Part 40: March 2 Broadcast

You are listening to BBC radio 4. In an hour, professor Stewart will be presenting his findings on Norse relics recovered from the British coast. For the next hour, Professor David Stephenson will be presenting a documentary on the second 80 years war of the eighteenth century. This series will be running every third day, up to 50 episodes. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1.

Good evening, and welcome to BBC radio 4. I’m Professor David Stephenson, professor of Dutch historical studies at Cambridge. This is the fourtieth part of our 50 episode special on the second 80 years war over Europe. Joining me for these broadcasts are fellow researchers and scholars Doctor Albert Andrews, specialist in German studies from the Berlin academy, Professor Robert Lowe, specialist in French studies at Cambridge, and a graduate student and technical assistant, Anton Thatcher. Last episode, we discussed the first moves of the Polish crusade.

The war was progressing at a blistering pace, the Polish forces moving to counter the Dutch advance in Berlin, only to be pushed back at Magdeburg. Breslau, Prague and Munich had all been invested by their respective assailants, and thousands of men were rushed to the fore.

The war was progressing at a blistering pace, the Polish forces moving to counter the Dutch advance in Berlin, only to be pushed back at Magdeburg. Breslau, Prague and Munich had all been invested by their respective assailants, and thousands of men were rushed to the fore.

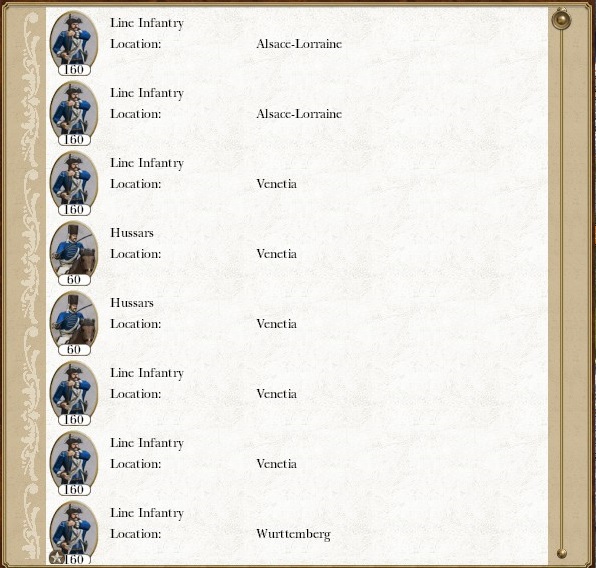

Thousands of soldiers were brought up and immediately departed to the fore from all across Europe. The sheer manpower the Dutch could draw up at a moments notice was almost overwhelming, but the cost of upkeep meant their net profits had fallen below trade independent levels once more.

During the battle of Magdeburg in the same miserable rain, the forces of Prague attempted to break through the Dutch lines. Strijders had formed into two groups to push away the second force of Polish defenders just days before, and had not returned into a consolidated force before the counter attack, meaning his investment force was separated from his main army.

During the battle of Magdeburg in the same miserable rain, the forces of Prague attempted to break through the Dutch lines. Strijders had formed into two groups to push away the second force of Polish defenders just days before, and had not returned into a consolidated force before the counter attack, meaning his investment force was separated from his main army.

The invested forces trying to hold down the Polish forces while the main force pushes away reinforcements. Their task was to hold the Polish forces at bay long enough for the main army to return and destroy the Polish army.

A tactical error certainly, but not one that could have been avoided. His own forces were to the North-West of the fortress around Prague, while the fortress was being held in check by infantry and cavalry to the south. The attack came as Strijders was marching back from the North to continue the siege. The Polish forces had hoped to manage a quick strike, rapidly destroy the lesser Dutch force to their South before swinging back North to finish off the remainder of the Dutch forces, or if necessary, retreat to their fortress to await reinforcements from Warsaw.

A tactical error certainly, but not one that could have been avoided. His own forces were to the North-West of the fortress around Prague, while the fortress was being held in check by infantry and cavalry to the south. The attack came as Strijders was marching back from the North to continue the siege. The Polish forces had hoped to manage a quick strike, rapidly destroy the lesser Dutch force to their South before swinging back North to finish off the remainder of the Dutch forces, or if necessary, retreat to their fortress to await reinforcements from Warsaw.

Dutch reinforcements arrive along the flank of the Polish forces.

The Polish attack was done along two fronts. The vast majority of their forces were deployed to defeat the Dutch regiment encamped overlooking their fortress from the South, while their cavalry and artillery was deployed North to try and delay the Dutch forces through harassment. A few battalions of line were moved to block the Dutch from taking the fortress if they decided to abandon their men in the South to capture Prague.

The Polish attack was done along two fronts. The vast majority of their forces were deployed to defeat the Dutch regiment encamped overlooking their fortress from the South, while their cavalry and artillery was deployed North to try and delay the Dutch forces through harassment. A few battalions of line were moved to block the Dutch from taking the fortress if they decided to abandon their men in the South to capture Prague.

The Dutch run across a regiment of Polish line meant to hold them in place as their army advanced and encircled the South force.

Strijders managed to show great character by preferring the lives of his men over a quick victory at Prague, and as his forces moved into the field, they immediately set about counter attacking the Polish forces arrayed in front of them. The Dutch needed to break past them to get to their smaller force in the South, and could not afford the mistake of a rapid march through enemy fire to their aid. Leaving the fortress, he opted to relieve his Southern forces.

Strijders managed to show great character by preferring the lives of his men over a quick victory at Prague, and as his forces moved into the field, they immediately set about counter attacking the Polish forces arrayed in front of them. The Dutch needed to break past them to get to their smaller force in the South, and could not afford the mistake of a rapid march through enemy fire to their aid. Leaving the fortress, he opted to relieve his Southern forces.

The first Dutch line to contact the Polish center. Able to make a break through the fierce fire fight at the North, these troops tied up men intended to flank the Dutch forces to the South.

In the South, the infantry were menaced by both infantry and cavalry, forcing their right flank into squares. They moved back into line as the infantry closed, and used their sole regiment of horse to keep the Polish cavalry at bay, but even with the high ground their position was not tenable. They had to carefully maneuver along to their left to keep away from the advancing Polish infantry, but at the same time, the Polish had sent another wing to split the South and Northern forces from linking up. By moving too close to these, the Dutch would find themselves outmatched.

In the South, the infantry were menaced by both infantry and cavalry, forcing their right flank into squares. They moved back into line as the infantry closed, and used their sole regiment of horse to keep the Polish cavalry at bay, but even with the high ground their position was not tenable. They had to carefully maneuver along to their left to keep away from the advancing Polish infantry, but at the same time, the Polish had sent another wing to split the South and Northern forces from linking up. By moving too close to these, the Dutch would find themselves outmatched.

The Dutch South force was delaying engagement as long as possible, but did not wish to abandon the high ground. If desperate, they could charge with the momentum of the hill, and hope to break through the Polish lines.

The Dutch in the North of the battle managed to arrange in line across a wide frontage, light infantry within spitting distance of the enemy line, backed directly by their own line. The sheer volume of fire was rapidly thinning the ranks of the men sent to block them, as they had deployed far too close to Dutch lines. With Dutch artillery causing terrible havoc at long range, they could not allow the Dutch infantry an opportunity to consolidate their position into a strong point and send detachments to assist under cover of artillery fire.

The Dutch in the North of the battle managed to arrange in line across a wide frontage, light infantry within spitting distance of the enemy line, backed directly by their own line. The sheer volume of fire was rapidly thinning the ranks of the men sent to block them, as they had deployed far too close to Dutch lines. With Dutch artillery causing terrible havoc at long range, they could not allow the Dutch infantry an opportunity to consolidate their position into a strong point and send detachments to assist under cover of artillery fire.

Dutch infantry push through the Polish blockade. Tied up fighting these Polish troops, many Dutch could not quickly move to counter in the South.

The last remaining forces in the North were losing, but were tying down a considerable number of Dutch forces. Three battalions of light infantry, a battalion of line infantry were all held back by a very small number of Polish infantry. Strijders actually broke through personally, unable to wait to bring his line to the Southern battle ground.

The last remaining forces in the North were losing, but were tying down a considerable number of Dutch forces. Three battalions of light infantry, a battalion of line infantry were all held back by a very small number of Polish infantry. Strijders actually broke through personally, unable to wait to bring his line to the Southern battle ground.

Even as Strijders defeated the last of the Polish forces holding a part of his army back, battalions that had broken free were pushing their way to their colleagues.

As the remaining Dutch finally broke free of the Polish blocking forces, the Polish came to grips with the Dutch South force. Rather than continue to keep the Dutch in check to the North, the Polish committed their guard and remaining forces in a strong charge against the surrounded Dutch forces. The Dutch, too proud to be outdone fixed bayonets and charged directly downhill into the Polish lines. The desperation of their charge shocked the Polish forces letting the Dutch get considerable casualties against them. Even so, all that remained of them were two bloodied battalions by the time the first battalion of reinforcements managed to arrive. Retreating back behind the remaining Dutch forces to recuperate, while the last of the Polish garrison was pushed back into their fortress around Prague.

As the remaining Dutch finally broke free of the Polish blocking forces, the Polish came to grips with the Dutch South force. Rather than continue to keep the Dutch in check to the North, the Polish committed their guard and remaining forces in a strong charge against the surrounded Dutch forces. The Dutch, too proud to be outdone fixed bayonets and charged directly downhill into the Polish lines. The desperation of their charge shocked the Polish forces letting the Dutch get considerable casualties against them. Even so, all that remained of them were two bloodied battalions by the time the first battalion of reinforcements managed to arrive. Retreating back behind the remaining Dutch forces to recuperate, while the last of the Polish garrison was pushed back into their fortress around Prague.

Dutch forces in a desperate last charge. While only a fraction would survive, their brave charge would give them enough time for the remaining Dutch forces to arrive, pushing away the Polish forces.

Strijders had shown qualities rare in a European general of the age. He disdained personal danger, and had a clear conscious through the battle, preserving as many men as he possibly could. His tactics were not brilliant. A superior general would have moved most of his forces in the final counter attack against the Polish assaulting to the South, and the remainder to block them from returning to Prague, but Strijders had wanted to break through to the South as fast as possible, and so committed every battalion in his force to an attack that required perhaps only three quarters.

Strijders had shown qualities rare in a European general of the age. He disdained personal danger, and had a clear conscious through the battle, preserving as many men as he possibly could. His tactics were not brilliant. A superior general would have moved most of his forces in the final counter attack against the Polish assaulting to the South, and the remainder to block them from returning to Prague, but Strijders had wanted to break through to the South as fast as possible, and so committed every battalion in his force to an attack that required perhaps only three quarters.

Every Dutch battalion was working their way up the same hill towards the remaining Polish forces.

In any event, the Polish were kept locked in Prague meaning they could not attempt a second breakthrough at Breslau with the forces from a successful breakthrough. This left them with only Munich to fight their opening moves. Outnumbered, without cannon and forced into an assault, the Polish army perhaps knew something the Dutch didn’t.

In any event, the Polish were kept locked in Prague meaning they could not attempt a second breakthrough at Breslau with the forces from a successful breakthrough. This left them with only Munich to fight their opening moves. Outnumbered, without cannon and forced into an assault, the Polish army perhaps knew something the Dutch didn’t.

The Polish attack a Dutch fortress directly with no artillery.

And it’s very likely that they did. A small number of Catholic traitors and conspirators from around Innsbruck, mostly a small number of survivors from the war against the Dutch in the initial years managed to detonate kegs of black powder under the foundations of the Dutch North wall. The blast destroyed the North East face, but not the North West face, merely damaging it. Dutch intelligence of the age had surmised the motivation was the destruction of the famed Innsbruck Cathedral, replaced with factories. While papers and documents regarding the conspiracy were found, no one was ever tied to them.

And it’s very likely that they did. A small number of Catholic traitors and conspirators from around Innsbruck, mostly a small number of survivors from the war against the Dutch in the initial years managed to detonate kegs of black powder under the foundations of the Dutch North wall. The blast destroyed the North East face, but not the North West face, merely damaging it. Dutch intelligence of the age had surmised the motivation was the destruction of the famed Innsbruck Cathedral, replaced with factories. While papers and documents regarding the conspiracy were found, no one was ever tied to them.

A recreation of the Innsbruck cathedral. The original was demolished to make way for more factories, but their relics were preserved in the Hofburg.

The blast fortunately occurred prematurely by several crucial minutes when the Polish army was still beyond sight of the Dutch forces. It is possible that they had been delayed from the appointed time by foul weather, and the conspirators, none of whom were identified had no way to adjust their timetables. So early on, the walls were largely empty rather than covered in defenders.

The blast fortunately occurred prematurely by several crucial minutes when the Polish army was still beyond sight of the Dutch forces. It is possible that they had been delayed from the appointed time by foul weather, and the conspirators, none of whom were identified had no way to adjust their timetables. So early on, the walls were largely empty rather than covered in defenders.

The Dutch wall was breached through sabotage before battle was met. Two sections of wall were sapped, but only one collapsed. Defective powder due to a higher moisture content in the second sap was to blame.

This left the Polish army with a single gap to exploit, as they had brought no artillery. They had evidently hoped for a second breach to open permitting greater freedom of movement into the Dutch fortress, and fewer men manning the walls.

This left the Polish army with a single gap to exploit, as they had brought no artillery. They had evidently hoped for a second breach to open permitting greater freedom of movement into the Dutch fortress, and fewer men manning the walls.

Polish forces make for the breach.

Instead, the Dutch set their cannon to fire directly into the gap with grape shot. Anyone moving through that corridor would find nothing but a wall of shot directed at them. Much of their remaining forces were spread across the rest of the walls, but two battalions of line were held to force the gap into a funnel of gunfire, and a third battalion held the center as a reserve.

Instead, the Dutch set their cannon to fire directly into the gap with grape shot. Anyone moving through that corridor would find nothing but a wall of shot directed at them. Much of their remaining forces were spread across the rest of the walls, but two battalions of line were held to force the gap into a funnel of gunfire, and a third battalion held the center as a reserve.

The Dutch adopt a standard breach defense against their Polish assailants.

The Dutch forces along the walls managed to take their shots at the advancing Polish forces who were trying to get across a weak point. They didn’t want to commit their full forces to the gap, as they knew it would be a kill zone well defended by the Dutch by then. Instead, while some battalions formed into a forlorn hope to try and spike the cannons directly, the vast majority of their forces were forced to assault the walls directly. With only one battery of cannon, the Dutch could not have committed to this defense if the wall had collapsed on both sides of their gate house, but as one had remained standing, though battered, the Polish were less capable of a direct assault.

The Dutch forces along the walls managed to take their shots at the advancing Polish forces who were trying to get across a weak point. They didn’t want to commit their full forces to the gap, as they knew it would be a kill zone well defended by the Dutch by then. Instead, while some battalions formed into a forlorn hope to try and spike the cannons directly, the vast majority of their forces were forced to assault the walls directly. With only one battery of cannon, the Dutch could not have committed to this defense if the wall had collapsed on both sides of their gate house, but as one had remained standing, though battered, the Polish were less capable of a direct assault.

Dutch forces fire from the walls into the exposed Polish forces. As the Polish attempted to find a weak point, they were exposed to constant fire.

Now aware of the side the Polish would be attacking from, the Dutch cavalry moved away from the fortifications to try and sweep the enemy infantry from the field as they tried to scale the walls. Men busy scaling the walls could easily be put into a panic when assaulted from behind when their backs were to a wall. To counter this, Polish cavalry fought ferociously with the Dutch regiment of horse.

Now aware of the side the Polish would be attacking from, the Dutch cavalry moved away from the fortifications to try and sweep the enemy infantry from the field as they tried to scale the walls. Men busy scaling the walls could easily be put into a panic when assaulted from behind when their backs were to a wall. To counter this, Polish cavalry fought ferociously with the Dutch regiment of horse.

Dutch and Polish cavalry clash outside the Dutch walls. The Dutch needed to sweep the Polish forces away from the walls, Polish cavalry moved to intercept and block them.

However, the Polish force, not needing a strong cavalry contingent to fight a siege had committed their provincial cavalry to Munich. These men proved to be a poor match for the Dutch regiment of horse who drove them from the field before making a drive at the Polish artillery.

However, the Polish force, not needing a strong cavalry contingent to fight a siege had committed their provincial cavalry to Munich. These men proved to be a poor match for the Dutch regiment of horse who drove them from the field before making a drive at the Polish artillery.

Dutch cavalry were able to defeat the Polish provincial cavalry. Had the Polish fielded their guard or winged hussars, the Dutch regiment of horse would have been no match.

The Polish force, as mentioned had no cannon and no Howitzers. Instead, they had a strange contraption of familiar design. A British designed rapid firing gun. It was clear that even though the British were not able to directly assist the Polish against the Dutch, they were able to lend some support. Fortunately, the artillery piece was used incorrectly, scouring the Dutch wall harmlessly with bullets. The Polish army clearly did not understand the purpose of the gun, and had thought to employ it as any other artillery piece, hoping the gun would chip away the wall. Left vulnerable, and not used to gun down the cavalry bearing down on them, the Dutch easily cleared them from the field.

The Polish force, as mentioned had no cannon and no Howitzers. Instead, they had a strange contraption of familiar design. A British designed rapid firing gun. It was clear that even though the British were not able to directly assist the Polish against the Dutch, they were able to lend some support. Fortunately, the artillery piece was used incorrectly, scouring the Dutch wall harmlessly with bullets. The Polish army clearly did not understand the purpose of the gun, and had thought to employ it as any other artillery piece, hoping the gun would chip away the wall. Left vulnerable, and not used to gun down the cavalry bearing down on them, the Dutch easily cleared them from the field.

Rather than defend their rudimentary machine guns and use them to fire at the oncoming Dutch regiments of horse, the Polish artillery piece fired into the Dutch walls before being run down.

By then, the battle had moved into a phase of clear Dutch supremacy. Their forces kept the Polish assault from taking the walls by raking their infantry with fire as they tried to scale up them. While the Polish guard had shown enough fortitude to climb into the sharp crack of the Dutch musket fire from above, their support had been pushed back, and once atop the walls, they could not defeat the Dutch line infantry in melee alone. While they were able to account for a considerable number of deaths caused, they could not compete with the sheer numbers, especially as a third of their number were killed climbing into the gunfire.

By then, the battle had moved into a phase of clear Dutch supremacy. Their forces kept the Polish assault from taking the walls by raking their infantry with fire as they tried to scale up them. While the Polish guard had shown enough fortitude to climb into the sharp crack of the Dutch musket fire from above, their support had been pushed back, and once atop the walls, they could not defeat the Dutch line infantry in melee alone. While they were able to account for a considerable number of deaths caused, they could not compete with the sheer numbers, especially as a third of their number were killed climbing into the gunfire. In the gap, the Polish infantry were being gunned down without mercy. They knew the gap would be the worst killing zone, but with failure in all other locations, it was their last chance. With grape well ranged into the gap, and hundreds of muskets leveled at it, the Polish forces had failed.

In the gap, the Polish infantry were being gunned down without mercy. They knew the gap would be the worst killing zone, but with failure in all other locations, it was their last chance. With grape well ranged into the gap, and hundreds of muskets leveled at it, the Polish forces had failed.

The last of the Polish forces retreat from the battle field.

This battle demonstrated an important lesson to both sides. The Dutch in their confidence had not considered the conspirators that would act against them working covertly from within their military. The Polish army had made a grave miscalculation in assuming the works of the saboteurs would lead to victory when in reality, they needed to assist this subterfuge with artillery as one properly should in a siege. Lacking any artillery, the Polish could not thin down the defenders from range, nor could they open additional breaches in the Dutch walls.

This battle demonstrated an important lesson to both sides. The Dutch in their confidence had not considered the conspirators that would act against them working covertly from within their military. The Polish army had made a grave miscalculation in assuming the works of the saboteurs would lead to victory when in reality, they needed to assist this subterfuge with artillery as one properly should in a siege. Lacking any artillery, the Polish could not thin down the defenders from range, nor could they open additional breaches in the Dutch walls.

The Polish forces retreat to the town of Budweis. From then on, generals would be more tentative about assaulting a fortress without artillery, even if breached.

For the Polish forces, the answer was obvious, but perhaps learned too disastrously. Thousands lay dead in the fields around Munich, and the remainder were run down by a small detachment from Vienna. They had discarded artillery to move to Munich faster, but this had not aided them as much as artillery would have. In future, even where agents were available to sabotage Dutch fortifications and armies, the Polish would bring artillery to bear in a siege battle.

For the Polish forces, the answer was obvious, but perhaps learned too disastrously. Thousands lay dead in the fields around Munich, and the remainder were run down by a small detachment from Vienna. They had discarded artillery to move to Munich faster, but this had not aided them as much as artillery would have. In future, even where agents were available to sabotage Dutch fortifications and armies, the Polish would bring artillery to bear in a siege battle. The Dutch were left with a much more difficult question. They could not turn to an internal witch hunt against the Catholics, as it went against their official stance of secular humanism. What’s worse, that would be a guaranteed method to incite a civil war between Catholics and Protestants within their own borders. Still, that the saboteurs were still at large meant the Dutch could expect more such actions from their enemies.

The Dutch were left with a much more difficult question. They could not turn to an internal witch hunt against the Catholics, as it went against their official stance of secular humanism. What’s worse, that would be a guaranteed method to incite a civil war between Catholics and Protestants within their own borders. Still, that the saboteurs were still at large meant the Dutch could expect more such actions from their enemies.

Sapping was an effective and common means of breaking down a fortress wall.

Enemies abroad, the Polish army held across the entire front and pushed back from Munich, the Dutch seemed poised for victory. However, with traitors in their ranks, and undiscovered double agents in their armies, the Dutch were less confident about their position and numbers than they perhaps should have been.

Enemies abroad, the Polish army held across the entire front and pushed back from Munich, the Dutch seemed poised for victory. However, with traitors in their ranks, and undiscovered double agents in their armies, the Dutch were less confident about their position and numbers than they perhaps should have been. Next we will be observing and understanding Norse relics found on the coastline of Britain with Professor Stewart followed by world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.

Next we will be observing and understanding Norse relics found on the coastline of Britain with Professor Stewart followed by world news. If you want news of the current war in the Middle East please channel in to BBC radio 1. David Stephenson will be presenting more on the 80 years war in 3 days.