Part 31: February 3 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, there will be a special on preparing oneself for Lent. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-first part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the situation in 1753, just prior to the Dutch invasion of 1754.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the thirty-first part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode we discussed the situation in 1753, just prior to the Dutch invasion of 1754. The Dutch were in a state without unity or purpose, and while by late 1753, the Roman government abdicated in favour of Dutch rule after the last of their forces were demolished in a foolhardy sally, the Dutch looked no more willing to actually commit than they had ages before. The Dutch were still being pressured by British raids, and the British still held over seven thousand men along the shore south of London.

The Dutch were in a state without unity or purpose, and while by late 1753, the Roman government abdicated in favour of Dutch rule after the last of their forces were demolished in a foolhardy sally, the Dutch looked no more willing to actually commit than they had ages before. The Dutch were still being pressured by British raids, and the British still held over seven thousand men along the shore south of London.

The British were bracing for the worst the Dutch could throw at them.

But through the slump, the Dutch Channel fleet, led by Gerard van Curen intercepted a British fleet which they spotted near the south coast of Ireland. Expecting British trade ships, sloops, and a few supporting frigates with perhaps a second rate, Curen’s lookout was aghast to report back the presence of several ships of the line, as well as a good number of frigates. The Dutch had been intercepting the same number of ships of the line attempting to probe the Dutch defenses as they had years prior, so the existence of a strong British fleet in addition to the solitary ships that had faced them earlier greatly worried the Dutch.

But through the slump, the Dutch Channel fleet, led by Gerard van Curen intercepted a British fleet which they spotted near the south coast of Ireland. Expecting British trade ships, sloops, and a few supporting frigates with perhaps a second rate, Curen’s lookout was aghast to report back the presence of several ships of the line, as well as a good number of frigates. The Dutch had been intercepting the same number of ships of the line attempting to probe the Dutch defenses as they had years prior, so the existence of a strong British fleet in addition to the solitary ships that had faced them earlier greatly worried the Dutch.

A potent British fleet, likely battered by a Courland force tries to return to port in Ireland for repair.

Curen noted damage to the British ships. The Dutch didn’t have any idea as to whom the British had fought, but it was clear he could not allow the ships into repair, and perhaps they would even be reinforced. If they were, they could possibly destroy the Dutch defenders and invade at land.

Curen noted damage to the British ships. The Dutch didn’t have any idea as to whom the British had fought, but it was clear he could not allow the ships into repair, and perhaps they would even be reinforced. If they were, they could possibly destroy the Dutch defenders and invade at land.

The Dutch fleet rushing to intercept the British before they can make it to port.

The damaged British ships were in no condition to get away from the Dutch fleet, even though they were very fairly close to shore. They turned to face the Dutch, but were in a desperate situation. While the British did have their two second rate ships which outclassed Dutch thirds, the Dutch had three thirds and a heavy one hundred-twenty gun first.

The damaged British ships were in no condition to get away from the Dutch fleet, even though they were very fairly close to shore. They turned to face the Dutch, but were in a desperate situation. While the British did have their two second rate ships which outclassed Dutch thirds, the Dutch had three thirds and a heavy one hundred-twenty gun first.

A Dutch 120 gun heavy first rate. Slow, cumbersome and only moderately more powerful than a standard first rate, the vessel was more of a status symbol than efficient weapon of war.

By 1752, the Dutch had also created rocket firing ships, much like the ones the British had invented a few years prior. While the Dutch generally stole naval technology from the British, the Dutch rocket ship was actually independently invented in Orleans. The British fleet lacking either the bomb ketches or rocket ships required to fire indirectly at long range found themselves under an intense hail of rocket fire which ignited many of their vessels. Force into a halt to douse the fires, the British ships ended up in a mass in the center, many too concerned putting out fires to fight back.

By 1752, the Dutch had also created rocket firing ships, much like the ones the British had invented a few years prior. While the Dutch generally stole naval technology from the British, the Dutch rocket ship was actually independently invented in Orleans. The British fleet lacking either the bomb ketches or rocket ships required to fire indirectly at long range found themselves under an intense hail of rocket fire which ignited many of their vessels. Force into a halt to douse the fires, the British ships ended up in a mass in the center, many too concerned putting out fires to fight back.

The British rocket design. The Dutch version differed primarily in that the shell included a lead counter weight to balance out the guiding pole.

The Dutch thirds used the chaos of the fires to begin circling the British ships, firing broadside after broadside into the mass from afar, keeping at a consistent distance. British return fire was sporadic and ineffective, but the second rates still caused considerable damage when the Dutch moved into the radius of their broadsides.

The Dutch thirds used the chaos of the fires to begin circling the British ships, firing broadside after broadside into the mass from afar, keeping at a consistent distance. British return fire was sporadic and ineffective, but the second rates still caused considerable damage when the Dutch moved into the radius of their broadsides.

Third rates do a pass around the British knot.

The third rates and fire ships pinning down the British vessels, caught in a mass were stuck long enough for the Dutch heavy first rate to come across them, firing a crippling broadside. The devastation brought about by the heavy first forced the desperate British force into action. Frigates, sloops and brigs moved quickly from the safety of the larger second rates trying to silence the Dutch rocket ships and bomb ketches. Their cannon fire quickly pushed the Dutch support ships out of line, and with the heavier Dutch ships on a pass behind the British fleet Dutch frigates were in position to assist, but they were unable to prevent the loss of their support vessels.

The third rates and fire ships pinning down the British vessels, caught in a mass were stuck long enough for the Dutch heavy first rate to come across them, firing a crippling broadside. The devastation brought about by the heavy first forced the desperate British force into action. Frigates, sloops and brigs moved quickly from the safety of the larger second rates trying to silence the Dutch rocket ships and bomb ketches. Their cannon fire quickly pushed the Dutch support ships out of line, and with the heavier Dutch ships on a pass behind the British fleet Dutch frigates were in position to assist, but they were unable to prevent the loss of their support vessels.

British brigs get among the Dutch rocket ships. The Spartiate was left to defend them, but was unable to push them back before the rocket ships were knocked out of the battle.

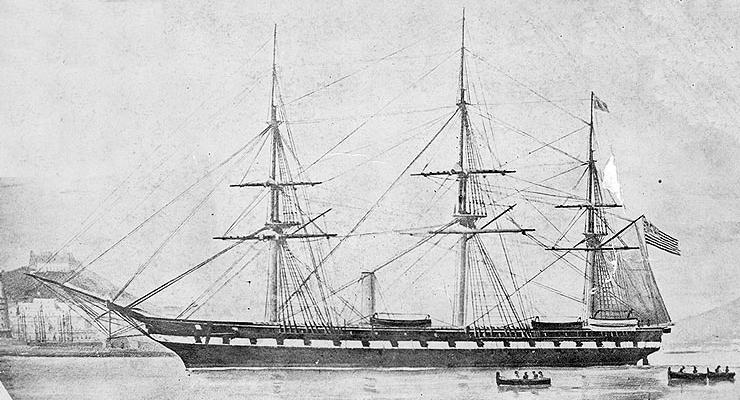

The experimental steam ship saw little action in that battle. With the wind against the British fleet heading into port, it had been elected to stay far and abroad from the main fleet intercepting and destroying any ships that tried to break free from the battle. With so many fires spreading through the British fleet, the manoeuvrable steam ship was not required. However, the principle of the vessel demonstrated a strategic advantage that could not be attained with vessels under sail. The ability to position itself strategically without regards to the prevailing winds would revolutionize sea warfare, though the fruits of that revolution would not be seen until the 1800s.

The experimental steam ship saw little action in that battle. With the wind against the British fleet heading into port, it had been elected to stay far and abroad from the main fleet intercepting and destroying any ships that tried to break free from the battle. With so many fires spreading through the British fleet, the manoeuvrable steam ship was not required. However, the principle of the vessel demonstrated a strategic advantage that could not be attained with vessels under sail. The ability to position itself strategically without regards to the prevailing winds would revolutionize sea warfare, though the fruits of that revolution would not be seen until the 1800s.

The USS Roanoke, a screw propelled steam ship of the mid 1800s. The smaller under gunned steam powered frigates had significantly fewer cannons, yet often had thicker hulls. The change as the century progressed was in improving the penetration and caliber of each individual cannon culminating in the massive above 300 mm cannons used by battleships. In the 1750s where cannon technology did not permit such massive guns, the steam ships were incapable of matching the fire power of heavier ships.

The Dutch had cleared the channel of an enormous British fleet that they had no knowledge of prior to contact. This was a point of tremendous consternation for the Dutch government who had assumed they knew the position of all of the British fleets at that time, and that the British naval strength would climb not much higher than three second rates and its supporting vessels in a season. The appearance of that fleet, which had clearly been used to defend against another threat demonstrated a strength far greater than the Dutch had assumed in previous years.

The Dutch had cleared the channel of an enormous British fleet that they had no knowledge of prior to contact. This was a point of tremendous consternation for the Dutch government who had assumed they knew the position of all of the British fleets at that time, and that the British naval strength would climb not much higher than three second rates and its supporting vessels in a season. The appearance of that fleet, which had clearly been used to defend against another threat demonstrated a strength far greater than the Dutch had assumed in previous years. Now the Dutch government was afraid, and they demanded action as soon as possible. With their preconceived knowledge of the British naval strength absolutely shattered, the Dutch were under no assumptions that their shores were safe. The opposition demanded an attack on British soil as soon as possible, and even the Republican party began facing schisms within its ranks. The appearance of that powerful British fleet was the catalyst that finally led to the invasion of the British isles.

Now the Dutch government was afraid, and they demanded action as soon as possible. With their preconceived knowledge of the British naval strength absolutely shattered, the Dutch were under no assumptions that their shores were safe. The opposition demanded an attack on British soil as soon as possible, and even the Republican party began facing schisms within its ranks. The appearance of that powerful British fleet was the catalyst that finally led to the invasion of the British isles.

The British ships, thankfully already battered were dispatched quickly by the Dutch navy. The death of the British fleet however, did not put the Dutch to ease.

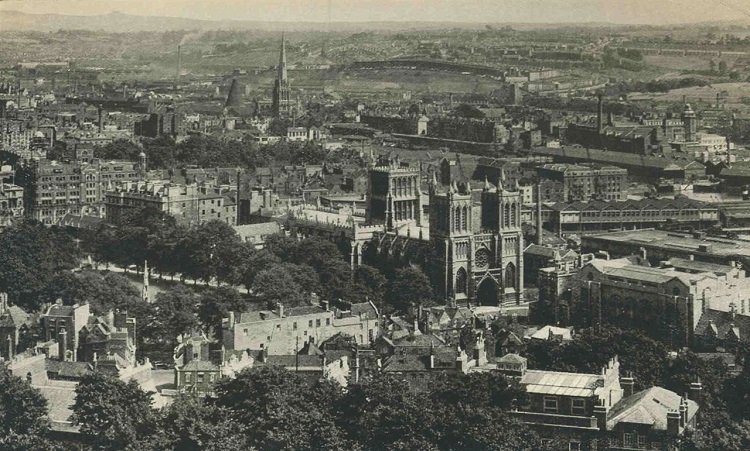

The attack plan they ended up with was rushed, and almost catastrophically so. Two armies, one which had arrived from America would be sent, while another from the Italian theater would land near Bristol to fight the main body of British defenders while the Amsterdam guard army would cross below London hoping the British would send their forces to defeat the first two Dutch armies. These Dutch armies totalled only three thousand men to be sent to Bristol while another one and a half thousand were to be sent to London. Opposing them were eight thousand men or more. The Dutch had been optimistic enough to assume that their Bristol armies would manage to kill at least twice their number, leaving the guard to deal with only three thousand hopefully out of position men.

The attack plan they ended up with was rushed, and almost catastrophically so. Two armies, one which had arrived from America would be sent, while another from the Italian theater would land near Bristol to fight the main body of British defenders while the Amsterdam guard army would cross below London hoping the British would send their forces to defeat the first two Dutch armies. These Dutch armies totalled only three thousand men to be sent to Bristol while another one and a half thousand were to be sent to London. Opposing them were eight thousand men or more. The Dutch had been optimistic enough to assume that their Bristol armies would manage to kill at least twice their number, leaving the guard to deal with only three thousand hopefully out of position men.

The Dutch first wave makes their landing on British soil.

The British were still in control of their ports and so the Dutch were denied the opportunity to land their troops quickly and assault London quickly. Instead they were stuck disembarking their men over months of time onto the shores of England. The Dutch troops from America and Italy were both dropped onto shore and essentially stranded, the British having ample time to manoeuvre their armies to intercept them.

The British were still in control of their ports and so the Dutch were denied the opportunity to land their troops quickly and assault London quickly. Instead they were stuck disembarking their men over months of time onto the shores of England. The Dutch troops from America and Italy were both dropped onto shore and essentially stranded, the British having ample time to manoeuvre their armies to intercept them.

Bristol. The harbour was too heavily defended, and so the Dutch were forced to make a landing to the south delaying the assault considerably.

The first battle of Bristol took place in August of 1754, and involved the British counter attacking the Dutch army that came from the Americas. While the bulk of the British army was holding the other Dutch armies in place, they sent a smaller force of powerful grenadiers, guard and line infantry which they hoped would overwhelm the much larger Dutch force without expending many of their assets which would then be used to wipe out the smaller Dutch force from Italy.

The first battle of Bristol took place in August of 1754, and involved the British counter attacking the Dutch army that came from the Americas. While the bulk of the British army was holding the other Dutch armies in place, they sent a smaller force of powerful grenadiers, guard and line infantry which they hoped would overwhelm the much larger Dutch force without expending many of their assets which would then be used to wipe out the smaller Dutch force from Italy.

The Dutch forces are split after landing ashore, the army which had come from Italy to the East is kept in check while the other was attacked.

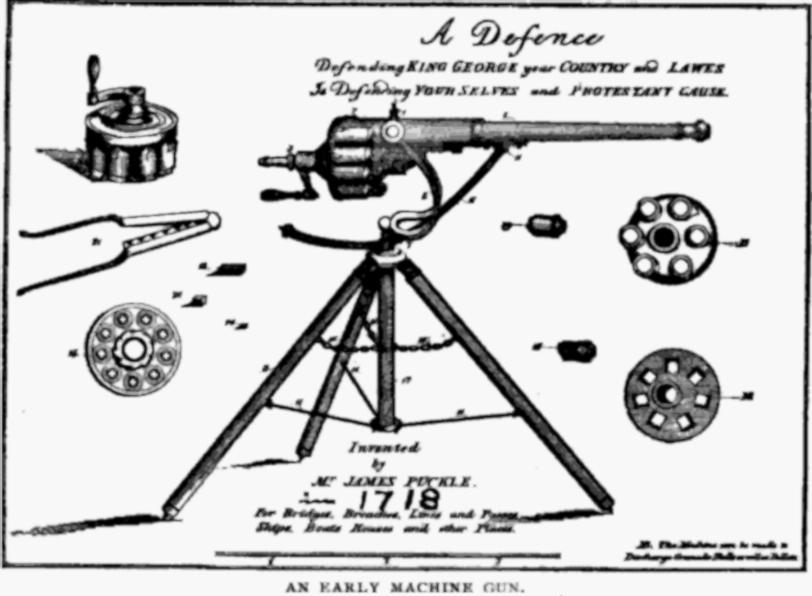

With no reinforcements from either side, the Dutch could pull a victory together, though the British were far more motivated to win than the Dutch had ever seen. Now that the British were defending their home soil, the Dutch were astonished at the ferocity of the attack. Astonishing as well were the battalions and artillery that they had never seen in the Americas before. The British House Guard Cavalry, and the experimental Puckle machine gun were all new additions to the British arsenal, and both were deadly.

With no reinforcements from either side, the Dutch could pull a victory together, though the British were far more motivated to win than the Dutch had ever seen. Now that the British were defending their home soil, the Dutch were astonished at the ferocity of the attack. Astonishing as well were the battalions and artillery that they had never seen in the Americas before. The British House Guard Cavalry, and the experimental Puckle machine gun were all new additions to the British arsenal, and both were deadly.

The Puckle gun, an experimental early model machine gun. The design was not popular with the military, and so few were built, but later refinements on the concept would become staples of the army by the 1900s.

The Dutch arranged themselves much as they would have in America, knowing that with the light infantry they could win a musket to musket battle, and that they were safe from a direct cavalry assault thanks to their rows of spikes driven in front of their lines. This formation seemed to serve the Dutch well, as the British cavalry were forced back, and their volleys tore through the British lines.

The Dutch arranged themselves much as they would have in America, knowing that with the light infantry they could win a musket to musket battle, and that they were safe from a direct cavalry assault thanks to their rows of spikes driven in front of their lines. This formation seemed to serve the Dutch well, as the British cavalry were forced back, and their volleys tore through the British lines.

A British cavalry charge is repelled by the Dutch from behind their field fortifications.

What was different this time was the sheer ferocity of the British armies. Discarding their muskets, the British army pushed forward in a devastating bayonet charge, pushing straight through the Dutch light infantry and killing hundreds of the line infantry of the Dutch defenders. The Dutch, unable to bring their superior numbers of muskets to bear took horrendous losses and even lost their center, but were able to swamp the British assailants with sheer numbers. Though the British were proving themselves more than a match for the Dutch but after a prolonged struggled in melee the British troops began to falter and were pushed back.

What was different this time was the sheer ferocity of the British armies. Discarding their muskets, the British army pushed forward in a devastating bayonet charge, pushing straight through the Dutch light infantry and killing hundreds of the line infantry of the Dutch defenders. The Dutch, unable to bring their superior numbers of muskets to bear took horrendous losses and even lost their center, but were able to swamp the British assailants with sheer numbers. Though the British were proving themselves more than a match for the Dutch but after a prolonged struggled in melee the British troops began to falter and were pushed back.

The British charge straight into the Dutch lines. Though they had received many casualties advancing, the momentum of the charge still severely damaged the Dutch center.

As the British infantry sounded the retreat, only a hundred of them remaining, their experimental machine gun opened up on the Dutch line. Advancing to try and spike the British artillery, the Dutch found themselves being whittled down and picked apart by the new device. Though the Dutch could overwhelm it with sheer numbers leaving a trail of dead bodies in their line of advance, it showed tremendous potential which would be exploited heavily a century later. Even in the first battle of Bristol, dozens of Dutch soldiers had been gunned down in but a few minutes, the only limitation being the short range it could be accurately fired to.

As the British infantry sounded the retreat, only a hundred of them remaining, their experimental machine gun opened up on the Dutch line. Advancing to try and spike the British artillery, the Dutch found themselves being whittled down and picked apart by the new device. Though the Dutch could overwhelm it with sheer numbers leaving a trail of dead bodies in their line of advance, it showed tremendous potential which would be exploited heavily a century later. Even in the first battle of Bristol, dozens of Dutch soldiers had been gunned down in but a few minutes, the only limitation being the short range it could be accurately fired to.

Dutch line infantry take the British machine guns, leaving a steady trail of dead and wounded men on the charge towards it. Limited by poor accuracy even for the era, the Puckle machine gun was vulnerable when it wasn't supported.

The battle was pyrrhic however. The Dutch had lost eight hundred men, and had killed only a thousand. The Dutch were reduced to approximately two thousand men near Bristol, and three and a half thousand overall against over seven thousand British defenders. The Dutch however, still held out on the hope that they could severely damage the British army in a November counter assault, which was when the Dutch guard would land below London.

The battle was pyrrhic however. The Dutch had lost eight hundred men, and had killed only a thousand. The Dutch were reduced to approximately two thousand men near Bristol, and three and a half thousand overall against over seven thousand British defenders. The Dutch however, still held out on the hope that they could severely damage the British army in a November counter assault, which was when the Dutch guard would land below London.

Dead from both sides litter the field. While the Dutch were still intact, the British had forced them into a victory they could not afford.

The second battle of Bristol, fought in the same year involved two thousand Dutch defenders against over six thousand English assailants. The Dutch and their general Crieckenbeeck had not been informed of their role in that battle, and had expected perhaps three thousand British soldiers, a battle which they very well could have managed. It is rumoured that the much more savvy Vrooman had been somewhat aware of the situation, and may have retired to avoid the suicidal job.

The second battle of Bristol, fought in the same year involved two thousand Dutch defenders against over six thousand English assailants. The Dutch and their general Crieckenbeeck had not been informed of their role in that battle, and had expected perhaps three thousand British soldiers, a battle which they very well could have managed. It is rumoured that the much more savvy Vrooman had been somewhat aware of the situation, and may have retired to avoid the suicidal job.

The Dutch lines advance to attack the British, hoping to destroy them.

The Dutch lined up against the first wave of British defenders, who were back behind anti-cavalry spikes had a strange strategy against the Dutch. With numbers far beyond those which the Dutch could handle, the had sent men piecemeal to delay the Dutch lines in artillery range. While these individual battalions were surrounded and destroyed, the always managed to exact a toll on the Dutch lines while the artillery fired into their lines from afar, stopping the Dutch from advancing. As this happened, the main British line was constantly being reinforced and pulling back.

The Dutch lined up against the first wave of British defenders, who were back behind anti-cavalry spikes had a strange strategy against the Dutch. With numbers far beyond those which the Dutch could handle, the had sent men piecemeal to delay the Dutch lines in artillery range. While these individual battalions were surrounded and destroyed, the always managed to exact a toll on the Dutch lines while the artillery fired into their lines from afar, stopping the Dutch from advancing. As this happened, the main British line was constantly being reinforced and pulling back.

British forces sacrificed lines of infantry to delay the Dutch forces both to delay for reinforcements, but also to destroy the Dutch with artillery.

As the Dutch line closed in on the British artillery, the British sent in their cavalry and infantry in a frontal assault. While it was not the entire British line, the Dutch were already starting to strain against the pressure, especially along their flanks which were heavily pressured by British line infantry. Unable to flank them, as the remainder of the line was locked in the center by cavalry, the Dutch flanks were cut down to handfuls of people.

As the Dutch line closed in on the British artillery, the British sent in their cavalry and infantry in a frontal assault. While it was not the entire British line, the Dutch were already starting to strain against the pressure, especially along their flanks which were heavily pressured by British line infantry. Unable to flank them, as the remainder of the line was locked in the center by cavalry, the Dutch flanks were cut down to handfuls of people.

The Dutch receive a British charge across their line. While the British would be repelled, the Dutch lines were finding themselves short on men as the battle wore on.

The Dutch forces were being terribly whittled down along each flank in turn, their reinforcing battalions on their right already down to a fraction of their initial strengths. While the Dutch had been terribly reduced, they managed to push their way to the British artillery which had been dug in. The British forces had mostly pulled back, and appeared to be on approximately equal terms to the Dutch, but reports were coming in to Crieckenbeeck about more and more British reinforcements appearing on their left.

The Dutch forces were being terribly whittled down along each flank in turn, their reinforcing battalions on their right already down to a fraction of their initial strengths. While the Dutch had been terribly reduced, they managed to push their way to the British artillery which had been dug in. The British forces had mostly pulled back, and appeared to be on approximately equal terms to the Dutch, but reports were coming in to Crieckenbeeck about more and more British reinforcements appearing on their left.

The Dutch finally destroy the British artillery battery which had been firing into Dutch forces the entire battle.

Crieckenbeeck hoped that the reinforcing army was a limited force, rather than a column of thousands tricking in by hundreds. He would be disappointed by the reality of the situation. British Grenadiers swept around the Dutch left flank. The Dutch had to try and respond with their cavalry, but the British grenadiers held out, killing hundreds of Dutch cavalry, clearing out the Dutch left.

Crieckenbeeck hoped that the reinforcing army was a limited force, rather than a column of thousands tricking in by hundreds. He would be disappointed by the reality of the situation. British Grenadiers swept around the Dutch left flank. The Dutch had to try and respond with their cavalry, but the British grenadiers held out, killing hundreds of Dutch cavalry, clearing out the Dutch left.

The Dutch battalions holding the flank were being worn down by each unit the British had left behind to delay the Dutch advance creating a weakness along the flanks which the British could exploit and which the Dutch could not cover for lack of numbers.

The Dutch found themselves in a battle of attrition. While their armies which had landed south of Bristol, were being ground to dust, the Dutch assault would continue. Thousands of troops were slated to land even as the second battle of Bristol raged on.

The Dutch found themselves in a battle of attrition. While their armies which had landed south of Bristol, were being ground to dust, the Dutch assault would continue. Thousands of troops were slated to land even as the second battle of Bristol raged on.

Dutch forces land near London, even though the first phase of their assault was going poorly. In Bristol, the battle continues.

Next we will be helping you all prepare yourselves for Lent. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be helping you all prepare yourselves for Lent. In half an hour, we will be presenting world news before returning to Shakespeare for the rest of the evening. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.