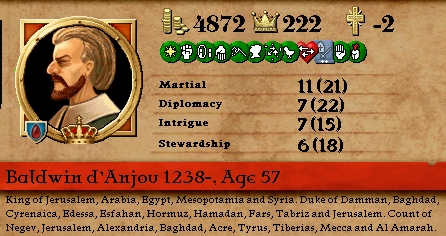

Part 9: IX. The Despised King Girard I 1280-1296 A.D.

It was immediately clear that Girard would not be a popular ruler. His 'kinslayer' trait made him quite unpopular with his vassals. Furthermore, he did not start with the title of Emperor, only the Pope could crown him, and the Pope was delaying.

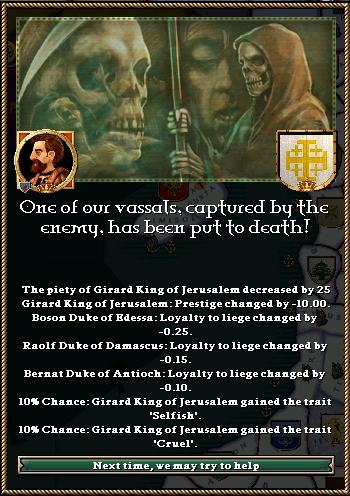

Just weeks after he had taken the crown, sad news came from Baghdad.

His little brother, Guiges, whom Emperor Louis had just made Duke of Baghdad had been captured by local Muslim rebels and beheaded while on procession in the province of Al Nasiryah. The rebellion was surprisingly large, and the first group of soldiers King Girard sent south were temporarily beaten back. It took several more months before the rebellion was fully suppressed and Duke Guiges was avenged.

His widow, Bona, was made Duchess of Mosul.

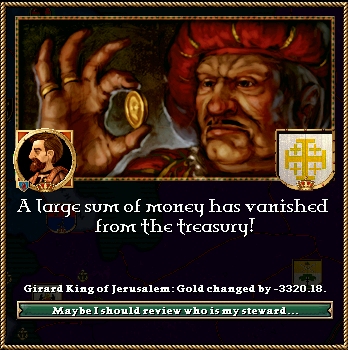

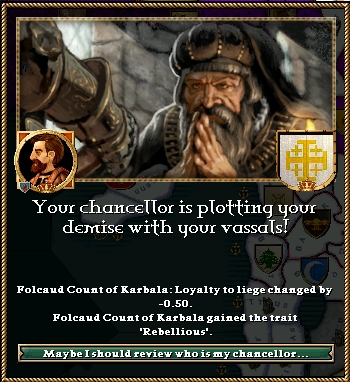

Corruption in Girard's court was common. In June of 1281 a massive amount of gold was stolen from the treasury, plunging the Kingdom several thousand into debt.

But there was no time to hunt for the thieves. In July, Bona, the ungrateful Duchess of Mosul, revolted against King Girard. The duchy of Alexandria followed within a few days.

Mosul

Alexandria

It took six months for Girard to suppress his vassals, but he dared not strip them of their titles. So many of his vassals disliked him that he could not afford the bad reputation of taking the lands of the rebels. That would send him into a death spiral where more and more revolted and each one he conquered made all the others hate him more. Instead he allowed Bona and the Duke of Alexandria to re-swear their oaths of loyalty to the crown. A stop-gap measure, to be sure, but all he could manage at the moment.

King Girard would not have much time to rest. In April of 1282, the Duke of Basra attacked the small, three province Mongolian Khanate of Tabriz. Basra asked King Girard to assist, and he saw no reason not to help. Perhaps it would earn him good will with his other vassals.

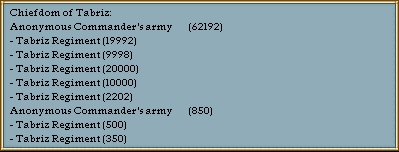

But there was a reason. A good one. Tabriz had just received a fresh batch of Mongolian horse hordes. 60,000 of them, to be exact.

What madness had possessed Basra to attack such a vast army the world would never know.

King Girard gathered what troops he had nearby, a 'mere' ten thousand, and tried to flank around the huge horde. Perhaps if he could strip Tabriz of its capital they would lose heart for the fight. Not all of his soldiers, however, were very enthusiastic about facing such poor odds.

Half his army slipped away, just days before King Girard planned to enter Mongol territory, and he had to pull back and wait for reinforcements. When they finally arrived he attacked Tabriz, the main Mongol forces having rushed forward to attack the holdings of the Duke of Basra.

However stupid the Duke of Basra was, he was certainly courageous. Small groups of loyal Christian troops repeatedly threw themselves at the Mongols, often outnumbered as much as 30 to 1. They didn't do much damage, but they slowed the Mongol advance toward the sea. King Girard followed behind, retaking Tabriz and the other provinces the Mongols stole from his vassals.

During the war, Edessa revolted and was quickly suppressed. Even with the threat of the Mongols moving through Christian lands, many were still willing to take up arms against the despised King Girard. Fortunately, however, the harvests were prosperous, and King Girard was able to gather and extra 3000 gold, bringing the Kingdom out of debt.

16,000 troops were raised from Alexandria and enough others were scraped up to bring the Kingdom army to around 35,000. Although the Mongols were immune to attrition, constant skirmishes with small Christian vassal states had worn their main force down to 40,000.

King Girard felt he had a chance. If his army was defeated, the Kingdom would be in serious trouble, with the Mongol horde just a few provinces north of Jerusalem. But before the two armies could meet, it became clear that the internal council of the Tabriz Khanate was splintered and King Girard leapt at the chance to sign a white peace.

40,000 Mongols remained lodged in Hama, within the Kingdom, but a temporary truce was better then none at all.

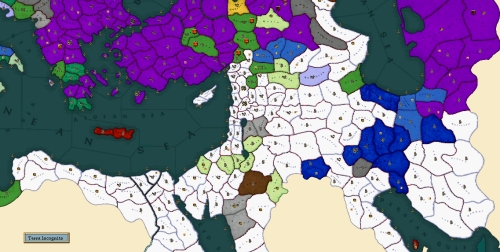

During the fighting, the huge Byzantine Empire to the north had taken the time to almost completely wipe out the Turkish enclaves in the middle of Anatolia. The Empire had reclaimed most of the land it had lost to the Turks.

In 1284 the small Archbishopric of Syria revolted, but that was only a precursor to worse news.

Not only had the island of Crete revolted, but King Girard had gained the 'Realm Duress' trait. Now he took penalties to several skills and all his vassals would like him even less.

This was bad, and in fact the trait would haunt him the rest of his life.

In the short term, however, the immediate problem of rebellious Crete could be solved by the application of 16,000 troops from Alexandria.

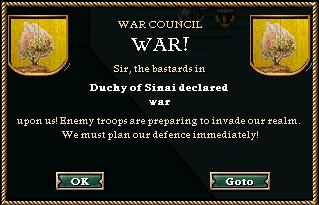

Yet troops had barely landed on the island before vastly worse news arrived. The Il-Khanate had attacked.

Although the Il-Khanate itself did not directly border the Kingdom, several of its vassals had recently gotten large numbers of fresh Mongolian troops.

King Girard raised the armies of the Kingdom and began to organize them for a defensive campaign against the Il-Khanate. In June, Crete swore it's loyalty again and the Alexandrian troops were shipped to the main land to resist the Mongols.

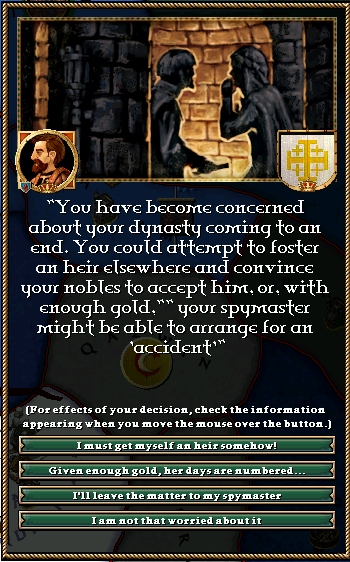

In July, as King Girard was getting ready to ride out at the head of his army, the Royal Spymaster came to him with a proposal to off his wife so he could remarry and have an heir, as he still lacked a legitimate son.

There was just one complication. His spymaster was his wife. He starred at her in disbelief. For 16,000 gold she was offering to commit suicide. King Girard explained to the woman that she couldn't take the gold to heaven, refused to give her a penny, and recommended she take matters into her own hands and do what she felt best.

She didn't kill herself.

The war against the Il-Khanate was a scrambled affair. In the north, King Girard left his vassals mostly to their own devices, and they seemed to do a pretty good job of holding off the Mongols, even if they lost a few border provinces.

Things might have gone very poorly for the Kingdom of Jerusalem but for two things. First, the Byzantine Empire asked to ally with the Kingdom and sent large numbers of troops down from the Russian steppes to harass the Il-Khanates northern flank. Second, there was a tenacious Turkish Emirate in Persia that, despite being reduced to a single province on multiple occasions, kept bouncing back and taking large swaths of provinces from the Il-Khanate.

King Girard simply helped where he could, dodging large concentrations of Mongolian troops, and stealing provinces out from behind them.

In the spring of 1286, while on campaign, King Girard added a new bastard to the two he already owned.

There were also several more revolts.

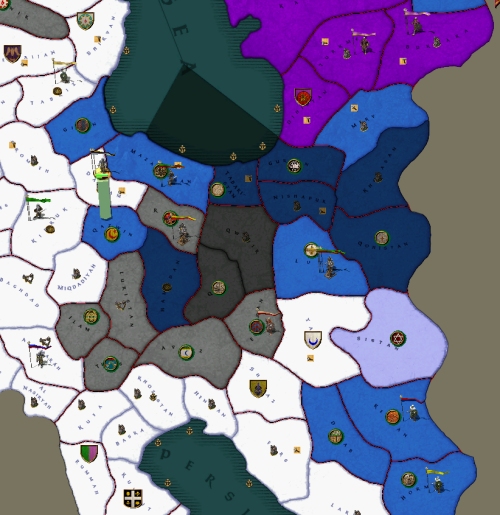

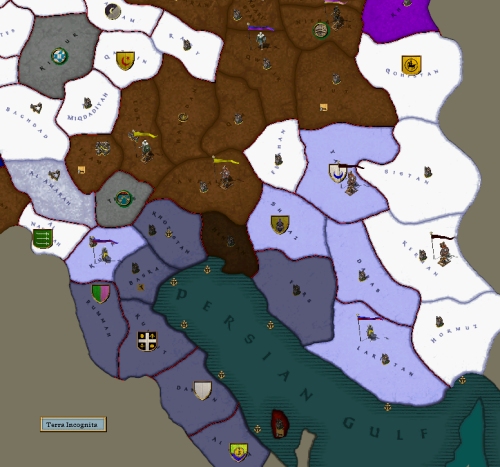

Although the Kingdom of Jerusalem had no formal relations with the Persian Turks, the two nations worked well together trying to roll back the Mongols. Here you can see the Turks in dark gray, and how their borders shifted over a period of a few months.

Back in Jerusalem, King Girard's wife told nasty rumors about him. As he was off on campaign, nothing much was ever done about this.

Early in 1287, soldiers of the Kingdom perfected the Longbow and put it to good use against the Mongols.

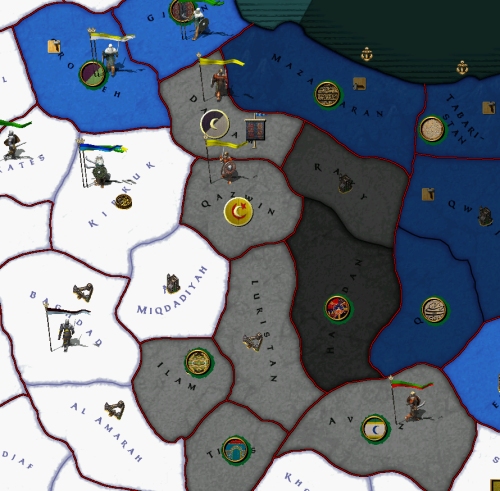

While the Byzantines were making great progress in the north, the plucky Turks were slowly being shoved back. But late in October of 1287, a large chunk of territory that the Il-Khanate had taken from them revolted and became a new Khanate, visible (barely) in dark blue.

The war dragged on for another two years, with provinces repeatedly swapping hands. The large duchy of Outrejourdain revolted, and King Girard reluctantly allowed it become independent, lacking the troops to suppress the revolt, having stripped Jerusalem and the heartland of all soldiers to fight the Mongols. Outrejourdain promptly swore loyalty to Navarra of all places.

Jaffa-Ascalon also revolted some time later, but reinforcements heading to the Mongolian front were able to suppress them.

King Girard's vassals thought it would be a clever idea to attack the breakway Khanate, which had also got swarms of fresh Mongols and it took several tries and surrendering a couple provinces to sign peace with them. During the process, King Girard gained the stressed trait. Who can blame him?

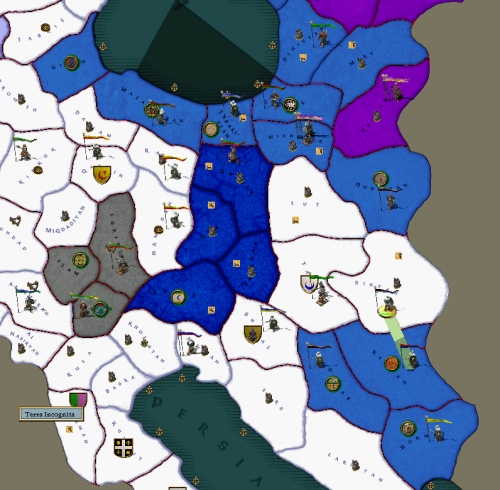

In 1290 peace was signed with the Il-Khanate.

You can see the Persian Turks have (again) been reduced to a single province. The breakaway Khanate is in dark blue and the Il-Khanate is in light blue, by the Caspain sea and also a few provinces above the KOJ. The light green is Navarran Outrejourdain. Crete, Damascus, and part of Arabia also went independent without giving me any choice or starting a war. These will eventually have to be reabsorbed.

King Girard couldn't jump into starting any wars, though. He may have made peace with the Mongols, but spends most of 1290 suppressing new attempts at Civil War in Jaffa-Ascalon (again) and eastern Persia.

Nor is he safe at home.

The Kingdom is almost out of debt when another 3000 is stolen from the treasury. It's starting to become clear that God hates Girard.

His wife dies in February of 1291. Damascus is revassalized in March.

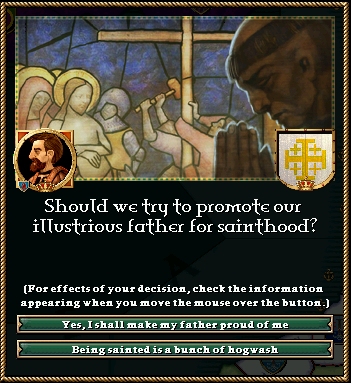

But in June there is, at last, a ray of sunshine for Jerusalem.

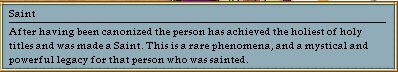

The dead Emperor Louis is officially made a Saint of the Catholic Church. St. Louis of Jerusalem.

Yet it is, at the same time, a sort of mockery by the Pope who still withholds the Imperial title from Girard. It should have passed to him, he should have been Emperor, but the Pope apparently thought otherwise, and continued to find excuses as to why Girard could not be crowned.

It's enough to make any man sad. Girard finally realizes that he will never live up to his father. He will never even be crowned Emperor.

The news of King Girard's melancholy is enough to make the timid ambitious.

Basra revolts near the end of the year (in pale blue, the dark brown is the changing Khanate). It is a rough struggle for King Girard, who is tired of fighting and whose armies, bled white by struggle, are driven back twice before they succeed.

Aleppo revolts. Then the Sini. Then Tripoli.

The are repressed, at great cost, and the Sini revolts again.

Damascus revolts. More of Arabia breaks away. The Kingdom sinks deeper into debt.

There is only one bit of good news. The Khan of the Il-Khanate has accepted Christ as his personal savior.

Not long after, King Girard ceases to be depressed. He should not have lost faith. If the Khan of the brutal Mongols can see the Light of God, then there is hope yet for the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Again and again, King Girard has ridden out to suppress countless revolts and invasions. Since the moment he became King he has done nothing but fight for his right to the title. His vassals may hate him, but none deny his bravery. Even though he is over sixty years old he still leads his knights in the vanguard.

In 1296 it costs him his life.

Riding north to suppress the revolting Duchy of Antioch his column of knights is ambushed.

No one at court is quick to send the ransom. For, in the end, no one loved King Girard.

No one at all.

His younger brother, the bastard son of King Louis who had, against all odds, had himself legitimized rides to Jerusalem and is made King Baldwin V.

The knight who secretly beheaded Girard is given pat on the back and little plot of land on Cyprus where he can live quietly and inconspicuously, having done his duty for the Kingdom well.

The body of King Girard who died, it is claimed, from the shame of being captured, is quietly buried with little ceremony. No one smiles publicly.

LONG LIVE KING BALDWIN V!