Part 55: The Golden Age of Al Andalus, Part 1

Chapter 23 - The Golden Age of Al Andalus, Part 1 - 1728 to 1745The Iberia of 1728 is an Iberia on the rise. It sees the Sultanate of Al Andalus sweeping across the peninsula, once more dominant and once more ascendent. It is a hub of global traffic, with a trade network stretching from the golden cities of Gharbia in the west to the war-torn Holy Land in the east. It bears witness to the clash of ancient kingdoms as France stumbles in the north and the Almoravids soar in the south.

It has been said again and again, but for the first time in many long years, the future of Al Andalus is looking bright.

There was definitely an air of optimism in the many courts dotting Iberia, only for it to be tainted by the sudden death of Sultan Tariq - a figure much beloved for his victories on the battlefield. The poets say that Allah marked his entry into Heaven by sending a great trail of fire to light up the sky, visible all across the world.

And as everyone knows, comets are a sign of good things to come. Right?

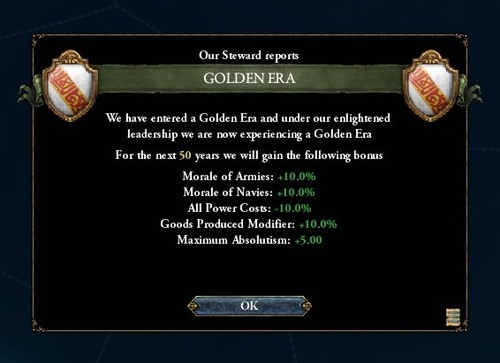

It wouldn’t be long before Al Andalus was back at its rightful place - the apex of the world. There was little doubt that the sultanate had fully recovered from the devastation of the past two centuries. It had, after all, cut down the stain that was Portugal and fully solidified its hold on Iberia. Recent wars had also shown all the world the superiority of the Andalusi army, the pride of the sultanate. Sultan Tariq had even orchestrated a revival in art and culture during his last days, spearheading the Enlightenment in Europe.

So surely it isn’t much of a surprise that some began to whisper of the dawn of a golden age for Al Andalus. A bit early to do so, perhaps, but the future was certainly radiant and hopeful.

This golden age began with the ascendence of a new sultan to lead the Jizrunids - both the Shia and Sunni branches.

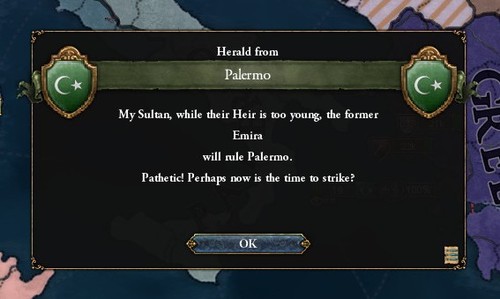

Halfway across the Mediterranean, the aging Emir of Palermo had followed his cousin across the sea into the afterlife. He left his emirate to his one-year-old son, though it would be the young emir’s mother who would lead Palermo until he came of age.

Similarly, after the sudden deaths of his uncle and father and brother, a one-year-old was also crowned in Al Andalus - Sultan Ali III, the first to really bear the name since the days of the Mad Sultan, almost four hundred years ago.

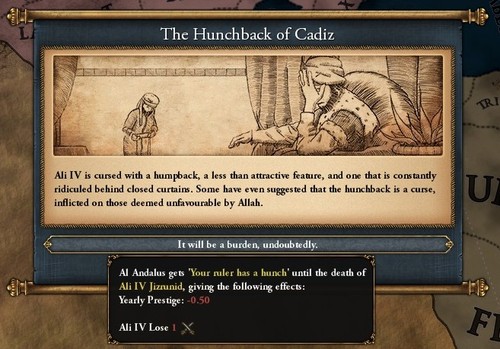

This new Sultan was not exactly a physical specimen, however. Unlike his father, who had been tall and strong even as a child, Ali had been born a hunchback, and this deformity would only worsen as he grew from a babe into a child and young man. To make matters worse, he would constantly be in pain and discomfort, surrounded by physicians day and night.

In addition to his deformity, Ali was still just a child, so he wasn’t fit to be named Sultan just yet. Unlike in Palermo, however, the Queen Mother did not become regent. Things didn’t work that way here, in Iberia.

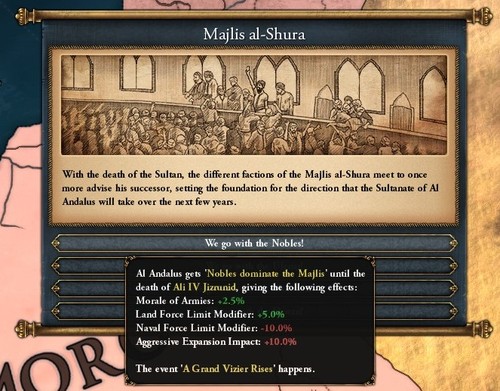

As dictated by the treaty that had ended the devastating Fitna of al-Andalus, it was the Majlis al-Shura who had supreme authority in the sultanate, and it was they who took the reigns during times of crisis or regency.

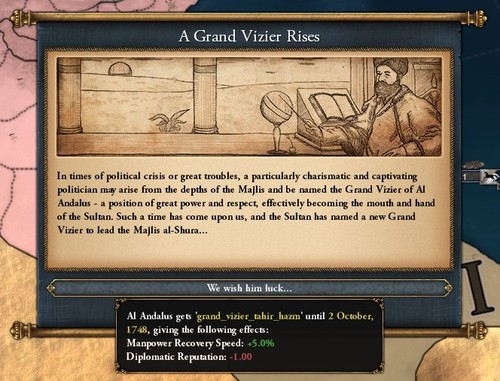

The entrenched aristocracy were still the largest and most powerful faction in the assembly, so it was one of them who rose to become Grand Vizier - a highly-coveted and powerful position, the man who served as the Sultan’s mouth and arm.

The nobles elected one Tahir Hazm ibn Yahaff to become their leader. Born the younger son of the Emir of Balansiyyah, Tahir’s quick wit and sharp tongue had helped him quickly rise to become one of the most powerful politicians in the Majlis, with his assertive stances on religion (he was of the opinion that Muslims shouldn’t have alliances with Christians) causing uproar more than once.

The new Grand Vizier immediately got to work by stemming the tide of painters, chroniclers, alchemists and inventors flowing into the royal court. Tahir saw it as a waste of good Andalusi coin, coin that would serve a far better purpose were it used elsewhere - such as, say, the army.

Of course, the bloated Jizrunid Diwan (the royal entourage) protested loudly and angrily, but they had no power to stop him.

That didn’t mean the Diwan didn’t have weight of their own, however, they still made up a considerable fraction of the Majlis. Indeed, through various forms of bribery and cajolement, they managed to pass a number of their own policies, including the construction of new roads, bridges, canals, prisons, parks, hospitals and schools all throughout Iberia.

Development mapmode: all provinces (except Mallorca) now have a development greater than 10.

They even managed to acquire funding for new universities in Tulaytullah and Granada, both highly-populous cities and both with strong symbolic links to the Jizrunid dynasty.

As a new age dawned in Al Andalus, the Almoravids of Morocco were continuing the rapid expansion of their colonial empire. A long, drawn-out war in India had finally come to a successful end, with Almoravindia now stretching from the Gulf of Gujarat in the north to island of Ceylon in the south.

The pride of the Almoravids seemed to have no end, however, because the Moroccan Sultan followed this up by declaring himself the Defender of Islam - a clear insult to his Andalusi rivals across the straits.

Determined to prove his worth as leader of the Muslim world, the Almoravid Sultan declared a series of wars in India and Indonesia, quickly absorbing the small princedoms of Bijapur, Sulu and Ternate into his global empire.

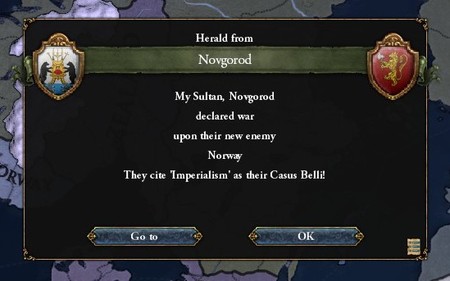

In the cold, icy wastelands of Russia, meanwhile, the Tsar of Novgorod had publicly claimed the throne of Cherson. Were he to inherit the kingdom, it would massively enlarge his own empire, which would surround his rivals in Smolensk on three different fronts.

His ambitions were not limited to becoming Emperor of All Russia, however, he was also determined to be seen as the lawful king of Sweden and Norway. Towards that end, he embarked on one final Scandinavian campaign, one which end with the defeat and conquest of the last independent Nordic state.

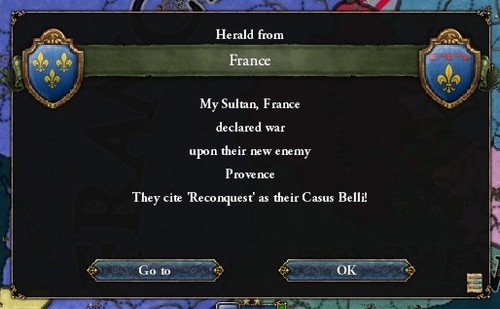

Closer to home, meanwhile, the French-Celtic War had come to an end with a stunning victory for the French. They’d not only reclaimed Brittany, but also forced the Celtic High King to cede vast stretches of land in the new world, not to mention a valuable port in Kent.

France, which had been a kingdom on the decline a mere decade ago, was suddenly stronger than ever. And they didn’t stop there, because the French king declared war on Provence mere weeks later, once again pitting east against west and thrusting the French against the combined armies of Provence, Bavaria and Liege.

These developments were worrying, to say the least. If the French managed to emerge from the war victorious, then they would look to the south next, to the fertile plains and populous cities of Al Andalus.

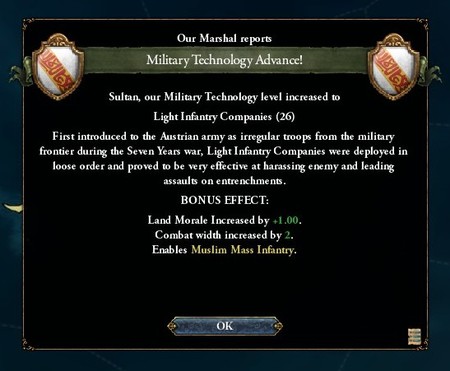

Led by Grand Vizier Tahir and the Taifas, the Majlis began focusing on further developing their standing forces. Not only was the Andalusi army enlarged to almost 80,000 men, but new tactics and weaponry was imported from Christian Europe, refitted so new recruits could be trained and drilled in their use.

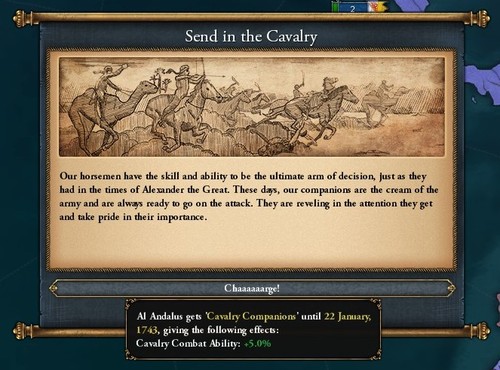

Huge investments were also put into the cavalry, which served important roles in scouting, support and battle itself, with cavalrymen trained in how to charge a line using whatever weapons were at hand, from lances to pistols.

One aspect of the military that was left overlooked, however, was the Andalusi Fleet. The merchants sitting in the Majlis tried to rouse support for the navy, but beyond constructing a few more Celtic threedeckers, little else was done.

Large parts of the Majlis, it would seem, had lost all interest in projecting naval power. Many saw any attempt to stay on par with the Celts (or even Moroccans) as a hopeless endeavour, and twenty heavy ships definitely wouldn’t be enough to wrest control of the seas, so the navy was left to slip into irrelevance.

Of course, this led to a rise in raids and smuggling endeavours, with the Sultanate losing hundreds of dinars worth of goods, but still nothing much was done to curb it.

Another worry on the horizon was the diverse religious landscape of Iberia - which ranged from Sunni Islam to Zikri heresy to Cathar Christianity. Many in the Majlis (primarily the Ulema) saw this as a weakness, utterly convinced that the heretics and heathens would rise up when Andalusia was at its weakest…

With the Ulema now a small and inconsequential faction, however, their protests roused little attention from the rest of the Majlis. Instead, the imams and muftis were forced to use their sway over the masses to whip up a frenzied hatred for both heretics and heathens, with riots breaking out in major cities every few days.

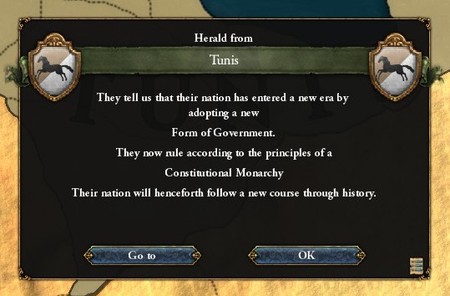

On a more encouraging note, meanwhile, there were a number of Muslim emirates who began adopting the Andalusi form of government over the Moroccan (which still took the Sultan’s word as absolute and divine).

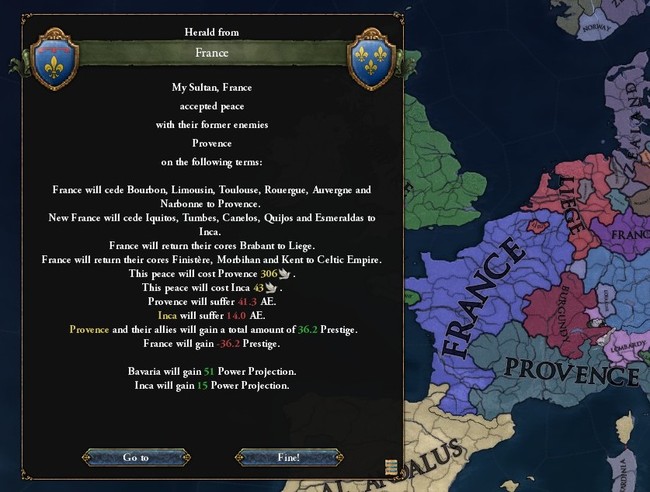

Back in the north, on the other hand, the war had seemingly turned against France. The French king had been forced to flee Paris as the Provencal and Bavarian armies advanced, leaving his capital to be sacked for the second time in as many decades.

His plan to somehow take on Europe single-handedly had obviously gone awry, and the French King was forced to sue for peace, with the negotiations set firmly in favour of his enemies. And indeed, when peace was declared a few weeks later, it was at the expense of some of his richest and most valuable land.

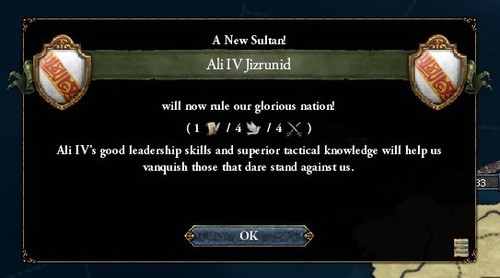

A weak France was certainly an attracting prospect, but the Andalusi had their sights set firmly on Qadis, where the young Sultan Ali III had finally reached his majority.

Ali wasn’t pretty or particularly clever, to his misfortune, and he was remarkably out of touch with his kingdom. In fact, Grand Vizier Tahir had purposely tutored him into becoming a gullible and rather soft-headed man, making it all the easier for the Majlis to keep their tight hold on Andalusia secure.

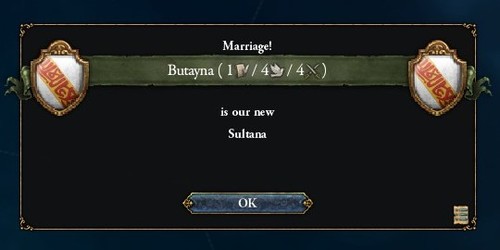

To that end, Tahir also arranged a marriage between the Sultan and a noblewoman, by the name of Butayna Abbadid.

Butayna was young and beautiful, but Vizier Tahir was far more interested in her name, and the weight it carried. The Abbadids were a very old and powerful family, ruling vast estates in Lishbuna and Baja, making them a very influential voice in the Majlis - one that Tahir was able to buy by marrying young Butayna into the royal dynasty.

And with their backing, the Taifas stood as one, with the entire world just waiting to be conquered.

In the north, the Celtic Empire took advantage of the opportunity to pounce on France, eager to reclaim Kent and Brittany.

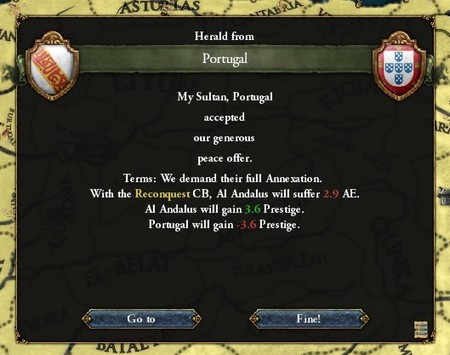

The Taifas, however, had their ambitions set closer to home. Portugal had been cut down to size in earlier wars, but they still ruled the small city of Bragança as a semi-independent entity, and that was an insult that couldn’t be allowed to stand.

Unfortunately, just days before the army was set to begin marching, the celebrated general Mundir Aliyah died in an unfortunate accident, breaking his neck after being thrown from the saddle. Grand Vizier Tahir personally awarded the commander with a grand tomb in Qadis, quickly appointing an equally-talented general named Ahmad Karima as the new Supreme Commander.

And once his control over Andalusi forces was secured, Karima led them into their first campaign in over a decade, armed with new weapons and trained in new tactics. They wouldn’t get much of a chance to test themselves, however, because the Portuguese surrendered en masse just minutes into the ensuing battle.

Karima immediately began the march towards Bragança, determined to test the new artillery, at the very least. But with the entirety of his army already in chains, the prince of Portugal was quick to surrender, giving up his city even before the first guns had blown.

And just like that, the war was over, lasting less than a month and costing some two hundred lives. The blight that was Portugal was finally wiped off the map, with Al Andalus stretching over the entirety of Iberia for the first time in over fifty years.

As far as Grand Vizier Tahir was concerned, however, the Iberian peninsula was the least of his ambitions. At the very next Majlis assembly, the Taifas began jostling for war with the native empires in the west (despite the fact that the Andalusi Fleet was outdated and outnumbered, and had no real presence on the seas).

Still, the natives were outdated in weaponry and outnumbered on land. Humbling them shouldn’t be too much of a problem.

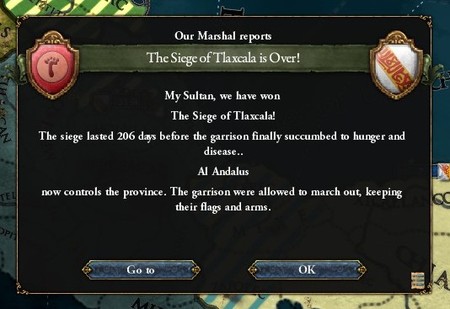

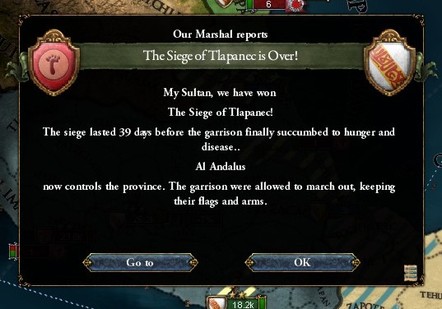

Grand Vizier Tahir sent a 40,000-strong expeditionary force to Gharbia, with the army disembarking at an Ibrizi port just before war was declared. In conjunction with colonial forces, Supreme Commander Karima surged across the Ibrizi-Aztec border mere days later, with another 20,000 Andalusi men attacking the Tlapanec Empire in the east.

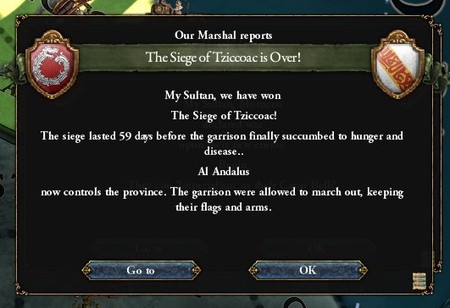

The natives were initially content to ravage southern Ibriz, but as the Andalusi pushed further south and threatened the Aztec capital of Tziccoac, the combined Nahua forces reversed course and attacked as one, hoping to dislodge the Andalusi and score an early victory.

This was Ahmad Karima’s first opportunity to use the tactics he’d spent years studying and innovating, and to his credit, they were very much a success. After almost three hours of heavy fighting in the thick jungle surrounding Tziccoac, the natives were forced to fall back with heavy losses.

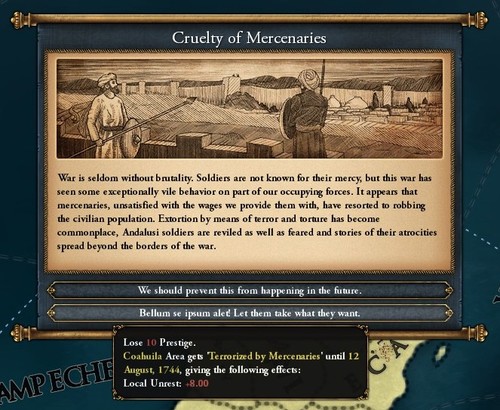

Karima then turned his guns on the Aztec capital, reducing its walls to rubble within hours, before leading his men into the city as they overcame the defenders and stormed the citadel, burning and looting and raping as they did so.

The sack of Tziccoac (also called the Aztec Sacking) would quickly become infamous all across Gharbia as thousands of men, women and children were all slaughtered without a second thought. Nobles and commoners alike were drawn up and hung in public, households was stripped of any valuables before its inhabitants were raped and butchered, half the city was afire before nightfall as nearby rivers and streams ran red with blood.

Situated across the Atlantic Ocean, it took months for news of the sacking to reach the Majlis, and even then nothing was done about it. It was a war, after all! What did people expect, that soldiers wouldn’t loot and rape? That homes wouldn’t be torched and holy temples desecrated? That innocents wouldn’t be slaughtered by the thousand?

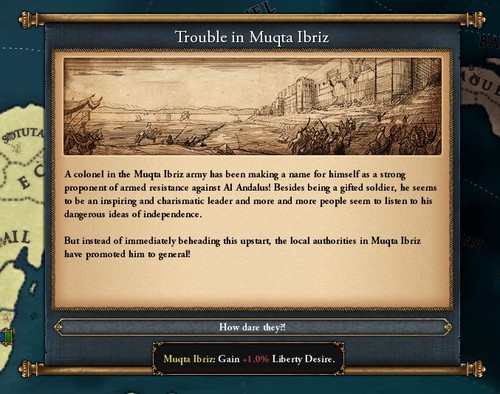

Unfortunately for the Majlis, the Hishami governors of Ibriz didn’t see eye-to-eye with them. Not only did they begin ignoring commands of the Majlis (even promoting a vile freedom fighter to general), but the Hishami went so far as to forbid the Andalusi army from setting foot in their territory. A bold move, considering they were subjects to Al Andalus.

Ahmad Karima, oblivious to the escalating conflict between overlord and subject, continued on his rampage by annihilating a native army in the battle of Tohancaen, taking no prisoners as he did so. The rest of the Tlapanec army pushed northwards and into Ibriz, where a colonial army was waiting to ambush them.

With that, the rest of the Tlapanec Empire was undefended and ripe for conquest, and the Andalusi army swept through field and city without mercy. From Tziccoac in the north to Tlapan in the south, farms and fields were burned to ashes, villages and towns were left vacant and smouldering, cities were ravaged for all their worth before being to put to the sword, there was no end to the carnage.

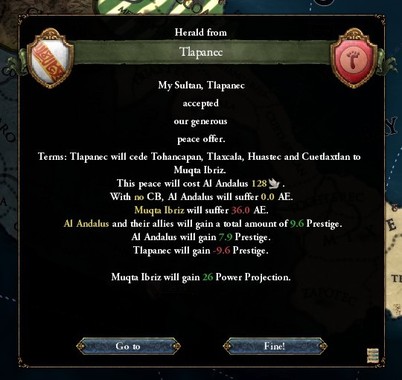

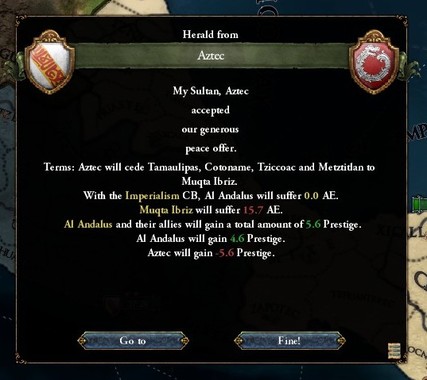

And by 1744, just a year into the war, the Aztec and Tlapanec Empires were on their knees. As always, the peace negotiations were heated and one-sided, with the Tlapanec Emperor forced to cede some of his richest and most fertile land.

Still, that was a kind fate compared to the Aztec Empire, which was conquered in its entirety. The Aztec emperor himself was executed, to ensure he wouldn’t start any trouble down the line.

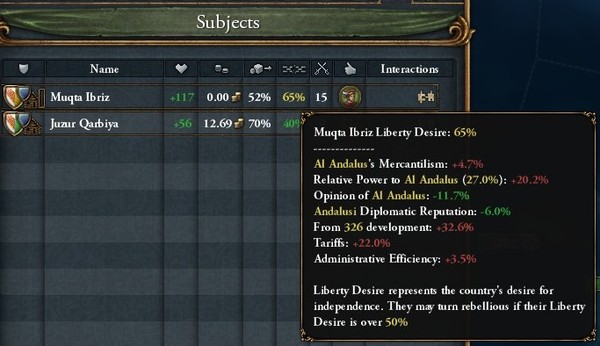

With that, the two halves that made up the Muqta of Ibriz were linked into one whole, with the massive colony now ranging from the icy plains in the north to the rich goldmines of the south. It was larger than most empires (certainly larger than Al Andalus), and with the population and riches to surely become a great power…

That must’ve been what went through the minds of the Hishami governors over those next few days.

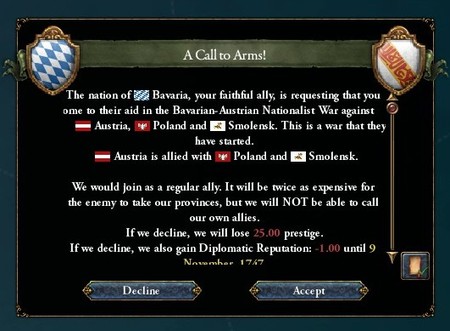

Back in Qadis, Bavarian diplomats arrived with a call-to-arms, hoping Andalusi forces would assist the Archduchy as it began a campaign against Austria. Grand Vizier Tahir was forced into accepting the call, but he refused to pledge any of his troops to a foolish war in the Balkans, not when tensions were already simmering in the west.

There had always been something of a rivalry between the governors of Ibriz and the sultans of Al Andalus, a rivalry that had gradually escalated ever since the Fitna had devastated Iberia. The Hishami governors had been granted autonomy from Qadis, but they still grew ever-more confident and powerful, refusing direct orders from the Sultan and Majlis, executing politicians and promoting traitors as they saw fit, even conducting independent raids and wars without authorisation.

That said, there would always be strains in the relationship between colony and overlord. Grand Vizier Tahir decided to settle for the more peaceful course of action: simply send a few diplomats to Ibriz, have them soothe relations between the two powers, and maybe remind the Hishami of their oaths and obligat-

Oh.

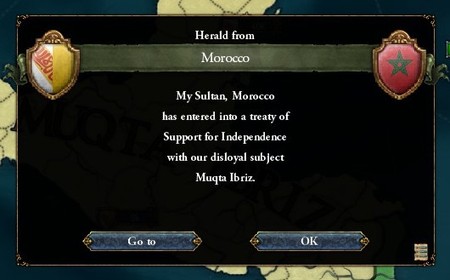

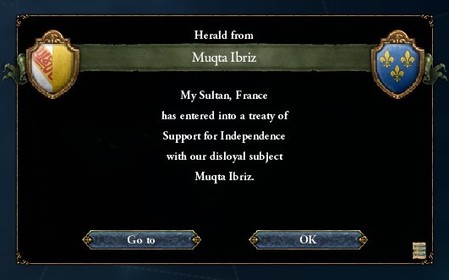

Shit.

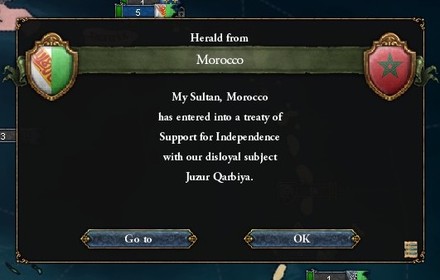

Alliances with Morocco and France, two of Andalusia’s oldest and fiercest allies? It seemed the Hishami were taking this all the way. Qadis quickly descended into anarchy as a thousand voices jostled and argued and screamed as to how they ought to proceed. Simply let the unrest die down? Try to repair relations anyways, hoping for the best? Demand that the Hishami cut off all these alliance without delay?

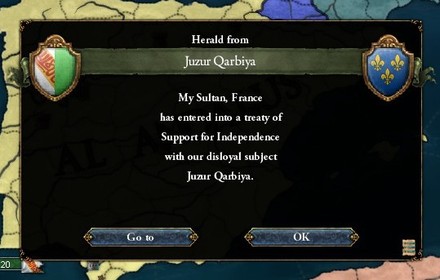

Whilst the Majlis were busy figuring out what to do next, Juzur Qarbiya (now little more than a lapdog to the Hishami) followed suite and formed official alliances with France and Morocco.

Needless to say, this wasn’t good news. Not good news at all. Something would have to be done as soon as possible, befo-

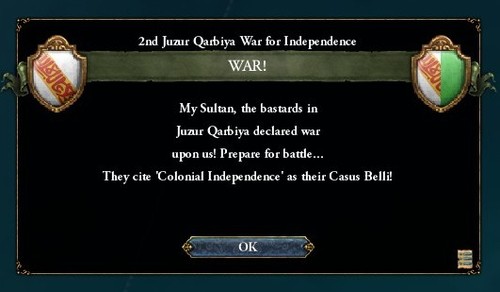

Before war was declared.

In the early months of 1745, a grand coronation was held in the capital of the Muqta of Ibriz, in which the Hishami governor crowned himself the "Sultan of Ibriz and all Muslim Gharbia". A grand title indeed, for an upjumped commoner with mixed heritage.

That upjumped commoner certainly had backbone, however, with the newly-declared Sultan denouncing the Majlis as an illegitimate and tyrannical force, and vowing to overthrow their rule in the west, with the aid of his allies in Morocco and France…

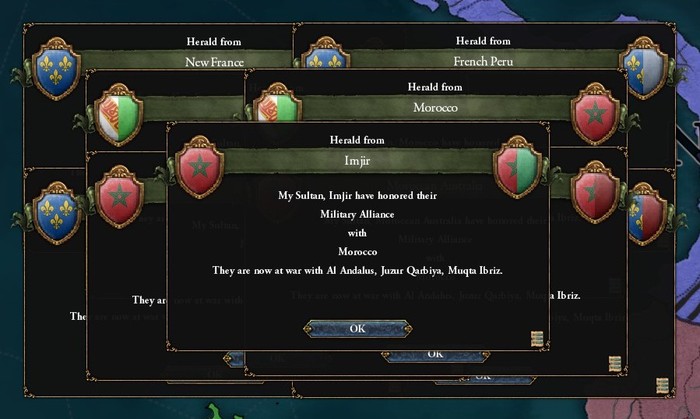

Along with all of their colonies too, for good measure.

With that, half of the world plunged into war, as the second bout of the Gharbian Revolutionary Wars began.

Al Andalus, Bavaria, Provence, Liege are all in a war against Austria, the Palatinate, Poland and Smolensk.

Al Andalus, Bavaria are in another war against Ibriz, Juzur Qarbiya, France, Morocco and all their respective colonies.