Part 49: The Looming of Fitna

Chapter 17 – The Looming of Fitna – 1648 to 16701648 was an inauspicious year, as the ascension of Utman to the crown of Al Andalus would forever change not just the Sultanate itself, but all of Iberia. Famously young, notoriously clever and assuredly capable, it seemed certain that the young king would rocket to dominate continental politics and carve his name into the very tablets of history, as his predecessors and ancestors had done in centuries past.

And indeed, his name would be remembered for quite some time, but not for any good reasons.

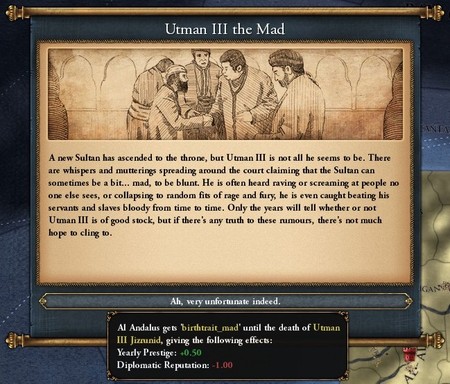

Utman was just nineteen years of age upon becoming Sultan, but he was already widely known for his zealotry, seen as a devout and pious man by his people. What was less widely known about the young sultan, however, were his occasional... fits.

Ever since boyhood, Utman had been headstrong and unruly, but as he grew older he began to exhibit more worrying characteristics. He would scream at apparitions no one else saw, threaten his ministers or viziers with execution for imagined slights, or even beat his slaves to death out of sheer paranoia. All of this made Utman erratic and unpredictable, not good traits to have in a Sultan.

After the highly-suspicious death of his elder brother whilst hunting, however, Utman was left as the only living son of Sultan Hafid. As planning for a grand coronation in Qadis was underway, however, guns were raised and blood spilt in the northern mountains of Iberia.

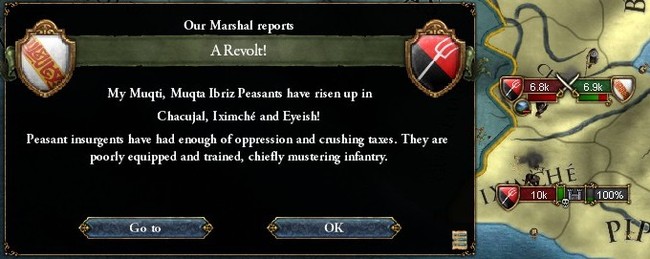

Towards the end of 1648, a string of uprisings and rebellions broke out in both the old world and the new. The Mubazirun army had been greatly weakened during the war with the Tlapanec Empire, but fortunately for the new sultan, Hafid had left the treasury overflowing before departing for the afterlife.

A massive mercenary army of 25,000 was thus raised, and once it had joined up with the remnants of the Mubazirun, the rebels were quickly destroyed in pitched battle.

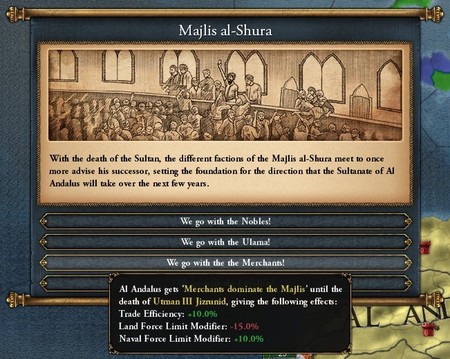

As the last of the revolts were suppressed, the coronation in Qadis finally came to an end, and Utman opened his first Majlis Assembly as Sultan. Despite a number of victories and accomplishments during their tenure, the mandate of the Majlis was torn away from the New Taifas, with the pompous silver-blooded merchants gaining a majority in their stead.

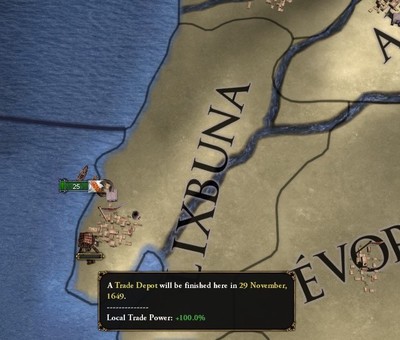

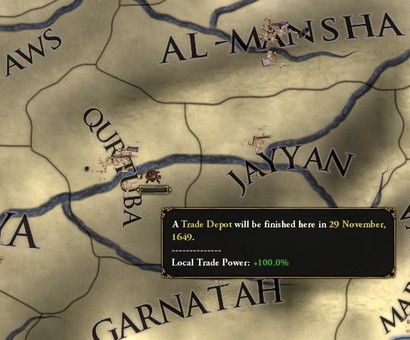

It had been decades since the Merchants had any real power, so they immediately began using their newfound influence to pass a number of bills making it compulsory for regional governors to construct trade depots, massive storehouses used to stockpile goods and merchandise.

The League of Merchants could no longer focus solely on trade and colonisation, however. The Taifas had waged war against Andalusi rivals for the past four decades, defeating and humiliating France in a series of decisive battles, and the northern powerhouse was sure to strike back before long.

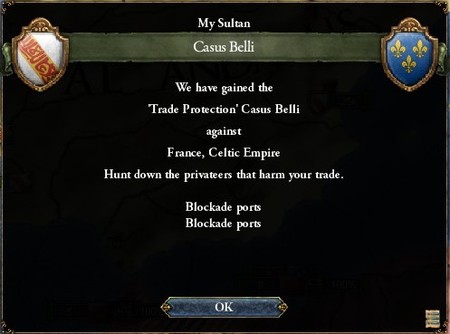

The French were still too weak to match Andalusia on the battlefield, however, so instead they resorted to privateering its merchant shipping. Iberia's rival on the seas, the Celtic Empire, also began seizing Andalusi goods and merchant vessels, infuriating many of the merchants seated in the Majlis.

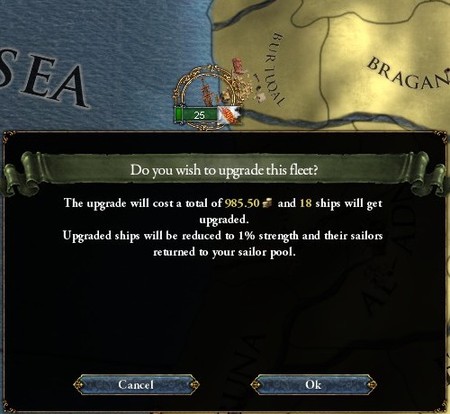

Hoping to counter the recent uptick in privateering, the Merchants spent a small fortune on upgrading the war fleet, outfitting the obsolete carracks and galleons with modern guns and better-trained officers.

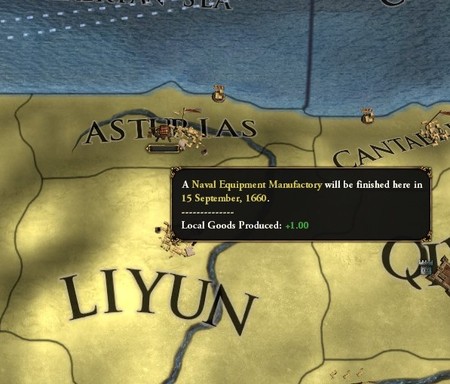

Most of these ships were essentially rebuilt over the next few years, with the outfitting largely done in the harbours of Asturias and Portugal, regions thick with the oaks and pine so essential to constructing warships.

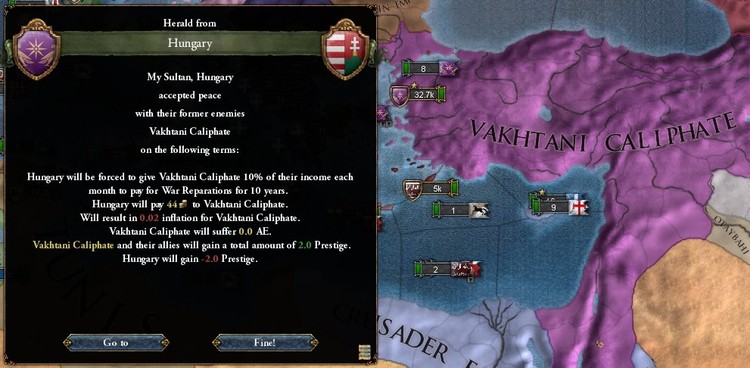

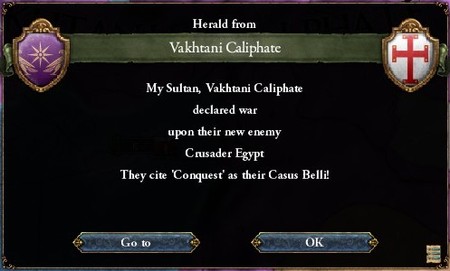

As tensions began rising between the powers of western Europe, a massive war in the east only just came to an end. For the second time in a decade, the Vakhtani Caliph managed to defeat a coalition of Balkan kingdoms on the battlefield, forcing them to recognise his conquests in Constantinople and Edirne.

Even with the Queen of Cities in his possession, however, the caliph’s appetite for war had not been sated. Within weeks of the Balkan War ending, the Armenian army began the march southward, with the Caliph himself declaring war on Crusader Egypt, vowing to capture Cairo and burn Alexandria.

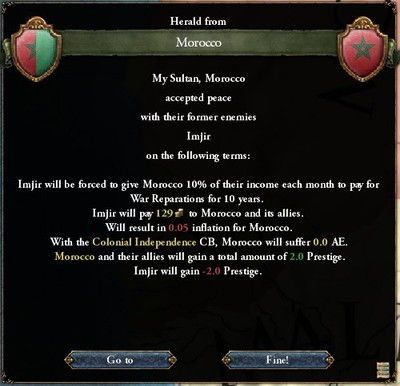

In North Africa, meanwhile, a war between Morocco and its colonies had quickly escalated when the Celtic High King intervened against Marrakesh. The conflict initially went badly for the Almoravid Sultan, but after sinking almost 30,000 Celts in a massive naval battle just off the Straits of Gibraltar, he managed to force the High King out of the war with a white peace.

With the bulk of enemy forces sunk, the war quickly turned in favour of the Almoravids. Successful naval invasions of both his Gharbian and Caribbean holdings were followed by a string of victorious battles, forcing the short-lived emirates of Imjir and Taghzir to surrender unconditionally.

And with that, the first independence wars in Gharbia come to an unsuccessful end, with Almoravid Morocco asserting its suzerainty.

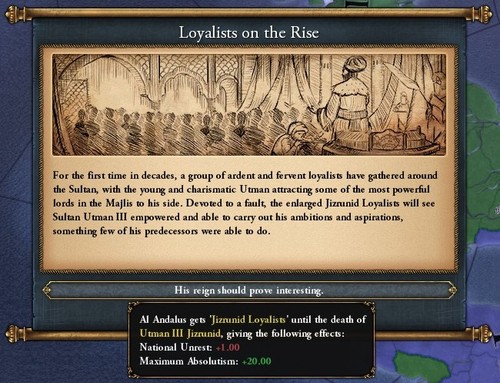

At the same time, back in the Andalusi capital of Qadis, the coronation of the new Sultan has sparked a flurry of excitement throughout his court. Utman III quickly became famous for his charisma and charm, his courage and intelligence, his devotion to his subjects and, above all, Allah. Before long, a large circle of dedicated followers began gathering around the sultan, consisting of some of the most powerful nobles and imams in the sultanate.

This did cause some panic in the Majlis, with some worried that the Sultan may use this influence to strike against his enemies in the assembly.

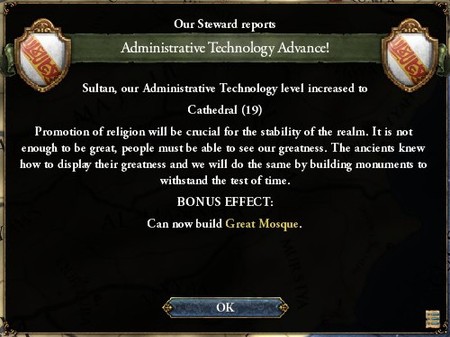

For now, however, Sultan Utman did nothing of the sort. Instead, he used his newfound friends in the Majlis to force a bill through the assembly, whereby monumental mosques would be constructed in all the largest and most important cities of Iberia.

Much like his father, he also funded the construction of a new university in Qurtubah, a city he favoured for its long and decorated history as the epicentre of Muslim Iberia.

Behind the scenes, however, Utman also began utilising a network of spies and missionaries to begin illegal conversion efforts. These efforts quickly bore fruit, with a number of cities becoming majority-Muslim within a few short years, including the Mediterranean island of Corsica.

And slowly but surely, he began acting against the Majlis’ policies of tolerance and acceptance, instead reversing course by issuing a number of edicts and fatwas that discriminated against the Dhimmi peoples of Iberia.

And it didn’t stop there, because from time to time, a strange… madness seemed to overcome the Sultan, and he would lash out without thinking. This resulted in countless scandals erupting in the royal court, especially after Utman ordered that the execution of a high-ranking vizier by burning at the stake.

By 1655, Sultan Utman had grown confident enough to proclaim himself the Khalifa of all Andalusi Muslims. This was seen as a foolhardy declaration by many, especially since no Iberian sultan had ever gone so far as to directly challenge the Vakhtani Caliphate before.

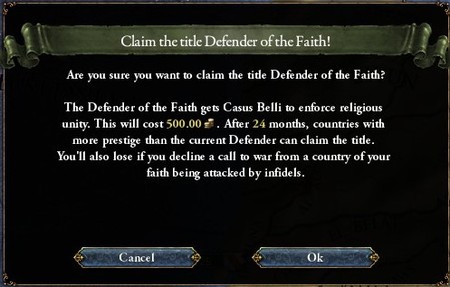

And in case the message wasn’t clear enough, Utman followed that up by declaring himself the Defender of the Faith and Commander of the Faithful, ridiculing the Vakhtanis as decadent pretenders in a fiery sermon to his loyalists.

Of course, these same fanatic loyalists immediately acclaimed the Sultan as their caliph, swearing fealty to him both in this world and the next.

Unfortunately for Utman, however, he was met with disappointment as his sudden declarations only caused a rift to grown between Al Andalus and its Muslim neighbours, none of whom recognised him as caliph.

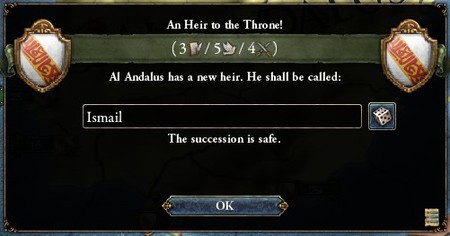

As a young man, however, Utman did have a number of pleasures to distract him from these failures. Like his predecessors, he regularly indulged in his large and varied harem, fathering a son late in 1657.

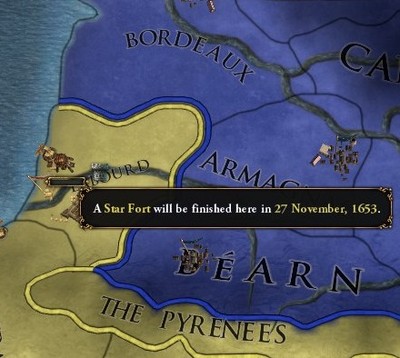

The Majlis, meanwhile, were occupied with actually trying to run the sultanate. After receiving word of French troops gathering near the border, the New Taifas convinced the rest of the assembly to invest money into further upgrading their border fortresses, with modern cavaliers constructed within the walls of Labourd and Roussillon.

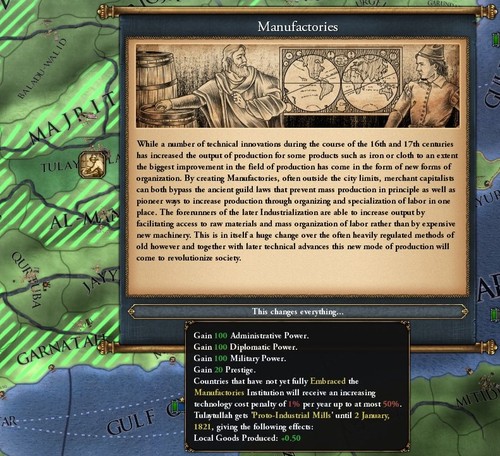

The Merchants used their dominance in the assembly to continue raising new manufactories, with regional Trade Stations popping up on the roads between all the major cities of Iberia.

In fact, this rapidly-expanding network of manufactories quickly resulted in the Iberian heartland becoming the epicenter of industry, not just within the peninsula but all across Europe. The population in and around Tulaytullah exploded as thousands migrated inland to find employment, further facilitating the expansion of industry as mills and machine tools became widely-used, all of which was supported by the Merchant-dominated Majlis.

All of these advancements came to a sudden halt less than a year later, however, as Sultan Utman once again struck without thinking.

Apparently displeased that his sultanate was so friendly with an ‘infidel republic’, Utman secretly sent a number of envoys to Provence, where they announced that the alliance between their two powers was now null and void.

This led to uproar in the Majlis, where the Merchants were especially infuriated by Utman’s transgressions. The Sultan stood firm, however, claiming that it was his divine right to rule without interference or intervention. The Majlis was nothing more than an advisory council, he insisted, only further angering the assembly.

Utman was no fool, however, and proved himself an adept politician as he quickly brought the crisis under control again. After the initial surge of anger had begun to ebb, the Sultan delivered a speech in which he claimed that internal division only strengthened their rivals.

Instead, they ought to focus on the future. So, knowing that it was precisely what the League of Merchants wanted, he announced that the time had come to expand in Gharbia, and bring the light of Islam to the heathen colonies and pagan natives.

The League of Merchants yearned for dominance in the new world above all else, determined to channel its trade straight back to Iberia. The Celts and French still had firm control over Panama and its environs, however, and thus controlled the narrow bridge that connected the two continents.

And so, in return for ensuring that the alliance with Provence was permanently severed, Sultan Utman agreed to sanction a war against the Celtic Empire. Once they were decisively crushed, he would then personally lead Andalusia in a war against France. That was Utman’s destiny, he was sure of it.

The Majlisi Merchants were in full support of the motion, so as war plans were quickly drawn up by the high command, the Mubazirun army was transported to Ibriz. Sultan Utman personally appointed a veteran general - Ugdada Yasmin - as the Supreme Commander of the Andalusi army, now a formidable force numbering almost 40,000 men.

And with that, Sultan Utman called another assembly of the Majlis, during which the Merchants used their majority to issue the long-awaited declaration of war.

The Celts’ allies in Brabant would flock to their defense, of course, but they were distant and relatively weak, so they shouldn’t pose much of a problem. The more prominent issue was New England, who were sure to intervene against any Andalusi aggression, worried about Muslim expansion in the new world.

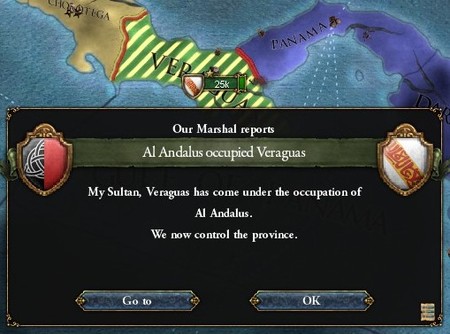

Supreme Commander Ugdada was convinced that the best way to win the war was to strike hard and fast, so even before the envoys had reached Dublin, he sent the Mubazirun surging across the border, quickly capturing the many Celtic settlements dotting Veraguas and establishing Andalusi garrisons in them.

While the war would largely be fought in Gharbia, a number of important battles did break out in Europe, with the Andalusi Fleet sailing northward and pinning down a large Celtic navy in the Channel.

The Andalusi had more warships and more guns, so the battle quickly turned into a one-sided contest, with more than twenty Celtic ships drifting towards the seabed by the time it'd come to an end. With that, the Andalusi managed to snatch early victories in both the old world and the new, handing them the initiative.

This unbeaten streak would not last very long, however, no longer than a few hours. Immediately after crushing the Celtic Navy, the Andalusi prepared to withdraw back to Iberian waters, only to be pinned down by another massive fleet.

The Celts have obviously been expanding their naval power over the past few years, because they now dwarfed Al Andalus on the seas, outnumbering them at least two to one. And so, after another hotly-contested battle, the Andalusi Fleet was forced to retreat en masse, leaving some of its prized capital ships behind to burn and sink.

Once news of the defeat reached Qadis, fears that the war would not be as easy as anticipated began to spread. How would they be able to safeguard the colonies, after all, if they couldn’t command dominance on the seas?

Back in Gharbia, meanwhile, the exiled English managed to coordinate a massive invasion of Andalusia’s northern colonies late in 1662.

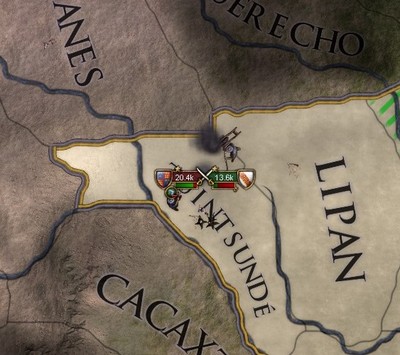

The Mubazirun were ferried northward by sea, quickly but carefully, anxious to avoid any Celtic ships. Once they’d landed on the northern continent, Commander Ugdada led them east to engage the English, with an engagement breaking out just two months later.

Not only were the English outnumbered, but they’d also foolishly attempted to wade through a deep tributary of the Mississippi, allowing the Andalusi to shoot at them from the safety of the bank.

The river was running red within minutes, but the English managed to make the crossing after fighting their way back up to solid ground, quickly reorganising their ranks as they did so. It took another three hours of heavy fighting before Ugdada could finally rout them, forcing them back across the water and scoring an important victory.

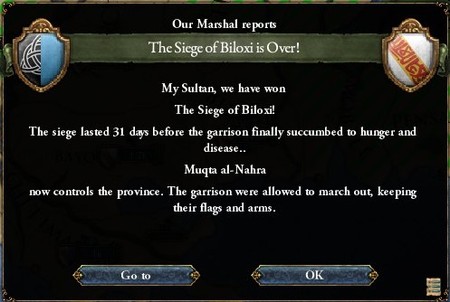

Once his forces were rested and recovered, Ugdada pushed east on another offensive, stopping only to recapture a strategic fortress which'd fallen to the Celts some weeks prior.

The English proved to be resilient foes, however, because scarcely another month had passed before they pushed across the border once again. This attack was sudden and unexpected, but Ugdada Yasmin managed to rally his troops and reinforce the battle, throwing the English back after a brief engagement.

Despite the victory, however, Ugdada couldn't ignore the fact that the Mubazirun were consistently taking heavier losses whenever they’d engaged the English. Losses they couldn’t afford to take, and it would only get worse.

So the Supreme Commander began planning for an invasion of New England, hoping to knock them out the war with a decisive offensive, only for bad news to arrive from the south.

Apparently, the Celts had landed a large expeditionary force in the Muqta of Ibriz, proceeding to capture vast stretches of rich land with almost no opposition. Sultan Utman personally intervened to order Ugdada Yasmin to throw them back, forcing the Commander to abandon his plans to invade New England.

Once all his troops had been ferried south again, Ugdada led the Mubazirun on a forced march, pushing towards the Celtic forces with all the haste he could muster.

Leaving behind a few small forces to recapture local towns and villages, the Mubazirun engaged the Celts in two separate battles early in 1664, utterly destroying the numerically-inferior armies.

There was no rest for Ugdada, however, because this was followed by news that the English had launched a third invasion of the Muqta al-Nahra. So once Ibriz was back under Andalusi control, the commander ventured north again, with his army quickly tiring from the endless hops across the Gulf, and pushed eastward to engage the English.

And third time’s the charm, as fate would have it. Ugdada engaged the English army with more men and more guns, but the English were able to employ far better tactics, hemorrhaging Andalusi cannons before crushing its centre in a brutal arcing maneuver.

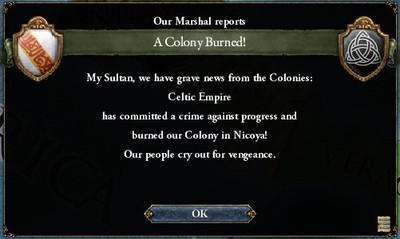

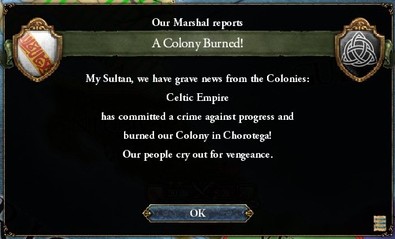

And with that, the Mubazirun were dealt a tremendous blow, forcing Ugdada to call from a hasty, chaotic retreat. Behind him, Andalusi colonies were quickly overrun by a mixture of English and Celtic troops, burning and pillaging with impunity.

An attempt by the Majlis to ship reinforcements across the Atlantic ended in abysmal failure after Celtic ships intercepted them, so Ugdada was forced to raise more mercenaries in the Yucatan peninsula, patching together another army numbering almost thirty thousand.

The two armies were roughly equal in number, but the English simply had better knowledge of the terrain and how to best use it, quickly destroying Mubazirun flanks and converging on its centre. The Andalusi were in full-blown retreat by sunset, leaving behind twice as many dead as the English.

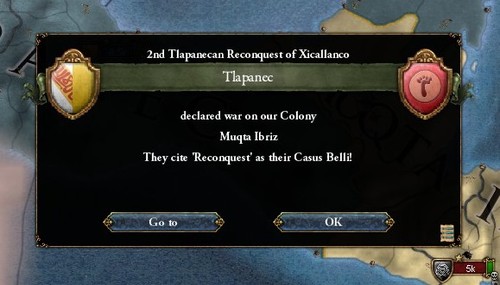

And with that second loss, only some 13,000 weary soldiers were left to the Mubazirun, out of the 40,000 who began the war. The utter destruction of the Andalusi army could only be good news to its rivals, and indeed, the Tlapanec Emperor pounced on the opportunity to devour Ibriz whilst its master was reeling.

This was quickly followed by the outbreak of a number of revolts throughout Andalusi Gharbia, conveniently interrupting any attempts to raise a new army.

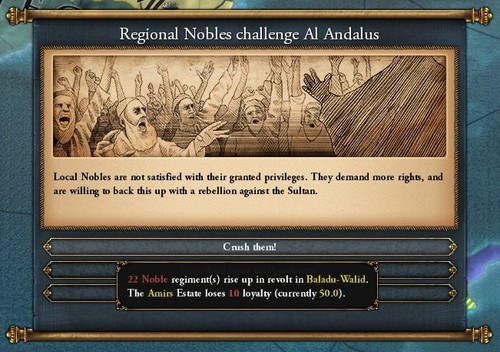

And as though that wasn’t enough, another crisis broke out in Iberia. Hoping to pounce whilst the Sultan and Majlis were distracted by their losses, a league of nobles rose up in revolt, demanding more autonomy in their home provinces.

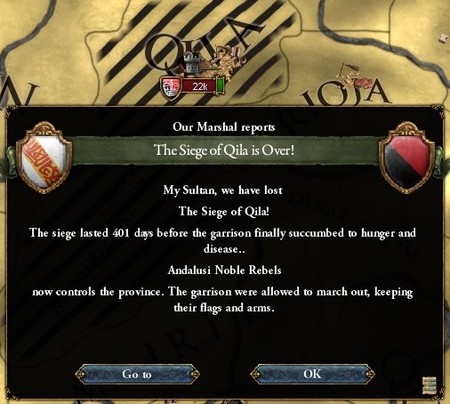

The rebellious nobles were led by Sheikh Musata Bilalid, who managed to raise a large army of disaffected veterans, marching them to capture the lightly-garrisoned fortress of Qila.

In Gharbia, meanwhile, the remnants of Ugdada Yasmin’s army were cornered at the very edges of Andalusi domains - beyond them, there was nothing but terra incognito. Refusing to surrender his men and arms, Ugdada forced the English to commit their forces to his last stand, holding them off for an impressively long time before being overwhelmed and killed in the ensuing slaughter.

With their Supreme Commander killed and the Mubazirun annihilated, the Majlis was all out of options, forced to send envoys to meet with Celtic diplomats. Sultan Utman angrily protested the surrender, delivering a sermon in which he criticised the weak-willed Majlis and accused its members of corruption and treason, but his words had no weight to them.

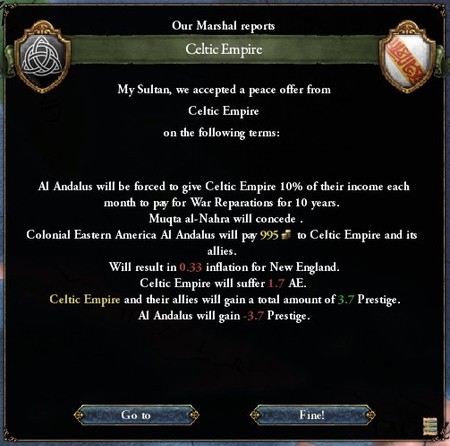

After a few weeks of heated negotiations, the war was finally brought to an end, with the Majlis agreeing to cede a narrow corridor of land to the Celts, along with massive war indemnities.

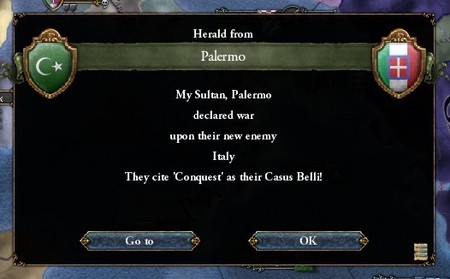

Whilst the Majlis were occupied with peace negotiations, another war had broken out in the east, with the Emir of Palermo marching an army into the Kingdom of Italy. An interesting development, but Andalusia had neither the time nor the resources to waste on Italian distractions, and attention soon turned back to the war with the Tlapanec Empire.

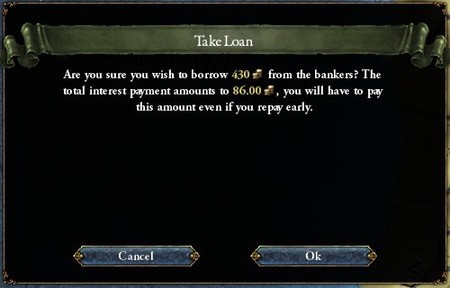

The Majlis were not so willing to surrender to the natives, they could not suffer that blow to their prestige. Before anything else could be done, however, the army had to be rebuilt. The treasury had been stretched thin by the war with the Celtic Empire, so the Majlis was forced to borrow large sums of money from local guilds in Qadis, promising repayment in the form of trade grants.

The gold was used to recruit levies that amounted to 15,000 men, with another 10,000 mercenaries reinforcing it. Sultan Utman insisted on personally leading the army, but the Majlis refused to placed him in such risk, instead appointing the veteran soldier Ya'far Hisham as the new Supreme Commander.

Ya'far was the son of an Andalusi trader and a Gharbian native, so it had taken his entire life to reach his heights, and he was desperate to prove himself worthy. So without wasting another day, he marched his army across Iberia, intent on crushing the noble's rebellion.

The sheikh put up firm resistance, but his army was smaller and scarcely-trained, so Ya’far was able to rout them without too much difficulty. Once the fighting came to an end, the sheikh was sent to Qadis, to be tried and executed at the pleasure of the Sultan.

Once Iberia was rid of rebels, the weakened Andalusi Fleet came into play once more, transporting the newly-built army across the great ocean. Docking at Ibriz a couple months later, Ya'far Hisham joined up with the remnants of the Mubazirun army, which had been similarly reinforced with mercenaries.

Together, the two armies managed to expel a number of smaller Tlapanec armies and push into enemy territory, quickly capturing large parts of the Yucatan peninsula.

The Tlapanec Emperor sent an army 35,000-strong to meet the Muslims, with a large battle breaking out in the dense jungle near the city of Tehuantepec. This would have ordinarily been a significant advantage to the natives, but Ya'far had been born in Gharbia, and he'd spent years fighting in these same jungles, so he was able to use his geographical knowledge to quickly turn the battle in favour of the Andalusi.

It took four hours of constant, heavy fighting to finally overcome the natives, but overcome they did. Ya’far managed to coordinate the two armies so that all escape routes out of the jungle were set with ambush parties, and once the Tlapanec army began breaking and fleeing, these parties leapt into action, slaughtering thousands of natives as they attempted to escape the battle and capturing thousands more as they tried to fight their way free.

The battle of Tehuantepec ended in stunning victory for Ya'far, with more than 30,000 natives dead or captured, and the route to Tlapan City wide open. The triumphant commander pushed northward with haste, his forces spreading out and capturing the lightly-defended villages and castles that paved the way to the capital.

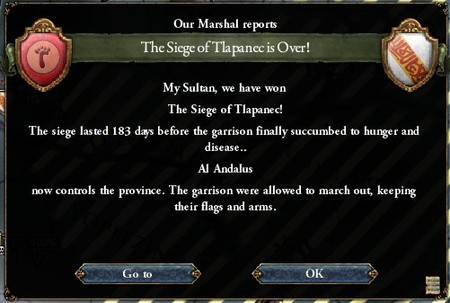

The Emperor attempted to flee upon hearing of the Andalusi victory and advance, but Ya'far sent scouting parties ranging miles ahead, forcing the emperor to fall back to his capital or risk being captured. Once the bulk of Andalusi forces arrived, Ya'far had Tlapan City surrounded and besieged, beginning the vicious bombardment its walls.

The city walls were old and badly-fortified, however, so it didn't take much to open a breach, through which thousands of Andalusi poured. Tlapan City was brutally sacked over the next few hours, with Ya'far personally leading the fight straight towards the citadel - screaming commands with guns in hand, blowing open its gates and capturing the Emperor himself.

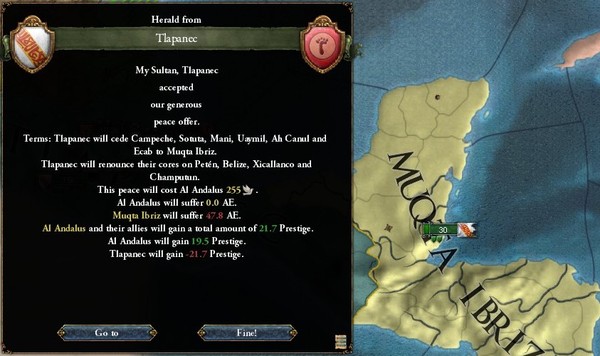

With the capital fallen and the emperor captured, the Tlapanec were forced to surrender to the demands of the Majlis, conceding the rest of the Yucatan peninsula and renouncing their claims on lost territories. The past two decades had been fraught with shocking reversals and humiliating losses, but this victory managed to bring the decline to an end, for a while at least.

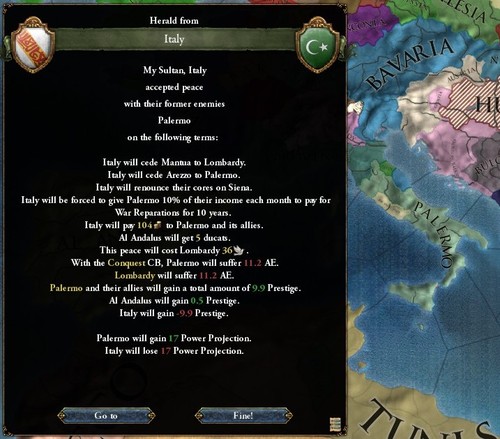

Back in the old world, meanwhile, the war between Palermo and Italy came to an end with a decisive victory for the Muslims. The ensuing peace treaty saw the Jizrunid Emir secure dominance over the entire Italian peninsula, something that seemed impossible mere decades ago.

Sultan Utman congratulated his distant cousin on his victories, though they only highlighted his own humiliations, further angering the Sultan. He had been stewing in his royal palaces for the past few months, forced to remain put by the Majlis, who were worried by his attempts to raise an army.

And of course, not a month of peace had passed before a string of Mayan rebellions broke out, with the city-states likely hoping to secure independence after a century of harsh Tlapanec rule.

No such luck, as Supreme Commander Ya’far was tasked with crushing the revolts, which he did with ease. And once the city-states were under his firm control, he managed to convince the Majlis to proclaim him the governor of the Yucatan, as a reward for his crushing victories during the war.

And how did the famous Ya’far Hisham thank the Majlis for these honours?

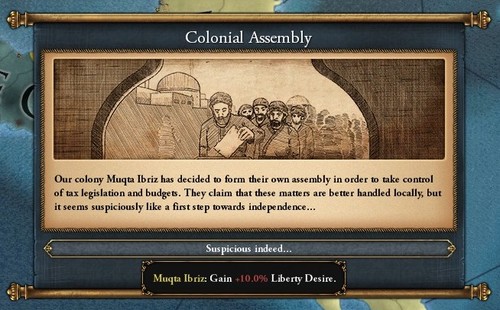

By meeting with the Muqti of Ibriz and forming a colonial assembly, in strict violation of Andalusi law. As Ya’far knew full well, however, the Majlis could do nothing about it. Not whilst they were so weak, and certainly not whilst Ya’far himself had the command and adoration of the army.

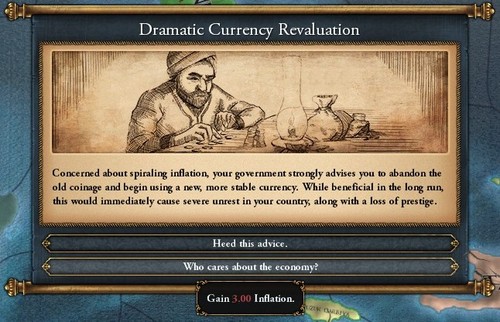

And the Majlis was certainly at a low point, both in power and authority. The loans taken out during the war, combined with the constant influx of gold from the new world, had resulted in a stark rise in inflation and added to the threat of an economic crisis breaking out.

Several members of the assembly quickly sought to take action against the rising inflation, hoping to abandon the Andalusi dinar and replace it with a newer, more stable currency.

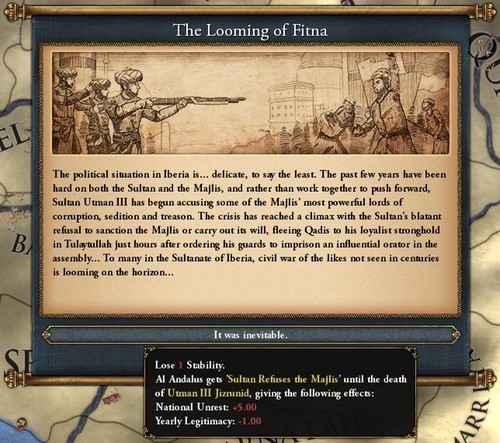

They were prevented from doing that, however, and by none other than Sultan Utman himself. Utman blamed the Majlis for the disastrous war against the Celtic Empire, and after they refused to let him raise and lead an army into war, he quickly began growing disillusioned with the whole concept of an assembly, certain that it was his divine destiny to rule as an absolute monarch.

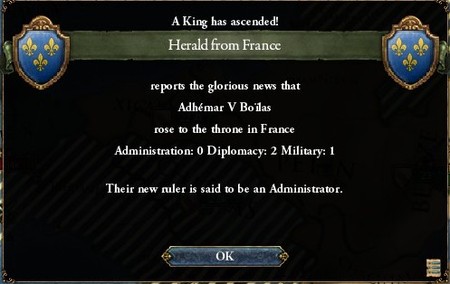

The inevitable clash between Sultan and Majlis finally came to a head a few weeks later, though it was sparked off by a foreign event: the ascension of the Italian Bo’ilas dynasty to the Kingdom of France.

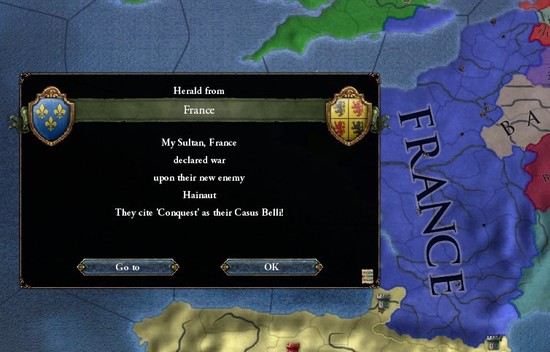

This new King Adhémar was young and ambitious, determined to begin his reign by throwing down the gauntlet, as it were. So he wasted no time in declaring war on the tiny principality of Hainut, only for another German coalition to flock to its defense and march on Paris.

As had become routine, the war quickly turned against France, and so the Majlis saw an opportunity to pounce. The Andalusi army was larger than France’s, their technology was superior, and France was stuck in a foolish war, this was certainly an opportunity.

Two factions in the assembly – the Taifas and the Ulema – formed a coalition with the intention of declaring war against France. Together, they had more than enough influence to counteract any opposition from the Merchants, and before long, plans to declare were underway.

But again, Sultan Utman stood against them.

In another heated speech, the sultan condemned the New Taifas as nothing more than fools, so intent on warring at any given opportunity, and the Ulema as traitors, to be so willing to war with their Muslim neighbours.

So Utman utterly refused to sanction the war, and when the Majlis tried to issue a declaration of war without him, he dissolved the assembly and ordered his guards to imprison several of its highest-ranking members. When this attempt failed, he fled north to Tulaytullah, vowing to return to the capital with an army.

In the space of a few months, the rift between the Sultan and Majlis has widened to cavernous depths, and now promises to tear the country in two. As fitna threatens to overwhelm the Sultanate, each and every noble, imam and merchant is facing a daunting choice – Sultan or Majlis?

World map: