Part 60: Revolution is Here

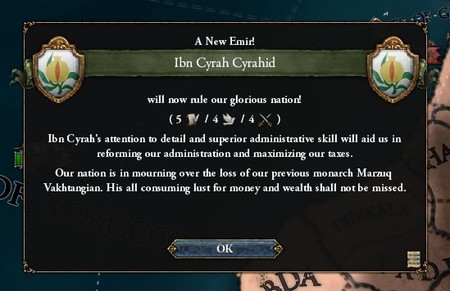

Chapter 28 - Revolution is Here - 1775 to 1786As the eighteenth century draws to a close and the world teeters on the edge of revolution, a new Grand Vizier is named leader of the Majlis and first governor of Qadis, along with all its territories and possessions. Ibn Cyrah accepted the ceremonial crown and sceptre after a lavish ceremony in the palaces of the deposed Jizrunid sultans, where he delivered a heated speech in which he vowed to see the fortunes of Qadis rise once more.

Ibn Cyrah was no newcomer to Qadisian politics, however, not by a long shot. Already an elderly man, he had been one of the prime instigators in the Majlisi Revolt that had overthrown the Jizrunid dynasty, he was responsible for the capture of Qadis and purge of its loyalists, and he had helped supplant the doddering fool Marzuq right up until his death. By all accounts, Ibn Cyrah had already lived a long and prominent life.

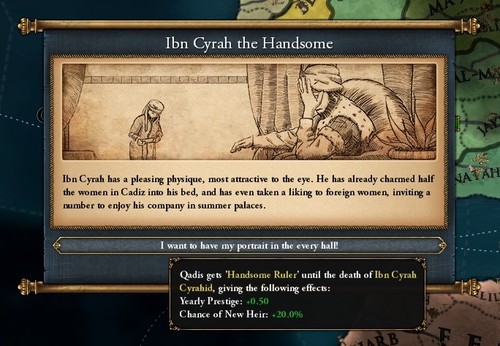

Even as an old man, Cyrah had a certain charm about him, beyond mere niceties and manners. He was a good-looking man, still strong and athletic, and certainly not behind on the latest fashions.

So it isn’t much of a surprise to discover that Ibn Cyrah already had dozens of bastards running about Qadis by the time he became Grand Vizier. No trueborn sons, though, he had never married. Now that he was leading a nation, however, the vizier was forced to follow custom and take official wives, carefully picked in an attempt to forge new alliances with nobles in the assembly.

Many of these attempts were quickly rebuffed, however. Ibn Cyrah was the sheikh of Niebla, and his ambition had certainly taken him to high stations - but he was not truly a noble, not in the same way the Aftasids were, or the Abbadids, or the Yahaffids - these were all names that had true weight, names that stretched back centuries, names with power and gold behind them.

Ibn Cyrah, on the other hand, was the grandson of a opportunistic merchant and his farmer wife.

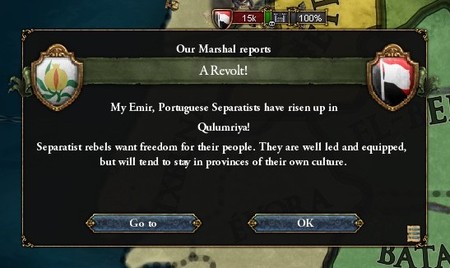

The new Grand Vizier didn’t have much time to react to the insulting refutes to his marriage proposals, however. Late in 1775, a large Portuguese uprising broke out in Qulumriya, with the unruly peasants desperate to break free and reform the recently-absorbed Principality of Portugal.

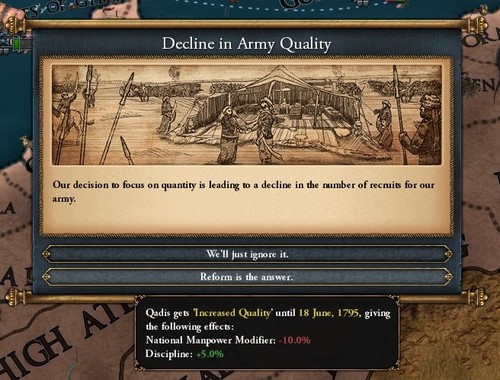

This was Ibn Cyrah’s first opportunity to prove himself as a real leader, and he was determined to pounce on it. He quickly called on al Hamiyyah - the Majlisi Guard, which had been his sole focus for much of the past few years. Cyrah had devoted those years to building this army from the ground-up, armed with the latest weaponry and drilled in the latest tactics, striving and bribing and threatening dozens of Majlisi viziers for more funds as he reformed every aspect of the military.

And this was the result. Only 24,000 men-at-arms, but this 24,000 had to be amongst the best trained armies in Iberia, if the sheer gold invested into them was any indication. Still, however, the Guard had not yet tasted true combat - so Ibn Cyrah quickly left the capital to join the army, setting off on a march northwards without delay. The Portuguese revolt would be their first test.

And they passed with flying colours. The rebels were mere peasants, to be sure, but the Majlisi Guard was able to quickly and efficiently break them just beneath the walls of Qulumriya, before proceeding into the city and capturing all the major towers and citadels. More importantly, the disciplined Guard refrained from sacking Qulumriya - a trap that many Andalusi armies historically fell into, and had led to the downfall of many a sultan.

Once the public executions were over and new governors were installed to rule the city, Ibn Cyrah left the Guard and began the trek back to Qadis, where diplomats had just arrived from Barshaluna.

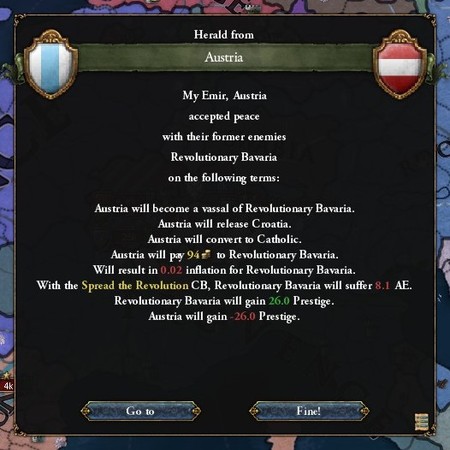

Apparently, the Emirate of Qattalun had been facing a wave of revolutionary fervour over the past few months. Starting in Corsica but quickly travelling across the Mediterranean and engulfing much of the country, these Radicals were undoubtedly inspired by the same ideals as the Bavarian Revolutionaries, who’d managed to seize and sack several cities in the archduchy over the past few weeks.

These Muslim Revolutionaries even had the nerve to march on Barshaluna itself - one of the largest and richest Iberian cities - though not before Qadisian diplomats managed to escape. Fortunately, however, the crisis didn’t escalate much further than that, with the Emir of Qattalun marching on the peasant rabble with a slightly smaller but far more disciplined force.

Once his continental holdings were secure, the Emir embarked from Barshaluna with the bulk of his army, crossing the Ligurian Sea and landing just off the northern coast of Corsica. There, he unleashed his men on the island, leaving them to murder, burn, rape, loot, plunder, reave, sack and pillage to their heart’s desire.

When the army departed the isle some days later, it was left a shadow of it’s former self. Unfortunately for the emir, the people of Corsica would not forget the ravaging they’d endured, determined to avenge their fallen by dragging him from his palaces and freeing his head from his body.

Back in Qadis, meanwhile, Ibn Cyrah was faced with another rapidly-escalating problem. Ever since the Majlisi Revolt, the merchants and traders of Al Andalus had been fleeing the peninsula en masse, fearing the fate that the Taifas had in store for them. Even those who’d been assured the mercy and protection of the Majlis refused to stay behind and help reforge Al Andalus, instead escaping across the straits into Morocco, or taking the first ship hailing for Ibriz, or even defecting and accepting exile in France or Provence.

This was a huge dilemma for the Majlis, as the League of Merchants had owned the vast majority of ships, goods, charters, permits and licenses that were valid in the many trading routes linking the old world and the new. So as they left Iberia, so did their trade, their contacts and their wealth.

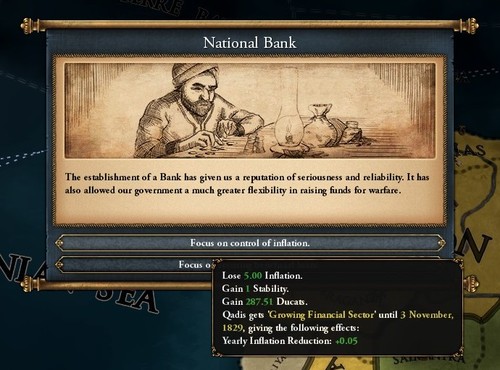

Needless to say, money was vital if the Majlis’ ambitions were to be realised, and they were quick to demand solutions, leaving Ibn Cyrah to do the only thing he could. He established a national bank.

Of course, financial institutions had always been present in one form or another, but the Andalusi Bank would be the first of a new species of institution that would quickly give rise to more modern forms of banking. The recentl bankruptcy of Al Andalus meant that the Majlis was no longer able to afford loans, but with the founding of a new central institution to take on most of the government’s debts, they could finally begin issuing money, bonds and notes once again.

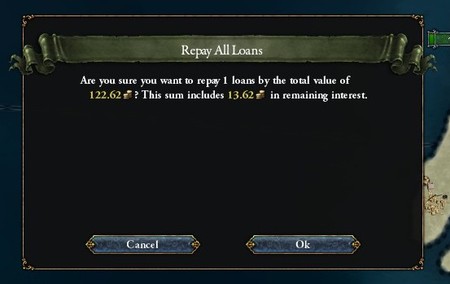

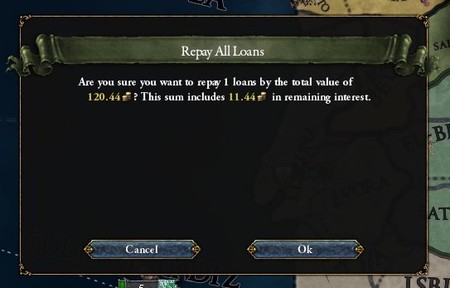

With money slowly trickling back into the economy, Ibn Cyrah began paying off the debts incurred during the Revolt and those sustained whilst rebuilding the army, quickly working towards making the Majlis solvent again.

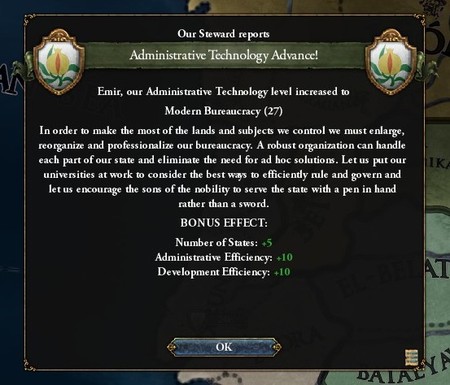

The Grand Vizier also began the work of reforming the bureaucracy of Al Andalus. Not only did Ibn Cyrah form a ‘closed council’ of his closest allies in the Majlis to help rule the state, but he also began assigning hefty duties to his own apprentices and assistants, many of whom didn’t have seats on the Majlis.

Ibn Cyrah did meet with some opposition in the assembly over this, of course, but it also meant that every aspect of ruling was now controlled by him and his loyalists.

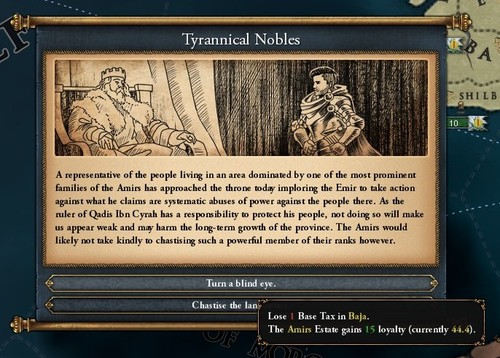

Well, almost every aspect. Ibn Cyrah still had his superiors - the old names of the Majlis, the powerful emirs who ruled over the vast swathes of land surrounding Qadis, and the men who were responsible for actually putting Cyrah on the throne.

He still owed his loyalties to them, and whilst they mostly left him to rule as he saw fit, Ibn Cyrah was forced to turn a blind eye to their constant transgressions and crimes. These nobles were able to rule their territories with impunity, taxing their peasants mercilessly, rooting out heretics and publicly executing them, and even raising small warbands to feud with one another. All of which was illegal, of course, but no one was going to stop them.

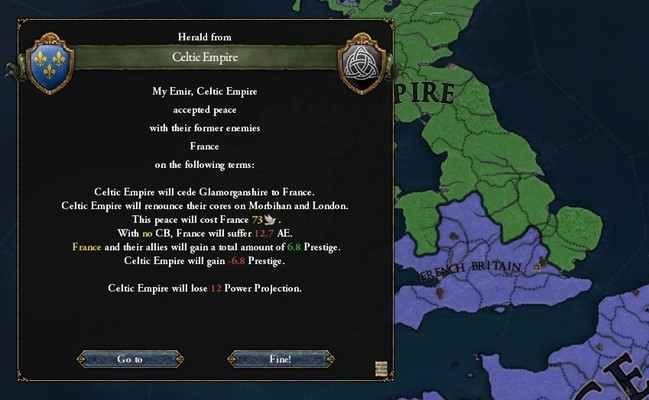

Meanwhile, further north another war broke out between France and the Celtic Empire as the High King in Dublin intervened in a colonial war declared by King Aton, with the Irish king Clemens probably hoping to recapture his rich English territories whilst the French were distracted by the tenacious Andeans.

This quickly proved to be another idiotic manoeuvre by the High King, as Aton and his navy quickly seized control of the Channel, sending thousands of Frenchmen flooding into Celtic England over the course of several weeks. Led by innovative commanders, drilled in novel tactics and armed with better artillery, the French quickly captured large parts of Wales and northern England, sacking countless towns and cities as they marched across the length of Britain.

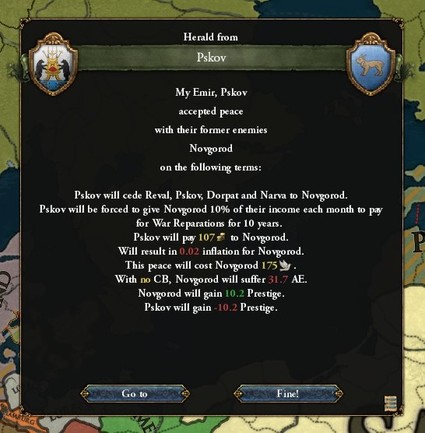

To the east, meanwhile, the continent-spanning juggernaut that was Novgorod was only growing larger and more powerful.

Led by the teenage Tsar Vasiliy V, a renewed era of prosperity was quickly spreading from the snow-capped cathedrals and palaces of Veliky Novgorod. The newly-reformed Russian armies were marching from one end of the empire to the next, intermittently warring with near every neighbour they bordered, from the Khalkha Khanate in Central Asia to the Principality of Pskov on the Baltic Sea.

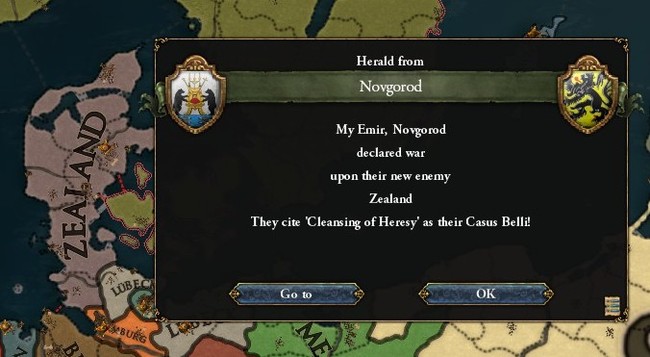

And Vasiliy’s ambitions weren’t limited to that, with the Tsar looking to involve himself further in European affairs. As revolutionaries rapidly tore the centuries-old Archduchy of Bavaria to shreds, Novgorod took the opportunity to declare on Zealand, a German duchy that ruled over large parts of Denmark.

This would be Vasiliy’s - and Novgorod’s - road to the riches of Germany. Maybe then he would look to Smolensk, and the formation of a true Russian Empire.

Moving back across the North Sea, the French armies managed to seize possession of virtually all major cities in Celtic-controlled Britain by 1778. And from a small port in Wales, King Aton masterminded a remarkable plan that saw the successful crossing of a small force across the Irish Sea, which quickly went on to launch a surprise attack on Dublin itself - a city that had not fallen to foes since the Medieval Era.

Needless to say, an attack from the relentlessly-patrolled Irish Sea had not been expected, and the city fell without putting up much of a fight.

The less said about the Burning of Dublin the better, but as the name implies, the capital of the Celtic Empire was not spared by the Frenchmen - with the High King actually captured and imprisoned by the attackers. But the royal palace was apparently still being plundered and ransacked as the king was being carted away, because in the midst of all the chaos, it seems a stray bullet went off and killed Clemens - ruler of a domain that stretched from East Anglia to Melanesia.

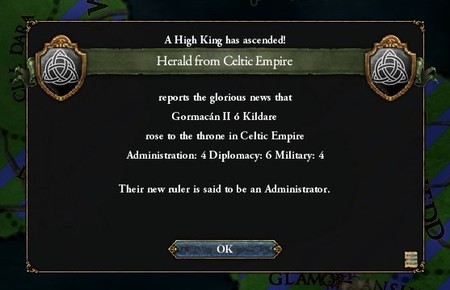

Clemens had still been young upon his death, and without any sons to inherit him, the Celtic Empire went to his uncle instead - one Gormacán ó Kildare, who happened to be at his Kilkenny estates at the time, and thus escaped the brutal sacking of Dublin.

For all his family’s misfortune, Gormacán had a good head on his shoulders, and reached out for peace negotiations immediately upon ascending the throne. King Aton is said to have met personally with the new High King, and after securing several favourable trade deals, he agreed to make peace on relatively lenient terms.

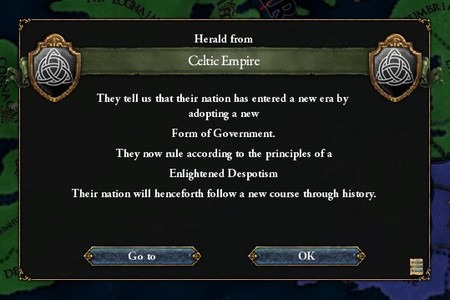

Once his shores and forests were safe, Gormacán called a council of his dukes and high ministers. With successive losses against Ibriz, Morocco and France, it was apparent now that the Celts were quickly falling behind on the world stage, and unless they did something to halt their fall they would likely end up in the same situation as Al Andalus - that is to say, nonexistent.

So, with the approval of his advisors, the new High King of Ireland, Scotland and England began a series of reforms aiming to bring the Celtic Empire back on par with their rivals (especially France), starting with the declaration of an Enlightened Despotism.

They were a constitutional monarchy before this, by the way, but I guess they saw how well that turns out.

Across the Channel, meanwhile, King Aton - though he now insisted on being called the Sun King - turned his attention back to Central Europe, where he had yet to figure out how to deal with the rapidly-spiralling crisis in Bavaria.

The Sun King eventually decided to send armed regiments into Germany; the Radicals had already defeated a number of Bavarian armies, but the French were a different matter altogether. And to add to that, he began forming a web of alliances with the states surrounding Bavaria, offering them protection against the threat of revolution.

And whilst his forces were still fighting what had quickly bogged down to a guerrilla war in the Incan Empire, King Aton also began making moves against France’s traditional rivals in Morocco, sending diplomats across the Atlantic and to the colony of Imjir, where a number of guarantees and promises were ironed out between the ruling Berber nobility and French agents.

This all flew above the head of Sultan Issam, who didn’t really care much for his Gharbian possessions, instead favouring his more valuable empire in India. He actually only just returned from a long but successful Indian war late in 1779, with huge celebrations and debaucheries greeting him in Marrakesh.

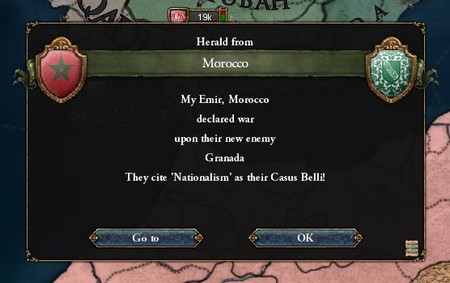

Issam didn’t much enjoy life at court, however, he was a warrior first and foremost. So leaving governors and regents to rule in his stead once again, he march north to Ceuta from his capital mere days later, from where he declared war by crossing the Straits of Gibraltar with an army.

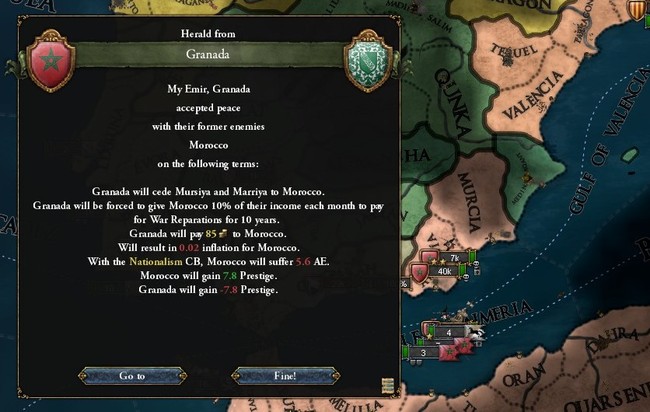

Not (yet) against Qadis and the Majlis, fortunately, he instead directed his forces for Granada - where the Mad Sultan was still residing - under the guise of quashing the persistent Shia heretics.

The Majlis knew that this went well beyond mere heresy, however. The Almoravids had always desired a foothold on Iberia, they had tried to establish one countless times already, and with the Taifas divided and feuding, Sultan Issam saw his best opportunity to finally achieve his forefathers’ ambitions.

Ibn Cyrah was immediately met with the angry railings of a hundred old men in the Majlis Assembly, all criticising and denouncing him for not going to war earlier. Spurred on by the real threat of being overthrown, the Grand Vizier decided to finally take the final step and actually declare war…

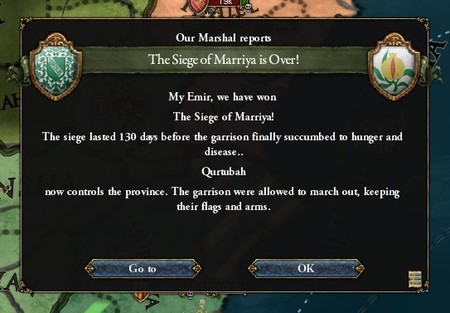

The Majlis unanimously approved his motion, of course, and the Majlisi Guard was on the march before the month was out. Ibn Cyrah left the capital to personally micromanage the war, pushing the Guard into a forced march as he did so, desperate to capture Jabal Tariq before Moroccan forces could.

And fortunately for him, the Berbers met with some trouble in the straits, giving the Majlisi Guard just enough time to defeat and replace the Jizrunid garrisons in Jabal Tariq. Sultan Issam was infuriated upon seeing Qadisian soldiers manning the fortresses, obviously, but he eventually decided against sparking another war.

Instead, he marched his forces northwards and towards Qurtubah - where the armies of Granada and Castille (their allies) were massing. The Mahdi, meanwhile, had not only declared a war of his own against Tulaytullah, but he’d also joined his Moroccan allies in their war against Granada, sending 20,000 Sunni fanatics to lay siege to a fortress in Almeria.

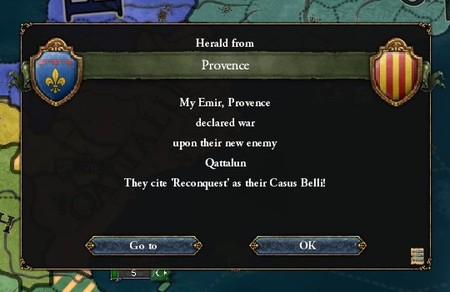

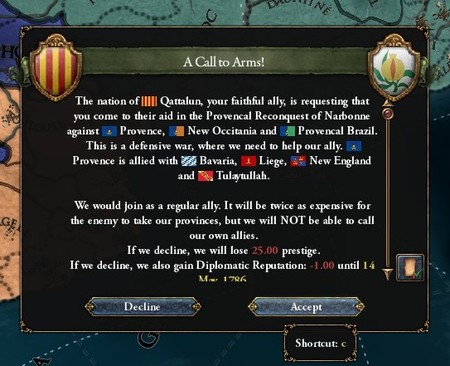

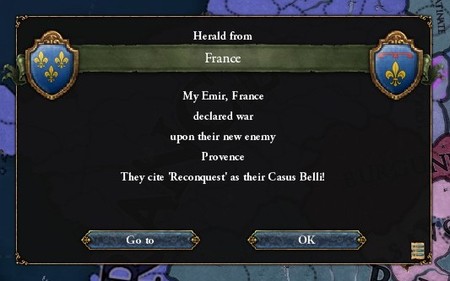

In the northeast, on the other hand, another war broke out with the Provencal invasion of Qattalun. The Emir of Barshaluna had joined the Majlis in its war against Granada, but with Occitan armies now pouring into northern Iberia, he was forced to march his men north again in defence of his territories.

He sent requests for aid to Qadis, of course, and this time the Majlis didn’t hesitate in accepting his call-to-arms. Granada still separated Qadis and Qattalun, however, so the Majlisi Guard wouldn’t be able to aid their allies until that war was over. Until then, Qattalun stood alone.

This. This had been what everyone was waiting for this past decade, and it had taken just one declaration to plunge the entire peninsula into war. Now the fates of each and every taifa hung in the balance, their survival or dissolution to be determined over the next few years.

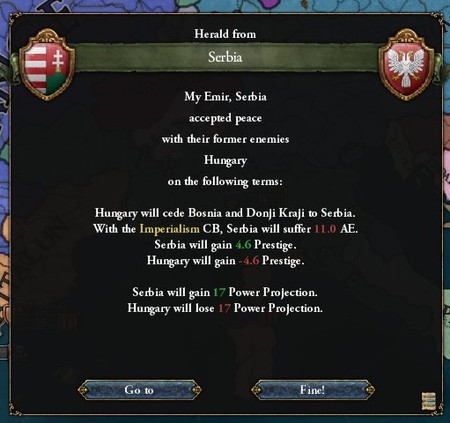

Iberia wasn’t the only peninsula engulfed by conflict, however, the Balkans were similarly drenched in blood as wars broke out between feuding principalities every few months. After decades of constant bloodshed, however, two large states managed to emerge from the chaotic mess of principalities and princedoms - Hungary and Serbia, only for another war to break out between the two kingdoms a few days into 1781.

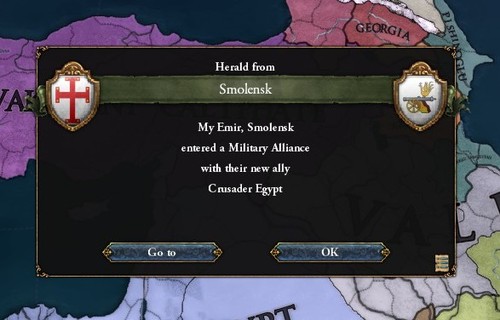

Further east, the king of Crusader Egypt managed to form an alliance with the tsar of Smolensk, in opposition to the declining Sunni Vakhtani Caliphate. The two monarchs met several times to draw up invasion strategies, planning to partition the Armenian empire and carve up their own spheres of influence.

This was going to be one of the biggest wars ever to sweep the Near East, but a scant few months before the invasion was to be launched, disease hit Alexandria and claimed tens of thousands of lives, including that of the Sahidic king.

His only son was still a mere child, and the widowed Queen-Regent was far more Christian that her husband had been, refusing to sanction war so long as she held the reigns of power.

The Caliph saw this as a lifeline, an opportunity to assert his own position, hoping to unify his disparate and unruly people by giving them a common enemy: the Latin Empire. Thousands of Armenians, Greeks and Arabs flooded into Thrace in the summer of 1781, looking to expand Muslim influence in the Balkans.

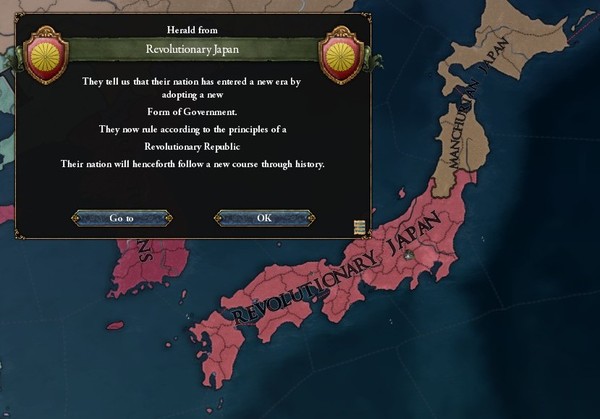

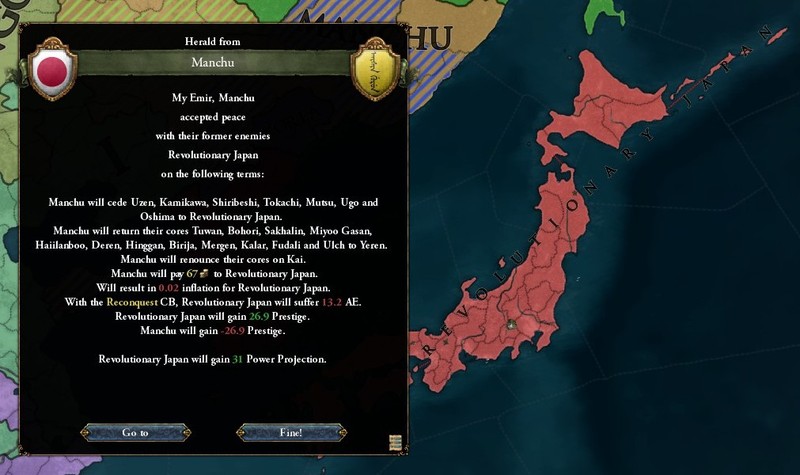

Halfway across the world, on the other hand, the people were rising up and deposing their traditional rulers. For a period of six years between 1776 and 1782, thousands of Manchu noblemen and their samurai puppets were executed in gruesome public ceremonies all across Japan, as the peasantry declared the end of a century of humiliating Manchu rule.

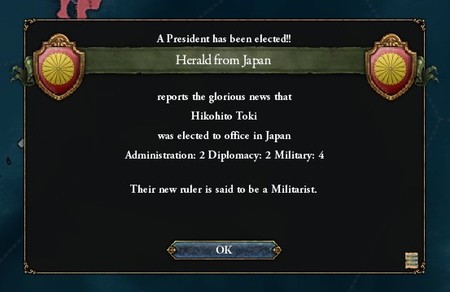

The Japanese quickly reclaimed large parts of their islands, expelling foreigners and heathens wherever they could be found. Once the historic Imperial capital of Kyoto was recaptured, their leader - one Hikohito Toki - proclaimed the dawn of a new era in Japan, an era of where noble and peasant no longer existed, an era where the common man ruled jointly, an era of republicanism.

And he would be their first Shushō - or grand premier.

And once his control within Revolutionary Japan was secure, Hikohito Toki turned northward again, looking to not only repel Manchu remnants on the home islands, but also establish republican footholds on the continent.

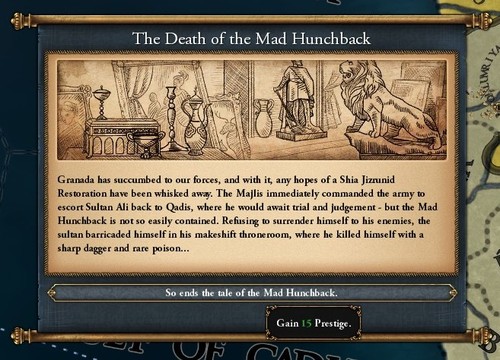

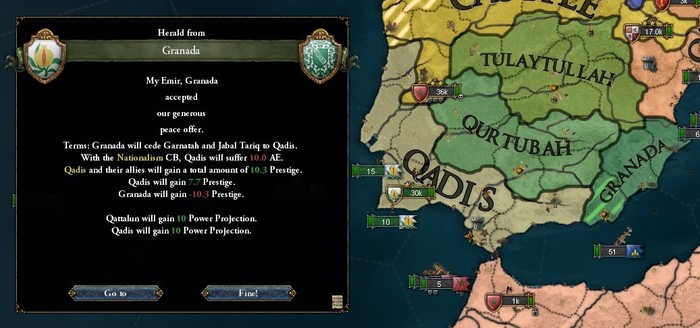

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, Ibn Cyrah had spent months trying to capture the fortress in Granada. The Mad Hunchback’s capital was large, well-fortified and well-stocked, however, and in the end the Majlis was forced to take out more loans and recruit thousands of mercenaries before being able to fully surround the city and force it to capitulate.

Once again, Ibn Cyrah forbade his army from sacking Granada - despite its sizeable Shia and Jizrunid-loyalist population. Instead, he rushed straight for the citadel at the centre of the city, where the Mad Hunchback would surely be waiting… Not prepared to surrender himself to his enemies, however, Sultan Ali III took his own life upon hearing of Granada’s fall, sliding a dagger between his ribs in the large and empty halls of the Alhambra. The last of the Jizrunid Sultans was dead.

Sultan Issam was still busy conducting land campaigns in the plains of Central Iberia, proving his genius on the battlefield time and time again. Not only did he manage to defeat the entire Castilian army a few miles north of Qurtubah, but the warrior-sultan was also able to throw them back in time to meet the forces of Granada (jointly led by the Mad Hunchback’s sons), which he was able to similarly crush in a few short hours of battle.

Unfortunately for Ibn Cyrah, however, whilst he was busy sieging Granada the Mahdi had been able to capture Almeria. And Qurtubah controlling the fortress meant that Morocco controlled the fortress, giving the Almoravid Sultan a potential foothold on the peninsula.

Looking on the bright side, it did mean that the Majlisi Guard was finally free to march through the entirety of Granada, allowing Ibn Cyrah to finally participate in a few battles against Provence and their allies.

As it turns out, however, there weren’t very many invaders actually in Qattalun. In fact, whilst marching towards Barshaluna, the Majlisi Guard met with only a few hundred Occitan soldiers here and there, looking like they’d only just escaped from a bloody battle with their lives and nothing else.

Upon reaching the Qattalun capital, however, the emir wasted no time in explaining what’d happened to Ibn Cyrah. According to him, Allah himself had intervened by persuading the infidel King Aton to declare war on Provence, with French armies sweeping into Occitania and Qattalun within weeks.

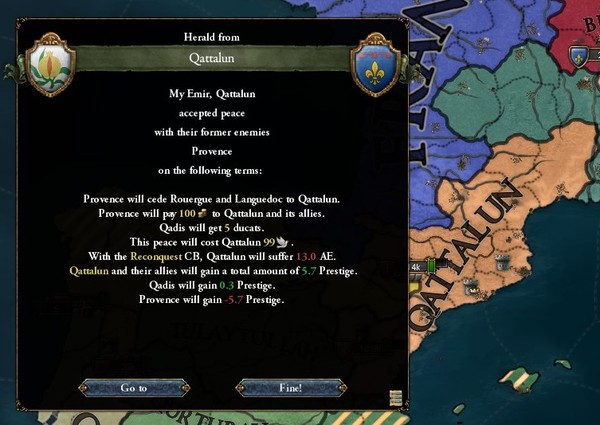

That had allowed the emir, who had avoided pitched battle until then, to quickly sweep into Christian Europe and capture large parts of eastern Occitania. Before long, the Qattaluni were breathing down on the city of Provence itself, and the King was forced to make peace on Muslim terms.

All good news, no doubt. This freed Ibn Cyrah to lead the Majlisi Guard back to Qadis, from where he marched them northwest, where his agents had reported the presence of another army of Granada. They had obviously not learnt from their loss against the Moroccans, but Ibn Cyrah was only too pleased to give his army more experience, as al-Hamiyyah swept aside the tired and war-weary forces of the Mad Hunchback without much difficulty.

Whilst Ibn Cyrah began rounding up thousands of prisoners near Qulumriya, another large battle broke out just outside Qurtubah, this time between the armies of Castille and the Mahdi. And with some help from his Almoravid allies, the Mahdi emerged triumphant once again, only adding to his exaggerated and downright heretical claims of being "chosen by Allah".

Back in Qadis, however, the treasury was beginning to suffer as the war dragged on. And with no end in sight for the conflict raging between Morocco, Qurtubah, Tulaytullah, Granada and Castille, Ibn Cyrah decided that it was time to bow out of the conflict.

So, with the approval of the Majlis, he quickly managed to reach a peace agreement with the Mad Hunchback’s sons. Simply put, Qadis retained control over everything that Ibn Cyrah and his Guard had captured, along with all property and possessions previously owned by the Jizrunids.

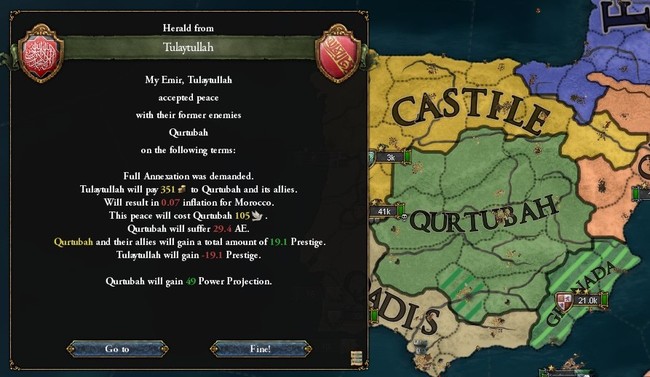

In the north, Qurtubah and the Mahdi were still embroiled in war against Granada, Tulaytullah and Castille. Ordinarily, no amount of divine help would’ve won the Mahdi his war, but he had the Almoravids as his allies - they alone could sweep across the entirety of Iberia without much trouble.

Indeed, Sultan Issam led some 45,000 Berbers on a spring campaign across the width of Castille, starting with the capture of Beira and ending with the sack of Burgos. A few hundred miles away, another 10,000 Berbers supplanted the Mahdist Army as the fanatics surrounded and breached the walls of Tulaytullah, quickly pouring into the city and setting it afire.

The self-styled Sultan Abd-al-Qays actually put down his arms and surrendered after the walls of Tulaytullah were breached, but the Mahdi wouldn’t let him get away so easily. After personally presiding over a short trial, the Mahdi sentenced the Jizrunid claimant to death by breaking wheel, a particularly painful and gruesome way to die.

Ever since its conquest, Tulaytullah had been both praised and vilified as the City of Sultans, a constant Jizrunid stronghold and loyalist hotbed. By the end of the Sack of Tulaytullah, however, it would be transformed - as any and everyone who was suspected of having Jizrunid allegiances (or anyone other than the Mahdi, for that matter) was brutally murdered, beaten in the streets, stabbed in their beds, strangled whilst bathing and cut down whilst praying.

And by the end of the month, the entirety of Jizrunid domains in the north were captured and absorbed by Qurtubah, with every city, castle and town given the same treatment. This kingdom of fanatics wasn’t simply limited to Qurtubah anymore, with the Christians in the north and Muslims in the south all coming to call it the "Mahdiyyah", or the Regime of the Mahdi.

With his allies successful in the north, Sultan Issam also concluded peace in Iberia, demanding a stretch of land along the eastern coast. And with that, an ambition stretching back to the Medieval Era is fulfilled as the Almoravids establish a foothold on Iberia.

And this is undoubtedly just the beginning of Issam’s plans for the peninsula, with the young sultan already drawing up plans for further invasions. This may very well be the the end of any hopes for a unified, independent al-Andalus.

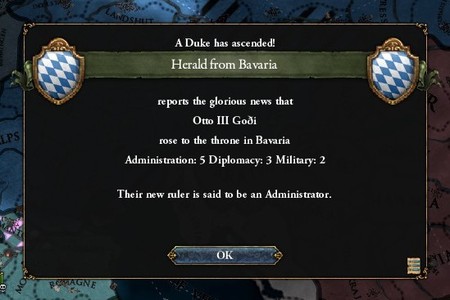

Shifting focus to Central Europe, meanwhile, dramatic changes are set off by the ascension of Otto III to the Archduchy of Bavaria. A clever and capable young man, the new archduke is determined to stave back the recent advance of the Revolution and reconquer his rightful inheritance, at any costs necessary.

That will be difficult, to say the least. For obvious reasons, the youngster wasn’t crowned in the traditional Munchen coronation, instead proclaimed Archduke in an elaborate ceremony in Franconia. And whilst being a duke-in-exile is no pleasantry, it did give Otto the opportunity to form alliances and pacts with his neighbours, convincing them that his cause was one with theirs, and that the Radicals would undoubtedly look to export their madness once their hold on Bavaria was secure.

Thus, by the time he’d reached adulthood, Otto had managed to piece together a conglomerate army of Bavarians, Franconians, Occitans and Dutchmen. And mere days after his sixteenth birthday, the Archduke led this monarchist army into his homeland, intent on crushing the Revolution once and for all.

To his utter shock, however, there were huge revolutionary armies lying in wait for him to do exactly that. Hundreds of thousands, they were in the north and the south, in the east and the west, marching across the country and back as they captured any nobles they could get their hands on, subjecting them to mock trials and murdering them by a variety of public executions.

All the same, Archduke Otto pushed southward and met with them, knowing full well this would be his only chance to take back what was rightfully his. Their commanders and tactics weren’t particularly revolutionary, but the sheer numbers would prove too much for Otto to overcome, as his unified Bavarian-Provencal-Franconian-Liegan force collapsed before the Revolutionary onslaught.

And to his great detriment, young Otto was knocked off his horse in the midst of all the fighting, found unconscious in the mud hours after the battle had ended. He immediately demanded to be ransomed, but the revolutionaries had been trying to get their hands on the Archduke for a decade now, and weren’t going to give him up for mere gold.

In fact, they weren’t going to give him up for anything at all. They were going to use him, as his kind had done for thousands of years, to send a message - albeit more mercifully.

The death of Otto, last Archduke of Bavaria, would come on a cold February morning in 1785. The scruffy youngster was violently dragged from his cell, his screaming no use as he was forced onto a raised platform on München’s busiest street, where a newly-designed contraption awaited him. His head was secured at the bottom of a large frame, from which a suspended blade fell down with frightening speed, slicing through the cords and muscle of his neck in a single clean strike.

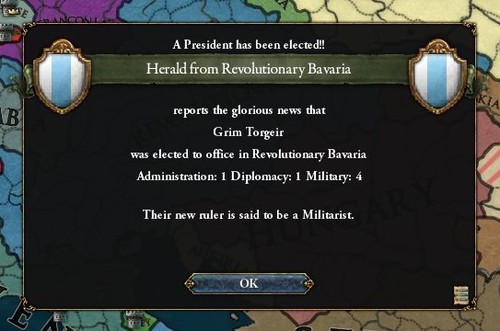

The Archduke’s screams were abruptly cut off, and a huge roar of triumph swept through the gathered crowds. One of the leading generals of the Revolutionary forces, who apparently went by the name Grim Torgeir, chose this moment to declare the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the formation of the German Republic, led by an elected National Assembly that was to be based on the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Central Europe, upon the outbreak of the German Revolution.

In reality, this would spark the beginning of a decade-long period of utter chaos, as the elected government failed to assert control over the country and the enraged peasantry rioted and rampaged not only across Bavaria, but across all Germany.

Grim Torgeir, however, had left München within days. He had stated his ambitions after the Archduke’s execution - to unite Germany under republicanism - and that did not extend to the messy politics of München. Instead, he rushed to join his armies on the border, where he launched the first of many campaigns against the small German principalities surrounding Bavaria.

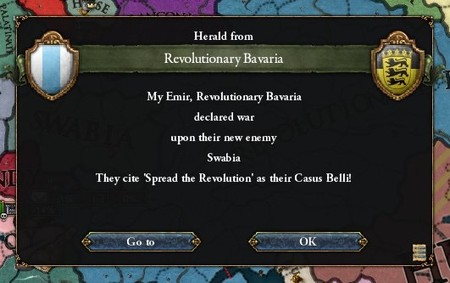

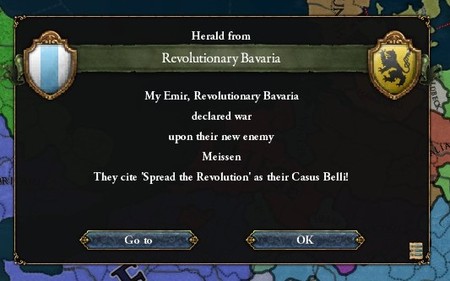

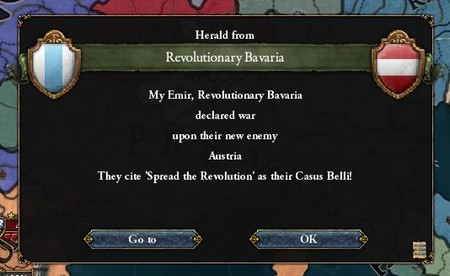

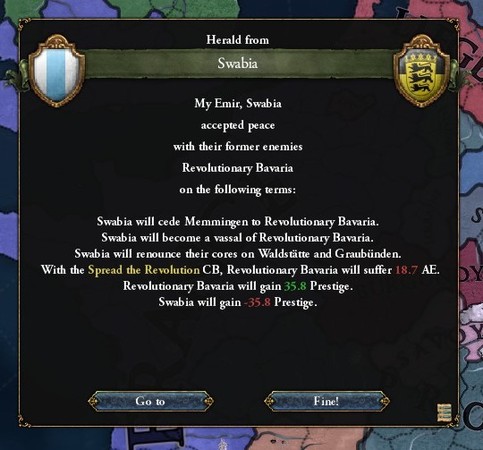

And through grim tactics and sheer numbers, these early wars were over within mere weeks, with the revolutionaries quickly storming fortresses and capturing cities, where they executed countless dukes, aristocrats, patricians and minor noblemen with the same device that had killed their Archduke. Temporary puppet republics were formed in Swabia, Austria and Meissen, as Grim Torgeir quickly shifted from one target to the next.

The revolution would be brought to the rest of Germany and beyond, by force if necessary, he was sure of it.

Across the width of the world, meanwhile, the Japanese Revolutionaries finally managed to end their war in victory. The Manchu were expelled from Japan, and the shushō could begin to look further afield - to Manchuria, to Korea, and to China.

It would take time before the republic was ready to export the revolution, however - first it had been enforced within Japan. Hikohito Toki did begin planning for the future by forcing the khanate of Yeren to submit to Japan, however, likely hoping to use it as a launching point for invasions into Manchuria.

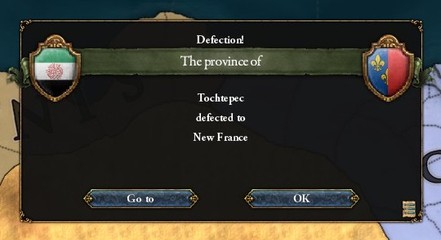

At the same time, across the vast waters of the Pacific, the Sultanate of Ibriz was beginning to spiral down a rebel hellhole of their own. Making the same mistakes as Al Andalus and Bavaria both, the Hishami Sultans had taken out huge loans to facilitate their wars against Iberia, France and the Celtic Empire, compensating by harshly taxing the peasants.

This would obviously prove to be a dire mistake, as Andalusi-Mayan Revolutionaries rose in revolt all across Central Gharbia. They’d manage to capture the entirety of the Yucatan peninsula before the year was out, and began pushing northwards before much longer, towards the Ibrizi capital and the court of the Hishamis.

And with the Revolutionaries now dividing Ibriz in two, the Sultan wasn’t able to march or transport his soldiers to suppress revolts in the south, resulting in much of his recently-conquered land breaking away once more. It would seem all the loans, all the difficulties and all the victories that the Hishami had worked so hard for would prove to be pointless.

And it didn’t end there.

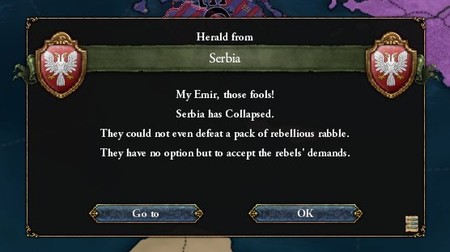

Back in Europe, the kingdom of Serbia had managed to see out their war against Hungary with a series of victorious battles, brokering a favourable peace treaty early in 1786. Whilst Serbian forces had been marching through eastern Hungary, however, separatists, royalists, particularists, revolutionaries and every other manner of rebel had taken the opportunity to rise up in revolt.

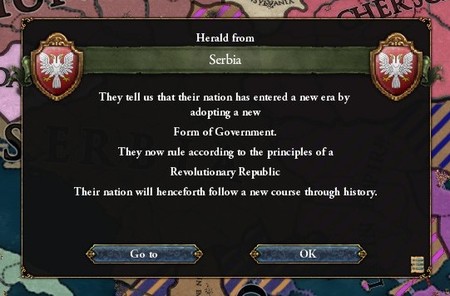

This ended with the capture of Belgrade late in the year by Serbian Revolutionaries, who had suffered the same toils and struggles as peasants all across Europe. The king and his immediate family was captured and imprisoned, with the Serbian Revolutionary Republic declared a few days later.

And once the revolutionaries had asserted their authority in Serbia itself, they wasted no time in looking beyond their borders and to the traditional prizes of all Balkan empires - to the cities of Athens and Constantinople.

From Asia to Europe to Gharbia, the world is aflame with the fires of war and revolution, fires that will revive the poor and oppressed, fires that will spare no king or nation, fires that will consume all in its path before being burning out. The end of the eighteenth century is drawing ever closer, and with it a simple question steadily approaches: what will the world look like at the turn of the century?