men would spearhead the assault.

The Dutch blue guard were a battalion that had taken part in the Dutch invasion of England. They were reduced during the death of William the Third, and eliminated completely after Ouwerkerk died. Guard battalions such as those cost far more to maintain, and so they were cut to save money. They were brought back in 1749 as a symbol of the return to England.

The Dutch Republican party had to scale back on their promises, stating that their wealth, their grand navy and their slow push over Europe would eventually see them grind the British down to nothing, and that their command of the world over would strangle their trade and economy eventually. This was because they knew the Dutch were no longer in any position to attack across the channel. It would have to wait on factors slightly beyond their control, mostly whether or not they could acquire a peace agreement between themselves and the Polish.

The Dutch Republican party had to scale back on their promises, stating that their wealth, their grand navy and their slow push over Europe would eventually see them grind the British down to nothing, and that their command of the world over would strangle their trade and economy eventually. This was because they knew the Dutch were no longer in any position to attack across the channel. It would have to wait on factors slightly beyond their control, mostly whether or not they could acquire a peace agreement between themselves and the Polish.

The war between the Dutch and English was intensifying year by year, not diminishing.

They did quietly work on their politics however. While there was the continued siege of the Venetians in Bosnia, and while the siege persisted for nearly two years, the Dutch government did not play up the military aspect of it. While unpopular at home, the Dutch wanted to project the image of a benign, benevolent nation which was not the power hungry expansionists that they had been in years prior. To make the Venetians surrender however, their army would need to be beaten.

They did quietly work on their politics however. While there was the continued siege of the Venetians in Bosnia, and while the siege persisted for nearly two years, the Dutch government did not play up the military aspect of it. While unpopular at home, the Dutch wanted to project the image of a benign, benevolent nation which was not the power hungry expansionists that they had been in years prior. To make the Venetians surrender however, their army would need to be beaten.

The Dutch surrounding Sarajevo.

The Dutch army had once again entrenched their forces outside the Venetian barracks, and had continually attempted to open negotiations with them, but to no avail. The Venetian force was nearly as large as the Dutch force assailing them, but were much more reliant on conscripts and poorly armed peasants. These were a common feature in battles defending one’s city where the local populace, desperate to fend off the foreign invaders would find what arms they could and join the army without any training, and often with poor equipment.

The Dutch army had once again entrenched their forces outside the Venetian barracks, and had continually attempted to open negotiations with them, but to no avail. The Venetian force was nearly as large as the Dutch force assailing them, but were much more reliant on conscripts and poorly armed peasants. These were a common feature in battles defending one’s city where the local populace, desperate to fend off the foreign invaders would find what arms they could and join the army without any training, and often with poor equipment.

The Dutch counter fortifications around Sarajevo in Bosnia.

The Dutch forces had set up on a hill which lead to a tall plateau on their right flank. To flank on that side, the Venetian forces would have to spend considerable time and energy climbing up the hill. With multiple battalions of militia held in reserve, the Dutch would have plenty of time to counter such a manoeuvre. These infantry were kept somewhat behind the main lines to cover the Venetian advance wherever they would move.

The Dutch forces had set up on a hill which lead to a tall plateau on their right flank. To flank on that side, the Venetian forces would have to spend considerable time and energy climbing up the hill. With multiple battalions of militia held in reserve, the Dutch would have plenty of time to counter such a manoeuvre. These infantry were kept somewhat behind the main lines to cover the Venetian advance wherever they would move.

A mass of militia held back in reserve columns.

The left was similarly backed by a second line of reserves. These Dutch infantry could extend the line out further, but as they did not have the luxury of a hill to defend, the Dutch decided to use their line infantry on the left rather than more weak militia. With reserves to move either to the flanks, or to facilitate a breakthrough charge in the center, the Dutch line was mostly unassailable. Fortified in the center, and capable of overwhelming a melee assault through their reserves, the Dutch were forcing the Venetians into an attempt at flanking.

The left was similarly backed by a second line of reserves. These Dutch infantry could extend the line out further, but as they did not have the luxury of a hill to defend, the Dutch decided to use their line infantry on the left rather than more weak militia. With reserves to move either to the flanks, or to facilitate a breakthrough charge in the center, the Dutch line was mostly unassailable. Fortified in the center, and capable of overwhelming a melee assault through their reserves, the Dutch were forcing the Venetians into an attempt at flanking.

The Dutch right could sweep up the hill to counter a flanking manoeuvre. The militia took the high ground on that side, whereas it was fairly flat on the left.

The reserves moving out to the flanks to cover the venetian assault lacked the fortifications that their center had. The mass volume of militia moving to the right were able to force back and move down the hill towards the Venetian center. Pushed out of position by the Venetian retreat on the right, the Dutch militia were given a hard fight by the outnumbered Venetian regulars, but eventually forced them out of the fight. In the center, the Dutch and their earthworks were able to trade shots with the Italian force, killing hundreds of the advancing infantry in mass volleys.

The reserves moving out to the flanks to cover the venetian assault lacked the fortifications that their center had. The mass volume of militia moving to the right were able to force back and move down the hill towards the Venetian center. Pushed out of position by the Venetian retreat on the right, the Dutch militia were given a hard fight by the outnumbered Venetian regulars, but eventually forced them out of the fight. In the center, the Dutch and their earthworks were able to trade shots with the Italian force, killing hundreds of the advancing infantry in mass volleys.

Venetian infantry managed to line up below the Dutch, but couldn't get a clear shot against them.

On the left, the Dutch were in a position opposite of their right flank. The Dutch deployed their reserve regular infantry and were opposed the armed citizenry on the Venetian right. The Venetian right flank was far more numerous than the left flank. Unlike the fight which broke out on the Dutch right flank however, Dutch forces on the left were on nearly even numbers to the firelock armed citizens attacking their left. Grenadiers managed to break through their opposition with a volley of explosives followed by a charge. The hole they created in the right flank of the Venetian line saw the rapid and complete collapse of the army. With the Dutch militia moving down their left flank and the Dutch regulars pushing back their right, the Venetian army was forced to call a general retreat.

On the left, the Dutch were in a position opposite of their right flank. The Dutch deployed their reserve regular infantry and were opposed the armed citizenry on the Venetian right. The Venetian right flank was far more numerous than the left flank. Unlike the fight which broke out on the Dutch right flank however, Dutch forces on the left were on nearly even numbers to the firelock armed citizens attacking their left. Grenadiers managed to break through their opposition with a volley of explosives followed by a charge. The hole they created in the right flank of the Venetian line saw the rapid and complete collapse of the army. With the Dutch militia moving down their left flank and the Dutch regulars pushing back their right, the Venetian army was forced to call a general retreat.

Dutch grenadiers punch through the Venetian lines. The Dutch flooded through the gap, pushing back the Venetian army back into their bunker.

Forced back into their barracks, the Venetians were brought once more to the diplomacy table by the Dutch. Now outnumbered ten to one, lacking fortifications, allies or any additional forces abroad, the Dutch were able to force the Venetian governor into signing peace under very strict terms. The Dutch would receive a monthly fee from the Venetian government, would receive permanent trade rights, and would hold the right to move their armies through their territory. In return, the Venetians had the “benefit” of the Croatian Dutch army protecting them. Just as much their protectors, the Dutch were there to enforce the agreement between them.

Forced back into their barracks, the Venetians were brought once more to the diplomacy table by the Dutch. Now outnumbered ten to one, lacking fortifications, allies or any additional forces abroad, the Dutch were able to force the Venetian governor into signing peace under very strict terms. The Dutch would receive a monthly fee from the Venetian government, would receive permanent trade rights, and would hold the right to move their armies through their territory. In return, the Venetians had the “benefit” of the Croatian Dutch army protecting them. Just as much their protectors, the Dutch were there to enforce the agreement between them.

The Dutch victory over the Venetians. After the battle, the Dutch outnumbered the Venetian forces nearly ten to one. Their own forces were fairly intact.

This was the last offensive before the Dutch election. More important than the support gained from the Dutch populace, their conduct in Bosnia helped somewhat with foreign relations. The Polish were still too powerful to convince, and the Dutch economic heartlands were likely too tempting, leaving them in a continual state of war. If the Dutch could shatter the main forces, especially if the Polish attacked, it was very likely they could talk their way out of prolonging the war. On the other hand, their Prussian allies were pressing for more offensive actions around Poland.

This was the last offensive before the Dutch election. More important than the support gained from the Dutch populace, their conduct in Bosnia helped somewhat with foreign relations. The Polish were still too powerful to convince, and the Dutch economic heartlands were likely too tempting, leaving them in a continual state of war. If the Dutch could shatter the main forces, especially if the Polish attacked, it was very likely they could talk their way out of prolonging the war. On the other hand, their Prussian allies were pressing for more offensive actions around Poland.

The Polish and the Prussians had a very long adversarial relationship. Even as far back as the old Teutonic order of knights who were beaten at Grunwald, marking the ascension of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The election was fairly close run. The Republicans managed a close victory through their improvements to prosperity and the re-opening of many of the trade routes that had been lost to war. Doing so managed to gain their party the support of the fledgling V.O.C. political party making it the first minority government in the world. Led by Statholder Joren Friso, the new ministers were fairly middling, save for their incredibly competent Justice Minister, Petrus Schouman. A German born, Dutch judge who worked in India, Schouman was brought into politics for his broad knowledge of multi-regional law and politics. A necessity as more and more cultures were brought into the fold of the Dutch Empire, but also because his expertise of law was needed when negotiating the heavily Dutch favoured treaties with the Dutch protectorates.

The election was fairly close run. The Republicans managed a close victory through their improvements to prosperity and the re-opening of many of the trade routes that had been lost to war. Doing so managed to gain their party the support of the fledgling V.O.C. political party making it the first minority government in the world. Led by Statholder Joren Friso, the new ministers were fairly middling, save for their incredibly competent Justice Minister, Petrus Schouman. A German born, Dutch judge who worked in India, Schouman was brought into politics for his broad knowledge of multi-regional law and politics. A necessity as more and more cultures were brought into the fold of the Dutch Empire, but also because his expertise of law was needed when negotiating the heavily Dutch favoured treaties with the Dutch protectorates.

Joren Friso. As Statholder, it was nominally his responsibility to lead the country during war time. A competent tacticion, Friso was not entirely prepared for the sheer scale of the military he now lead. Vrooman ended up taking a considerable number of his responsibilities.

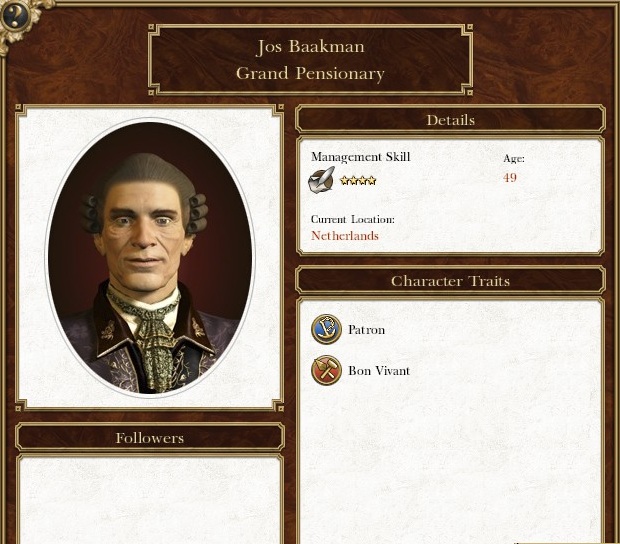

The remainder of the coalition government was Jos Baakman as the head of state. A quintessential Dutchman, Jos Baakman was a patron of the navy, and a man of culture, he had few traits which marked him as a particularly potent politician. Leaving much of his campaigning to the more assertive Friso, he managed to make his way into the position without many qualifications other than that he had few major deficits either.

The remainder of the coalition government was Jos Baakman as the head of state. A quintessential Dutchman, Jos Baakman was a patron of the navy, and a man of culture, he had few traits which marked him as a particularly potent politician. Leaving much of his campaigning to the more assertive Friso, he managed to make his way into the position without many qualifications other than that he had few major deficits either.

Jox Baakman. While a decent politician and a paragon of Dutch virtues, he was not well suited for the position of head of state.

Laurens van Zandt was similar, being a decent account keeper, but was likely less talented at managing a country than his opposition. Zandt was not actually a member of the Republican party, but rather was a member of the V.O.C. party, and his loyalties were still with the V.O.C. His placement in government was almost entirely based around the need for V.O.C. support, with Zandt’s placement in the party as a concession. His actions while in government heavily favoured trade within the Dutch Empire, even as the limited number of potential trade partners dwindled.

Laurens van Zandt was similar, being a decent account keeper, but was likely less talented at managing a country than his opposition. Zandt was not actually a member of the Republican party, but rather was a member of the V.O.C. party, and his loyalties were still with the V.O.C. His placement in government was almost entirely based around the need for V.O.C. support, with Zandt’s placement in the party as a concession. His actions while in government heavily favoured trade within the Dutch Empire, even as the limited number of potential trade partners dwindled.

Laurene van Zandt. He didn't work well with the other members of the Dutch government, as he was normally working towards the interests of the V.O.C. and to trade abroad.

Adelbert Vanderveer was the other V.O.C. party minister. He was minister of war, and had been active in politics in India. While he was used to running a mass scale military, he was used to dealing with significantly more mercenary men than were available in Europe, prompting him to overpay men slightly in the European theater. His highly efficient methods in dealing with the Dutch army however prevented the costs from spiraling out of control.

Adelbert Vanderveer was the other V.O.C. party minister. He was minister of war, and had been active in politics in India. While he was used to running a mass scale military, he was used to dealing with significantly more mercenary men than were available in Europe, prompting him to overpay men slightly in the European theater. His highly efficient methods in dealing with the Dutch army however prevented the costs from spiraling out of control.

Adelbert Vanderveer. While more cooperative with the head of state, Vanderveer still directed more funding and resources towards guaranteeing trade than ending the war.

Also of the Republican Party was Jurgen Neefs, Lord Admiral. For the first time in history, the Dutch had an outright inept naval minister. While he was pleasant and charming, he didn’t spend much time or effort in his actual work, focusing instead on exchanging jokes at the coffee shops in Austria. Mostly when he should have been in Amsterdam.

Also of the Republican Party was Jurgen Neefs, Lord Admiral. For the first time in history, the Dutch had an outright inept naval minister. While he was pleasant and charming, he didn’t spend much time or effort in his actual work, focusing instead on exchanging jokes at the coffee shops in Austria. Mostly when he should have been in Amsterdam.

Jurgen Neefs. Unlike prior Lord Admirals, Neefs was incompetent, it was a wonder that he wasn't fired.

The remaining ministers, those of India and America were also fairly unremarkable men. Astonishingly neither were members of the V.O.C. party. Both were military men who had managed the functioning of the armies when they were around, and both lamented being left out in the colonies to rot. They weren’t functionally superior to domestic ministers, and so both Theodoor van Steenwijck and Albert van Musschenbrock were left largely where they were, hoping their knowledge of their respective theatres would aid stability abroad. However, as India was entirely at peace, and America was mostly at peace, neither would be capable of putting their knowledge of military logistics to use.

The remaining ministers, those of India and America were also fairly unremarkable men. Astonishingly neither were members of the V.O.C. party. Both were military men who had managed the functioning of the armies when they were around, and both lamented being left out in the colonies to rot. They weren’t functionally superior to domestic ministers, and so both Theodoor van Steenwijck and Albert van Musschenbrock were left largely where they were, hoping their knowledge of their respective theatres would aid stability abroad. However, as India was entirely at peace, and America was mostly at peace, neither would be capable of putting their knowledge of military logistics to use.

Theodoor van Steenwijck. He had several useful skills, but nothing to use them on.

The Dutch government wasn’t ideal. Concessions were made to grant the Republican party control over the Empire, and the various ministers had never been as fractured as they were in 1750. Lacking unified control over the direction of the nation during a period of such deadly conflict would inevitably lead to some disaster. The only question was what that would be.

The Dutch government wasn’t ideal. Concessions were made to grant the Republican party control over the Empire, and the various ministers had never been as fractured as they were in 1750. Lacking unified control over the direction of the nation during a period of such deadly conflict would inevitably lead to some disaster. The only question was what that would be.

The most stable member of the Dutch government. Though he wasn't technically any more powerful than any other minister in many matters, he was persuasive enough to hold tremendous influence over the Dutch government.

After the election, the Dutch economy had suffered slightly. Many of the factors causing this dip were out of Dutch control. The military costs had risen greatly, both because their defence minister was less competent than their prior, but also because the Dutch continued recruiting more men, increasing the cost of maintaining their army by nearly twenty million guilders per year. This meant far fewer funds were used to expand industry and the Dutch economy, and as tax revenue continued to trend towards a greater and greater percentage of the net profit of the government, the Dutch found their economy slowing.

After the election, the Dutch economy had suffered slightly. Many of the factors causing this dip were out of Dutch control. The military costs had risen greatly, both because their defence minister was less competent than their prior, but also because the Dutch continued recruiting more men, increasing the cost of maintaining their army by nearly twenty million guilders per year. This meant far fewer funds were used to expand industry and the Dutch economy, and as tax revenue continued to trend towards a greater and greater percentage of the net profit of the government, the Dutch found their economy slowing.

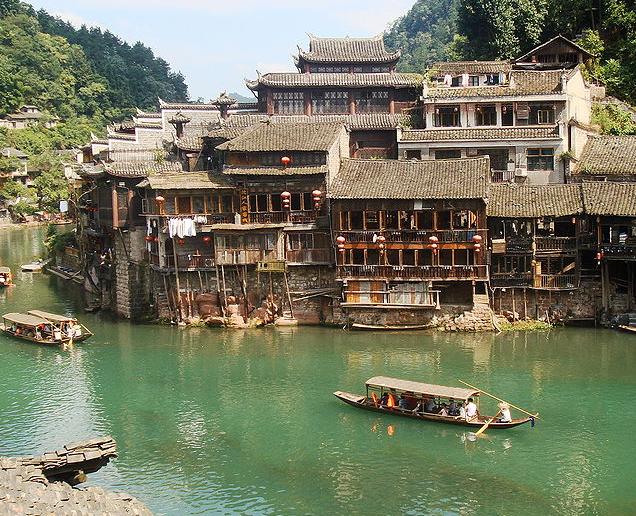

China's population offered a mostly untapped market for the Dutch, the western world increased their focus on Asia and China in particular during the 1800s.

By the mid 1700s, the industrial and scientific boom had slowed down. With the production of a single business matching or exceeding entire nations of the 1600s, the need to improve on factories was diminished. While some humanitarian inventors turned towards making factories safer, and while other political activists were trying to enforce worker rights, for the most part, industry leaders were happy with the state of production. Technology did not stagnate, but little could be done to advance production, or if they could increase production values, the market could not handle the additional products. Prices on former expensive goods such as cotton and wool cloth, iron household utensils and bone china had already been dropped to the lowest they had ever been.

By the mid 1700s, the industrial and scientific boom had slowed down. With the production of a single business matching or exceeding entire nations of the 1600s, the need to improve on factories was diminished. While some humanitarian inventors turned towards making factories safer, and while other political activists were trying to enforce worker rights, for the most part, industry leaders were happy with the state of production. Technology did not stagnate, but little could be done to advance production, or if they could increase production values, the market could not handle the additional products. Prices on former expensive goods such as cotton and wool cloth, iron household utensils and bone china had already been dropped to the lowest they had ever been.

Bone China. The Englishman Spode had determined a means to emulate Asian pottery, and even improve on their techniques in some regards. While production hadn't intensified until the 1800s, the availability of a local alternative cut down the cost of importing it from China somewhat.

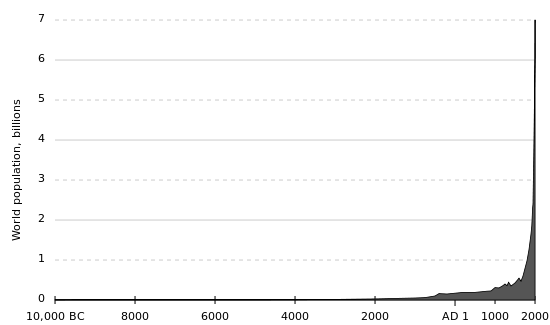

This had meant investment in factories no longer made sense. New businesses often failed, as the established factories were far too dominant to create a space for newcomers. While the economy didn’t crash at that time, the Dutch were desperate to break into new markets. The Dutch were trading with Asia, but at the time did not have the capacity to saturate their enormous market. The Dutch however, were constrained to the current level of industry until the population boom, which would occur in the 1800s and again through the 1900s.

This had meant investment in factories no longer made sense. New businesses often failed, as the established factories were far too dominant to create a space for newcomers. While the economy didn’t crash at that time, the Dutch were desperate to break into new markets. The Dutch were trading with Asia, but at the time did not have the capacity to saturate their enormous market. The Dutch however, were constrained to the current level of industry until the population boom, which would occur in the 1800s and again through the 1900s.

The population growth curve over human history. There was a huge spike in the population starting in around the 1600s.

The Dutch were still the most powerful nation on the world. Attacked in the East and West, the Dutch were on the defensive, but with their southern border secure, this could be the time to attack. Much like Rome however, tension builds within their own borders. Would disaster come from within Dutch borders, or from without? As the Western Atlantic Federation becomes increasingly fractured, what means can be used to cement the nation into a powerful, unified force? And will that force be sufficient to defeat their enemies?

The Dutch were still the most powerful nation on the world. Attacked in the East and West, the Dutch were on the defensive, but with their southern border secure, this could be the time to attack. Much like Rome however, tension builds within their own borders. Would disaster come from within Dutch borders, or from without? As the Western Atlantic Federation becomes increasingly fractured, what means can be used to cement the nation into a powerful, unified force? And will that force be sufficient to defeat their enemies?

The old Roman Empire had spanned much of the European holdings of the Dutch. Much like the Dutch they had enemies around every corner, and an Empire that spanned much of the known world. The Dutch were hoping for a brighter future than their forerunners.

These were the problems the Dutch had to address, and with little time before the British managed to break through the channel, the Dutch had to make their preparations for the years ahead. New army regiments, including the newly raised Holland guard, tasked with keeping Amsterdam in the event of a British attack, hundreds of horses to be kept in reserve or to allow the cavalry the opportunity to rotate their horses, tens of thousands of guns and hundreds of casks of gun powder were all put into production to army thousands more infantry and cavalry. Iron was dredged up from across the Empire to forge new cannon, lead from the Netherlands, America and Spain was mined by the ton for shot, and the total army strength of the Dutch rose from some thirty two thousand to forty thousand by 1755, not including the additional thousands in the navy. With the largest army the world had ever seen put into production, the Dutch could either hold the world at ransom, or go forth and seize it.

These were the problems the Dutch had to address, and with little time before the British managed to break through the channel, the Dutch had to make their preparations for the years ahead. New army regiments, including the newly raised Holland guard, tasked with keeping Amsterdam in the event of a British attack, hundreds of horses to be kept in reserve or to allow the cavalry the opportunity to rotate their horses, tens of thousands of guns and hundreds of casks of gun powder were all put into production to army thousands more infantry and cavalry. Iron was dredged up from across the Empire to forge new cannon, lead from the Netherlands, America and Spain was mined by the ton for shot, and the total army strength of the Dutch rose from some thirty two thousand to forty thousand by 1755, not including the additional thousands in the navy. With the largest army the world had ever seen put into production, the Dutch could either hold the world at ransom, or go forth and seize it. Next we will be presenting more on the culinary history of Great Britain, and where it all went wrong. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be presenting more on the culinary history of Great Britain, and where it all went wrong. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.