Part 58: Iberian Interregnum

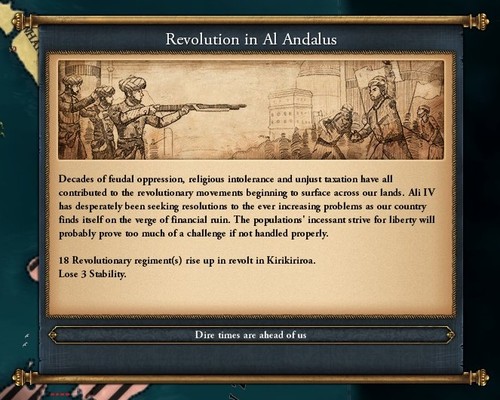

Chapter 26 - The Iberian Interregnum - 1762 to 1768The French in the north, the Majlis in the south. The fanatic zealots in Qurtubah, the Sunni Jizrunids in Tulaytullah. The Portuguese in the west, the Catalans in the east. The wildfire of rebellion that began with the Majlisi Revolt is quickly engulfing the rest of the Iberian peninsula, with Al Andalus itself being torn apart at the seams.

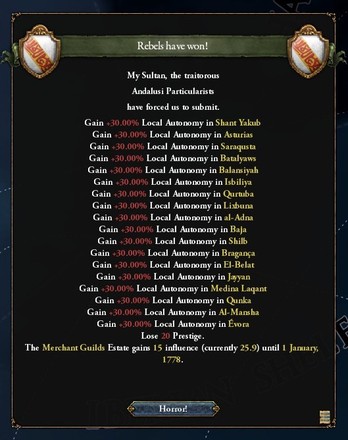

In all this chaos, the only man trying to keep his country in one piece was Wannaqo Ismail, now worn-out and jaded after years of fighting invaders, suppressing rebels and slaughtering innocents. He was still the Supreme Commander of the Andalusi army, or what was left of it, and he began 1762 with a campaign that stretched across southern Iberia, crushing particularists and noble rebels wherever he could find them.

The nobility were essentially in the same situation as the Sultan was, however, with almost no money or men to their name. Apart from the revolt in Catalonia, noble rebellions were usually limited to their cities and immediate environs.

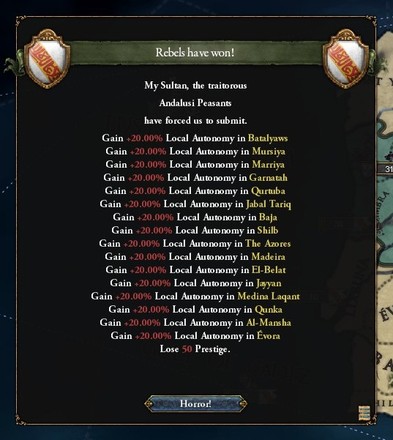

Posing a much bigger problem was, astonishingly, the peasantry. Adopting the ideals of the Bavarian Revolution, these peasants were sick and tired after centuries of fighting and dying for nobles, and were fanatically opposed to anyone who’d been born into money or power of any kind. Already, entire cities have gone up in flames as their local sheikhs were lynched without mercy, with thousands of peasants slaughtered as they did so.

It was already clear that these ideals wouldn’t be going away anytime soon, not so long as they had martyrs for their cause.

At the end of the day, however, they were still only peasants, with no experience in handling guns and no knowledge of battlefield tactics. Ismail Wannaqo cut through them like a knife through melted butter, killing and capturing almost 20,000 self-branded revolutionaries at the battle of Mursiya.

The ingenious commander followed this up with another victory in October, marching across the width of Iberia to engage a smaller revolutionary force in Baja. This army was actually led by a former noble who’d embraced the ideals of the Revolution, but the odds were still in favour of Wannaqo, and the battle could only end one way.

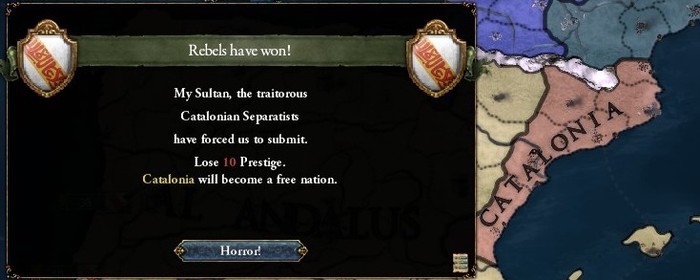

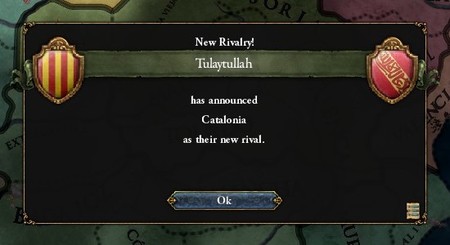

Unfortunately, for all his brilliance on the battlefield, Wannaqo could not be everywhere at once. Towards the end of the year, Muslim rebels had managed to overwhelm Andalusi garrisons in Catalonia and capture the regional capital. Beneath the soaring domes and towering minarets of Barcelona, the rebels crowned Abdul-Rahman Banu Saqq - a local noble who’d funded the revolt - as the Emir of Qattalunya, independent from Qadis and Al Andalus.

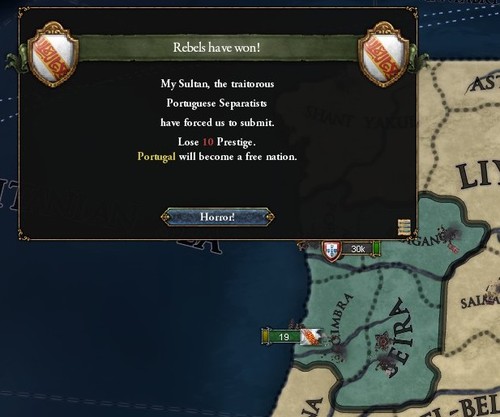

This was followed by another declaration of independence mere weeks later. Portuguese separatists had managed to capture large parts of northwestern Andalusia, and once their control over the region was solidified, they too crowned one Diego d’Alburquerque as the Prince of Portugal.

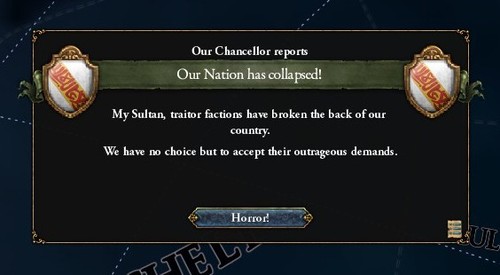

Now that large parts of Iberia were beginning to break away, the Majlis apparently felt the need to make a declaration of their own. In the bustling capital of Qadis, Grand Vizier Marzuq Aftasid proclaimed the end of Jizrunid rule over al-Andalus, and announced his intention to reclaim all of Iberia for the Majlis.

With that, for the first time in almost 700 unbroken years, the Jizrunid throne in Qadis sits empty.

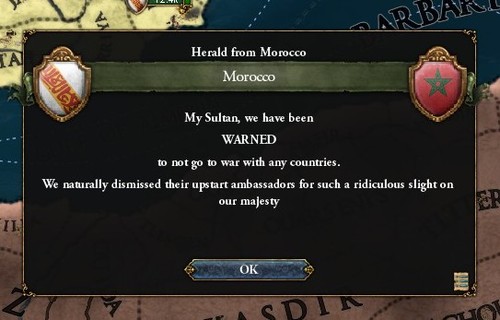

As though that weren’t sobering enough, the Moroccans wasted no time in taking advantage of all the chaos. From his capital in Marrakech, Sultan Agdun Almoravid sent envoys to Sultan Ali (who was holed up in Granada) warning him against any aggressive actions against the newly-independent states.

At the same time, the Berbers likely began planning an expedition of their own, hoping to carve out a piece of southern Iberia for themselves.

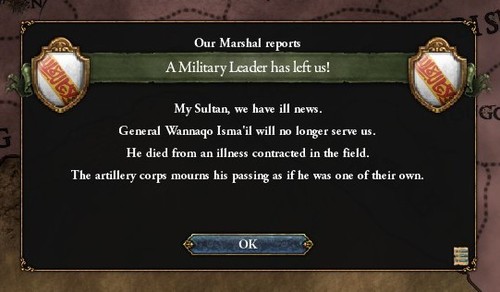

For Supreme Commander Ismail Wannaqo, this was the end of the line. Exhausted by endless enemies and corrupt officers, he led the remnants of the Andalusi army to the city of Mursiya, where he handed control over it to a junior commander.

Finally rid of his responsibilities and duties, Wannaqo himself wouldn’t be heard of for a very long time, with rumours saying that the famous general abandoned Iberia altogether, taking a ship to the island of Corsica. There, he was determined to live out the rest of his days in peace.

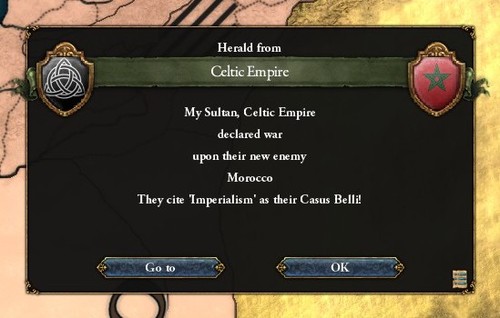

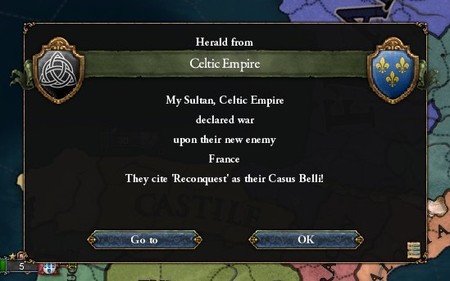

In the south, meanwhile, the Almoravids’ expansion plans were interrupted by their now-principal rival: the Celtic Empire. The young and ambitious High King Clemens was apparently ready to take on the full might of the Almoravid Empire, hoping to seize Berber possessions in Gharbia and India.

This would prove to be a foolish decision, however, because not even the Celts could fight a war against all of Gharbia. The past few months had already been spent embroiled in a costly war against Ibriz, the Andalusi colony-turned-empire, led by none other than the Hishami sultans.

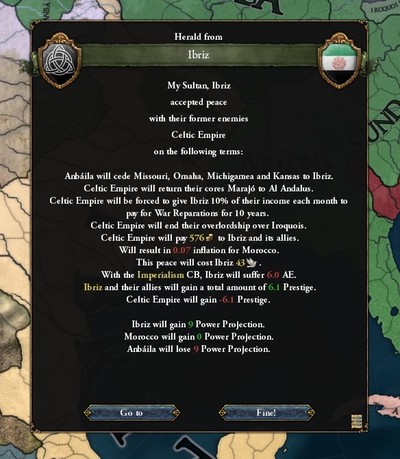

With the Celts’ resources now split between the Moroccans and the Ibrizi, the latter managed to launch an massive invasion of northern Gharbia, from which they emerged as the victors. With his possessions on the eastern seaboard now threatened, the High King was forced to sue for peace, ceding vast stretches of northern Gharbia to Ibriz.

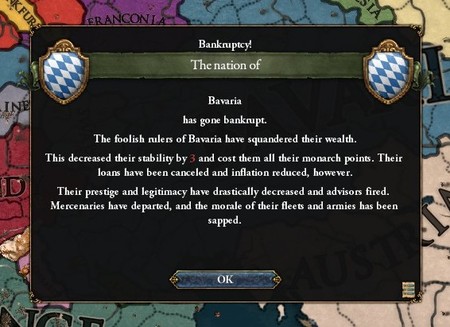

Back in the old world, meanwhile, things were not going well for the Archduke of Bavaria. Though he’d managed to maintain control over his largest and richest cities, defeating the revolutionaries in two separate engagements, it had come at a high cost - with the Archduchy declaring bankruptcy late in 1763.

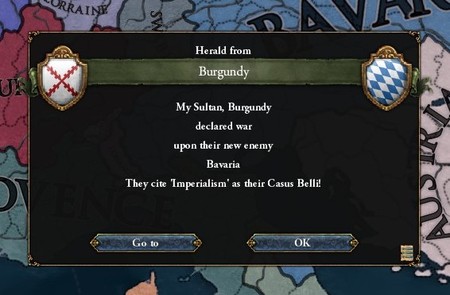

Opportunistic and ambitious, the Duke of Burgundy chose this moment to strike, declaring war on Bavaria and launching an invasion of his own.

Further east, tragedy struck the Tsardom of Novgorod as their young ruler died prematurely. With his younger brother still a mere child, the Tsarina swept into power as regent of the vast Russian empire.

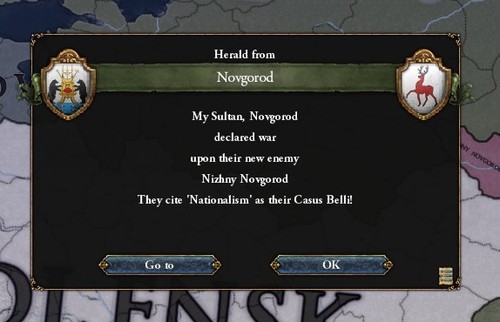

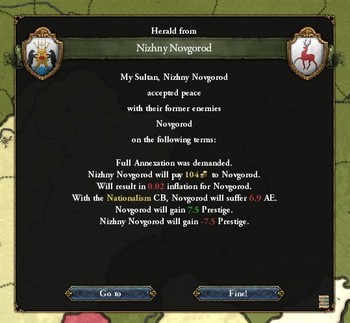

And she was just as ruthless and capable as her husband had been. Determined to see Novgorod become the dominant Russian empire, Tsarina Estafania used her influence as Queen Mother and regent to declare war on Nizhny Novgorod - the last Russian state separating Novgorod and Smolensk.

Needless to say, the tiny princedom didn’t pose much of a challenge to Tsardom of Novgorod, which now swept from Denmark to Siberia, unmatched in size and numbers. Even so, Novgorod was technologically and militarily behind their cousins in Smolensk, so the Tsarina began a wide-reaching program of modernisation, determined to emerge as one of the great powers of Europe.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, any control that Sultan Ali had managed to maintain over his cities was quickly collapsing into chaos. His governors were being overthrown and lynched in gruesome public executions, his walis were being run down and hung without mercy, word even reached him in Granada that his wife and son had been executed in Tulaytullah - charged with conspiring with the enemy.

Al Andalus itself was collapsing, and it seemed as though nobody was doing anything to prevent it.

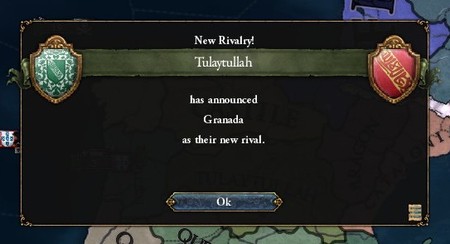

Speaking of Tulaytullah, Abdul-Qays - the Sunni claimant who’d seized control of the city - had managed to capture several important cities surrounding his new capital, seizing Majrit and Soria from Castilian separatists in two separate campaigns.

Having proven himself on the battlefield, Abd-al-Qays chose this moment to proclaim himself the one true Sultan of all Iberia, and the rightful head of the Jizrunid dynasty.

This was quickly followed by the Castilians breaking away from Qadis, further north. Large parts of ethnic Castilian land was still under the rule of the Andalusi, but this was the best they could do for now, restricted to the city of León and the mountainous towns dotting Asturias.

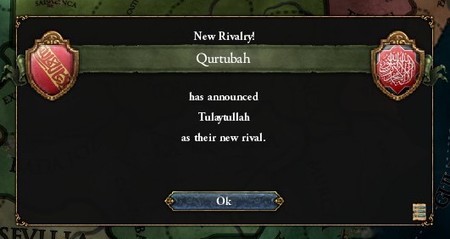

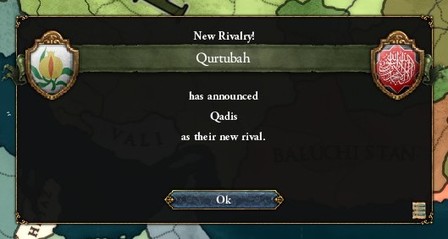

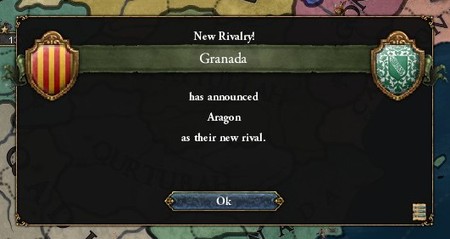

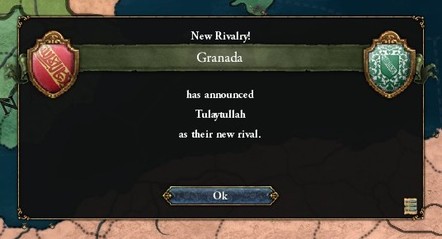

Of course, rivalries immediately began emerging between all these breakaway states, with bloody assaults and cross-border raids quickly becoming commonplace.

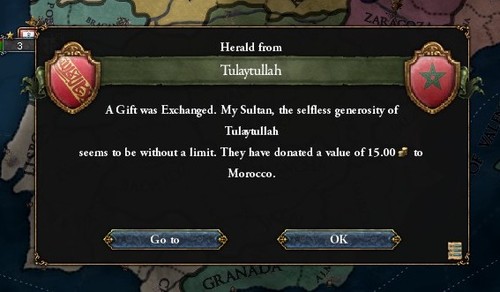

And obviously, the foreign powers surrounding Iberia didn’t just observe all the chaos as it unfolded, they began picking sides and funding their allies, determined to see their puppet kings rise to rule the peninsula. This game of influence began with emissaries and gifts being exchanged between Tulaytullah and Marrakesh, with the Almoravid Sultan bent on seeing Sunni Islam become dominant in Iberia once more.

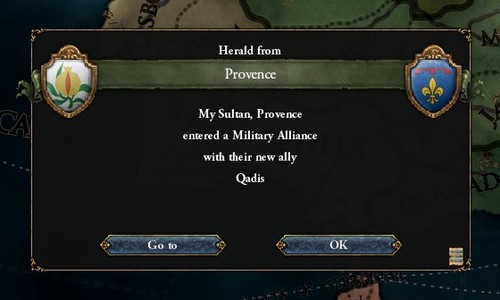

At the same time, the Grand Vizier and the Majlis managed to hammer out a pact with the King of Provence, promising to serve his interests in return for war subsidies and a defensive alliance.

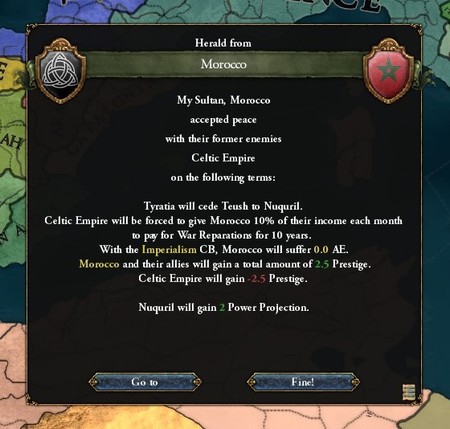

In the south, meanwhile, the war between the Celtic Empire and Morocco finally came to an end. Having already been bloodied by Ibriz, the Celts were unable to salvage anything from the war, forced to settle for what was essentially a white peace, save for a few minor border alterations in Gharbia.

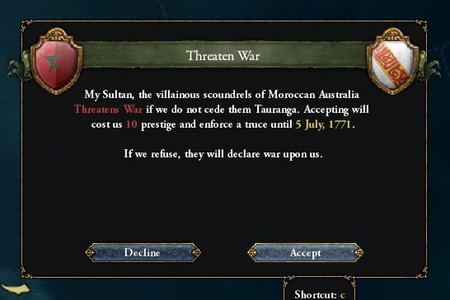

Now that he could focus his full attention and resources on Iberia, Sultan Agdun chose this moment to threaten Sultan Ali with war, demanding complete control of the island of Aotearoa, halfway across the world. The Mad Hunchback, who had neither the means nor the will to resist, simply surrendered.

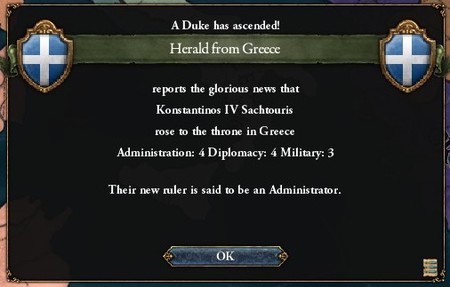

Across the Mediterranean, meanwhile, a talented young king rose to the throne of Greece. Konstantinos IV had ambitions on the Vakhtani Caliphate, seeking to recapture Constantinople and throw the Armenians out of Europe altogether.

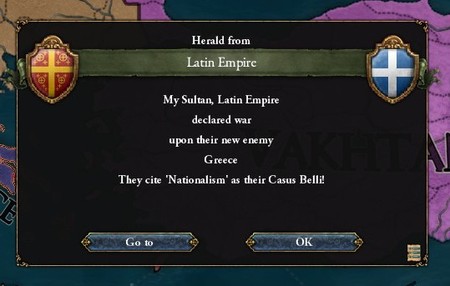

These ambitions did not get off to a good start, however, with the kingdom of Greece somehow losing a war against Serbia - a much smaller and weaker Balkan principality. And Konstantinos’ troubles didn’t end there, unfortunately, with the Catholic Latin Empire declaring war a few months later.

In the Middle East, meanwhile, formerly-static borders were suddenly and quickly being redrawn - and not in favour of the Muslim faithful.

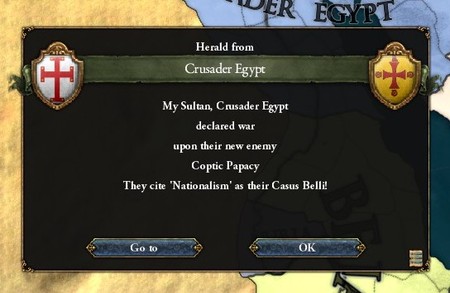

After decades of stalemate between Crusader Egypt and the Vakhtani Caliphate, the Sahidic-Egyptians had managed to take advantage of internal turmoil and launch a devastating invasion of the Armenian Empire, seizing large parts of the Levant and even threatening Anatolia.

With their fortunes on the rise, the Catholics began looking at expansion in all directions - with their prime targets being Baghdad in the east and the Hejaz in the south. The Crusaders began by declaring a series of war in eastern Africa, however, hoping to find the source of the Nile and use it to fund further expansion in Asia.

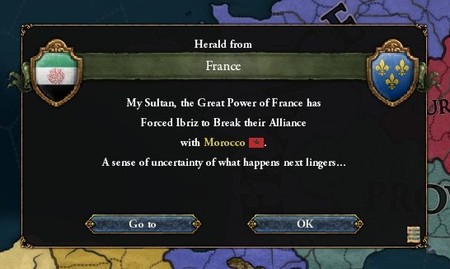

Much of the same was happening in the west, where King Aton had only recently emerged from a successful war against Al Andalus. That obviously wasn’t enough to sate the ambitions of the young French king, however, because his gaze turned westward soon afterwards, where he demanded that Ibriz break off their pacts with Morocco.

This Hishami Sultan, fearing another drawn-out and costly war with a European powerhouse, chose to comply with French demands, severing his alliance and trade deals with the Almoravids.

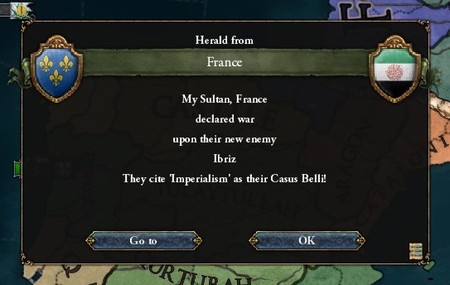

This quickly proved to be a foolish decision, however, with thousands of Frenchmen pouring across the border in Central Gharbia just months later as King Aton declared a colonial war.

Ibriz seemed to have garnered the favour of Allah, however, because the winds of fortune began blowing in their favour once again.

High King Clemens, having been humiliated in two successive wars, was determined to seize a victory somewhere, anywhere. For reasons known only to himself, he chose France as his target, declaring war on King Aton a few days after the French-Ibrizi conflict had broken out.

The decision to bring war to shores mystifies generals and historians even today, the Celtic Empire simply couldn’t match France in manpower or money, militarily dwarfed by their rivals across the Channel.

The Celts were superior to the French in one thing only - their navy, predictably. Massive Celtic threedeckers began patrolling French coasts upon the declaration of war, stranding any troops intended for Gharbia in Europe. This played right into the hands of Ibriz, with the Andalusi quickly overwhelming French colonial garrisons and pouring into southern Gharbia.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, the last of the breakaway states finally managed to assert their independence. Led by their so-called "Mahdi", a nameless and faceless imam who'd risen to dominate the Ulema, the clergy and their fanatic Sunni masses had managed to carve out a large slice of central Iberia for themselves, ruled from the holy city of Qurtubah.

And with their control over the region quickly solidified, the Ulema began a campaign of terror against any non-Muslims in their territory, with tens of thousands of refugees fleeing into surrounding principalities over the next few months.

With that, needless to say, any remnants of al-Andalus was gone and dusted. Thus ends 700 years of unbroken Jizrunid dominance in Iberia, 500 of which had been spent as the Sultans of al-Andalus, years which are quickly becoming nothing but a memory.

Sultan Ali - the Mad Hunchback - had only grown madder as the work of his ancestors collapsed before his very eyes, and at this point, no one can really blame him. Decrepit and depressed, Ali controls nothing more than a stretch of land lining eastern Iberia, ruled from the traditional Shia stronghold of Granada.

Inevitably, rivalries quickly broke out between the many neighbouring states, all of which were vehemently opposed to one another, with raids and forays becoming a daily occurrence. That said, having only just broken free after decades of rebellion and resistance, the daughter principalities of al-Andalus were still far too weak to engage in open warfare, so a lengthy period of desperate reconstruction and recruitment began…

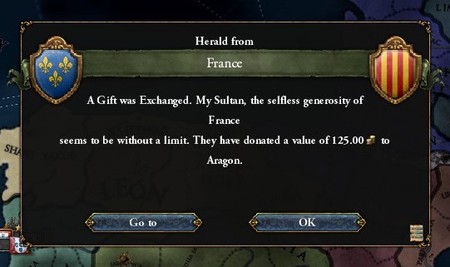

And of course, foreign powers wasted no time in interfering, with King Aton quick to announce his backing of the Prince of Aragon - favouring him with gifts and soldiers. And before long, Aragon became a willing vassal to Aton, with Aton no doubt hoping to see it become the dominant principality in northern Iberia.

Already working towards that end, King Aton warned the Emir of Catalonia against any expansion, especially against Aragon.

The French weren’t the only power with interests in Iberia, however, and the Moroccans stepped in shortly afterwards. Determined to stymie the French advance into the peninsula, the Almoravid Sultan guaranteed the independence of Catalonia, signing a defensive pact with the young emirate.

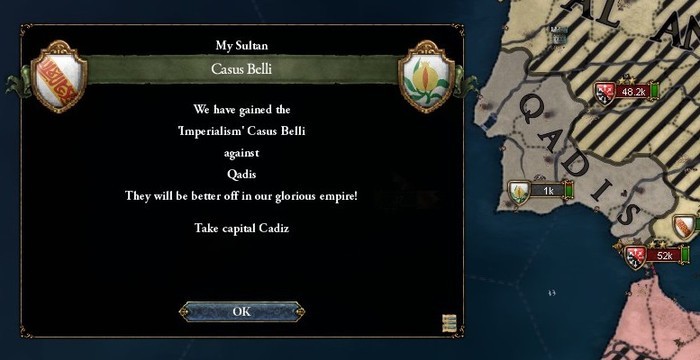

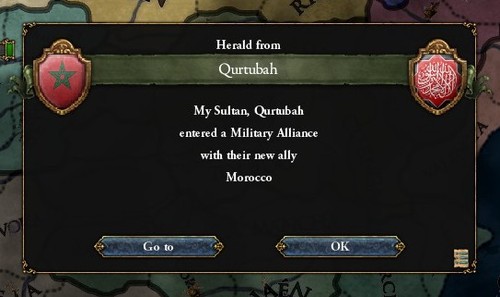

The Moroccans didn’t stop there, however - Sultan Agdun’s primary aim was to keep Iberia divided and chaotic, playing off the different principalities against one another. He already had ties with Tulaytullah and Qattalun (Catalonia), and to those he added an alliance with the fanatic Mahdi in Qurtubah.

Indeed, the only breakaway Andalusi states that Agdun wasn’t willing to negotiate with was Qadis and Granada, the former for their strange and dangerous form of governance, and the latter for their heretic Shia beliefs.

And with that, as 1768 comes to a close, Iberia is more divided than ever before. The utter collapse of Al Andalus has left a void on the world stage, and unless these minor principalities manage to emerge from the gutter and piece the peninsula back together, this may well be the funeral of the Gem of the Muslim World.

World map: